The original aim of the essays in Metro’s National Film and Sound Archive of Australia (NFSA) series was to provide definitive accounts of Australian films that were important during the ‘revival’ of the 1970s and 1980s, but it has now gone well beyond any such parameter. The series was set in train after Kodak and Atlab issued remastered prints of the films in the early 2000s; since its beginnings in Metro 152, forty-four titles have been explored to date. The standard of the essays has been consistently high: thorough in research, written in prose that makes them accessible to a wide readership and providing a first port of call for anyone wanting to pursue any of the films discussed or the work of their makers.

As editor of the series, I only required that each piece cover production history, an examination of the film text itself and the reception of the film by the public and critics. How the individual authors went about approaching these matters was up to them, and the result has been a pleasing variety of methods and attitudes. Some have been concerned with situating their film in the broader context of Australian filmmaking of the period; others, in the context of the director’s filmography.

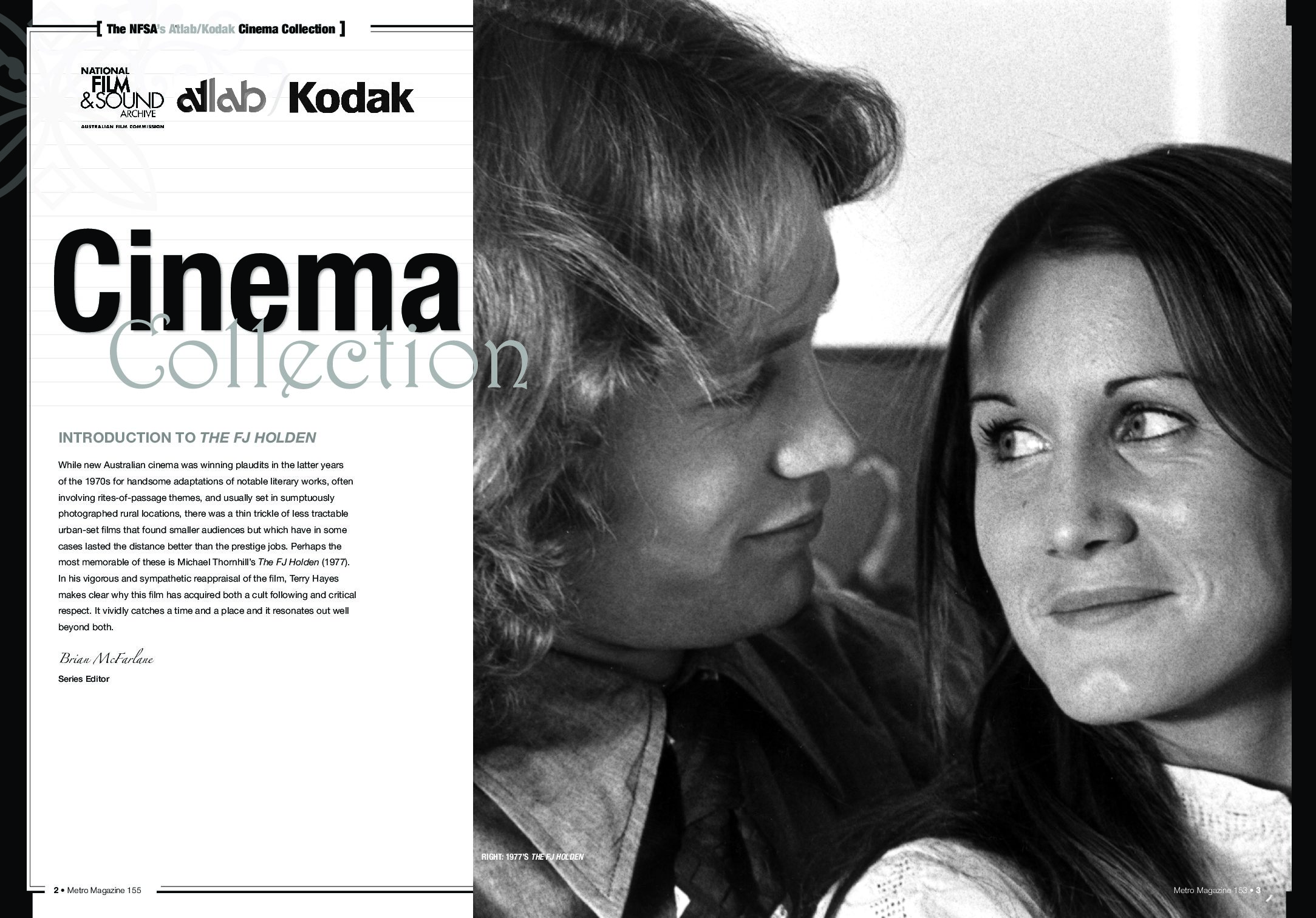

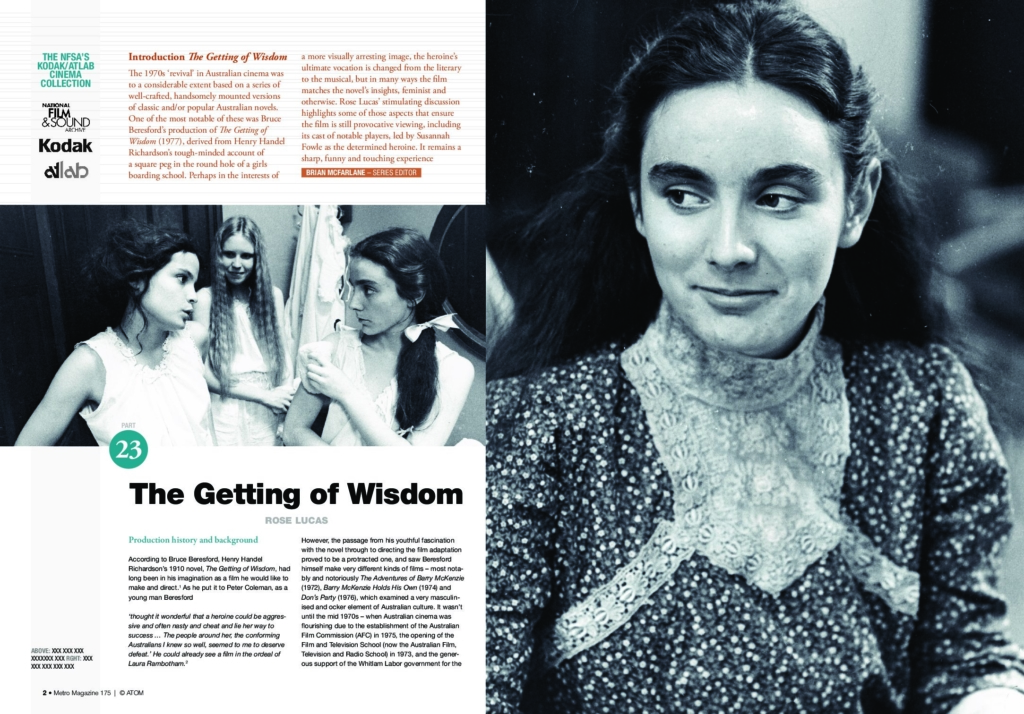

The range of films chosen reflects some of the main trends of the originally designated period. One of the rare films to date outside the 1970s and 1980s was Charles Chauvel’s Jedda (1955; M184) – on many counts one of Australia’s most significant films. Indeed, an overall objective for the series was that of striking a balance between the obviously key films, whether from commercial or critical viewpoints, and those that appeared to cry out for resuscitation, films that seemed to have fallen out of the public memory. In this respect, one might draw a contrast between Crocodile Dundee (Peter Faiman, 1986; M185), still perhaps the most popular Australian film, and Night Cries: A Rural Tragedy (Tracey Moffatt, 1990; M183), a valuable study of aspects of Indigenous cultures but by no means as widely seen as it might have deserved. Again, while the prestigious literary adaptations were commanding critical attention in the first decade of the revival – and thus we have a study of The Getting of Wisdom (Bruce Beresford, 1977; M175) – there have also been essays on genre pieces like the thriller Money Movers (Beresford, 1978; M161) and social-realist studies of urban lives as in The FJ Holden (Michael Thornhill, 1977; M155).

I wanted to see some of the well-known films of the period reappraised, so came an essay on Sunday Too Far Away (Ken Hannam, 1975; M158), a crucial title in the business of getting the New Australian Cinema moving. As well, though, it was felt salutary to bring to light again films that, while being very much of their time, seemed to have slipped out of sight – hence the essays on Mad Dog Morgan (Philippe Mora, 1976; M164) or Pure Shit (Bert Deling, 1975; M165). How would these titles survive critical scrutiny thirty-odd years on? And what about the ‘surfing film’ phenomenon: would films such as Crystal Voyager (David Elfick, 1973; M182) prove to have claims on attention for viewers other than the zealots of the waves?

The kind of research that has gone into each of the essays is important in placing the films in a variety of contexts: historical, generic and industrial, for instance. ‘Historical’ can refer not just to how the film belonged to the period of its making, but also to what it may have meant in terms of, say, a director’s career. As to ‘generic’, these noteworthy Australian works tackled a wider range of film types than might have seemed the case at the time when the big prestige titles (such as Peter Weir’s 1975 Picnic at Hanging Rock; M35, M149, M193) were more apt to be regarded as works sui generis, so it seemed important to investigate again what made a heist thriller such as Money Movers work – or an action-adventure like The Man from Hong Kong (Brian Trenchard-Smith, 1975; M180) or a war film like The Odd Angry Shot (Tom Jeffrey, 1979; M156). By ‘industrial’, I refer to the kinds of problems, obstacles and encouragement that lay behind getting this or that film not just onto the screen, but onto the sound stage – or wherever filming began. It always has to be remembered that film is not just art; it is an industrial product as well, and one of the strengths of the essays in this series lies in how they suggest the interweaving of these two disparate strands of influence.

As series editor, I have been grateful to the film scholars and critics who have been responsible for maintaining the collection’s high standard of analysis and readability. Film is a popular artform, and there needs to be some writing about it that takes this into account so that it is made accessible to a reading public beyond those who are already steeped in screen culture. In bringing famous films to new appraisal or bringing less famous ones to light again several decades later, the series has offered the pleasures of recognition or of new insight for anyone who is interested in Australian cinema from whatever stance, whether as film scholar or film enthusiast.