In the series of interviews John Pilger did in 1983 for Channel 4 in England – appropriately called The Outsiders – one episode concentrated on the Australian journalist Wilfred Burchett, a man whose professional career, surrounded as it was by controversy and acrimony, Pilger clearly held in great respect. Later he was to write of Burchett: ‘For this much loved and much hated man the roads of good and evil, right and wrong, were discernible – he never had any doubts about which one to take’. During his lifetime Burchett had broken his journalistic neutrality to work untiringly against the spread of nuclear weapons. He had been accused of being a spy, a communist, a traitor and for seventeen years he was a man without a country when the Australian government refused to replace his lost passport. There is a strong sense, in Pilger’s description, of the older journalist being an appropriate resume of his own ethical position.

John Pilger employs the television documentary in the way the Eighteenth and early Nineteenth Century radicals employed the printed broad sheet: to fire off a political broadside at some particularly offensive target fronting for hypocrisy, vested interests and injustice. There is more than a touch of William Blake and William Cobbett about his passion. This visible and verbal commitment isn’t at all fashionable in the present climate for a number of reasons.

The emerging conditions of the nasty Nineties – which followed the Selfish Seventies and the Hard Faced Eighties – at least in the developed democracies – has encouraged a de-politicisation in civil society which now assumes that it is unfashionable to hold opinions or ideas about any subject which extends beyond immediate self-gratification. To declare a social conscience is to be ‘uncool’, worse to practise coercion, to subvert the unspoken (but still authoritative) rules of the post modern. Ironically, the politically correct stances of those formerly on the Left have, in these post Cold War days been occupied by the thought police of the Right so that political correctness of whatever hue is treated with extreme suspicion. In such a climate the professional partiality of an investigative reporter like Pilger is definitely not au fait. He harangues and pierces our indifference to the suffering caused by humanity to humanity like some ageing but focused survivor from a more innocent, more politically angry era.

Admirable as this stance is in many ways, it is by no means as unequivocal as it appears nor free of political ambiguity, as we shall see.

I remember watching a debate on BBC television in the late Sixties in which the question of professional impartiality, particularly on the part of reporters, anchors in studio debates and documentary filmmakers was discussed with that leisurely sang froid which successfully masks the most bitter controversies of the British. In those years the question of South Africa and Rhodesia was a particularly hot topic because of the discrepancy between public condemnation of the inequalities of race in those countries and the massive size of British investment in their economies. So the Director General of the BBC had issued a directive to the effect that in order to represent consensus in the community, henceforth reporters must strike a neutral position of equivalence, particularly when dealing with politically controversial subjects. I remember a visibly discomforted Director General attempting to defend this policy against the protests of Jonathan Dimbleby who attacked the idea on the grounds that it was intellectually impossible to place an adjudicator in a position that wasn’t immersed in political bias: if controversy in BBC terms were to approximate a see-saw, with equal weight on either side, the question of the ground on which the fulcrum stood was one which involved a politically oriented choice.

With his first documentary for TV in 1970, The Quiet Mutiny, appropriately for our purposes a film dealing with the American conscripts sent to Vietnam, John Pilger fell foul of this policy. The American ambassador to the Court of St. James, Walter Annenberg, complained to the Director General of ITA, Sir Robert Fraser, about the film’s visible anti-American bias. Fraser, who in his report described Pilger’s work as ‘grossly unbalanced and in serious breach of the code of impartiality’, later admitted he hadn’t actually seen the film. But an even more farcical solution was struck. A detail of the impartiality clause allowed that as long as balance could be achieved elsewhere in a series, a single program could be transmitted as a ‘personal view’. Pilger gleefully records in his book Heroes that vainly searching for balance and unable to come up with an alternative view about Vietnam, the producers went to air with a feature about Ted Heath’s yacht which provided ballast if not balance.

Not only is the BBC’s attempt to find a neutral centre point as futile as Archimedes’ equation to dislodge the earth by a lever fulcrumed on a point in deep space: it also conveniently elides questions to do with the ethical position of the filmmaker, his or her passion, judgement and political commitment. If you make a film condemning the Holocaust, should you then in the name of impartiality invite a neo-Nazi into a studio to present the arguments, however perverse, in favour of genocide? Clearly, seen from this perspective no film, no documentary, can possibly occupy neutral ground and it is within this envelope of a personal adherence to a larger notion of justice that Pilger’s documentaries should be viewed.

A few years ago the columnist for the Right wing British publication The Spectator Peregrine Worsthorne invented a new, critically opprobrious word: ‘Pilgered’ – ‘I’ve been Pilgered’, Worsthorne declared of the journalist’s attentions to his writing on the subject of apartheid. The term was later picked up by our own Minister for Foreign Affairs, Gareth Evans, outraged at Pilger’s accusations of the Minister’s collusion in the suppression of civil liberties by the Indonesian authorities on the island of Timor. A servile Managing Director of the ABC promptly refused to show the film on ABC television and it was subsequently screened on one of the commercial networks. What does it mean to be Pilgered? For those in power it is to be exposed to a sharp light which shines into the gap between their public pronouncements and their policies. As one of Pilger’s role models, the great late I.F.Stone, once declared: ‘Every government is run by liars and nothing they say should be believed’.

But to Pilger’s detractors the term has a different connotation – one that would paint the reporter as visibly biased, deliberately distorting the visible evidence to a pre-conceived personal program, one that is clearly Left, anti-American, anti-capitalist, melting down all complexities, paradoxes and contradictions to blend into a highly spiced stew of moral outrage. And one must ask how accurate such a criticism is.

In his 1978 film Do You Remember Vietnam? the Pilger style (greatly assisted by his long time producer David Munro) is already evident. The documentary maker is the central figure in his own film. He has already broken the rule of the neutral observer, the hidden commentator. He has put himself on display. His source of outrage is the inhumanity of men. ‘Vietnam’, he declares in that voice whose tones invoke those of a Non-Conforming Minister, ‘was a laboratory for weapons’. We are shown footage of B52s excreting death. Devastated wastelands pocked with bomb craters. Unbearable photos of maimed children.

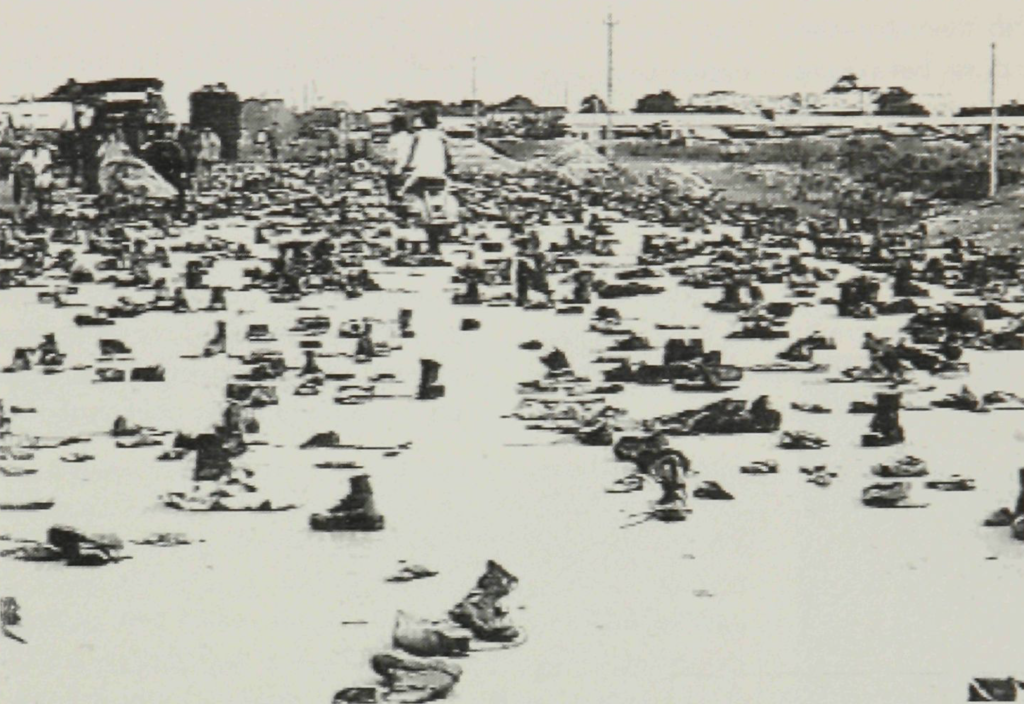

He takes us on a personal tour of downtown Saigon, Da Nang, Hue, Hanoi – scenes which he covered for the British media as the war progressed. ‘What is Vietnam like’? he asks. ‘What do the people think of us’? And I’m disturbed to find that, against my expectations of the news documentary, he makes no attempt to answer his own questions. His ploy is to engage our attention while he strides down a personal path of memory, angry fact – ‘More than one third of Americans polled couldn’t remember on which side the USA fought in Vietnam’ – and some kind of Manichean engagement with the evidence of injustice. He clearly sides with the Vietnamese, not in their victory but in their agony, ‘the longest war of the 20th Century’, and two years after the war ended it is somehow touching to observe his continuing anger at the perfidy of it all. He shows a black and white photograph of people shot and laid out like rabbits: ‘They were all Viet Cong – even the babies’. He is like a fierce and brilliant prosecutor before a war crimes tribunal. But who is the accused and what penalty can he possibly demand?

If this earlier film of Vietnam seems baffled in its anger, the new film Vietnam: the Last Battle has found its occasion and its target. If the first part of the film is a re-run of the 1977 footage and its accompanying outrage, the last two thirds gets down to a representation of the new threat to Vietnam: ironically its incorporation within the capitalist sphere of influence and investment after twenty years of trade embargo and economic boycott at sources of restitution like the World Bank by its former, defeated enemy, the USA. We are given interviews with a chief government economic adviser who sees the future of Vietnam as lying in cheap labour, exploitable resources and vast foreign investment, an ideological turn around gleefully supported by a cast of foreign businessmen as grotesque and mono-visioned as anything dreamed up by Brecht – Pilger is no amateur when it comes to drawing out their values. On the dissident side he talks to a gentle sociologist with self-confessed nationalist sympathies who offers a hope of decent social services and equality of opportunity for her fellow citizens.

But the true centre of protest is again Pilger himself. He employs a curiously revealing phrase in his opening declaration of the film’s intention: to rescue one of the epic national struggles of the 20th Century. It suggests that at heart Mr. Pilger is a romantic whose heart and mind focuses most sharply in the light of epic struggles already doomed to be swamped, as much by the mundanities of materialism as by carpet bombing. His vision of decency, human values, an equitable social system, universal justice is already doomed. And it is in the light of that bonfire of doomed hope that he preaches.

But who is his intended audience? Does he address the raggle-taggle survivors of the Sixties who cut our political eye teeth on the anti-war movement and still remember what it’s like to feel political passion? Does he play on us like a latter-day Liszt striking black and white keys labelled Vietnam, Cambodia, Burma, Timor, Palestine, South Africa? In which case he is telling us what we already know, what we want to know about the great moral arenas of contest between the forces of light and darkness. Moral outrage as self-gratification.

Or is his target the self-nullifying political indifference of the opposition, that more than one third of the American public (and how many in Australia?) who not only don’t know what their country perpetrated in Vietnam but whose side the U S Government actually fought on; those large numbers of Australians who can’t find Timor on a map; the supporters of Chirac who believe it’s okay to do their radio-active dumping on the helpless inhabitants of the South Pacific region because the tests are removed from Continental France? Surely the very style of the Pilger polemic – confrontation on a personal level – precludes any possibility that he might convince, convert or alert the indifferent or the antagonistic? And here I must confess I bump up against one of my more serious doubts about the Pilger documentary technique. Superb as he is as an angry prosecutor of injustice, he is challenged by the very ideological conformity he sets out to attack. The implication of his style asks us to trust him, to make the targets of his scorn and anger ours, with very little supporting documentary evidence presented to support his case. The fact that he has identified a locus of big power criminality is sufficient to condemn the perpetrators. He doesn’t proceed by strength of argument but by strength of feeling.

Yet a substantial component of his position is that we should not trust what we are told by people occupying positions of authority. Both the Vietnam films play with a technique of running official Presidential statements about the conduct of the Vietnam war – Reagan’s ‘Ours was in truth a noble cause’ for example, while showing violent and countervailing footage – a Vietcong suspect being deliberately drowned by ARVN forces in a paddy field. Don’t trust the emotional hype. Yet the Pilger polemic asks, demands concession while allowing no room for difference of interpretation or dissent from the presentation. If you disagree you are, at best, a collaborator in big power injustice.

The problem as I see it is not the intensity of moral outrage but the exclusive and ultimately monotonous nature of its presentation.

Pilger’s method is at its best when he lets loose his sense of irony. Kissinger trying desperately to extract the US from the war before the Presidential elections of 1972 cables his boss Nixon that he is experiencing difficulties in reaching a final solution. The depiction of the Vietnam War Theme Park, once the site of the Vietcong resistance in the labyrinth of tunnels they dug not thirty kilometres from American military HQ, now a Disneyland of war for visiting tourists who may shoot at a target with a Vietcong or American submachine gun. The pacification plan undertaken by the CIA by flying in toothbrushes and portable flush toilets to villages whose inhabitants lived in medieval poverty. These are the moments when the violence and madness associated with the Vietnam war strikes home, when the evidence and the actions are permitted to speak clearly for themselves.

So is the response to Pilger’s style of documentary filmmaking after all a logical rejection of partiality, of the personal, of committed polemic in favour of the deceptively neutral balance of consensus? I think not. The personal point of view surely lies as much in the passionately crafted argument, in the precisely presented details of a situation as it does in the head-on presentation of the outraged, honest protester.

Pilger’s strength, his courage in presenting himself as the case for the prosecution, is also finally his weakness. After viewing the Vietnam films and his work on Timor, Nicaragua and Cambodia I am clear about what he stands against but not what he stands for. A sense of social justice, human decency, humanitarian notions of protecting the innocent. These are worthy values. They are the middle-class values of the radical conservative. There are times in these films when his rage seems directed against his own inability to change the world and he lashes out at the perfidies without discrimination or coherence: the bombing of Hanoi, the downgrading of free education programs, tourism, the My Lai massacre, economic rationalism, Hollywood war films – they all get a serve. It is as though he recognises that he is embedded in the very system which produces these effects and without a politically radical perspective can only protest at the ruthless progress of the juggernaut in which he, like us, is trapped.

He reminds me of that good man in the Socratic fable who went searching in broad daylight with a lit lamp to discover and illuminate the truth.