Positing a world where body-swap technology has become a reality, Pulse (Stevie Cruz-Martin, 2016) poses a complex question: just because you can dispense with perceived physical problems, should you? Apocryphal cliché or not, ‘be careful what you wish for’ is an apt adage in this circumstance.

A refreshingly candid and, at times, challenging exploration of the intersections between gender, sexuality and disability, Pulse does not shy away from the thornier aspects of its central premise. A deeply personal story drawn from the real-life experiences of writer and star Daniel Monks, who is hemiplegic, it is a sterling example of speculative fiction treading lightly as a means to inspire thoughtful, debate-instigating discussion.

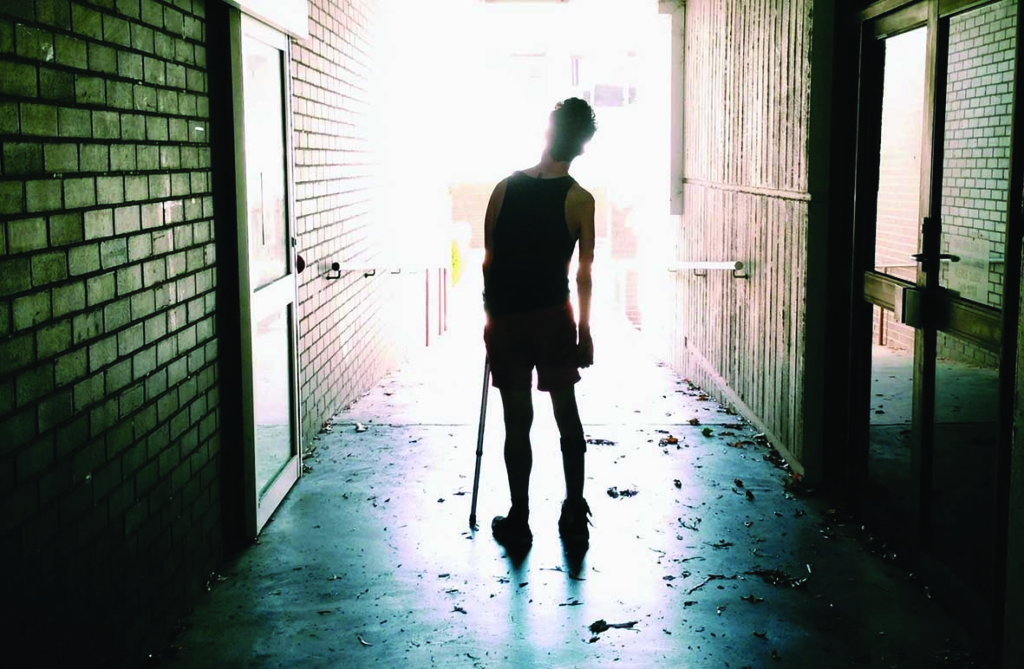

Monks only slightly tweaks his childhood experience of disability in order to explore the effects of technological advances on our understanding of who we are. Far from the dystopian future of Blade Runner (Ridley Scott, 1982) and its android conundrum, Pulse is recognisably set in today’s world – though, granted, one where medical progress allows for the transference of a person’s consciousness into a new body. Monk plays high school teenager Olly, whom we first see on a hospital bed being prepped for this very operation, though the reason behind it is not made immediately apparent. In a moment of documentary-like truth, the scene is intercut with childhood footage of Monks in the aftermath of surgery, an intimate glimpse into a vulnerable point in his young life.

When Monks was eleven years old, a large tumour was discovered on his cervical spinal cord. Though it thankfully turned out to be benign, sadly, complications with the biopsy initially left Monks quadriplegic. Beginning Year 7 in a wheelchair and undergoing six months of intense rehabilitation had a profound effect on Monks’ confidence, particularly as he was also just beginning to grapple with his homosexuality. He tells me:

As a kid, I was always incredibly healthy, very physical. I did every type of dance class and was quite a performer. My mother, Annie, was an actress then a casting director, so I kind of grew up performing. Going back to school in a wheelchair and realising that I might be gay was really hard, and there was a lot of trying to be someone I’m not.

Writing for The HubStudio, a resource and development centre for professional actors, about the effects of this drastic change on his ambitions, Monks elaborates:

Going from that incredibly physical child to a freshly disabled one took the life out of me. I gave up acting, deeming that because of my disability, it would no longer be a ‘feasible’ career path. I buried my love for it deep within me, and going into high school, was embarrassed when anyone mentioned my past performances and the child I once was.[1]Daniel Monks, ‘The Accessibility of Acting’, The HubStudio website, 31 January 2017, <http://www.thehubstudio.com.au/the-accessibility-of-acting/>, accessed 19 May 2017.

Growing pains

Far more interested in the human experience, Pulse does not dwell on the not-that-far-off-reality mechanics of its narrative’s body-swap technology, nor does it cite the reasons for Olly’s hemiplegia. Instead, it focuses on the tumultuous emotions he must grapple with within a recognisable coming-of-age context. Like any hormonal teenager, Olly is beginning to push back against the overbearing protectiveness of his mother, Jacqui (Caroline Brazier), and even demonstrates a certain antagonism towards her partner, Mark (Troy Rodger), whom he considers less intelligent than him. After detailing some of the day-to-day difficulties of his deteriorating physical condition and the stress that places on the family dynamic, Jacqui brings up the option of the body swap, mentioning that the surgical advance has become commonplace in both the US and Europe.

Resisting at first, Olly eventually opts to explore the possibility – a decision inexorably tied to his burgeoning sexuality. In the first of several key scenes set on a dance floor, amid a sea of strobing red and blue neon lights, there’s a palpable melancholy as Olly observes his best friends Luke (Scott Lee), on whom he has an unspoken crush, and Nat (Sian Ewers) kissing. When, the following day, his assumption of an after-school hangout is crushed by their wish to go it alone on a movie date, it’s a clear flashpoint in a fateful decision tied up with Olly’s increasing loneliness, secrecy and a certain degree of self-loathing. These sentiments are ones that Monks knows only too well:

One of my earliest memories when I went back to school in a wheelchair was of seeing this really cute boy I had a bit of a crush on kissing this pretty blonde girl, and I remember thinking, ‘If only I looked like her, he’d be looking at me the exact way he’s looking at her right now.’

Feeling disconnected from his own body, Monks absolutely wished to become that girl, to wish away both his newly acquired disability and his concealed sexuality, believing that life would be easier that way. Olly’s subsequent decision to transfer his consciousness into an able-bodied woman of equal age, now identifying as Olivia (Jaimee Peasley), becomes an intriguing case of wish-fulfilment, Monks notes.

I was interested in [questioning] how much do our bodies make us who we are, and also how people respond to us. It was […] my own story – going through that and feeling like a burden, to then embracing myself and what makes me different – that formed the basis of Pulse. That journey for me was from age twelve to twenty-five, but in the film it’s over the course of a month or two.

‘There have been such huge strides in queer filmmaking, but the thing that I found, and a huge influence in making Pulse, was that I had never seen a film that spoke to what it was actually like to be a young person with disability and to struggle with it.’

– Daniel Monks

What’s in a name?

Olly’s decision to become Olivia is confronting for his mother, who at first questions it within the framework of transitioning, though her lack of understanding is demonstrated by her use of the inaccurate term ‘transsexual’. Olly does not identify as a woman per se; he sees it simply as a means to circumvent the already-complicated path of coming out in a situation he perceives to be aggravated by his acquired disability.

His reluctance to grapple with his sexuality is underlined when it’s made clear, just prior to the operation, that neither Luke nor Nat are aware of his homosexuality. The ramifications of Olly’s body swap, and of his crush on Luke, place a great deal of strain on these previously solid bonds that’s already exacerbated by Nat and Luke’s redefined relationship. As a result, Olivia turns increasingly to the free-spirited Britney (Isaro Kayitesi), who is initially antagonistic about the body swap, describing it as ‘gross’ in a way that evokes both homophobia and transphobia. Their evolving friendship follows the recognisable rebellion of young adulthood, mixed up, as is often the case, with heavy drinking and emerging sexual exploration.

Pulse’s second integral party scene tackles the complexity of identity politics within the body-swap context. Director Cruz-Martin further queers Olivia’s newfound freedom by cutting between Peasley and Monks, considerably altering the dynamic of any given scene. This is particularly of note when Olivia drunkenly kisses homophobic bully Brandon (David Richardson) while Luke watches on in disbelief.

Olivia ultimately loses her virginity to Brandon, who – in one of the film’s most challenging revelations – we learn is unaware of the swap, and the situation later escalates when a wounded Luke leaks the truth. A wildly aggressive Brandon confronts Olivia, but his physical attack is impeded by a defensive Nat. He then screams, ‘Your little faggot friend fucking raped me last night,’ accusing Olivia of luring him into sex under false pretences. When Nat challenges, ‘Are you going to bash a girl?’ Brandon responds – again with shades of transphobia blurred by the speculative context and Olivia not identifying overtly as a trans woman – ‘That is no fucking girl. You think this is funny, Olly? I have to live with this for the rest of my life.’

Monks, who worked extensively on the long-gestating script with Cruz-Martin and his co-stars, does not shy away from this dilemma. The body-swap idea sprang from his 2010 short Herman and Marjorie, on which Cruz-Martin worked as cinematographer, in which a fifty-year marriage is transformed when a frail old man replaces his dying body with that of a much younger man. Originally, Pulse was to follow three separate body-swap scenarios, but Monks followed advice to home in on his personal experience:

As long as it was true to my journey, then I felt that – instead of trying to encompass all experiences, something I would never be able to do – the specificity of my own experience would be able to reach more people and feel more real.

Uncovering the mirror

For Monks, when he was at his lowest ebb and wishing to magic away both his disabled and queer identities, part of the problem was a very real lack of visibility.

I remember when I was about thirteen or fourteen, struggling with being gay and disabled, I felt so alone. And the things that made me feel less alone were watching gay short films on YouTube late at night, then clearing my ‘History’ afterwards so my parents wouldn’t see it […] There have been such huge strides in queer filmmaking, but the thing that I found, and a huge influence in making Pulse, was that I had never seen a film that spoke to what it was actually like to be a young person with disability and to struggle with it.

Corroborating this, a recent study conducted by Screen Australia, Seeing Ourselves: Reflections on Diversity in Australian TV Drama, found that disability is significantly underrepresented, at only 4 per cent of main characters featured in Australian television drama series aired from 2011 to 2015, as compared to around 18 per cent of the population.[2]Screen Australia, Seeing Ourselves: Reflections on Diversity in Australian TV Drama, 2016, available at <https://www.screenaustralia.gov.au/getmedia/157b05b4-255a-47b4-bd8b-9f715555fb44/TV-Drama-Diversity.pdf>, accessed 19 May 2017, p. 15. It is also the case that disabled parts are routinely played by able-bodied actors and that these stories are told by crews consisting solely of able-bodied writers and directors.[3]ibid., pp. 25–6, 28–32. The same report also found that representations of LGBTQI people failed to match population levels, at only 5 per cent compared to an estimated 11 per cent.[4]ibid., p. 17. Quoted in Seeing Ourselves, Monks says,

I feel passionately about this, not only because I’m a struggling actor with a disability, but also because the more disabled actors we have on our screens, the greater impact we can have on people with disabilities in our society […] If there had been more positive depictions of people with disability in the media when I acquired my disability as an 11 year old, I believe I wouldn’t have struggled with my self-worth as a disabled person as much.[5]Daniel Monks, quoted in ibid., p. 16.

Yet Cruz-Martin argues there’s also a universality to Pulse’s button-pushing set-up: ‘Hasn’t everyone questioned their body image at some point in their life?’ She adds that Olivia’s selfish and, at times, self-harming behaviour is recognisable to anyone who, like Monks, has struggled with their identity and feelings of self-worth. ‘This is what Olly thought he wanted so much, and that’s why [as Olivia] he goes down that rabbit hole for a while.’

Casting Olivia was crucial to Pulse’s success. Peasley’s performance picks up on the subtle tics of Monks’ Olly. During early test shots, Cruz-Martin had mirrored each scene with both Monks and Peasley, but eventually rejected that approach. ‘We made a decision that, whenever Olivia’s using her body and her sexuality, the camera’s on Jaimee, but whenever we’re feeling something and we’re in the psyche, we’re showing Dan.’

The physicality of Monks – who, these days, is also a professional dancer – is mesmeric, particularly in the fourth-wall-breaking final shot. Having made the momentous decision to return to his original body, a metaphor not just for acceptance but also clearing the pathway towards pride, Olly dances alone in his room before turning to the camera and smiling. You get the sense that things will turn out alright for him, much as they have for the wildly talented Monks, who has returned to performing with gusto. ‘It was three years into writing [Pulse] that I realised that this lead character was based on me; no-one could play him better.’

http://www.pulsefeaturefilm.com

Endnotes

| 1 | Daniel Monks, ‘The Accessibility of Acting’, The HubStudio website, 31 January 2017, <http://www.thehubstudio.com.au/the-accessibility-of-acting/>, accessed 19 May 2017. |

|---|---|

| 2 | Screen Australia, Seeing Ourselves: Reflections on Diversity in Australian TV Drama, 2016, available at <https://www.screenaustralia.gov.au/getmedia/157b05b4-255a-47b4-bd8b-9f715555fb44/TV-Drama-Diversity.pdf>, accessed 19 May 2017, p. 15. |

| 3 | ibid., pp. 25–6, 28–32. |

| 4 | ibid., p. 17. |

| 5 | Daniel Monks, quoted in ibid., p. 16. |