A destabilising lack of history makes even the most basic of recognitions impossible, and the underlying struggle for domination over an unacknowledged Other in the landscape produces an imaginative landscape charged with guilt and uncertainty.

– Kathleen Steele[1]Kathleen Steele, ‘Fear and Loathing in the Australian Bush: Gothic Landscapes in Bush Studies and Picnic at Hanging Rock’, Colloquy: Text, Theory, Critique, no. 20, 2010, p. 41, available at <https://www.monash.edu/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/1763896/steele.pdf>, accessed 5 November 2021.

You can often hear magpies warbling in New Gold Mountain. The earthy palette, too – browns, reds and oranges emulating Ballarat’s dust and heat – infuses this indulgent SBS western with a distinctively Australian feel.

The four-part miniseries tells the tale of the Victorian gold rush through the eyes of Chinese migrants, a sizeable demographic within the 1850s mining community. Earlier attempts to recount this well-traversed chapter of local history, such as the UK production Eureka Stockade (Harry Watt, 1949), have flopped.[2]See ‘Key Details’, ‘Eureka Stockade’, Ozmovies, <https://www.ozmovies.com.au/movie/eureka-stockade>, accessed 11 March 2022. Although New Gold Mountain has both more and less political flavour than Watt’s tale of worker uprising against colonial authority, its fresh perspective – along with its grand visuals and high-calibre acting – has been greeted with a considerably more enthusiastic critical reception.[3]See, for example, Eric Jiang, ‘TV Review: New Gold Mountain Is a Captivating Achievement’, ScreenHub, 14 October 2021, <https://www.screenhub.com.au/news/reviews/tv-review-new-gold-mountain-is-a-captivating-achievement-1475813/>; and Luke Buckmaster, ‘New Gold Mountain Review – Lush Neo-western Takes a New Route Through Gold Rush Australia’, The Guardian, 13 October 2021, <https://www.theguardian.com/tv-and-radio/2021/oct/13/new-gold-mountain-review-lush-neo-western-takes-a-new-route-through-gold-rush-australia>, both accessed 11 March 2022.

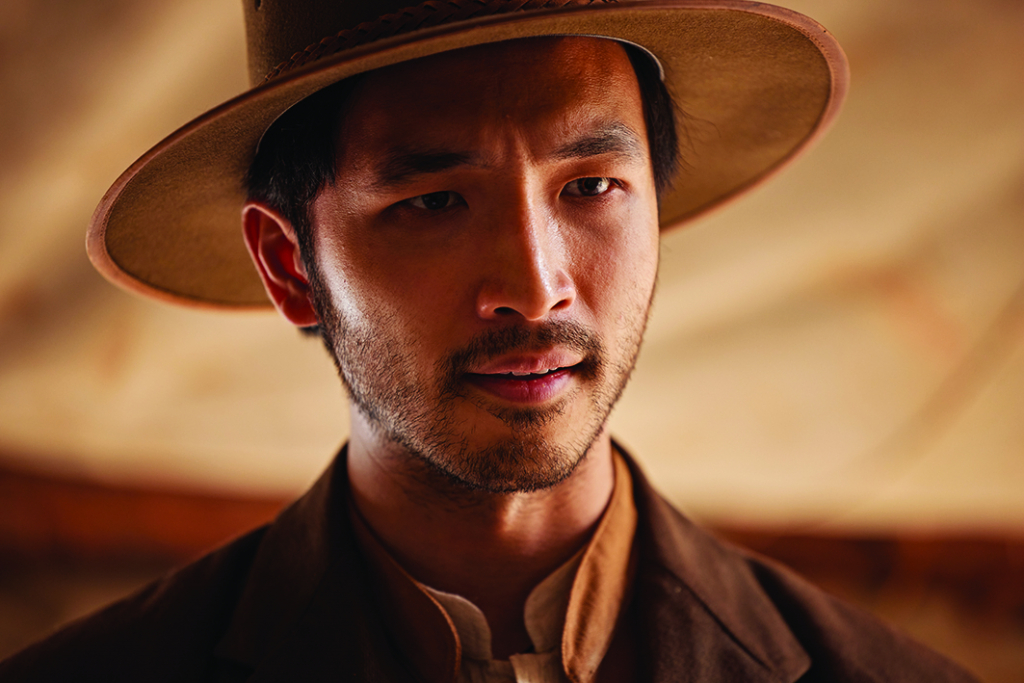

To tell this story, New Gold Mountain borrows a well-worn formula from a colonial neighbour: the western. Camp headman Leung Wei Shing (Yoson An) fills the boots of the rootless cowboy archetype, while Ballarat’s Golden Point mining camp – crowded with bodies dusty from digging holes in the ground – stands in for the precarious, cactus-spotted frontier of the Wild West. Shing exploits the goldfields for wealth and posterity, both for his own sake and that of the Brotherhood – a secret society of Chinese migrants led by Zhang Lei (Mabel Li), acting as a proxy for her powerful father.

For the most part, however, gold fades into the background. Midway through the first episode, Shing finds a white woman, Annie Thomas (Maria Angelico), dead in the bush near his camp. Returning to her corpse, he is disorientated by an invisible force: he quivers under foreboding gum trees; a kangaroo holds him in its spooky gaze. From this point on, the mystery of her death – and where the blame for it lies – infiltrates the social networks of the Ballarat township and its nearby mining camps.

Yet Annie’s death inconsistently influences the plot. For Shing, her death poses a threat to the Chinese mining community, who already live in constant fear of being targeted by authorities and now risk being scapegoated for the murder. This premise is somewhat undermined by the fact that, as the series plays out, the police and Annie’s Irish husband, Patrick (Christopher James Baker), hardly seem to care that she died at all – let alone who the culprit was. Even as Shing and newspaper proprietor Belle (Alyssa Sutherland) conduct their own investigations, frequent cameos of quirky locals – including fetus-collecting doctors, awkward teen outlaws and badly dancing European women – further dilute the weight of Annie’s death. These overcrowded, incongruent and somewhat plot-hole-riddled elements, which detract from New Gold Mountain’s promising central narrative, suggest that the series’ ambitions may have hijacked a more cohesive, informed production.

The Australian frontier

The most prominent example of this dissonance lies in the contrasts between director Corrie Chen’s stated intentions – to ‘redefine our perception of frontier Australia’, ‘put Chinese-Australian cowboys on screen’ and ‘revise the canon of the classic western’[4]Corrie Chen, quoted in ‘Who and What to Look Out for in New Gold Mountain’, The Guardian, 13 October 2021, <https://www.theguardian.com/sbs-on-demand-new-gold-mountain/2021/oct/13/who-and-what-to-look-out-for-in-new-gold-mountain>, accessed 15 March 2022. – and how the series actually deals with these complex histories.

In New Gold Mountain, as in so many American westerns, the frontier simultaneously exists as a perilous landscape and a tempting barrier for the robust-yet-resourceful cowboy to crack open and meet the bountiful unknown. Indeed, Wild West scenarios can easily translate to mid-eighteenth-century settler-colonial Australia’s ambitions of dominating and conquering the land beyond its major coastal outposts. But there are notable divergences, too – where a traditional western might feature showy gun-wielding or absurd bar fights, New Gold Mountain dedicates most of its screen time to broody dialogue, with its four episodes dominated by hot-and-heavy conversations.

Over the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the western emerged in different artforms, from roadshows to literature, before becoming a fan-favourite film genre in the US.[5]See ‘Western’, Encyclopaedia Britannica, <https://www.britannica.com/art/western>, accessed 15 March 2022. East Coast creatives crafted a vision of the Wild West that bore little resemblance to the reality of the country’s westward expansion, a history less wild than it was full of hard labour and daily struggles to survive.[6]See David Lamb, ‘Bones Don’t Lie: Wild West Life: Sweet It Wasn’t’, Los Angeles Times, 27 April 1988, <https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1988-04-27-mn-1647-story.html>, accessed 15 March 2022. Through this disparity between truth and fiction, what the western reveals most of all is the capacity of a culture to warp its national vision of itself.

A historical revision told once is fiction, a story; told many times, it becomes a myth, an agenda. Richard Slotkin, a cultural critic versed in the Wild West, defines myth as

the primary language of historical memory: a body of traditional stories that have, over time, been used to summarize the course of our collective history and to assign ideological meanings to that history.[7]Richard Slotkin, ‘Myth and the Production of History’, in Sacvan Bercovitch & Myra Jehlen (eds), Ideology and Classic American Literature, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1986, p. 70.

Over the decades since the western hit its peak of popularity and began a long-perceived ‘downward slope of its evolutionary cycle’,[8]Melenia Arouh, ‘Matthew Carter, Myth of the Western: New Perspectives on Hollywood’s Frontier Narrative Neil Campbell, Post-Westerns: Cinema, Region, West’, European Journal of American Studies, 22 June 2015, <https://journals.openedition.org/ejas/10850>, accessed 15 March 2022. filmmakers have revised and challenged the genre. It might seem that there are only so many times that the wheel can be reinvented; but the shoe, for Chen and series creator/co-writer Peter Cox, still fits.

Notably, however, New Gold Mountain’s local frontier also sits beyond the western canon, reflecting the tension between settlers and land that has often infused Australian art. In a study of early Australian literature, Steele expresses that the bush represents a ‘threatening Other’ that offers ‘no solace’ for settlers to struggle against.[9]Steele, op. cit., p. 43. In reality, the land has culture and home: the Wathawurung people have continuously occupied the land on which the Victorian goldfields have stood for many thousands of years. In colonial myth, however, the settler-cum-cowboy must overcome the empty land’s threat. As Tracy Ireland argues, ‘This concept of an environment somehow opposed to the fostering of cultural development is central to colonial narratives of settler history in Australia.’[10]Tracy Ireland, ‘“The Absence of Ghosts”: Landscape and Identity in the Archaeology of Australia’s Settler Culture’, Historical Archaeology, vol. 37, no. 1, 2003, p. 56.

In an interview with Junkee, Chen has remarked that she fears the bush[11]Merryana Salem, ‘SBS’s New Gold Mountain Examines What It Means to Belong in Australia’, Junkee, 21 October 2021, <https://junkee.com/corrie-chen-new-gold-mountain/311820>, accessed 23 October 2021. – an admission that may provide some indication as to why New Gold Mountain reinforces this popular conception of the Australian ‘frontier’. For the series’ characters, the bush is hostile; the uncontrolled landscape kills the white woman and threatens Shing’s frontier ambitions. In comparison to the classic western’s sprawling landscape photography, New Gold Mountain prefers to stay within the huddled townscape. Scenes often occur in the low-lit interiors of tents shadowing characters from the burning sun, or comprise sedentary frames of street-side conversations energised by the bustling community in the background. The filming of the bush – the wild frontier, the ‘Other’ – never has this sense of enthusiasm or intimacy; the rare scenes shot there use a shallow lens range and lack depth of colour.

Such focus on built-up environments draws attention away from the frontier and towards the ‘civilisation’ on its edges. Compared to the shabby towns of most Wild West–set films, New Gold Mountain’s shooting location in the open-air museum of Sovereign Hill feels positively swanky. The detailed inclusion of well-researched props – from newspapers to items on shop shelves – playfully offsets this established backdrop. But the series goes beyond merely playing pretend in the Sovereign Hill of childhood school excursions past. At the end of Episode 1, the Chinese camp holds a Spring Festival; striking visuals of red and purple fireworks and lanterns floating over the night-time horizon offer new aesthetic imaginings of early Victorian culture, wildly differing from long-told British-centred narratives.

New Gold Mountain highlights the diverse communities that populated these early colonial settlements. The gold rush brought tens of thousands of Chinese arrivals to Victoria,[12]See ‘Many Roads: Stories of the Chinese on the Goldfields’, Victorian Collections, <https://victoriancollections.net.au/stories/many-roads-stories-of-the-chinese-on-the-goldfields>, accessed 16 March 2022. but they weren’t alone; the many ways characters in the series pronounce ‘Melbourne’ nods to the motley crew populating this makeshift society. The series also suggests that this environment allowed women to carve out a place: townsfolk regularly resource Indigenous Hattie’s (Leonie Whyman) knowledge in medicine, hunting and tracking; Belle intimidates her journalistic subjects; and, through Li’s transfixing performance, Lei holds power as a seductive, cunning antagonist. But while these representations celebrate the frontier’s multicultural character, the series lacks any juxtaposing critique around this budding community colonising the land for financial gain.

Whose stories?

In foregrounding Chinese-Australian characters, New Gold Mountain finds itself part of the overdue movement to make Australian TV feel like watching TV about Australia. Revisualising the country’s past in the way the series does weakens the white stranglehold on national identity.[13]For more on this, see Naaman Zhou, ‘Whitewashed: Why Does Australian TV Have Such a Problem with Race?’, The Guardian, 18 April 2021, <https://www.theguardian.com/tv-and-radio/2021/apr/18/whitewashed-why-does-australian-tv-have-such-a-problem-with-race>, accessed 16 March 2022. But generally speaking, the screen industry poorly models this concept. Australian television represents characters of non-Anglo-Celtic backgrounds at just over half the rate that they exist in the population.[14]Screen Australia, Seeing Ourselves: Reflections on Diversity in Australian TV Drama, 2016, p. 3, <https://www.screenaustralia.gov.au/getmedia/157b05b4-255a-47b4-bd8b-9f715555fb44/tv-drama-diversity.pdf>, accessed 23 October 2021. A lack of both diverse local roles and ‘colour-blind’ casting has forced many Asian-Australian actors to find success overseas.[15]ibid., p. 34.

In the recent Australian series Bump and The Unusual Suspects – both set in modern-day Sydney – casts that prominently feature (respectively) Latino and Filipino performers reflect their communities and local talent alike. In these shows, a culturally diverse identity isn’t depicted as a bold statement, but a casual default – as it should be. But, as always in this country, more work needs to be done.

By centring Chinese-Australian cowboys, New Gold Mountain resists almost two centuries of cultural erasure – the past fights the present. In newspaper The Ballarat Star, Shing eyes off a headline about a ‘Chinese’ virus. Upper-class British characters’ rhetoric about Chinese people being ‘locusts’ spoiling their colonial claim echoes One Nation founder Pauline Hanson’s 1996 maiden parliamentary speech warning that Australia was on the verge of being ‘swamped by Asians’.[16]Pauline Hanson, quoted in ‘Pauline Hanson’s 1996 Maiden Speech to Parliament: Full Transcript’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 15 September 2016, <https://www.smh.com.au/politics/federal/pauline-hansons-1996-maiden-speech-to-parliament-full-transcript-20160915-grgjv3.html>, accessed 16 March 2022. Yet the series only samples racism in passing – snide comments, a random drunken attack and discriminatory taxation – rather than offering a nuanced reflection of the extent of systemic discrimination and violence in Australia (either then or now).

In a think piece criticising the emphasis on pop-culture representation in the #StopAsianHate movement, Filipina-Australian writer Patricia Arcilla argues that screen creators should be willing to probe into ‘dark, ugly territories, the systems and stories that shaped the hate we see today’.[17]Patricia Arcilla, ‘Now You See Us: On the Shortcomings of #StopAsianHate’, Sydney Opera House website, 19 October 2021, <https://www.sydneyoperahouse.com/digital/articles/talks-ideas/now-you-see-us-stop-asian-hate.html>, accessed 23 October 2021. In this regard, New Gold Mountain’s references to historical racial power dynamics fall short. The Buckland riot – a large-scale attack against Chinese miners in 1854[18]See Tony Wright, ‘A Thorny Trail from Buckland to Our Battles with Beijing’, The Age, 5 December 2020, <https://www.theage.com.au/national/victoria/a-thorny-trail-from-buckland-to-our-battles-with-beijing-20201203-p56k8y.html>, accessed 17 March 2022. – only receives a blink-and-you’ll-miss-it reference, while Indigenous tracker Tom (Zach Blampied) is presented solely as a victim of police brutality. The heroes of the traditional western sought to conquer the ‘Indian’; in this 2021 revision of the genre, one of the only two First Nations characters in the series is given little characterisation or agency. Despite Chen and Cox’s mission to ‘shin[e] a light on forgotten events’,[19]See Gold website, <https://www.sbs.com.au/gold/new-gold-mountain/>, accessed 17 March 2022. New Gold Mountain only superficially brushes the sores of colonial violence. A better reflection of Australia’s diverse make-up is needed on our screens, but a production situated within an especially fraught history should be setting the bar higher than mere representation. As Arcilla puts it, ‘We can no longer settle for simply being seen.’[20]Arcilla, op. cit.

Every myth desires to reveal a truth. In the US, the traditional western reached into the nation’s past and produced a fantasy that lifted some up and pushed others down. New Gold Mountain’s historical drama does better by using the genre to represent a historically marginalised Australian community; but, without confronting influences that continue to injure open wounds, the series ultimately adds yet another palatable national vision to the western canon. The Australian frontier needs storytellers cognisant of its complexity – in terms of historical reality and imagination – in order for its story, with or without cowboys, to be properly told.

Endnotes

| 1 | Kathleen Steele, ‘Fear and Loathing in the Australian Bush: Gothic Landscapes in Bush Studies and Picnic at Hanging Rock’, Colloquy: Text, Theory, Critique, no. 20, 2010, p. 41, available at <https://www.monash.edu/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/1763896/steele.pdf>, accessed 5 November 2021. |

|---|---|

| 2 | See ‘Key Details’, ‘Eureka Stockade’, Ozmovies, <https://www.ozmovies.com.au/movie/eureka-stockade>, accessed 11 March 2022. |

| 3 | See, for example, Eric Jiang, ‘TV Review: New Gold Mountain Is a Captivating Achievement’, ScreenHub, 14 October 2021, <https://www.screenhub.com.au/news/reviews/tv-review-new-gold-mountain-is-a-captivating-achievement-1475813/>; and Luke Buckmaster, ‘New Gold Mountain Review – Lush Neo-western Takes a New Route Through Gold Rush Australia’, The Guardian, 13 October 2021, <https://www.theguardian.com/tv-and-radio/2021/oct/13/new-gold-mountain-review-lush-neo-western-takes-a-new-route-through-gold-rush-australia>, both accessed 11 March 2022. |

| 4 | Corrie Chen, quoted in ‘Who and What to Look Out for in New Gold Mountain’, The Guardian, 13 October 2021, <https://www.theguardian.com/sbs-on-demand-new-gold-mountain/2021/oct/13/who-and-what-to-look-out-for-in-new-gold-mountain>, accessed 15 March 2022. |

| 5 | See ‘Western’, Encyclopaedia Britannica, <https://www.britannica.com/art/western>, accessed 15 March 2022. |

| 6 | See David Lamb, ‘Bones Don’t Lie: Wild West Life: Sweet It Wasn’t’, Los Angeles Times, 27 April 1988, <https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1988-04-27-mn-1647-story.html>, accessed 15 March 2022. |

| 7 | Richard Slotkin, ‘Myth and the Production of History’, in Sacvan Bercovitch & Myra Jehlen (eds), Ideology and Classic American Literature, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1986, p. 70. |

| 8 | Melenia Arouh, ‘Matthew Carter, Myth of the Western: New Perspectives on Hollywood’s Frontier Narrative Neil Campbell, Post-Westerns: Cinema, Region, West’, European Journal of American Studies, 22 June 2015, <https://journals.openedition.org/ejas/10850>, accessed 15 March 2022. |

| 9 | Steele, op. cit., p. 43. |

| 10 | Tracy Ireland, ‘“The Absence of Ghosts”: Landscape and Identity in the Archaeology of Australia’s Settler Culture’, Historical Archaeology, vol. 37, no. 1, 2003, p. 56. |

| 11 | Merryana Salem, ‘SBS’s New Gold Mountain Examines What It Means to Belong in Australia’, Junkee, 21 October 2021, <https://junkee.com/corrie-chen-new-gold-mountain/311820>, accessed 23 October 2021. |

| 12 | See ‘Many Roads: Stories of the Chinese on the Goldfields’, Victorian Collections, <https://victoriancollections.net.au/stories/many-roads-stories-of-the-chinese-on-the-goldfields>, accessed 16 March 2022. |

| 13 | For more on this, see Naaman Zhou, ‘Whitewashed: Why Does Australian TV Have Such a Problem with Race?’, The Guardian, 18 April 2021, <https://www.theguardian.com/tv-and-radio/2021/apr/18/whitewashed-why-does-australian-tv-have-such-a-problem-with-race>, accessed 16 March 2022. |

| 14 | Screen Australia, Seeing Ourselves: Reflections on Diversity in Australian TV Drama, 2016, p. 3, <https://www.screenaustralia.gov.au/getmedia/157b05b4-255a-47b4-bd8b-9f715555fb44/tv-drama-diversity.pdf>, accessed 23 October 2021. |

| 15 | ibid., p. 34. |

| 16 | Pauline Hanson, quoted in ‘Pauline Hanson’s 1996 Maiden Speech to Parliament: Full Transcript’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 15 September 2016, <https://www.smh.com.au/politics/federal/pauline-hansons-1996-maiden-speech-to-parliament-full-transcript-20160915-grgjv3.html>, accessed 16 March 2022. |

| 17 | Patricia Arcilla, ‘Now You See Us: On the Shortcomings of #StopAsianHate’, Sydney Opera House website, 19 October 2021, <https://www.sydneyoperahouse.com/digital/articles/talks-ideas/now-you-see-us-stop-asian-hate.html>, accessed 23 October 2021. |

| 18 | See Tony Wright, ‘A Thorny Trail from Buckland to Our Battles with Beijing’, The Age, 5 December 2020, <https://www.theage.com.au/national/victoria/a-thorny-trail-from-buckland-to-our-battles-with-beijing-20201203-p56k8y.html>, accessed 17 March 2022. |

| 19 | See Gold website, <https://www.sbs.com.au/gold/new-gold-mountain/>, accessed 17 March 2022. |

| 20 | Arcilla, op. cit. |