Costume designer Orry-Kelly once quipped, ‘Hell must be filled with beautiful women and no mirrors.’[1]Orry-Kelly, quoted in Jay Jorgensen & Donald L Scoggins, ‘Orry-Kelly’, in Creating the Illusion: A Fashionable History of Hollywood Costume Designers, Running Press, Philadelphia, 2015, p. 166. His talent for dressing female Hollywood actors is abundantly evident in Gillian Armstrong’s 2015 biographical documentary, Women He’s Undressed. But the film is a poor reflection of the man himself, who remains enigmatically absent.

Born Orry George Kelly in 1897, in the New South Wales South Coast town of Kiama, Kelly became the in-house costume designer at Warner Bros. in 1932, and remained with the company until 1944. He then worked for 20th Century Fox until 1947, after which he freelanced for Warner, Fox, MGM and United Artists. He designed costumes for 285 films, including 42nd Street (Lloyd Bacon, 1933), Casablanca (Michael Curtiz, 1942), Oklahoma! (Fred Zinnemann, 1955) and Gypsy (Mervyn LeRoy, 1962).

Armstrong’s documentary takes as its starting point the paradox that, in Australia, Kelly has largely been forgotten, while in Hollywood, it’s been forgotten that he was Australian. Until Catherine Martin’s Oscar wins for costume and production design in The Great Gatsby (Baz Luhrmann, 2013), Kelly was the Australian who had won the most Academy Awards. He earned three, all for costume design: for An American in Paris (Vincente Minnelli, 1951), Les Girls (George Cukor, 1957) and Some Like It Hot (Billy Wilder, 1959).[2]See Garry Maddox, ‘Orry-Kelly’s Three Lost Oscars Are Coming Home’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 29 May 2015, <http://www.smh.com.au/entertainment/movies/orrykellys-three-lost-oscars-are-coming-home-20150529-ghbrba.html>, accessed 21 October 2015. Women He’s Undressed is strongest when describing what made Kelly’s work so special. But Armstrong’s dramatisation of her subject’s private life feels tendentious and never entirely convincing.

Creating an on-screen body

Costume designers are instrumental to the tone and genre of a film, to its sense of spectacle, and to our understanding of its characters. Yet their work is frequently confused with fashion design or wardrobe styling: misunderstood as merely the creation and selection of pretty dresses. Furthermore, costume designers are rarely celebrities like actors or directors, even though screen costumes can be iconic and culturally influential. This is why it’s such a joy that Women He’s Undressed doesn’t merely celebrate Orry-Kelly as a purveyor of Golden Age screen glamour. Instead, it depicts him as a thoughtful manipulator of aesthetics and fabrics, who could actually sculpt the on-screen appearance of women’s bodies.

Women He’s Undressed doesn’t merely celebrate Orry-Kelly as a purveyor of Golden Age screen glamour. Instead, it depicts him as a thoughtful manipulator of aesthetics and fabrics, who could actually sculpt the on-screen appearance of women’s bodies.

And the people who explain this are experts. Badly made documentaries simply have their talking heads praise or reminisce about the subject of the film; in contrast, Women He’s Undressed showcases the professional views of Kelly’s successors, whose work is also brilliant and significant. These interviewees include the Australian costume designers Catherine Martin, Kym Barrett (who worked on the Matrix films, The Wachowskis, 1999–2003) and Michael Wilkinson (American Hustle, David O Russell, 2013); American designers Ann Roth (The English Patient, Anthony Minghella, 1996) and Colleen Atwood (Alice in Wonderland, Tim Burton, 2010); and costume historian and designer Deborah Nadoolman Landis (Raiders of the Lost Ark, Steven Spielberg, 1981), who curated the major Hollywood Costume exhibition held at the Australian Centre for the Moving Image in 2013.

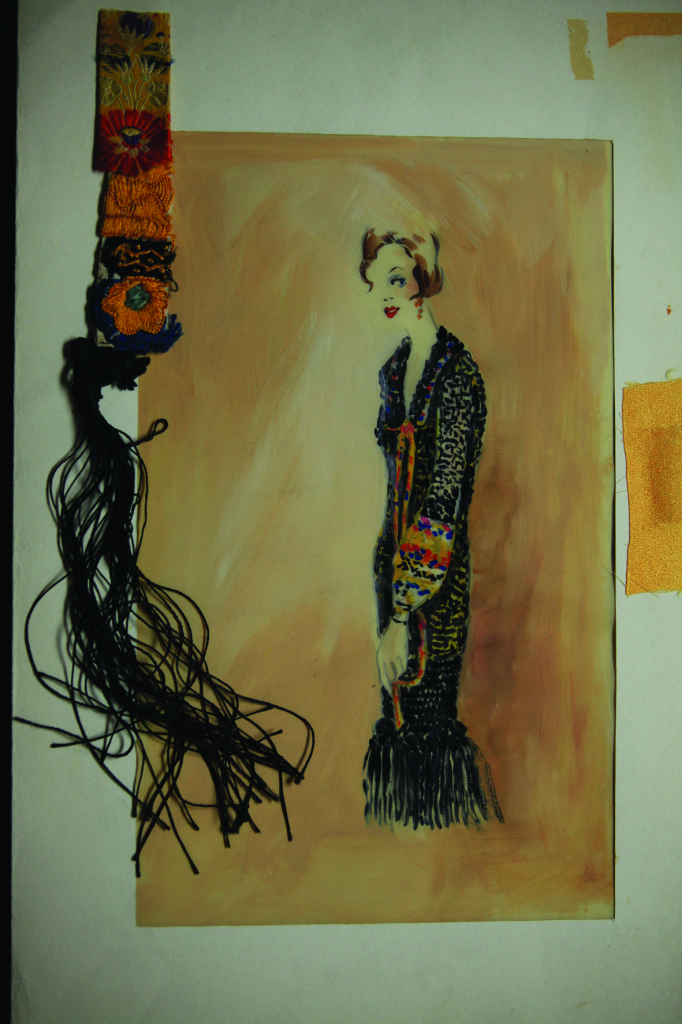

As they – and others, including actors Jane Fonda and Angela Lansbury – explain, Kelly’s signature style favoured simple, fluid lines that appeared to reveal the body but, in fact, created its shape through tailoring and texture. His theatrical background is evident in his costumes for showgirl and performer characters – women whose physicality is about playful display. These figure-hugging outfits frequently involve handpainted fabrics, intricate beading, and embroidery. Kelly’s work was a perfect fit for the large-scale set pieces in which director Busby Berkeley specialised, transforming pretty showgirls into abstract tableaux. In Gold Diggers of 1933 (Mervyn LeRoy, 1933, with musical numbers by Berkeley), Kelly created costumes for the famous ‘We’re in the Money’ sequence, with showgirls dressed as gold coins and Ginger Rogers wearing beige-toned soufflé mesh, appearing nearly nude except for strategically positioned spare change.

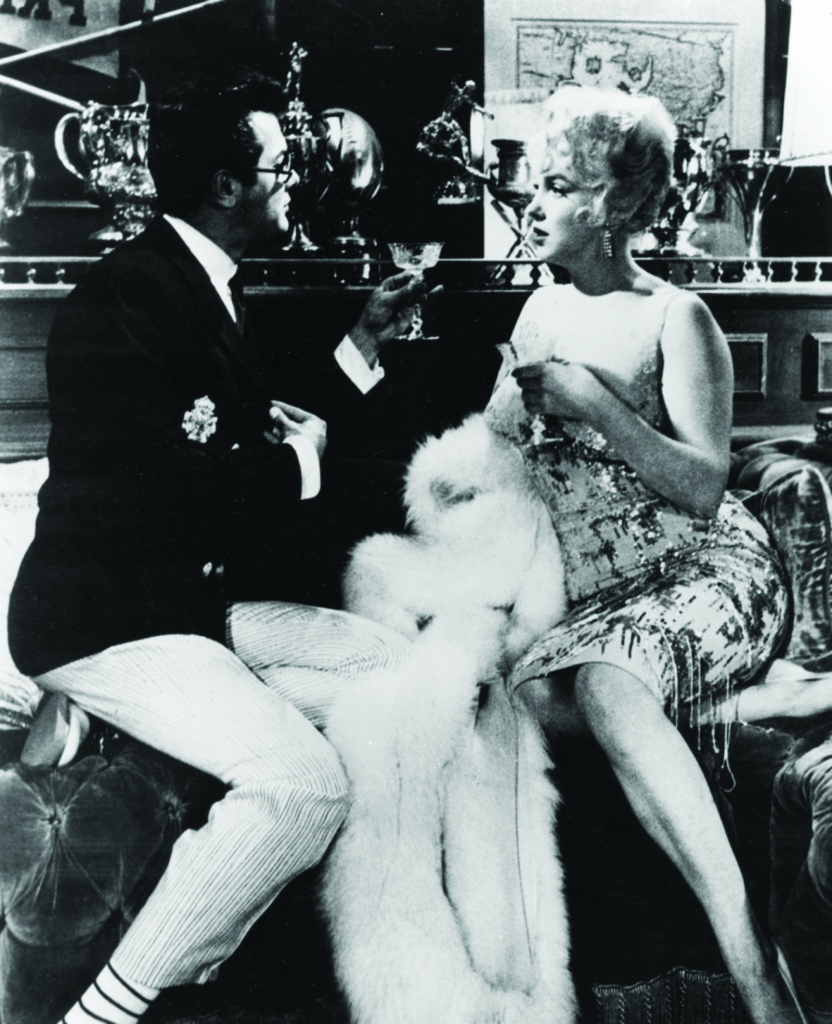

From 1934, when rigorous enforcement of the 1930 Motion Picture Production Code began to preclude lasciviously skimpy costuming, Kelly’s work began to suggest sexuality without revealing skin. For the Betty Grable vehicle The Dolly Sisters (Irving Cummings, 1945), Kelly created an evening gown covered in handpainted eyes – including one staring from each breast. And, in Gypsy, he transformed gamine Natalie Wood into a curvaceous burlesque stripper using strategic padding and vertical lines. Notably, Marilyn Monroe’s sheer, bias-cut flapper dresses in Some Like It Hot are much sexier for suggesting, rather than revealing, the actor’s famous assets. Spotlit as she sings ‘I Wanna Be Loved by You’, she’s innocent, yet seems clad only in spangles. But film audiences never saw the beige-and-silver dress’s most adorable, theatrical detail: a heart-shaped cut-out on the left buttock, edged in red.[3]Garry Maddox, ‘Stitches in Time’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 30 May 2015, <http://www.smh.com.au/interactive/2015/orry-kelly/>, accessed 21 October 2015.

Kelly often favoured colours. Bette Davis’ scandalous dress in Jezebel (William Wyler, 1938) was really a rusty bronze, but was designed to register believably as ‘red’ in black-and-white. And block colour is integral to the title characters of Auntie Mame (Morton DaCosta, 1958) and Irma La Douce (Billy Wilder, 1963). We recognise Mame’s (Rosalind Russell) screwball free-spiritedness in her tangerine, lime, ruby and cobalt ensembles, and Irma’s (Shirley MacLaine) hipness in the emerald-green of her bra, chiffon blouse, tights and hair ribbon. But Kelly’s creation of character could be subtle and naturalistic, too. The pale simplicity of Casablanca’s evening wear, hats and trench coats showcased Ingrid Bergman’s luminosity and Humphrey Bogart’s regret.

At a time when many queer people in Hollywood were closeted, it’s striking that Kelly never tried to hide his homosexuality, and was never professionally penalised for it.

Still, Kelly’s most famous collaboration was with Davis, who compared his departure from Warner Bros. to ‘los[ing her] right arm’.[4]Bette Davis, quoted in Jorgensen & Scoggins, op. cit., p. 171. ‘I think of Bette Davis as a period piece,’ Kelly had said. ‘Working with Bette isn’t easy, but she’s worth it. She is honest and outspoken.’[5]Orry-Kelly, quoted in Jorgensen & Scoggins, ibid. Her short torso and large breasts made Davis difficult to dress in the 1930s, which favoured tall, sylph-like figures. But, while Kelly could and did tailor contemporary clothing to make her beautiful, both actor and designer fought to present her as unsympathetic, even ugly, against the studio’s demands for glamour. In the melodrama Mr. Skeffington (Vincent Sherman, 1944), for example, Kelly’s costumes became progressively more ridiculous and unflattering, transforming Davis from a self-absorbed socialite to a reclusive, embittered invalid. ‘With Orry there was a great deal of input into the character, and that’s what Bette really liked about him,’ Armstrong says. ‘They were brave, and that was their bond.’[6]Gillian Armstrong, quoted in Stephen A Russell, ‘Women He’s Undressed: Gillian Armstrong on Her Quest to Take the Dust Covers off a Legend’, SBS Movies, 11 June 2015, <http://www.sbs.com.au/movies/article/2015/06/11/women-hes-undressed-gillian-armstrong-her-quest-take-dust-covers-legend>, accessed 22 October 2015.

Reinscribing an Australian identity

Early in Women He’s Undressed, Ann Roth – who worked with Kelly on Oklahoma! early in her career – expresses astonishment at his current obscurity in his homeland: ‘You say nobody knows who he is? Who doesn’t know who he is?’ Yet claiming credit for a local kid’s international success is something of an Australian media hobby and, at the height of Kelly’s fame, the Australian press was paying attention to ‘Our Orry’. ‘They interviewed him like you would Hugh Jackman now,’ Armstrong says.[7]ibid. Indeed, aspiring Australian creatives continue in the designer’s footsteps from global periphery to centre.

Aged seventeen, Kelly moved to Sydney to become a banker, but instead studied art and became fascinated by the city’s theatre scene and criminal demimonde. Then he went to New York in 1922 to be an actor, but found his vocation as a designer of murals, handpainted silk ties, theatre sets and costumes, and movie title cards. In 1931, he settled permanently in Los Angeles. Kelly made regular visits home to his mother, Florence, and corresponded with her often. With these letters, Florence Kelly was keeping The Sydney Morning Herald updated on her son’s activities.[8]Jane Freebury, ‘Women He’s Undressed: Gillian Armstrong Tells the Story of Fashion Designer Orry-Kelly’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 5 July 2015, <http://www.smh.com.au/entertainment/movies/women-hes-undressed-gillian-armstrong-tells-the-story-of-fashion-designer-orrykelly-20150703-gi4c5p.html>, accessed 22 October 2015. However, after she died in 1949, Kelly stayed in the US, and the local press coverage dried up. His death in 1964 attracted ‘a two-line obituary in Australia’, Armstrong says, ‘but in America there was a huge article in Variety, in The Hollywood Reporter and both the New York Times and the LA Times’.[9]Armstrong, quoted in Russell, op. cit.

Women He’s Undressed seeks to redress this neglect by viewing Kelly’s life and career through the prism of a larrikinish Australianness. Alongside archival stills and footage, talking-head interviews and voiceover actors performing archival commentary from those who knew Kelly, Armstrong has reprised the technique she used in her 2006 documentary, Unfolding Florence: The Many Lives of Florence Broadhurst – in monologue sequences performed to-camera, actor Darren Gilshenan plays Kelly, and Deborah Kennedy, his mother. The film’s screenwriter, Katherine Thomson, based Gilshenan’s monologues on Kelly’s own words, as found in archival interviews, letters and his syndicated wartime newspaper column, ‘Hollywood Fashion Parade’. Armstrong explains:

We also had very little footage [of Kelly] – no one films a costume designer and there were only the press stills that the studio would take, so we finally just thought we’d bite the bullet and have him speak to you.[10]Gillian Armstrong, quoted in Stephen Saito, ‘TIFF ’15 Interview: Gillian Armstrong on Finding Freedom in Documentaries and Women He’s Undressed’, The Moveable Fest, 14 September 2015, <http://moveablefest.com/moveable_fest/2015/09/gillian-armstrong-women-hes-undressed.html>, accessed 22 October 2015.

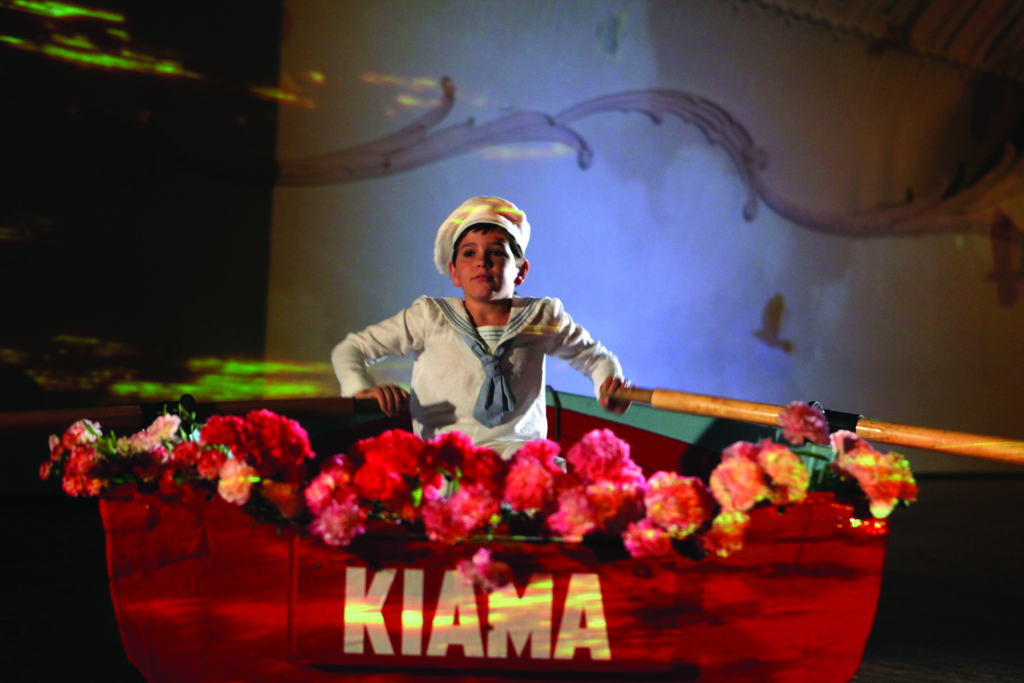

Armstrong was struck by an archival portrait of Kelly as a small boy in Kiama, standing beside a small boat, and recounts that

there was so much poetry in the fact he’s in a sailor suit that his father, who was a tailor, obviously made. Then for an Australian, the story is so much about leaving and crossing oceans to go across the world.[11]ibid.

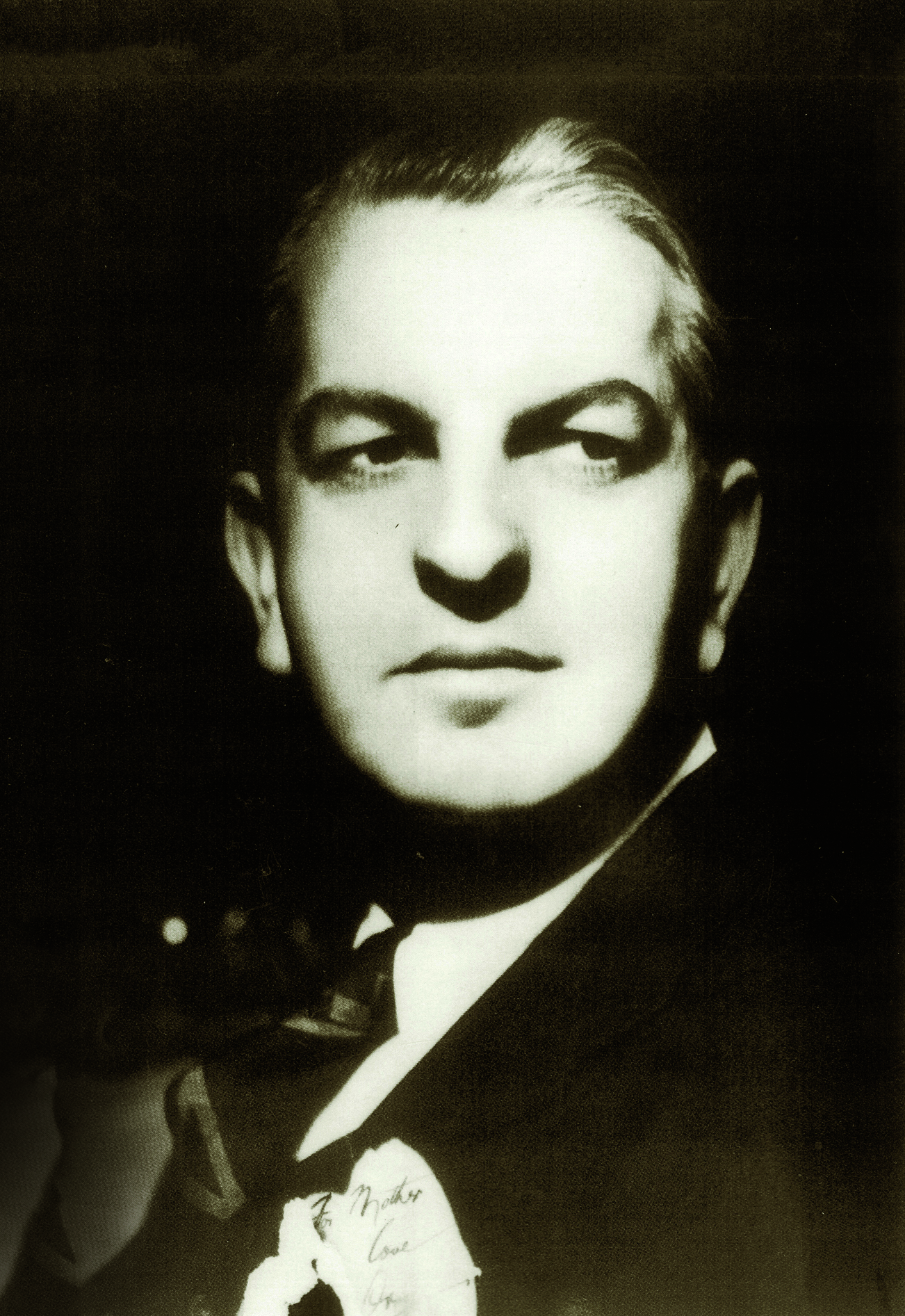

These monologue sequences are intentionally artificial, even dreamlike. Gilshenan reclines in a red dinghy on an empty sound stage, with projected imagery behind him, or rows the boat in a real ocean. Kennedy hangs out laundry, then sits at a dressing table, on a seaside clifftop. Perhaps these sequences are intended to ‘bring Kelly home’ by immersing him in a particularly Australian landscape and language of kitsch. Instead, however, the monologues are jarringly pantomimish. The puckish Gilshenan bears little physical resemblance to the real Kelly, who looked fierce yet lugubrious, like a cross between Alfred Hitchcock and Clark Gable. It’s disquieting that, in attempting to repatriate Kelly, Armstrong and Thomson have shoehorned into their own didactic narrative the real words of an Australian who chose never to return home.

Crafting a narrative of personal disappointment

Women He’s Undressed tips its hand in another way when it describes 1930s Los Angeles as ‘the most homophobic city in the world’. This is somewhat hyperbolic. However, at a time when many queer people in Hollywood were closeted, it’s striking that Kelly never tried to hide his homosexuality, and was never professionally penalised for it. Rather, he was protected by his friendships with powerful industry insiders, including studio boss Jack Warner’s wife Ann and gossip columnist Hedda Hopper.

Kelly could be hilariously bitchy among friends, and a fiery-tempered, bullying perfectionist at work. He was especially mean when he was on the booze – it was liver cancer that caused his premature death. Yet he was no aggressive self-promoter: one reason his memoir Women I’ve Undressed remained unpublished for such a long time was because he refused to be a ‘scandal monger’ dishing dirt on his peers.[12]Jorgensen & Scoggins, op. cit., p. 174. However, Women He’s Undressed pursues a narrative as melodramatic as any of the Bette Davis films Kelly costumed: that of a lonely man, callously spurned by his one true love. In New York, Kelly met a young English actor, Archibald Leach. Along with a third thespian housemate, they shared a Greenwich Village apartment – and possibly were lovers. It was Leach’s agent who helped Kelly secure his job at Warner Bros. But, in Hollywood, Leach reinvented himself as Cary Grant, and cold-shouldered his former friend in public for fear of being outed. It was Grant’s public-relations people, the film suggests, who had stymied the publication of Kelly’s potentially damaging memoir.

It’s a tantalising yarn. But Armstrong treats it credulously, implying that Grant’s snubbing of Kelly was malicious, and that it provoked, or exacerbated, Kelly’s mood swings and alcoholism. Such a characterisation fails to convince because it seeks a definitive interpretation of these men’s lives, whereas celebrity gossip is pleasurable because it comes unmoored from objective truths. As Hollywood gossip historian Anne Helen Petersen has argued: ‘we’ll never know whether Grant was or was not gay, and it does not matter […] he could mean so many exquisite, beautiful things to so many different people.’[13]Anne Helen Petersen, ‘Scandals of Classic Hollywood: Cary Grant’s Intimate Bromance’, The Hairpin, 21 December 2011, <http://thehairpin.com/2011/12/scandals-of-classic-hollywood-cary-grants-intimate-bromance/>, accessed 22 October 2015.

In the documentary’s final moments, Armstrong reveals that Kelly’s memoir, long thought to be lost, had been rediscovered, tucked into a pillowcase in the care of a relative. The book has at last been published.[14]Orry-Kelly, Women I’ve Undressed: The Fabulous Life and Times of a Legendary Hollywood Designer and a Genuine Australian Original, Ebury Press, Sydney, 2015. I’m not sure this works as a ‘final reveal’ – the monologues might have felt more authentic, had we known where they originated. Similarly, Armstrong withholds pictures and footage of the real Kelly until very late in the film, presumably to avoid breaking the spell of the monologue scenes. However, a brief clip showing Kelly’s Oscar acceptance speech is instantly charming and relatable, which only makes the monologues seem weirder and more alienating.

It’s a shame that such quirky impulses preoccupy Women He’s Undressed. As a means of recuperating Orry-Kelly’s Australian reputation for excellence in his field, it’s already strong enough without needing distracting fripperies about travel or romantic disappointments. His beautiful women reflect themselves.

http://www.womenhesundressed.com

Endnotes

| 1 | Orry-Kelly, quoted in Jay Jorgensen & Donald L Scoggins, ‘Orry-Kelly’, in Creating the Illusion: A Fashionable History of Hollywood Costume Designers, Running Press, Philadelphia, 2015, p. 166. |

|---|---|

| 2 | See Garry Maddox, ‘Orry-Kelly’s Three Lost Oscars Are Coming Home’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 29 May 2015, <http://www.smh.com.au/entertainment/movies/orrykellys-three-lost-oscars-are-coming-home-20150529-ghbrba.html>, accessed 21 October 2015. |

| 3 | Garry Maddox, ‘Stitches in Time’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 30 May 2015, <http://www.smh.com.au/interactive/2015/orry-kelly/>, accessed 21 October 2015. |

| 4 | Bette Davis, quoted in Jorgensen & Scoggins, op. cit., p. 171. |

| 5 | Orry-Kelly, quoted in Jorgensen & Scoggins, ibid. |

| 6 | Gillian Armstrong, quoted in Stephen A Russell, ‘Women He’s Undressed: Gillian Armstrong on Her Quest to Take the Dust Covers off a Legend’, SBS Movies, 11 June 2015, <http://www.sbs.com.au/movies/article/2015/06/11/women-hes-undressed-gillian-armstrong-her-quest-take-dust-covers-legend>, accessed 22 October 2015. |

| 7 | ibid. |

| 8 | Jane Freebury, ‘Women He’s Undressed: Gillian Armstrong Tells the Story of Fashion Designer Orry-Kelly’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 5 July 2015, <http://www.smh.com.au/entertainment/movies/women-hes-undressed-gillian-armstrong-tells-the-story-of-fashion-designer-orrykelly-20150703-gi4c5p.html>, accessed 22 October 2015. |

| 9 | Armstrong, quoted in Russell, op. cit. |

| 10 | Gillian Armstrong, quoted in Stephen Saito, ‘TIFF ’15 Interview: Gillian Armstrong on Finding Freedom in Documentaries and Women He’s Undressed’, The Moveable Fest, 14 September 2015, <http://moveablefest.com/moveable_fest/2015/09/gillian-armstrong-women-hes-undressed.html>, accessed 22 October 2015. |

| 11 | ibid. |

| 12 | Jorgensen & Scoggins, op. cit., p. 174. |

| 13 | Anne Helen Petersen, ‘Scandals of Classic Hollywood: Cary Grant’s Intimate Bromance’, The Hairpin, 21 December 2011, <http://thehairpin.com/2011/12/scandals-of-classic-hollywood-cary-grants-intimate-bromance/>, accessed 22 October 2015. |

| 14 | Orry-Kelly, Women I’ve Undressed: The Fabulous Life and Times of a Legendary Hollywood Designer and a Genuine Australian Original, Ebury Press, Sydney, 2015. |