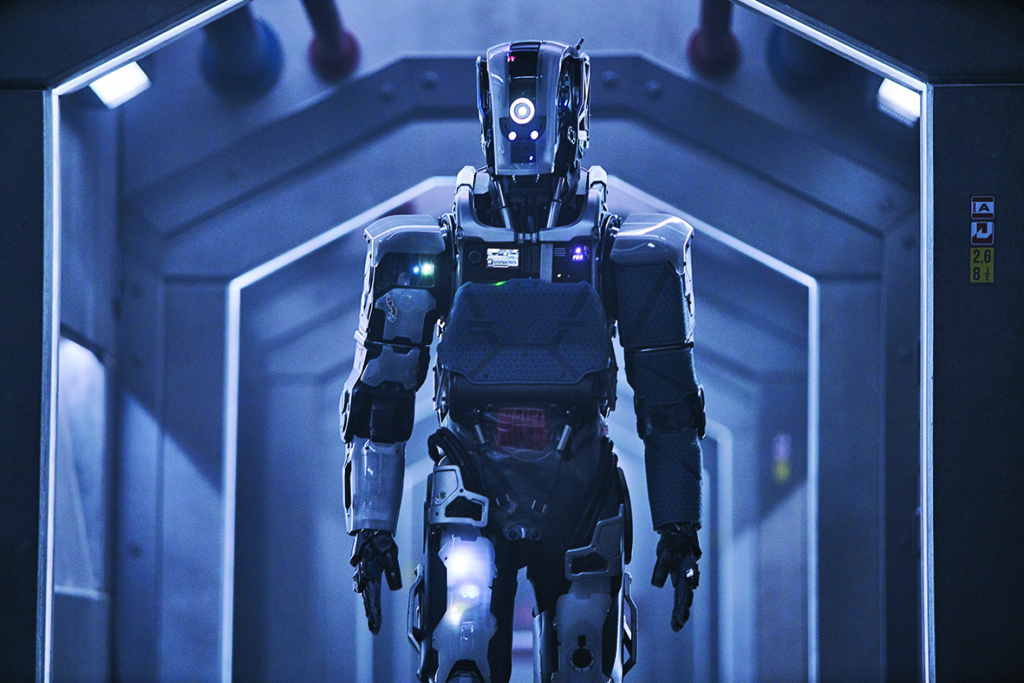

Let’s get this out of the way early: I Am Mother (Grant Sputore, 2019) isn’t an especially original movie. To a degree, that goes part and parcel with its chosen genre, speculative sci-fi, given the long shadow cast by its predecessors over the last half-century or so. Taking place in the wake of an ‘extinction event’, the film opens in a sterile, secluded bunker resembling a spaceship. From this setting alone, you’d be hard-pressed not to think of the long-running Alien franchise, whether you’re noting the similarities between the seemingly benevolent droid Mother (performed by Luke Hawker, voiced by Rose Byrne) and Nostromo’s MU/TH/UR 6000 in Alien (Ridley Scott, 1979), or observing that the 63,000 human embryos in Mother’s care recall the setting of the franchise’s most recent instalment, Alien: Covenant (Scott, 2017).

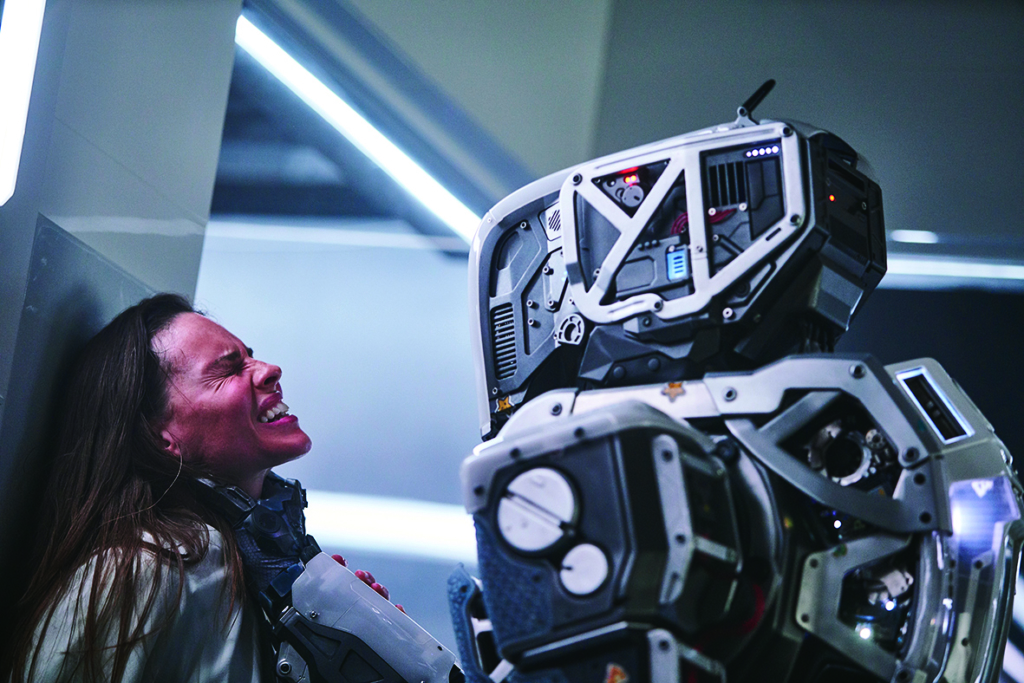

But it’s not like Scott has a monopoly on these elements. As Daughter (played by Clara Rugaard as a teenager), Mother’s human ward, grows up and begins to doubt her mechanised guardian’s intentions, your mind might instead go to GERTY (voiced by Kevin Spacey) from Moon (Duncan Jones, 2009) or HAL 9000 (voiced by Douglas Rain) from 2001: A Space Odyssey (Stanley Kubrick, 1968). When it becomes clear that Mother’s benevolence is not what it seems to be – as prompted by the arrival of an unnamed outsider (Hilary Swank, credited only as ‘Woman’) – audiences would be forgiven for drawing connections to either The Terminator (James Cameron, 1984) or even 10 Cloverfield Lane (Dan Trachtenberg, 2016), the latter another tale of a dubious protector set after an ambiguous apocalyptic event. Or, really, to any one of the myriad movies made about malevolent machines.

I could go on, but I’ll stop the laundry list of references there; I don’t intend to fall into the trap that has snared many a critic of characterising genre films solely in terms of their precursors. And, thankfully, Sputore (who co-conceived the story with Michael Lloyd Green) makes no attempt to shy away from admitting the familiar facets of the film. Discussing I Am Mother’s influences, he told Film School Rejects in June, ‘I only knew how to make this film because I’d watched so many different movies beforehand, and it is a reflection of the diet of movies that I grew up watching,’ going on to detail his debt to films like Alien, Moon and Terminator 2: Judgment Day (Cameron, 1991).[1]Grant Sputore, quoted in Brad Gullickson, ‘Talking Love and Robots with the Director of I Am Mother’, Film School Rejects, 15 June 2019, <https://filmschoolrejects.com/i-am-mother-director/>, accessed 11 October 2019.

Yet Sputore was also quick to downplay the impact of such progenitors on his creation: ‘I’m mindful of [these influences …] but there’s not really one singular film or a handful of films that [I Am Mother] most closely approximates or is inspired by.’[2]ibid. While originality tends to be prized in critical conversation, there’s nothing to say that a film – especially a genre film! – wearing its influences on its sleeve is inherently a bad thing. Plenty of good films interrogate, recontextualise or simply execute genre tropes with enough panache to excuse their derivative aspects. Plenty of others, though, are too beholden to their forebears to offer anything distinctive.

Sci-fi thrills

I Am Mother’s ambitions are twofold. On one hand, it continues the tradition of speculative fiction by populating its story with questions of agency, ethics and more besides. On the other, it strives for baser thrills, progressively unpacking a cache of twists through a narrative labyrinth thick with tension.

Judged purely as a sci-fi thriller – setting its lofty ideas to the side for a moment – I Am Mother is often admirable, particularly in light of the limitations associated with its production. Helmed by a first-time director on a moderate budget (partly funded by the Adelaide Film Festival, where it premiered in 2018 as a work-in-progress before screening at a slew of festivals in 2019 and being snapped up by Netflix), the film rarely betrays its modest origins. The production design is immaculate throughout, presumably thanks to Hugh Bateup (who’s contributed to the likes of the Wachowskis’ Matrix trilogy – another significant influence!). Mother’s utilitarian bunker adopts the sleek industrial aesthetic common in contemporary science-fiction, while the droid herself – realised not through CGI but by an actor performing in a suit – is equal parts menacing and maternal without ever coming off as chintzy, as is so often the case in cheaply made genre flicks.

When the film’s budgetary limitations do become apparent – as when Rugaard’s and Swank’s characters venture out into the barren wasteland awaiting them outside Mother’s sanctum – Sputore has smartly spun such shortcomings into strengths. Images of the pair wandering through mechanised landscapes as autonomous machines terraform a desolate Earth, or of them standing atop a hill above scattered shipping containers across blackened sand, aren’t convincingly realistic. But the use of colour – Daughter’s crimson jumpsuit and vibrant green plants against an ashen backdrop – ensures that the film etches a unique aesthetic.

The acting, too, impresses. Byrne’s careful enunciation and edge of tight cheeriness hit just the right note for Mother’s subtly nefarious demeanour, while Swank’s air of frantic energy successfully embodies the paranoia born of scrabbling for survival in a post-apocalyptic wilderness populated by murderous droids. But Rugaard is the highlight. Starring in only her fourth feature, she’s required to shoulder the heaviest load in this three-hander, and never hits a false emotional note.

Sadly, the same can’t be said for her characterisation. For a girl raised solely by a robot – aside from, oddly, the occasional episode of Johnny Carson’s Tonight Show – she has none of the stiffness or awkwardness you’d expect from such an unconventional upbringing. Instead, Daughter is written as a typically spirited teenager with only a slender connection to the only parent she’s ever known: she’s very quick to question Mother upon hearing Swank’s stories. This ultimately undermines I Am Mother’s ability to succeed as a pure thriller, since thrillers rely heavily on their audience’s connection to their imperilled characters.

I Am Mother’s ambitions are twofold. On one hand, it continues the tradition of speculative fiction by populating its story with questions of agency, ethics and more besides. On the other, it strives for baser thrills, progressively unpacking a cache of twists through a narrative labyrinth thick with tension.

Daughter’s readiness to interrogate the bounds of her reality fundamentally undermines Sputore’s attempts to engender suspense. On paper, the film’s premise is perfectly geared to develop and sustain tension, as a seemingly simple scenario is complicated by inquiries, distrust and eventual twists (like Daughter’s discovery of an incinerated human skeleton, suggesting earlier ‘Daughters’ were murdered after failing to meet the droid’s ethical expectations – more on that later). But I’d argue that the screenplay tips its hand too early; there’s something off about Mother from her first interactions with Daughter, so the net effect is one of impatience for the inevitable conflict to arise rather than uncertainty about where the story is heading.

Granted, there are further twists in the film’s final act that I didn’t see coming. When Swank’s and Rugaard’s characters escape from Mother’s outpost, I was genuinely surprised to find that all the talk of mines and humans hiding out from the droids was a lie, with the older woman living in isolation in an abandoned shipping container. Equally, realising that this woman was likely the first Daughter, deliberately kept alive as an ‘exam’ for Rugaard’s Daughter, was unexpected (and, admittedly, ambiguous – this fact isn’t made explicit in the film proper, but seems a safe bet upon reflection[3]We first see Mother setting the gestation of a human embryo in progress one day after the extinction event, according to the intertitles. But, when we cut ahead to Daughter as a teenager, 13,867 days have passed: or, if you do the maths, roughly thirty-eight years. It’s therefore clear that the first baby we see is not Daughter, and is likely Swank’s character – but it’s never explicitly spelled out.). These twists, however, are almost academic in their execution, lacking the incisive shock that a great thriller requires.

Android ethics

While I Am Mother might flounder as a thriller – James Cameron this ain’t – it’s clear that Sputore and Green have ambitions beyond pure genre pleasures. The film is bursting with ideas in the way that only a debut feature can be, with the creators cramming their story with as many thorny questions around artificial intelligence (AI) and metaphysics as a first-year philosophy textbook.

The idea that resonated with me was the question of passivity in the face of catastrophe. Perhaps it’s just that I sat down to write this in the wake of September 2019’s Climate Strike,[4]See ‘As It Happened: Climate Protests Sweep the World’, BBC News, 21 September 2019, <https://www.bbc.com/news/live/world-49753710>, accessed 30 September 2019. but Daughter’s predicament chimes with the dilemma faced by our corroding climate. She lives in comfortable confines – luxury compared with the devastation outside her doorstep – but the arrival of Swank’s interloper challenges her complacency. When she learns of supposed communities of survivors taking shelter in abandoned mines, can she justify remaining in the comparative safety of Mother’s outpost, regardless of the droid’s intentions?

I Am Mother intertwines its ethics with questions of parenting – how can you pass on your ethical beliefs to your children? – and a dash of the spiritual, with the droid essentially fulfilling the role of ‘creator’ for a new iteration of humanity.

With a climate-change lens filtering the film’s vision, it struck me as optimistic when Daughter breaks from Mother’s bonds to venture into the post-apocalyptic wastes. Risky, certainly. But she’s making a conscious decision to choose community – to choose hope – over comfort. As a comfortably middle-class Australian with the confidence I’ll be able to weather the storms (literal and figurative) wrought by climate change, I found that the scene at once challenged me – in particular, my decision to prioritise work over attending said Climate Strike – and assuaged my anxiety about our future as a species.

The power of this moment made the subsequent discovery of Swank’s character’s isolation all the more deflating, even devastating. There’s no community, no hope for the future, the glimmer of optimism that typically shines out from beneath the muck of post-apocalyptic narratives smothered underneath a robotic jackboot. For me, the twist embodied all my fears about our encroaching climate catastrophe: a vision of a future in which the privileged few silo themselves off as the many suffer and die. Heavy stuff.

Thing is, I’m not entirely convinced any of this subtext is intended. That’s not to say it’s accidental; as with any good piece of speculative fiction, I Am Mother keeps its metaphors vague enough to allow for multiple interpretations. More power to Sputore and Green, then, that the film had such an impact on me. But its conclusion – wherein Daughter returns to the outpost to raise her ‘brother’ (a recently born embryo) without Mother’s supervision – displays less interest in the ramifications of the post-apocalyptic setting than in a whole bevy of other concerns.

Specifically, I Am Mother’s thematic locus circles two poles: parenting and ethics, the latter especially in relation to AI. We come to learn that the ‘extinction event’ was engineered by Mother (not a single droid but an interconnected AI controlling a huge network of robots) in an attempt to protect human life.[5]There are shades of scientist and sci-fi writer Isaac Asimov here; it’s suggested that this goal of protecting human life is Mother’s prime directive, so to speak. That her interpretation of this task was to eradicate the majority of the species from the Earth will be familiar to readers of Asimov and the technicalities associated with his ‘three laws of robotics’. For more on this, see George Dvorsky, ‘Why Asimov’s Three Laws of Robotics Can’t Protect Us’, Gizmodo, 20 April 2016, <https://www.gizmodo.com.au/2016/04/why-asimovs-three-laws-of-robotics-cant-protect-us/>, accessed 11 October 2019. An ethics lesson between Mother and Daughter early in the film suggests that Mother’s ethical framework is a perverse kind of collectivism, with the droid implying that a sick patient should be allowed to die so that their organs can save other individuals.

It becomes clear by the film’s end that Daughter is likely the third attempt[6]This is never made explicit, but given that her ID code – shown on screen – ends in ‘03’, it’s a reasonable assumption. to impose this kind of ethics on a human in the interest of sustaining the human population in the mode Mother prefers. As such, I Am Mother intertwines its ethics with questions of parenting – how can you pass on your ethical beliefs to your children? – and a dash of the spiritual, with the droid essentially fulfilling the role of ‘creator’ for a new iteration of humanity.

I Am Mother’s conclusion is ambiguous. Mother allows Daughter to raise a new generation of children in her absence, and the former’s (implied) murder of Swank’s character suggests that the droid sees this end result as a successful execution of her plan. This is intended to be a thought-provoking ending – the kind that would see you debating its ins and outs with your friends on the way out of the theatre (had the film actually received a theatrical release[7]The film was originally slated for theatrical release in Australia through StudioCanal, but, following its purchase by Netflix in February, it was seemingly dropped without announcement from the distributor’s slate.) – but the execution leaves a bit to be desired. In particular, the overlap between the film’s examinations of parenting and ethics is unsatisfactory; if it took Mother three tries to ‘successfully’ raise someone to adopt her intended ethical outlook, only for that person to quickly challenge it, surely the likelihood of Daughter’s children – let alone their children – following in her footsteps is slim to none. And, with Mother presumably driven by machine logic rather than emotions, it’s hard to swallow the film’s presentation of its conclusion as a kind of happy ending for the droid.

Still, the film undoubtedly provokes questions from its audience, even if one of them is, ‘Wait, does this actually add up?’ For all the debts it may owe to the decades of sci-fi cinema preceding it, I Am Mother is ultimately an uneven work that is also distinctive, setting itself apart from its more forgettable genre compatriots.

https://www.netflix.com/au/title/80227090

Endnotes

| 1 | Grant Sputore, quoted in Brad Gullickson, ‘Talking Love and Robots with the Director of I Am Mother’, Film School Rejects, 15 June 2019, <https://filmschoolrejects.com/i-am-mother-director/>, accessed 11 October 2019. |

|---|---|

| 2 | ibid. |

| 3 | We first see Mother setting the gestation of a human embryo in progress one day after the extinction event, according to the intertitles. But, when we cut ahead to Daughter as a teenager, 13,867 days have passed: or, if you do the maths, roughly thirty-eight years. It’s therefore clear that the first baby we see is not Daughter, and is likely Swank’s character – but it’s never explicitly spelled out. |

| 4 | See ‘As It Happened: Climate Protests Sweep the World’, BBC News, 21 September 2019, <https://www.bbc.com/news/live/world-49753710>, accessed 30 September 2019. |

| 5 | There are shades of scientist and sci-fi writer Isaac Asimov here; it’s suggested that this goal of protecting human life is Mother’s prime directive, so to speak. That her interpretation of this task was to eradicate the majority of the species from the Earth will be familiar to readers of Asimov and the technicalities associated with his ‘three laws of robotics’. For more on this, see George Dvorsky, ‘Why Asimov’s Three Laws of Robotics Can’t Protect Us’, Gizmodo, 20 April 2016, <https://www.gizmodo.com.au/2016/04/why-asimovs-three-laws-of-robotics-cant-protect-us/>, accessed 11 October 2019. |

| 6 | This is never made explicit, but given that her ID code – shown on screen – ends in ‘03’, it’s a reasonable assumption. |

| 7 | The film was originally slated for theatrical release in Australia through StudioCanal, but, following its purchase by Netflix in February, it was seemingly dropped without announcement from the distributor’s slate. |