Roughly a quarter of the way into Mark Cousins’ fourteen-hour documentary Women Make Film: A New Road Movie Through Cinema (2018), the theme of discovery takes central focus. Juxtaposing a scene of a sweetly misguided childhood epiphany in So Yong Kim’s Treeless Mountain (2008) with that of a young boy’s uncovering of a living landscape of writhing naked female bodies in Lucile Hadžihalilović’s Evolution (2015) and Josh’s (Tom Hanks) shock revelation that he has become an adult overnight in Penny Marshall’s Big (1988), the film turns to a scene that actress Tilda Swinton’s voiceover narration promises will engender ‘seeing with new eyes’. At first blush, the single shot of pioneer filmmaker Alice Guy-Blaché’s short film Avenue de l’opéra (1900) could be dismissed as a primitive example of early cinema or a historical fragment of fin de siècle Paris – that is, until the viewer registers that everything within the frame (the horse-drawn carriages, the cyclists and the gentlemen strollers) is travelling backwards. In setting her view of the avenue in reverse, Guy-Blaché not only plays a trick on the viewer’s perception, but also underscores the power of cinema to unravel conventional modes of seeing. This disruption of both linear time and the simple act of looking in Avenue de l’opéra anticipates the revisionist approach to film history taken in Women Make Film, in which Cousins implores the viewer to experience a cinematic double take.

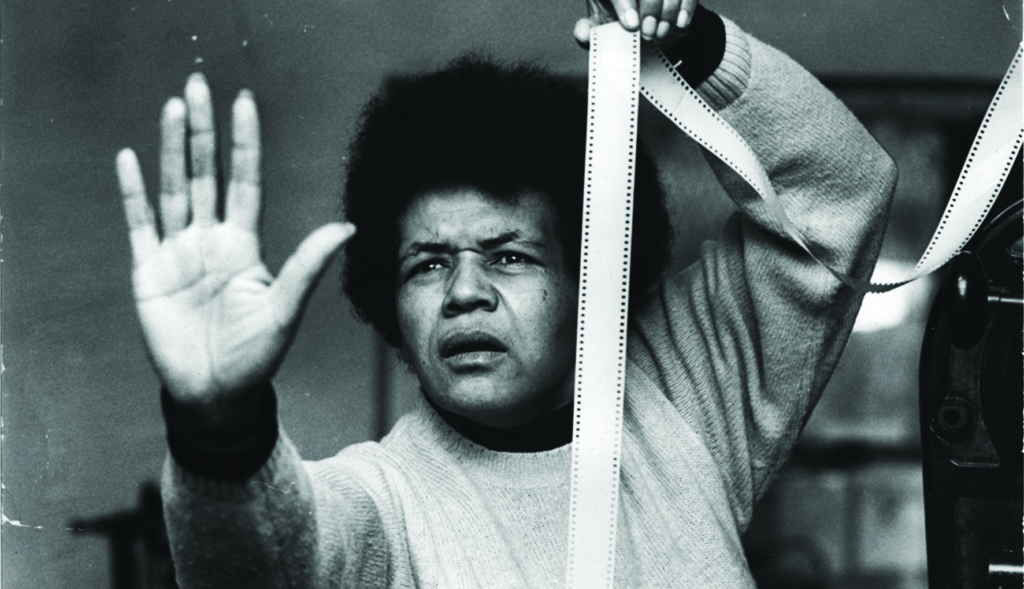

A companion piece to Cousins’ fifteen-hour ‘global road movie’ The Story of Film: An Odyssey (2011), Women Make Film similarly utilises the trope of the road movie as a structuring device. However, while The Story of Film pursues an itinerary that takes the viewer beyond the limited geography of Hollywood, Women Make Film follows a gendered map. Organised into forty chapters that focus on select themes, genres and conventions, the documentary examines topics as diverse as sex, the meaning of life, melodrama, song and dance, editing, and close-ups – all through the lens of female filmmakers. To counter arguably myopic cultural perceptions of the contribution of women to the craft, Cousins employs over 500 scenes from filmmakers whose work has often been relegated to the footnotes of film history. Indeed, it is the director’s explicit intention that Women Make Film function as a corrective, as expressed in a statement that accompanied the documentary’s premiere at the 2018 Venice Film Festival:

Many films about cinema feature only male directors, so this one is a [riposte]. It is a film school, where all the teachers are female. There is much ignorance and blindness about women directing film. Our film boldly challenges this blindness.[1]Mark Cousins, ‘Director’s Statement’, in ‘Women Make Film: A New Road Movie Through Cinema’, La Biennale di Venezia website, <https://www.labiennale.org/en/cinema/2018/lineup/venice-classics/women-make-film-new-road-movie-through-cinema>, accessed 2 August 2021.

Although Swinton informs the viewer early in the documentary that both the film industry – ‘a boys’ club’ – and film history are ‘sexist by omission’, Women Make Film is less concerned with putting forward a feminist agenda than asking what Cousins has referred to as ‘ahistorical questions’.[2]Mark Cousins, in ‘BFI at Home: Women Make Film Q&A with Director Mark Cousins, 21/05/2020 19:00 BST’, YouTube, 22 May 2020, <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SVjEerD7wGc>, accessed 2 August 2021. Although the documentary’s release fortuitously coincided with the global rise of the #MeToo movement, Cousins began working on his opus five years beforehand, and he doesn’t use the marginalisation of the work of the female directors featured as a key conceit. Rather, Cousins uses the film to frame a number of cinematic questions and propositions that are not specific to either the gender of the filmmakers or the period in which the documentary was researched and edited. True to his statement that Women Make Film is a ‘film school’, Cousins proposes questions over the course of its running time that are deeply poignant for all films, regardless of the gender of the director. Some of these lines of interrogation encompass ‘How do worlds unfurl in films?’, ‘How do good filmmakers do revelations?’ and ‘What happens when filmmakers purposefully leave things out of their shot or story?’

Joining Swinton in voicing these broader questions is an impressive collective of international actresses, comprising Jane Fonda, Adjoa Andoh, Sharmila Tagore, Kerry Fox, Thandiwe Newton and Debra Winger. Although Cousins wrote the script for Women Make Film, the strategic choice for his words to be narrated by a chorus of female voices reveals a multiplicity of experiences through the narrators’ individual accents, speaking rhythms and intonations, and this complements the expansive journey the documentary undertakes across six continents and 130 years of cinema. As the gatekeepers of Women Make Film’s so-called ‘academy of Venus’, the narration of Swinton et al. brings Cousins’ film essay to life in a tone that is more intimately conversational in its spirit of inquiry than strictly pedagogical. Fox remarks in voiceover that ‘men have mostly controlled the lens and what it looks at and how it looks’, but here our narrators take the reins. Collectively, they gently draw the viewer’s eye to covert details in visual sequences; on some occasions they contextualise what the viewer is watching and, on others, allow the viewer to make their own conclusions; and, most significantly, they reposition the work of female filmmakers within the narrowly defined and gendered boundaries of film history.

On the road: Deconstructing genre conventions

Cousins opens Women Make Film with the dim view of a cobbled street from Binka Zhelyazkova’s We Were Young (1961). The scene unfolds during a blackout in World War II as a single beam of torchlight illuminates the stones of the dark path. Although Swinton’s voiceover notes that Zhelyazkova’s film is ‘almost unknown’ and therefore an appropriate place from which to begin Cousins’ mission to readdress the film canon, the scene also visually enacts the first tentative steps down a path out of darkness towards a new way of viewing cinema. Opening with the travelling shot from We Were Young anticipates the act of journeying that serves as a thematic thread for the subsequent fourteen hours of the film. From these first moments on foot, the motif of the journey in Women Make Film reappears in unexpected ways. For example, in the ‘Openings’ chapter, the viewer descends into a subterranean tunnel in Hadžihalilović’s Innocence (2004) that evokes the ‘subconscious’, before, in the ‘Editing’ chapter, carving through the ocean on a sailing boat in Leni Riefenstahl’s Olympia Part Two: Festival of Beauty (1938). Later, in the ‘Comedy’ chapter, the viewer is dragged backwards through the streets of New York while trapped in a phone booth in Marshall’s Jumpin’ Jack Flash (1986); and, as part of the ‘Memory’ chapter, is subsequently transported through the hazy interstices of recollection via the magic of a soft dissolve in Maria Plyta’s The She–Wolf (1951). Whether evoking movement from place to place, through time or into a realm of dreams, Women Make Film endeavours to follow an itinerary that places the viewer in a constant state of motion.

As Women Make Film transitions between different chapters and narrators, the documentary continually returns to travelling shots that move through different seasons, geographies and landscapes. In most cases, the viewer is positioned in the front passenger seat of a car that interchangeably travels on empty nocturnal highways, through quaint villages and bustling cityscapes, down tree-lined suburban streets, and along mountainous vistas shrouded in mist. A cynical reading of these travelling shots might be that they simply provide the connective thread that stitches together the documentary’s mosaicking of film scenes and multiple narrations. However, that would overlook Cousins’ explicit positioning of Women Make Film as ‘a new road movie through cinema’. Although neither the featured films nor the directors are new in and of themselves, the manner in which the documentary intervenes into the conventionally male space of the road movie genre constitutes a fresh approach.

Historically dominated by films such as Dennis Hopper’s Easy Rider (1969) and Monte Hellman’s Two–Lane Blacktop (1971), the road movie is traditionally the projection of a ‘male escapist fantasy’ arising from ‘the breakdown of the family unit [… that] so witnesses the resulting destabilization of male subjectivity and masculine empowerment’.[3]Steven Cohan & Ina Rae Hark, ‘Introduction’, in Cohan & Hark (eds,), The Road Movie Book, Routledge, London & New York, 1997, pp. 2, 3. Notably, the exclusion of women from the narratives of the genre has also extended behind the camera, with even notable films that reverse or play with the masculine codes of the road movie such as Thelma & Louise (Ridley Scott, 1991) and The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert (Stephan Elliott, 1994) being the product of male direction. By framing Women Make Film as a road movie, Cousins not only reinforces the motif of journeying, but also interrogates the manner in which cinema is silently gendered by re-creating a road movie through fragments of films made by women.

This gendering extends to concepts as fundamental as the way films are described and what aspects of life are considered cinematic. Early in the documentary, in reference to a scene from Kira Muratova’s Brief Encounters (1967) that resembles the later work of David Lynch, Swinton asks, ‘But why do we have to use the word “Lynchian”? Why don’t movie lovers call something like this “Muratovan”?’ Notwithstanding the relative obscurity of Muratova and her work within wider film discourse, Women Make Film reveals how the language used to refer to cinema has failed to integrate references to the female auteurs who have contributed to the craft. And when the documentary turns to the theme of work, Fonda’s voiceover, which accompanies the bed-making scene from Chantal Akerman’s Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975), draws attention to how film imagery is privileged according to how it can be perceived through the prism of gender:

Akerman is after something more radical. She said that, in movies, there were hierarchies of images: a kiss or a car crash was more important than domestic work. She wanted to level the hierarchy, to respect this work, this world making and remaking.

In other words, Akerman is in this scene actively inscribing the seemingly banal, and therefore neglected, actions of femininity into a space prescribed by masculine notions of entertainment.’

Although the highly masculine context of road movies may at first appear to be at odds with the feminine focus of Women Make Film, it is, in fact, an entirely appropriate genre due to the mode of escape that it engenders. Richard Ingersoll writes that road movies allow ‘[film] characters to enjoy the liminal status of provisional freedom from the formal or moral constraints of urban situations’;[4]Richard Ingersoll, Sprawltown: Looking for the City on Its Edges, Princeton Architectural Press, New York, 2006, p. 96. and, here, Cousins is similarly appropriating the car as a space of possibility to travel a route as yet unwritten on the cinematic map. The alternative cartography traced in Women Make Film is particularly realised in what is arguably the documentary’s most evocative genre chapter: ‘Horror and Hell’. With the exception of the feminist vampire protagonist in Ana Lily Amirpour’s A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night (2014), the cheap supernatural thrills often associated with the horror genre’s reliance on malevolent otherworldly figures, blood and the incursion of nightmares in everyday reality are notably absent. As Newton pronounces, ‘This chapter was intended to be about the horror genre, but it’s sliding towards real-life horror: […] the hell of abuse, murder, torture, war and homelessness.’ What remains unspoken but is nonetheless conveyed through the succession of these film scenes is that female directors take unusual and innovative approaches to genre conventions. For the filmmakers featured in this chapter, there seems to be more psychological fear and repulsion evoked in phenomena such as the ‘muted beige and heritage greens, soft furnishings and tasteful art’ in Joanna Hogg’s Archipelago (2010) than in the uncanny presence of the undead. Through directions such as these, the road that Cousins takes the viewer down revels in the unexpected.

Intertextual gestures and uncovering the visual imagination

Cousins employs the road movie genre to not only deconstruct established cinematic codes, but also underscore the intertextual journeys that take place between films. In the chapter titled ‘Journey’, Cousins uses the surprising juxtaposition of Guy-Blaché’s Course à la saucisse (1907) and Kathryn Bigelow’s Point Break (1991) to demonstrate the manner in which films maintain visual dialogues across time and space. On the surface, Guy-Blaché’s film, which involves a group of villagers running after a dog that has absconded with a string of sausages, has little in common with Bigelow’s crime thriller. However, the reference to the chase sequence and its accompanying obstacles from Course à la saucisse in Point Break’s dynamic scene of pursuit stresses how female directors have laid the foundation for visual vocabularies that are traditionally stamped as male.

Another way in which Women Make Film subverts the expectations of the road movie is by replacing the genre’s masculinist escape with feminine remembrance. This is most poetically realised in the documentary’s closing moments, in which sepia-toned and black-and-white still portraits of some of the featured filmmakers are displayed before its final destination, the Maryrest Cemetery in New Jersey, is reached. As the handheld camera shakily pans down to Guy-Blaché’s gravestone – the inscription on which is almost obscured by the sunlight reflected on the grave’s surface – the viewer is reminded, by contrast, of the darkness of We Were Young that opened the documentary. However, while Swinton guides the viewer on how to read Zhelyazkova’s film, this final moment contains no narration, requiring the viewer to decipher the meaning for themselves by being attentive to the details of the image.

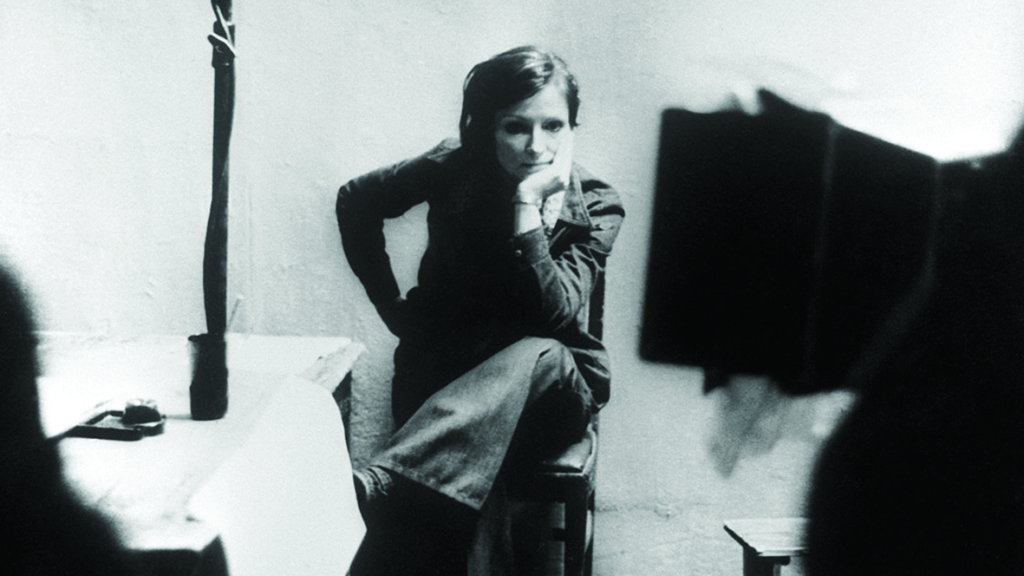

These tools of visual attention are previously foregrounded in the chapter on ‘Framing’ via the cafe scene in Agnès Varda’s Le Bonheur (1965), in which the camera fragments the space surrounding the characters and pulls the focus away from their conversation and interactions. Using Le Bonheur as an example, Swinton explains that ‘a film doesn’t need to be story, action or psychology. It can be its own shape – a series of spaces like a building is a series of spaces, which is adjacent to the story.’ Although the combined effects of the editing and framing in Le Bonheur emphasise the distracted glances bound up with the characters’ flirtation, they also accentuate how meaning can be created on the periphery of the frame. In addressing his self-imposed question of ‘How did the visual imagination of this great artist work?’ when considering each filmmaker’s scenes in Women Make Film, Cousins emphasises that, above all, the image is paramount. This is subtly reinforced through his decision to not include subtitles in these excerpts. With no recourse to dialogue, the viewer is encouraged to make sense of the films’ respective visual textures: for example, although a non-Swedish-speaking viewer does not have access to the actual dialogue in a scene taken from Mai Zetterling’s Loving Couples (1964), the beautifully choreographed dance of the camera as it stays a few steps ahead of the characters carries sufficient meaning in the way it gestures towards the push and pull of their intimacy.

Cousins’ frame-by-frame dissection of scenes in Women Make Film is arguably concerned with not only the cinematic effects created through the construction of cinema’s architecture – its cinematography and sound design – but also the impact on the viewer. One section of Andoh’s voiceover, which reflects on the frenetic cutting of the bar shootout that concludes Bigelow and Monty Montgomery’s The Loveless (1981), draws together these ideas: ‘The editing isn’t creating a single action, nor a metaphor, nor space, exactly. Instead, it’s creating sensations in our heads: confusion, excitement, flooding.’ Here, the physical movement of the camera and the dizziness of the editing contribute to the viewer being moved emotionally.

Indeed, among the many lines of inquiry in the documentary, what is consistently foregrounded is the dual movement of cinema as both motion and emotion. Notwithstanding the visual poetry that Women Make Film assembles during its fourteen-hour running time, Cousins’ documentary has a serious aim. As he commented in an interview with the British Film Institute, ‘Canons always need to be smashed […] We have to change every single film course that doesn’t teach large numbers of women.’[5]Mark Cousins, in ‘Women Make Film Q&A’, op. cit. Women Make Film does not seek to undermine the highly masculine lineage of cinema; rather, it proposes an alternative journey and framework for cinematic spectatorship. As Swinton beautifully contemplates, ‘There’s so much to find, to see, with new eyes.’

Endnotes

| 1 | Mark Cousins, ‘Director’s Statement’, in ‘Women Make Film: A New Road Movie Through Cinema’, La Biennale di Venezia website, <https://www.labiennale.org/en/cinema/2018/lineup/venice-classics/women-make-film-new-road-movie-through-cinema>, accessed 2 August 2021. |

|---|---|

| 2 | Mark Cousins, in ‘BFI at Home: Women Make Film Q&A with Director Mark Cousins, 21/05/2020 19:00 BST’, YouTube, 22 May 2020, <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SVjEerD7wGc>, accessed 2 August 2021. |

| 3 | Steven Cohan & Ina Rae Hark, ‘Introduction’, in Cohan & Hark (eds,), The Road Movie Book, Routledge, London & New York, 1997, pp. 2, 3. |

| 4 | Richard Ingersoll, Sprawltown: Looking for the City on Its Edges, Princeton Architectural Press, New York, 2006, p. 96. |

| 5 | Mark Cousins, in ‘Women Make Film Q&A’, op. cit. |