How important is coming first? The question is everywhere when I chat to Yorta Yorta artist Tiriki Onus, co-director of Ablaze (2021). For one thing, one of history’s most surreal Olympic Games has just kicked off.[1]See Andy Bull, ‘Surreal Spectacle of a Superbly Set Up Olympics with No One Here to Enjoy It’, The Observer, 24 July 2021, <https://www.theguardian.com/sport/2021/jul/24/surreal-spectacle-of-a-superbly-set-up-olympics-with-no-one-here-to-enjoy-it>, accessed 9 August 2021. And, in the nightly news, there is Prime Minister Scott Morrison skilfully backflipping away from his earlier public assertion that Australia’s vaccination drive was ‘not a race’.[2]See Josh Taylor, ‘From “It’s Not a Race” to “Go for Gold”: How Scott Morrison Pivoted on Australia’s Covid Vaccine Rollout’, The Guardian, 29 July 2021, <https://www.theguardian.com/society/2021/jul/29/from-its-not-a-race-to-go-for-gold-how-scott-morrison-pivoted-on-australias-covid-vaccine-rollout>, accessed 9 August 2021. But then, governments rewriting history to suit their own purposes is no new phenomenon in Australia, a fact that emerges as a key theme of this rousing documentary, which unearths the important story – one oft deliberately obscured by the powers that be – of his grandfather William ‘Bill’ Onus.

The ‘first’ question pops up regarding a lost fragment of Bill’s own documentary work from 1946, which was discovered in the National Film and Sound Archive of Australia (NFSA) and brought to his grandson’s attention by historian and Ablaze co-director Alec Morgan. As Tiriki sees it, the question of whether or not Bill is the first Aboriginal filmmaker in Australia is moot. ‘We put a lot of energy and effort into the ideas of “first” and “biggest”,’ he chuckles. ‘But [Alec and I] look at Bill’s work in the context of the community that he sits in, and we look at those who picked up the mantle from him.’

A man for all seasons

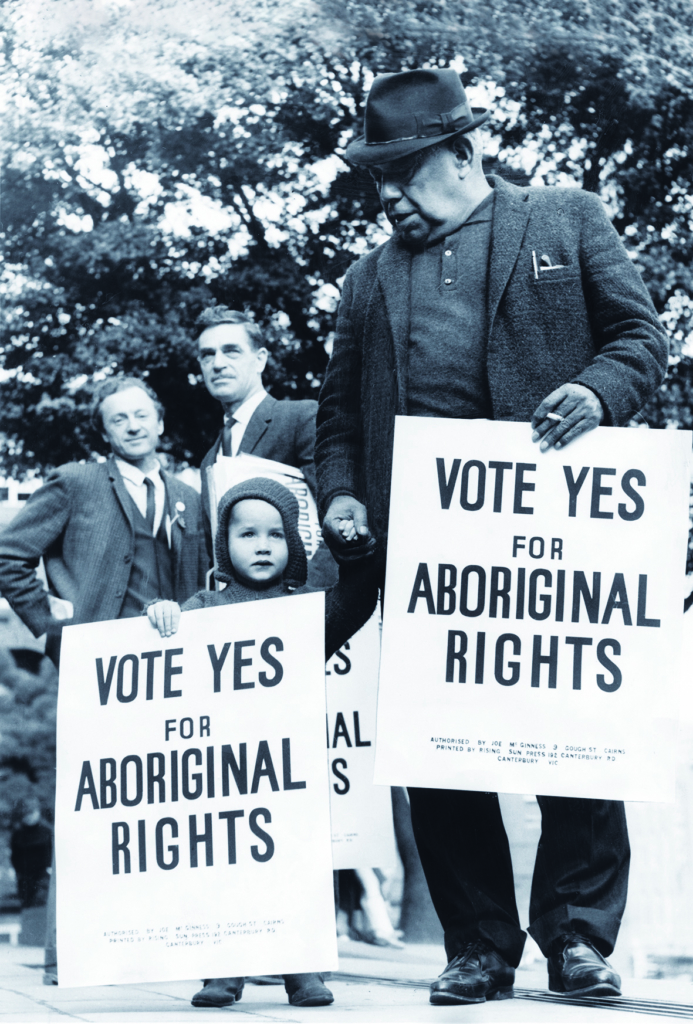

A witty and urbane man with a gift for public oration, Bill was a towering figure in Melbourne – and not just because he was notably tall. Born in 1906 at Cummeragunja Station, near the border between New South Wales and Victoria, he would go on to become a passionate proponent of racial equality who understood the power of cinema to communicate clearly to non-Indigenous people. Bill’s astounding accomplishments are too numerous to list in full, even in Ablaze, but they include rejuvenating the Aborigines (now Aboriginal) Advancement League, where he championed the cause of First Nations people specifically; throwing his weight behind the union movement together with his second wife, Scotswoman and Communist Party of Australia member Mary McLintock Kelly; and working as a magnetic figure in the arts scene, founding theatre companies that would tell First Nations stories.[3]See Ian Howey-Willis, ‘Onus, William Townsend (Bill) (1906–1968)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, 2000, <https://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/onus-william-townsend-bill-11308>, accessed 9 August 2021.

In all of these endeavours and more, Bill was surrounded by equally impassioned people – among them, Douglas Nicholls, Margaret Tucker and Geraldine Briggs – who pursued similar goals in their own way.[4]For a brief introduction to the work of these figures and fellow contemporaries, see ‘Worawa History Walk: Honouring “Change Makers” in Aboriginal Community Development’, Worawa Aboriginal College, <https://www.melbourne.vic.gov.au/SiteCollectionDocuments/Worawa-history-walk.pdf>, accessed 9 August 2021. This notion of collective achievement is key to the mission of Ablaze; as Tiriki notes, prior to the documentary positing his grandfather as the first Aboriginal filmmaker, it was often said[5]See, for example, Francesca Rizzoli, ‘Is Aboriginal Cinema a Niche? Not really’, SBS Italian, updated 15 June 2017, <https://www.sbs.com.au/language/english/is-aboriginal-cinema-a-niche-not-really>, accessed 9 August 2021. that Bruce McGuinness, director of Black Fire (1972) and A Time to Dream (1974), held that distinction:

I kind of see those two sitting together as one. It’s not so much about the individual here, but rather about the collective and what we’ve done together. If anything has been brought home to me, even more so during the course of making this film, it’s the sense of that community in which Bill was working […] I’m excited to think that maybe, one day, we’ll find someone who was making films before Bill.

Tiriki, a talented opera singer and head of the Wilin Centre for Indigenous Arts and Cultural Development at the University of Melbourne, was deeply moved by the resurfaced clip Morgan drew his attention to. Bill’s forays in filmmaking had been thought lost to the world in a caravan blaze. But here he was, brought to life on camera once more, caught on camera interacting with traditional dancers daubed with ochre. Other sequences in the black-and-white silent[6]A voiceover was recorded for the film by Bill but was lost. See Paul Dalgarno, ‘Ablaze: Tiriki Onus Resurfaces Vital Indigenous History Through a Film About His Grandfather’, University of Melbourne Faculty of Fine Arts and Music website, 6 August 2021, <https://finearts-music.unimelb.edu.au/about-us/news/tiriki-onus-ablaze-film-interview>, accessed 10 August 2021. film show Bill’s brother, Eric, walking the streets of Fitzroy with wife Wynne and an expressive theatrical work centred on the 1946 Pilbara strike – the longest in Australian history, and regarded as the first to have been explicitly organised to resist oppression of First Nations workers.[7]For more on the strike, see The Pilbara Aboriginal Strike, <https://www.pilbarastrike.org/>, accessed 8 August 2021. This strike is an integral part of the history that is connected to the great shame of Australian slavery, something that Morrison so recently, and erroneously, denied had ever occurred.[8]Morrison subsequently retracted and apologised for this claim. See Katharine Murphy, ‘Scott Morrison Sorry for “No Slavery in Australia” Claim and Acknowledges “Hideous Practices”‘, The Guardian, 12 June 2020, <https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2020/jun/12/scott-morrison-sorry-for-no-slavery-in-australia-claim-and-acknowledges-hideous-practices>, accessed 9 August 2021.

‘What really shines through, when you look at the type of stuff Bill was saying in the 1940s, is that it’s disturbingly as relevant now as it was back then,’ Tiriki observes. He acknowledges that, through his university role, his own advocacy in the arts and beyond comes from a place of great privilege that was not afforded his grandfather, whose movements around the country were constantly restricted. Bill and his political voice were seen as so threatening to the state that he was spied on by the newly emergent Australian Security Intelligence Organization (ASIO). As chilling as that is, history sometimes has a funny way of working against malicious intent, Tiriki reflects:

I find myself saying, ‘Thank god for ASIO,’ which is the most ironic and strange thing. Were it not for their rampant paranoia and the level of fear that drove them to surveil people like my grandfather, we wouldn’t have the records that we do now to go back and draw on […] Ironically, it has lent credence to the oral histories which have persisted in my family, and many others, for so long. Now we’re able to substantiate them, because the very people who were trying to suppress them have actually provided us with the means of proving our claims. It gives me great joy and keeps me warm at night.

The power of film persists, and newsreels played before films held great sway back then too, Tiriki says: ‘There was no television at this time; there was radio and print media, and that was about it. Film was cutting-edge.’ And the survival of even a fragment like this holds to account those who tried to suppress it, he points out. ‘We still have the opportunity now to be informed by what was going on back then.’

Seeing the future in our past

Given that Ablaze allows us the gift of understanding a fraction of the incredible achievements Bill was able to secure in the face of government hostility, the fact that this important document went unnoticed for so long is indicative of a persistent kind of cultural violence enacted by the current federal government: namely, the financial throttling of the NFSA and the National Archives of Australia.[9]See Elias Visontay, ‘“Inconceivable”: Why Has Australia’s History Been Left to Rot?’, The Guardian, 23 May 2021, <https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2021/may/23/inconceivable-why-has-australias-history-been-left-to-rot>; and Lisa Martin, ‘Australian Cultural Institutions Struggle to Survive as War Memorial Gets Half-billion Dollar Upgrade’, The Guardian, 3 November 2018, <https://www.theguardian.com/culture/2018/nov/03/years-of-savage-cuts-leave-australian-cultural-institutions-struggling-to-survive>, both accessed 9 August 2021. It’s an issue that engulfs Morgan – who explored the Stolen Generations and the Cummeragunja strike through the testimony of activists including Tucker, Briggs and Bill Reid in Lousy Little Sixpence (Gerald Bostock & Morgan, 1983) – with an energising fire, much to the amusement and admiration of good friend Tiriki.

‘This government has affected my life dramatically as a historian,’ Morgan says of the refusal to properly fund our national archival institutions, to the point where they are forced to go cap in hand to members of the public to secure the survival of invaluable records of our country’s story.[10]See Katina Curtis & Shane Wright, ‘Archive Passes the Hat in Desperate Bid to Save Australia’s History’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 16 May 2021, <https://www.smh.com.au/politics/federal/archive-passes-the-hat-in-desperate-bid-to-save-australia-s-history-20210516-p57sb3.html>, accessed 10 August 2021. He points, too, to the similarly antagonistic government approach to university funding[11]See Naaman Zhou, ‘Australian Universities Brace for “Ugly” 2022 After Budget Cuts’, The Guardian, 13 May 2021, <https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2021/may/13/australian-universities-brace-for-ugly-2022-after-budget-cuts>, accessed 9 August 2021. and to savage cuts to the public broadcaster[12]See Zoe Samios, ‘“Hunger Games”: Bungled Budget Cuts, Staff Exodus Take Toll on ABC’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 7 February 2021, <https://www.smh.com.au/business/companies/hunger-games-bungled-budget-cuts-staff-exodus-take-toll-on-abc-20210126-p56wur.html>, accessed 9 August 2021. as part of a bigger picture of preserving only the stories that serve narrow ends. ‘The National Film and Sound Archive used to have a public persona,’ he says. ‘That’s all closed down. They have to decide between preservation and getting it out to the public.’

Morgan relocated to Australia from New Zealand in the 1970s, and was frustrated by what he observed as an apathy, if not outright resistance, regarding the true history of the country. His work, both in terms of history and filmmaking, has thus been oriented towards bridging gaps in the colonial record, with a particular focus on Indigenous history. One aspect of these efforts has been helping to repatriate rediscovered footage back to elders, and Morgan was thus overjoyed when he was alerted to the clip that would inspire Ablaze: ‘I immediately recognised Eric Onus, and Bill kept popping up, and I thought, “This looks like a very interesting film.”’ He subsequently contacted Tiriki – who had created the opera William and Mary[13]See Carolyn Webb, ‘Opera, William and Mary, by Tiriki Onus’, The Age, 4 February 2014, <https://www.theage.com.au/entertainment/opera-william-and-mary-by-tiriki-onus-20140203-31xfp.html>, accessed 8 August 2021. about his grandparents, and who in turn was familiar with Morgan’s work on Lousy Little Sixpence – and a seven-year mission to bring the documentary to life was sparked. ‘We were very much aligned,’ Morgan recounts.

They were deep into the project when Morrison made his ahistorical claim about slavery’s non-existence in Australia. ‘We didn’t want to rush over or assume that people knew that there was segregation in Australia,’ Morgan says of the inclusion of distressing pictures of First Nations people in chains in the documentary. ‘Bill was trying to do something about it.’ Morgan felt great optimism during the 1980s that the tide of history was changing, but he believes that a lot of this reassuring work was throttled when long-serving prime minister John Howard came to power in 1996:

He started the history wars that really damaged the progress that was being made for Australia to change its understanding of its past. It just slammed back down to the old Captain Cook celebration.

Morgan recounts having experienced a great deal of pushback over the years, particularly from television producers who resisted this kind of open and honest reassessment of the nation’s dark past. He and Tiriki had to work hard to secure funding for Ablaze, with the Melbourne International Film Festival and Film Victoria integral to championing its cause. ‘There are a lot of great stories that have never been told,’ he says. ‘Bill was a true Australian hero, as were Geraldine and Margaret and many who spent their whole lives just trying to get equality.’

With the intergenerational trauma that continues to be wrought by the policies of attempted genocide and then of assimilation and the Stolen Generations, alongside over-policing, Aboriginal deaths in custody and children as young as ten being imprisoned,[14]See Michael Fowler & Sumeyya Ilanbey, ‘“Detention Damages These Children”: New Push to Raise Age of Criminality Above 10’, The Age, 18 May 2021, <https://www.theage.com.au/politics/victoria/detention-damages-these-children-new-push-to-raise-age-of-criminality-above-10-20210518-p57svf.html>, accessed 10 August 2021. attempting to come to grips with the enormity of Indigenous disadvantage and dispossession can be overwhelming. Morgan hopes Ablaze can play some small part in fighting back. ‘These situations should not be happening in Australia,’ he says. ‘It’s an absolute disgrace.’ Travelling to Port Hedland Wharf in the Pilbara while filming particularly underlined how far we still have to go, he recounts:

You look out and there are trains 2 kilometres long full of iron ore, coming in from all directions twenty-four hours a day, and there are twenty ships out there in the harbour. And over the horizon, there’s another twenty ships. And at the same time when we were there, the government was closing down 120 Aboriginal communities[15]See Helen Davidson, ‘WA Plan to Close 100 Remote and Indigenous Communities “Devastating”’, The Guardian, 18 November 2014, <https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2014/nov/18/wa-plan-to-close-100-remote-and-indigenous-communities-devastating>, accessed 10 August 2021. […] That’s the horrible situation of Australia today – that it’s got so much wealth and yet cries poor whenever any new ideas might come up about changing things.

Moving forward together

The mutual respect between the filmmakers is clear. For Tiriki’s part, he sees close collaboration between those of First Nations and non-Indigenous backgrounds as being vital to improving the nation. ‘You have to be able to bring people along on these journeys,’ he suggests, noting how integral the creation of safe spaces for ‘intercultural collaboration where non-Indigenous allies can contribute to the amplification of First Nations persons’ is to that process. Storytelling has been vital to this place for some 65,000 years or more, and the arts – including music, theatre and film – contribute to continuing that tradition. ‘The arts are always going to be the most powerful method for communicating our humanity, at the end of the day – which is what it boils down to,’ Tiriki says. He’s proud to work alongside Morgan towards that goal.

Knowing the history that Alec had as a collaborator with other First Nations storytellers and filmmakers, I felt that I was slipping into a space that we could make safe together. And we’ve had a lot of fun. [The documentary] has taken us nearly seven years to make, and we haven’t killed each other in that time. So I think we’re doing something right.

Endnotes

| 1 | See Andy Bull, ‘Surreal Spectacle of a Superbly Set Up Olympics with No One Here to Enjoy It’, The Observer, 24 July 2021, <https://www.theguardian.com/sport/2021/jul/24/surreal-spectacle-of-a-superbly-set-up-olympics-with-no-one-here-to-enjoy-it>, accessed 9 August 2021. |

|---|---|

| 2 | See Josh Taylor, ‘From “It’s Not a Race” to “Go for Gold”: How Scott Morrison Pivoted on Australia’s Covid Vaccine Rollout’, The Guardian, 29 July 2021, <https://www.theguardian.com/society/2021/jul/29/from-its-not-a-race-to-go-for-gold-how-scott-morrison-pivoted-on-australias-covid-vaccine-rollout>, accessed 9 August 2021. |

| 3 | See Ian Howey-Willis, ‘Onus, William Townsend (Bill) (1906–1968)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, 2000, <https://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/onus-william-townsend-bill-11308>, accessed 9 August 2021. |

| 4 | For a brief introduction to the work of these figures and fellow contemporaries, see ‘Worawa History Walk: Honouring “Change Makers” in Aboriginal Community Development’, Worawa Aboriginal College, <https://www.melbourne.vic.gov.au/SiteCollectionDocuments/Worawa-history-walk.pdf>, accessed 9 August 2021. |

| 5 | See, for example, Francesca Rizzoli, ‘Is Aboriginal Cinema a Niche? Not really’, SBS Italian, updated 15 June 2017, <https://www.sbs.com.au/language/english/is-aboriginal-cinema-a-niche-not-really>, accessed 9 August 2021. |

| 6 | A voiceover was recorded for the film by Bill but was lost. See Paul Dalgarno, ‘Ablaze: Tiriki Onus Resurfaces Vital Indigenous History Through a Film About His Grandfather’, University of Melbourne Faculty of Fine Arts and Music website, 6 August 2021, <https://finearts-music.unimelb.edu.au/about-us/news/tiriki-onus-ablaze-film-interview>, accessed 10 August 2021. |

| 7 | For more on the strike, see The Pilbara Aboriginal Strike, <https://www.pilbarastrike.org/>, accessed 8 August 2021. |

| 8 | Morrison subsequently retracted and apologised for this claim. See Katharine Murphy, ‘Scott Morrison Sorry for “No Slavery in Australia” Claim and Acknowledges “Hideous Practices”‘, The Guardian, 12 June 2020, <https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2020/jun/12/scott-morrison-sorry-for-no-slavery-in-australia-claim-and-acknowledges-hideous-practices>, accessed 9 August 2021. |

| 9 | See Elias Visontay, ‘“Inconceivable”: Why Has Australia’s History Been Left to Rot?’, The Guardian, 23 May 2021, <https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2021/may/23/inconceivable-why-has-australias-history-been-left-to-rot>; and Lisa Martin, ‘Australian Cultural Institutions Struggle to Survive as War Memorial Gets Half-billion Dollar Upgrade’, The Guardian, 3 November 2018, <https://www.theguardian.com/culture/2018/nov/03/years-of-savage-cuts-leave-australian-cultural-institutions-struggling-to-survive>, both accessed 9 August 2021. |

| 10 | See Katina Curtis & Shane Wright, ‘Archive Passes the Hat in Desperate Bid to Save Australia’s History’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 16 May 2021, <https://www.smh.com.au/politics/federal/archive-passes-the-hat-in-desperate-bid-to-save-australia-s-history-20210516-p57sb3.html>, accessed 10 August 2021. |

| 11 | See Naaman Zhou, ‘Australian Universities Brace for “Ugly” 2022 After Budget Cuts’, The Guardian, 13 May 2021, <https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2021/may/13/australian-universities-brace-for-ugly-2022-after-budget-cuts>, accessed 9 August 2021. |

| 12 | See Zoe Samios, ‘“Hunger Games”: Bungled Budget Cuts, Staff Exodus Take Toll on ABC’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 7 February 2021, <https://www.smh.com.au/business/companies/hunger-games-bungled-budget-cuts-staff-exodus-take-toll-on-abc-20210126-p56wur.html>, accessed 9 August 2021. |

| 13 | See Carolyn Webb, ‘Opera, William and Mary, by Tiriki Onus’, The Age, 4 February 2014, <https://www.theage.com.au/entertainment/opera-william-and-mary-by-tiriki-onus-20140203-31xfp.html>, accessed 8 August 2021. |

| 14 | See Michael Fowler & Sumeyya Ilanbey, ‘“Detention Damages These Children”: New Push to Raise Age of Criminality Above 10’, The Age, 18 May 2021, <https://www.theage.com.au/politics/victoria/detention-damages-these-children-new-push-to-raise-age-of-criminality-above-10-20210518-p57svf.html>, accessed 10 August 2021. |

| 15 | See Helen Davidson, ‘WA Plan to Close 100 Remote and Indigenous Communities “Devastating”’, The Guardian, 18 November 2014, <https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2014/nov/18/wa-plan-to-close-100-remote-and-indigenous-communities-devastating>, accessed 10 August 2021. |