Prior to launching into its narrative, Alex Siddons’ documentary The Art of Incarceration (2019[1]Although initially premiering in 2019, The Art of Incarceration, like many other films, had its full release potential impeded by COVID-19. It has since been relaunched with a screening at the Gold Coast Film Festival in April 2021, and also played in the online program of Tasmania’s Breath of Fresh Air Film Festival the following month.) presents some sobering statistics: 27 per cent of adults in Australian prisons and a startling 55 per cent of youth in custody are of Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander background, and 58 per cent of Indigenous offenders return to jail within a year of release. Likewise, a young Indigenous man is statistically more likely to go to prison than university, and Indigenous Australians are per capita the most incarcerated people on the planet.[2]These disparities are directly referenced in the film. See also The Art of Incarceration official website, <https://www.theartofincarceration.com>; and Thalia Anthony, ‘FactCheck Q&A: Are Indigenous Australians the Most Incarcerated People on Earth’, The Conversation, 6 June 2017, <https://theconversation.com/factcheck-qanda-are-indigenous-australians-the-most-incarcerated-people-on-earth-78528>, both accessed 13 May 2021. In voiceover, the film’s narrator, Bunurong Wiradjuri actor, activist and elder Uncle Jack Charles, further outlines the inequalities and generational trauma that so dramatically increase the prospect of incarceration. In taking its time to set up this sociohistorical context first, the film signals that we are not necessarily just going to see a story of art triumphing over prison life: although there are moments of great joy and redemption to come, we must also be prepared to take on board the circumstances that brought these men into the system, and that often keep them there for a large portion of their lives. In the words of the film’s publicity materials, the documentary ‘both analyses and humanises the over representation of Indigenous Australians within the prison system’.[3]‘The Story’, The Art of Incarceration official website, <https://www.theartofincarceration.com/synopsis.html>, accessed 13 May 2021.

Siddons’ film follows a number of inmates and ex-prisoners of Victoria’s correctional system. Inmates are shown preparing artworks for an exhibition entitled Confined – an annual event organised by The Torch, a not-for-profit which has been delivering the Statewide Indigenous Arts in Prison and Community (SIAPC) program since 2011 (The latest instalment, Confined 12, launched in May 2021). The program – spearheaded in the state’s prison system and Victoria’s North West community respectively by Indigenous arts officers Paul McCann and Robby Wirramanda – is underpinned by ‘the role of culture and cultural identity in the rehabilitative process of Indigenous prisoners’,[4]‘What We Do’, The Torch website, <https://thetorch.org.au/what-we-do/>, accessed 13 May 2021. and The Art of Incarceration explores how it addresses a number of key challenges for incarcerated Indigenous people, such as separation from cultural identity, family and community. Devoting much of its screen time to three particular men involved at either end of the SIAPC program, the film demonstrates how the program both offers participants a sense of self-worth and goes some way to helping restore the confidence of those whose lives have been broken in so many ways.

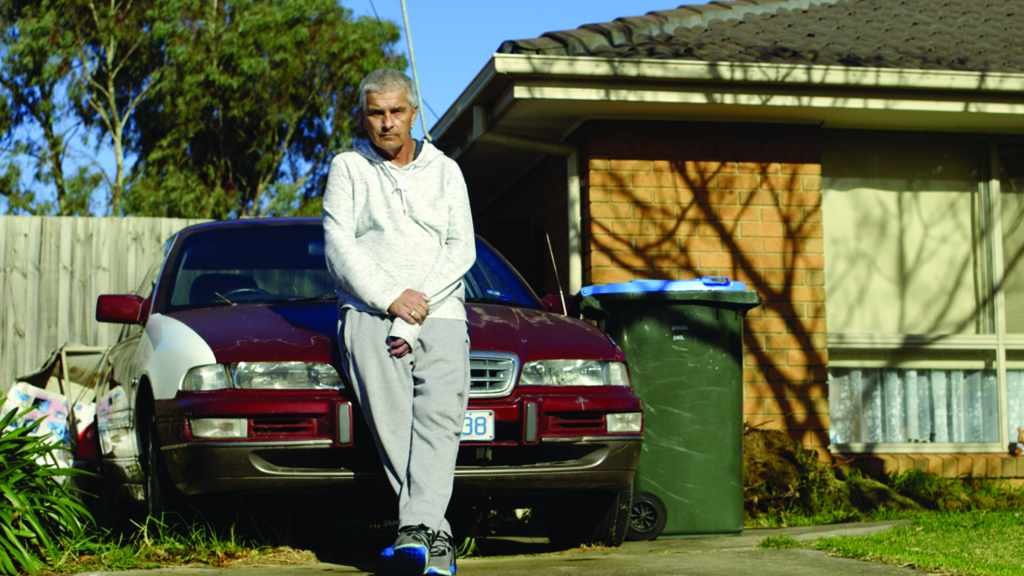

Given the relationship between personal identity and culture is so inextricably linked, one of the aims of The Torch – as reiterated by the organisation’s CEO, Barkindji artist and curator Kent Morris, whose own early life was marked by cultural estrangement – is for prisoners undertaking the program to learn more about all aspects of their culture.[5]Jake Watt, ‘The Art Of Incarceration: A Portrait of Culture and Identity’, SWITCH, 26 July 2019, <https://www.maketheswitch.com.au/article/review-the-art-of-incarceration-a-portrait-of-culture-and-identity>, accessed 13 May 2021. Early in the film, Charles states that art is ‘one of the most [pure] and accessible ways [for] our people to connect with culture’, but also ponders how effectively that connection can be made behind bars. For one of The Art of Incarceration’s central figures, Wembawemba man Troy Brabham, the answer is in the affirmative: recounting having felt a strong connection to his roots as a child, Brabham says that, through the program, he was able to explore ways of reconnecting his personal identity with his culture by ‘stepping back and looking at [himself]’, and, accordingly, come to terms with the addiction and violence of his past. Following a longstanding period of self-loathing, he says, being able to express himself through art ‘lit a fire of inspiration’ under him. While painting is clearly a highly introspective and cathartic process for Brabham, he says he is most grateful for the chance to offer his art ‘as a gift to the universe’. Later in the film, we see that he has been released from prison and has continued to paint. He is determined not to go back inside, and it seems his artwork – along with his move to a rural location – has allowed him to reconnect with country, self and culture. Sadly, Brabham soon succumbs to the demons of his past, and we learn that he died of a suspected drug overdose not long after filming – a revelation made all the more poignant by the touching speech we see him give about his personal redemption post-incarceration: ‘Things do get better. Like a phoenix from the ashes, you can rise.’

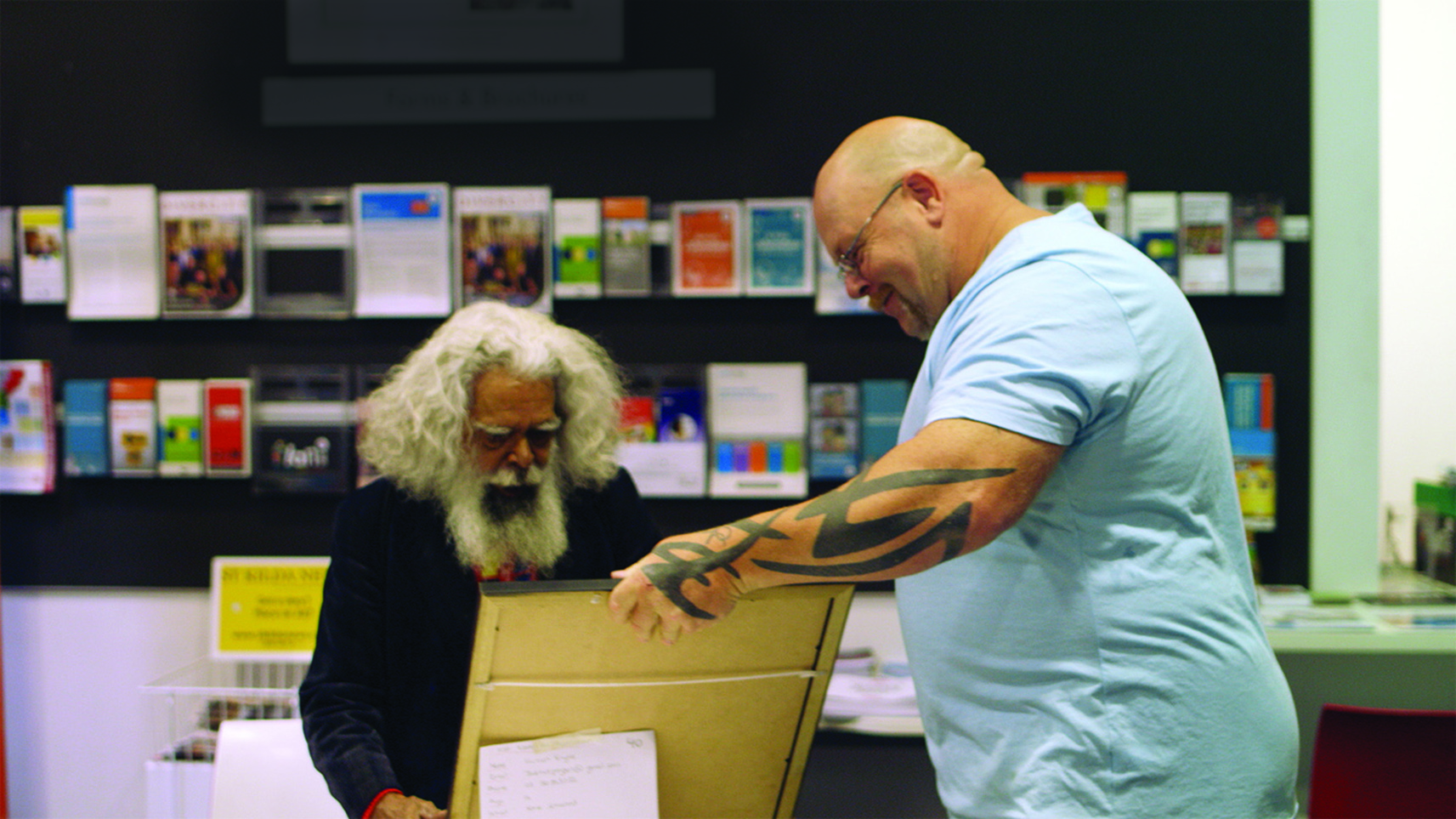

The second major protagonist of the documentary, Gunditjmara Keerraaywoorrong man Christopher Austin, has a tragic backstory of incarceration and institutionalisation spanning almost four decades. Although he mentions that he has always painted, his participation in the program allows him to further develop his artistic process. He is very upfront about the redemptive power of art – he feels that it gives inmates a ‘new direction’, and, in his own case, recognises how the program is helping to free him from the ‘roundabout’ of addiction and reoffending that has marred his life. Although Austin has been in and out of correctional facilities for so many years, when we see him on parole with his family (including his young daughter), he imparts that this time things feel different, and that he is determined to stay out of prison. It is inspiring to see Austin achieve one of The Torch’s other aims – economic security after release through the sale of his art[6]According to the organisation, 100 per cent of the sale price of artworks featured in exhibitions and on The Torch’s website goes to artists. See ‘Support Us’, The Torch website, <https://thetorch.org.au/support-us/>, accessed 13 May 2021. – and the moment in which he gets to walk into the gallery as a free man and see the artworks being prepared for Confined 9 is one of the most touching in the film. While he is pleased to now be able to provide an honest income for his family – previously, he says, all he knew in terms of earning money involved crime – he outlines that this newfound capacity is not so much about the money itself as about fostering a sense of self-worth. Near the end of the film, when Charles reveals his own history of incarceration – a period of which he shared with Austin – he asks, ‘Who would have thought we would survive to tell our story?’ Austin is a true survivor, aptly described by reviewer Jake Watt as ‘the gentle, philosophical heart’ of the film.[7]Watt, op. cit.

The documentary’s third narrative, the story of Wergaia ex-convict Wirramanda, takes us out of the prison system and into the heart of family, country and community. Like many other current or former prisoners, he got involved in crime from an early age, which inevitably led to a stint inside. His grandmother fostered a love of art and culture in him from a young age, and this is something he later reconnected with while in prison. We first meet Wirramanda, now on parole, as he is assembling a large sculptural installation on the dry bed of Lake Tyrrell – in his grandmother’s country – with the help of his sons. Wirramanda is employed by The Torch as a regional arts adviser, and is the first former participant to have been given such a role. In his work with other ex-prisoners in the community, he doesn’t just focus on mentoring them as artists, but also builds trust and kinship through other bonding activities such as fishing and socialising with their families. At the fishing spot, he uses the river as an analogy for his life of crime and redemption: he says that, in order to solve your problems, you need to dive into them, and – as he did for himself – face the ‘pivotal points in [your] life’ rather than run from them. Wirramanda’s positive relationship with his sons, along with his obvious desire to be a better father and mentor to them, provides hope for the next generation to break the cycle of crime and imprisonment. He is revealed to be not only a talented artist, but also an accomplished singer/songwriter: the film ends with moving portraits of the key characters accompanied by Wirramanda performing his original song ‘Coming Home, Again’.

The sheer number of Indigenous people in prisons ensures that the effects of incarceration inevitably touch so many families, directly or indirectly.

This year’s thirtieth anniversary of the delivery of the final findings of the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody serves as a grim reminder that many of the structural failings underpinning these men’s stories – and those of so many others – are yet to be rectified. Over 470 Indigenous people have died in police custody since that report was published, a fact ALP senator Patrick Dodson, himself a Yawuru man, rightly brands a ‘national shame’.[8]Patrick Dodson, quoted in Lorena Allam et al., ‘The 474 Deaths Inside: Tragic Toll of Indigenous Deaths in Custody Revealed’, The Guardian, 9 April 2021, <https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2021/apr/09/the-474-deaths-inside-rising-number-of-indigenous-deaths-in-custody-revealed>, accessed 13 May 2021. Although the film does not not specifically focus on deaths in custody, the subject is touched on at one point when Morris learns during a visit that a cousin of his has died in prison. This also reinforces the familial and community connections mentioned throughout the film – many of those interviewed have family members who are currently or have previously been incarcerated. Indigenous arts officer McCann identifies one of the men in the prison program as his cousin; Wirramanda and Brabham are also revealed to be cousins. Wirramanda reiterates that spending time inside often brings home the reality of premature death for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people; it is all too common to find, upon leaving prison, that a number of lives have been lost in your family while you were serving time. The sheer number of Indigenous people in prisons ensures that the effects of incarceration inevitably touch so many families, directly or indirectly.

The Art of Incarceration calls to mind two other excellent local documentaries about artistic expression in prison settings: Prison Songs (Kelrick Martin, 2015) and Kings of Baxter (Jack Yabsley, 2017). The former – dubbed ‘Australia’s first documentary musical’[9]Victoria Laurie, ‘SBS Documentary Prison Songs Tells Inmates’ Tales in Their Own Words’, The Australian, 1 January 2015, <https://www.theaustralian.com.au/arts/television/sbs-documentary-prison-songs-tells-inmates-tales-in-their-own-words/news-story/f75d1fa01af037f3ea4c747079cd573a>, accessed 13 May 2021. – depicts inmates of Darwin’s Berrimah prison; the latter focuses on the largely Indigenous population at New South Wales’ Frank Baxter Youth Justice Centre as they work with professional actors on a production of Shakespeare’s Macbeth. All three films provide rare access to the Australian prison system and, while ultimately uplifting, throw a necessarily uncomfortable light on the reality and complexities of Indigenous incarceration. As an editorial in The Sydney Morning Herald has pointed out, dismissal of these complexities, ‘which include systematic bias in the criminal justice system’, is part of the reason why such high rates of incarceration and deaths in custody persist.[10]‘High Time to Confront the Epidemic of Black Deaths in Custody’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 13 April 2021, <https://www.smh.com.au/politics/nsw/high-time-to-confront-the-epidemic-of-black-deaths-in-custody-20210413-p57iwm.html>, accessed 13 May 2021.

Within these stories, sorrow and redemption walk hand in hand; for every person we see rising above their circumstances, there are many others who cannot. In The Art of Incarceration, Charles justifiably labels current rates of Indigenous imprisonment a ‘national crisis’. Films such as these are vital in depicting the people behind the statistics, as well as the redemptive role art can play in connecting with self, culture, family and community.

https://theartofincarceration.com/

Endnotes

| 1 | Although initially premiering in 2019, The Art of Incarceration, like many other films, had its full release potential impeded by COVID-19. It has since been relaunched with a screening at the Gold Coast Film Festival in April 2021, and also played in the online program of Tasmania’s Breath of Fresh Air Film Festival the following month. |

|---|---|

| 2 | These disparities are directly referenced in the film. See also The Art of Incarceration official website, <https://www.theartofincarceration.com>; and Thalia Anthony, ‘FactCheck Q&A: Are Indigenous Australians the Most Incarcerated People on Earth’, The Conversation, 6 June 2017, <https://theconversation.com/factcheck-qanda-are-indigenous-australians-the-most-incarcerated-people-on-earth-78528>, both accessed 13 May 2021. |

| 3 | ‘The Story’, The Art of Incarceration official website, <https://www.theartofincarceration.com/synopsis.html>, accessed 13 May 2021. |

| 4 | ‘What We Do’, The Torch website, <https://thetorch.org.au/what-we-do/>, accessed 13 May 2021. |

| 5 | Jake Watt, ‘The Art Of Incarceration: A Portrait of Culture and Identity’, SWITCH, 26 July 2019, <https://www.maketheswitch.com.au/article/review-the-art-of-incarceration-a-portrait-of-culture-and-identity>, accessed 13 May 2021. |

| 6 | According to the organisation, 100 per cent of the sale price of artworks featured in exhibitions and on The Torch’s website goes to artists. See ‘Support Us’, The Torch website, <https://thetorch.org.au/support-us/>, accessed 13 May 2021. |

| 7 | Watt, op. cit. |

| 8 | Patrick Dodson, quoted in Lorena Allam et al., ‘The 474 Deaths Inside: Tragic Toll of Indigenous Deaths in Custody Revealed’, The Guardian, 9 April 2021, <https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2021/apr/09/the-474-deaths-inside-rising-number-of-indigenous-deaths-in-custody-revealed>, accessed 13 May 2021. |

| 9 | Victoria Laurie, ‘SBS Documentary Prison Songs Tells Inmates’ Tales in Their Own Words’, The Australian, 1 January 2015, <https://www.theaustralian.com.au/arts/television/sbs-documentary-prison-songs-tells-inmates-tales-in-their-own-words/news-story/f75d1fa01af037f3ea4c747079cd573a>, accessed 13 May 2021. |

| 10 | ‘High Time to Confront the Epidemic of Black Deaths in Custody’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 13 April 2021, <https://www.smh.com.au/politics/nsw/high-time-to-confront-the-epidemic-of-black-deaths-in-custody-20210413-p57iwm.html>, accessed 13 May 2021. |