In the late 1920s, the Arrernte families of Ntaria (later established as the Lutheran mission of Hermannsburg) in the Northern Territory lost an estimated 85 per cent of their children to scurvy and malnutrition, brought on by severe drought.[1]See ‘Finke River Mission, Hermannsburg’, Dawn: A Magazine for the Aboriginal People of N.S.W., vol. 10, no. 8, August 1961, p. 9, available at <https://aiatsis.gov.au/sites/default/files/docs/digitised_collections/dawn/august_1961.pdf>, accessed 17 October 2017. Stricken with grief after having lost a daughter,[2]Andrew Mackenzie, ‘The Artists: Albert Namatjira – a Biographical Outline’, In the Artist’s Footsteps, 2000, <https://www.artistsfootsteps.com/html/Namatjira_biography.htm>, accessed 18 October 2017. young father Albert Namatjira – only in his twenties – then resolved to use whatever he had been given to improve the lot of his community, so long as it brought in the money.

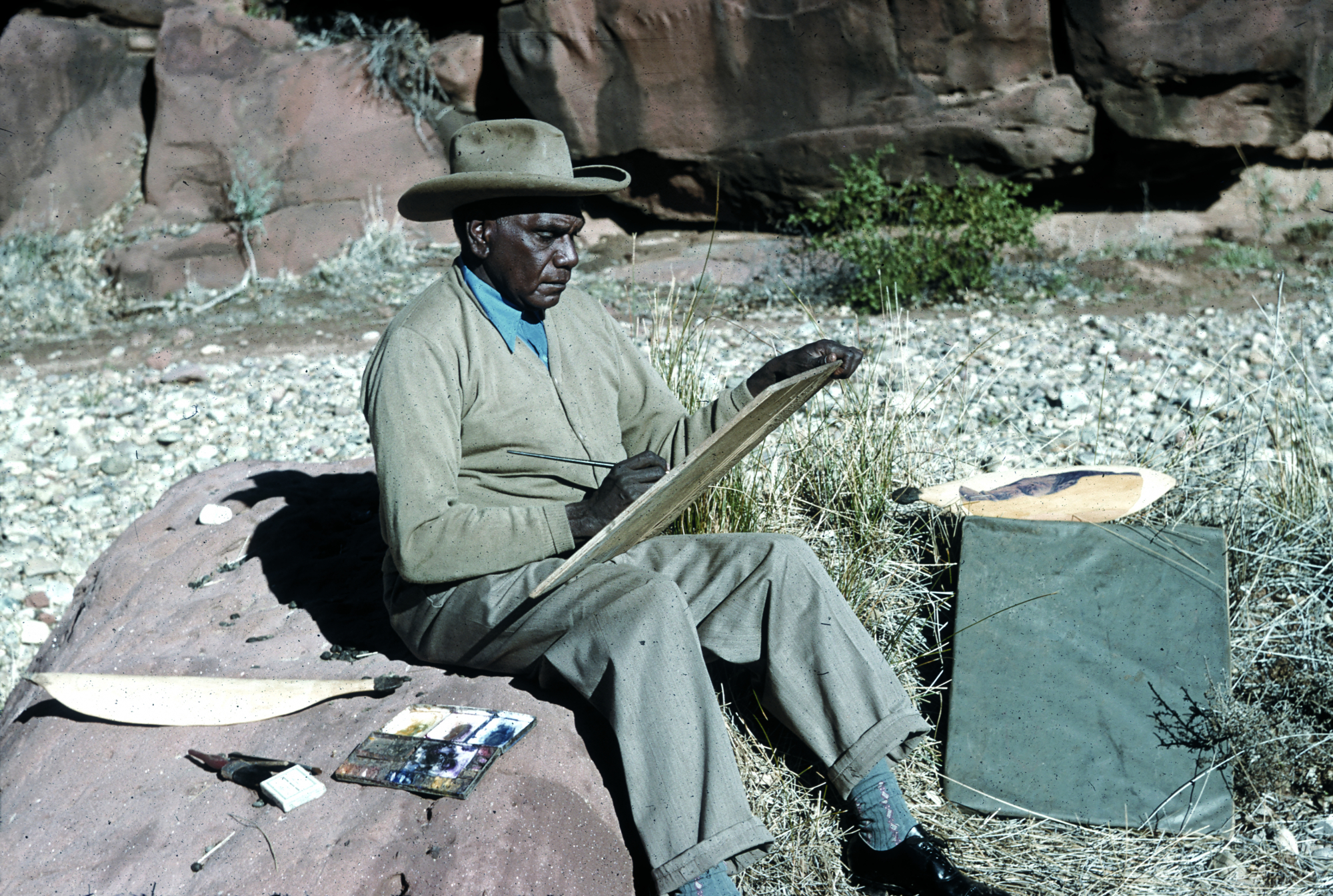

When the white artist Rex Battarbee, accompanied by colleague John Gardner, drove a converted Ford Model T on unsealed roads from Melbourne to Arrernte country in 1934, Namatjira found his opportunity. Battarbee and Gardner had come all this way once before – an utterly mad distance at the time – to paint watercolours of the desert’s interior and take them back to their coastal-dwelling urban audience. While in Hermannsburg in 1934, they exhibited their creations to the Arrernte locals. Namatjira saw their work and must have been deeply inspired, so much so that he might have asked himself the logical question: if a foreigner could paint his country and get money for it, why couldn’t he? This was the first significant time the connection between non-Indigenous artists and an Aboriginal genius would lead to an explosion in modern Australian consciousness – the first time an Aboriginal Australian would appropriate a European artform as a way to gain economic empowerment and, in doing so, fundamentally open non-Indigenous eyes to the forms and colours of this country. The Papunya Tula artist cooperative and the wider Western Desert painting movement would follow.

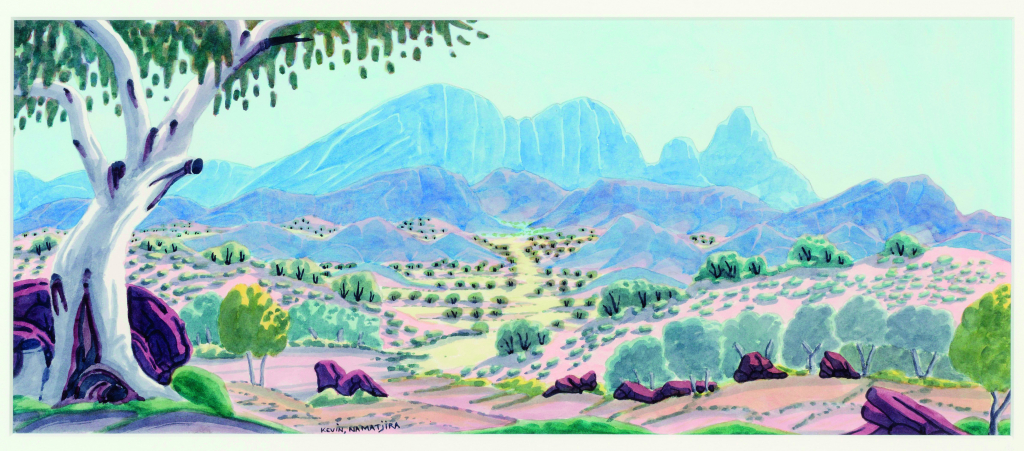

So Namatjira set to work painting his country, creating more than one hundred paintings a year.[3]A figure cited in Davies’ documentary. With Battarbee’s instruction, encouragement and promotion in Melbourne, his paintings soon made a cultural impact on white Australia that may well have no comparison in this nation’s modern history. Art depicting MacDonnell Ranges ghost gums hanging in a 1950s middle-class Melbourne living room may seem clichéd today, but the image betrayed something far more profound about what was then a still-embryonic national culture. In a typically Australian, straightforward and domestic way, a popular trend that could have easily been mistaken for cultural appropriation actually carried the weight of transformative cultural significance. A country and a consciousness that Europeans had desperately resisted in their imported buildings and gardens now, however subtly, adorned their walls.

This wasn’t intellectual painting – not in the modernist sense, at least. And not surprisingly, academic critics at the time had neither the sensitivity nor the feeling for Central Australian nature to appreciate and understand Namatjira’s work. But a great number of people did, to the extent that Namatjira became the first Aboriginal Australian celebrity; the first Australian citizen of Aboriginal descent; a recipient of the Queen’s Coronation Medal; the first Aboriginal Australian to meet the Queen, at Her Majesty’s request; and, with all this, the first Aboriginal Australian to significantly reflect this nation’s injustices back onto the popular consciousness. Tragically, it was Namatjira’s appalling legal distinction – as an Australian citizen, with rights not shared by his own family – that would bring on his destruction. Namatjira died in 1959, after having been sentenced to prison (spent at the Papunya Native Reserve) for supplying another Aboriginal person with liquor; the eulogy read upon his death pronounced: ‘In spite of many honest attempts to make him happy and a valuable member of our society, we have fundamentally failed.’

The non-Indigenous art world may now prize the surname ‘Namatjira’, attributing to it some heroic, commercially valuable individuality; for the artist’s own community, however, the living value of Namatjira’s heritage is the culture that has sprung out of his work.

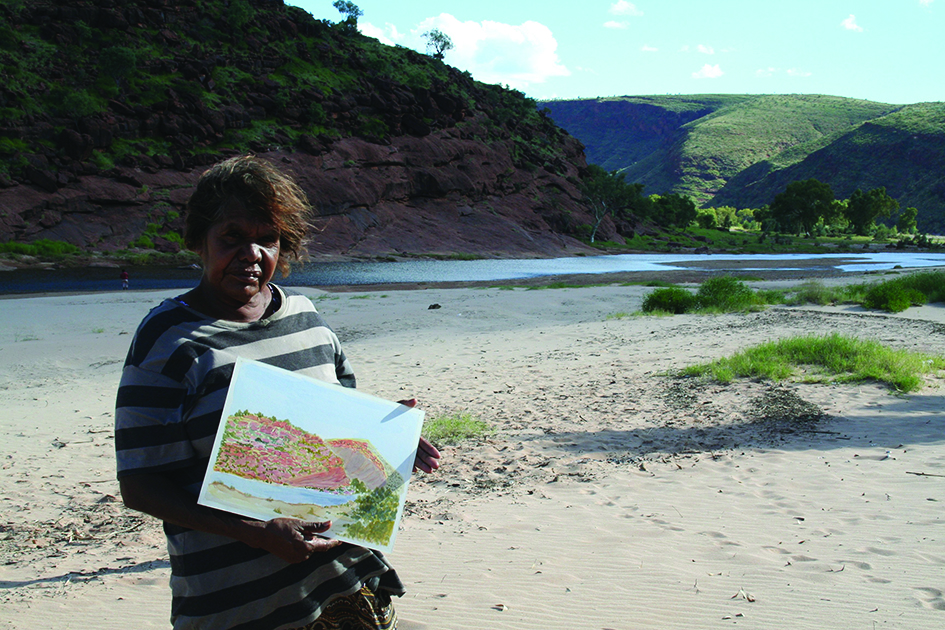

Namatjira Project (Sera Davies, 2017) is a documentary about the famed painter’s life – and a very admirable one at that. Constructed out of three intertwining strands, the film successfully achieves a woven narrative quality, threading its convergent stories into one by linking the specifics of Namatjira’s life and work to much bigger social and cultural challenges. One strand uses remarkable archival footage to chart his biography: his life in Ntaria, his meeting with Battarbee, his remote experiences of urban success, his celebrity, his tragedy. Another strand introduces us to the lives of Namatjira’s family, particularly his grandchildren Kevin and Lenie. We see Ntaria today. We learn of the financial difficulties the community has suffered from losing the copyright to Namatjira’s work (in 1983, public trustee John Flynn, without consulting the artist’s kin,[4]‘Albert Namatjira’s Family Recover Copyright of His Work’, SBS News, 15 October 2017, <http://www.sbs.com.au/news/article/2017/10/15/albert-namatjiras-family-recover-copyright-his-work>, accessed 17 October 2017. sold the copyright for A$8500, mistakenly assuming the new lease would run only seven years rather than the actual fifty[5]Daniel Browning, ‘“It Was a Mistake”: Public Trustee Who Sold Albert Namatjira’s Copyright’, ABC News, 10 March 2017, <http://www.abc.net.au/news/2017-03-09/albert-namatjira-copyright-sale-a-mistake/8335624>, accessed 17 October 2017. ). We follow the Namatjira family’s attempts to reclaim that copyright from the current lease holder, Legend Press; their trip to Sydney, then London; their surprise meeting with the Queen; their housing dilemma; and their expectations that someone in charge of all this, surely, will want and be able to help them.

The third strand follows the genesis, rehearsals and performances of the stage play Namatjira, developed by director Scott Rankin and distinguished Anangu actor Trevor Jamieson. This could so easily have been a clunky inclusion in the documentary, distracting from its essential focus on the titular figure and his legacy. But there’s a genuine reciprocity here between the contemporaneous creation of the play and the birth of the film. Thanks to the vulnerability of Rankin and Jamieson’s creative process, the stage production becomes less of a cultural product and more like another personality, following in the tracks of Namatjira’s own life and family. (Rankin describes the play as an ‘invitation’, and the gesture it offers in this film is very much in that vein, opening out rather than closing in on the artist and his cultural resonance.) Following successful Sydney shows, the production travels to Ntaria to perform the story for Namatjira’s community, though it is only after long conversations about the play’s representation of their ancestor – not least by an Anangu man – that Arrernte community elders agree to the performance. From there, members of Namatjira’s family and community accompany the production all the way to the UK, where, like their forefather, they are invited to meet Her Royal Highness (or the ‘Old Lady’, as Lenie calls her).

These strands in the film, edited together masterfully, project the significance of Namatjira’s individual life and work onto a vaster social and cultural canvas. Indeed, more than being just a biography of a great man, Namatjira Project examines the artist’s story and accomplishments primarily through the lens of how they reflect his community and its relationship to country. (Kevin explains, at one point, that his grandfather is long gone, dead – as if to clarify something we may not fully understand.) The non-Indigenous art world may now prize the surname ‘Namatjira’, attributing to it some heroic, commercially valuable individuality; for the artist’s own community, however, the living value of Namatjira’s heritage is the culture that has sprung out of his work. His art hangs on museum walls, but it also lives in the work of his children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren, as well as in the vibrant visual-arts movement known as the Hermannsburg School.

All of these narrative threads link the documentary to something bigger still. Begun in 2009 and run by arts and social-change organisation Big hART, the broader Namatjira Project has been described as:

a multilayered, long-term arts project that is many things to many people. It includes a creative community development project, an original theatrical work, watercolour exhibition and a documentary film.[6]‘Welcome to the Namatjira Project’, Big hART website, archival copy available at <https://web.archive.org/web/20160331222102/www.namatjira.bighart.org/>, accessed 26 October 2017.

Namatjira Project exposes the stark injustice at the foundation of our modern nation. Something that belonged to one family was taken – without consent – by another, infinitely bigger, more powerful and impersonal family.

The ‘project’, in other words, is not a singular production or number of productions as such, but rather a family- and community-based set of incentives. The Namatjira stage play is itself a part of this multifaceted endeavour, which has also led to the development of the Namatjira Legacy Trust, a fundraising body that aims to ‘secure positive futures’[7]‘What Is the Trust?’, Namatjira Legacy Trust website, <https://www.namatjiratrust.org>, accessed 17 October 2017. for the community, including the reclamation of the artist’s copyright from Legend Press.[8]Ron Cerabona, ‘Namatjira Legacy Trust Is Launched to Honour the Memory of a Great Artist’, Brisbane Times, 4 March 2017, <https://www.brisbanetimes.com.au/national/act/namatjira-legacy-trust-is-launched-to-honour-the-memory-of-a-great-artist-20170227-gum16m.html>, accessed 17 October 2017.

The Namatjira Project documentary is, thus, unashamedly a mouthpiece for an organisation and a particular agenda – something that was especially evident at the 2017 Melbourne International Film Festival premiere, at the conclusion of which envelopes were handed out for donations to the trust. So how do we negotiate all of this in terms of our appreciation of the film itself? Regardless of the motivations of Big hART (which are no doubt admirable), it’s an important question to ask. And perhaps the most immediate and obvious answer is: like the best activist cultural works, the film is not concerned primarily with promoting an all-encompassing, magic-bullet solution regarding Indigenous Australia. Instead, its motivation is local, concerned foremost with the Namatjira family and their community in Ntaria. The problems the film raises may be ubiquitous in Australia, but the solutions sought are specific to Ntaria – and hopefully secured with the real-world involvement of Namatjira Project’s viewers, whether through financial donations or in some other way.

Fortunately, even when the film is experienced without recourse to its activist objectives, what we have in Namatjira Project is a fine, enlightening work that can be appreciated on its own terms – for both the accomplishment of its story-telling and its emotional power. As stated, the documentary’s construction is profoundly effective; it is indeed very heartening to find a community-driven film so well made, so intelligently directed and pieced together. One must also note the astonishing intimacy the camera establishes with members of the Namatjira family. Their openness and forthrightness are not to be taken for granted; it takes a long time to establish that level of genuine trust. The most powerful example of that trust comes from the extremely shy, reserved Kevin, who gradually becomes the central voice in the film. In all really successful works, at some point the various elements begin to flow into one another and rise to a bigger, deeper meaning. This meaning gushes forth when Kevin, nervously waiting in London to meet the Queen, is asked what he’d like to talk with her about; he replies, ‘I’d like she could help me get land.’

Ultimately, this is the level of meaning this film reaches: in establishing a deep and trusting relationship with a particular (and, in this case, famous) family, Namatjira Project exposes the stark injustice at the foundation of our modern nation. Something that belonged to one family was taken – without consent – by another, infinitely bigger, more powerful and impersonal family. Though it would be incorrect to suggest that the film can be boiled down to a simple polemic on that injustice, in representing its subjects and their stories, the essential picture the film offers can hardly be more pointed in its political implications. The story of Namatjira’s legacy is entirely and disgracefully lodged in the history of dispossession. Almost sixty years after the artist’s death, the shameful gap between his prestige and the impoverishment of his people remains entrenched. Non-Indigenous dealers are profiting from his creations while his family and community remain in poverty. Government representatives are ready to enjoy the prestige that Namatjira’s work brings to the nation, but are unwilling to commit to real economic reform for remote Australia.

In short, the fundamental motivation underpinning Namatjira’s work – economic empowerment for his and other remote communities – remains not only unachieved, but also, in many cases, consciously impeded by non-Indigenous interests. The long-awaited return of the artist’s copyright to his estate[9]‘Albert Namatjira’s Family Recover Copyright of His Work’, op. cit. may be a step in the direction of making amends, but whether it heralds further, larger-scale redress is uncertain. What Namatjira Project offers us is the facts that, by virtue of Aboriginal Australians’ continued marginalisation, demand to be actively communicated by the filmmakers as a heartfelt political message.

https://www.namatjiradocumentary.org/

https://clickv.ie/w/metro/namatijira-project

Endnotes

| 1 | See ‘Finke River Mission, Hermannsburg’, Dawn: A Magazine for the Aboriginal People of N.S.W., vol. 10, no. 8, August 1961, p. 9, available at <https://aiatsis.gov.au/sites/default/files/docs/digitised_collections/dawn/august_1961.pdf>, accessed 17 October 2017. |

|---|---|

| 2 | Andrew Mackenzie, ‘The Artists: Albert Namatjira – a Biographical Outline’, In the Artist’s Footsteps, 2000, <https://www.artistsfootsteps.com/html/Namatjira_biography.htm>, accessed 18 October 2017. |

| 3 | A figure cited in Davies’ documentary. |

| 4 | ‘Albert Namatjira’s Family Recover Copyright of His Work’, SBS News, 15 October 2017, <http://www.sbs.com.au/news/article/2017/10/15/albert-namatjiras-family-recover-copyright-his-work>, accessed 17 October 2017. |

| 5 | Daniel Browning, ‘“It Was a Mistake”: Public Trustee Who Sold Albert Namatjira’s Copyright’, ABC News, 10 March 2017, <http://www.abc.net.au/news/2017-03-09/albert-namatjira-copyright-sale-a-mistake/8335624>, accessed 17 October 2017. |

| 6 | ‘Welcome to the Namatjira Project’, Big hART website, archival copy available at <https://web.archive.org/web/20160331222102/www.namatjira.bighart.org/>, accessed 26 October 2017. |

| 7 | ‘What Is the Trust?’, Namatjira Legacy Trust website, <https://www.namatjiratrust.org>, accessed 17 October 2017. |

| 8 | Ron Cerabona, ‘Namatjira Legacy Trust Is Launched to Honour the Memory of a Great Artist’, Brisbane Times, 4 March 2017, <https://www.brisbanetimes.com.au/national/act/namatjira-legacy-trust-is-launched-to-honour-the-memory-of-a-great-artist-20170227-gum16m.html>, accessed 17 October 2017. |

| 9 | ‘Albert Namatjira’s Family Recover Copyright of His Work’, op. cit. |