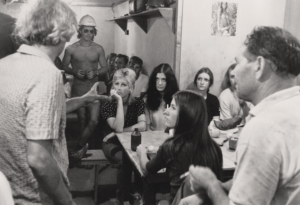

In March 2019, a special screening of the newly digitally restored version of Charles Chauvel’s Sons of Matthew (1949) took place at Home of the Arts (HOTA) on the Gold Coast. The event marked the seventieth anniversary of the film, much of which was shot in nearby hinterland to the west. The evening also included a Q&A between Gayle Lake, senior curator at the National Film and Sound Archive of Australia (NFSA), and Ric Chauvel Carlsson, the grandson of Charles and his wife, Elsa.

This was a fascinating occasion – and not just because it offered the opportunity to view the upgraded version of the film and hear Chauvel Carlsson’s potted history of it. The Q&A was imbued with a pleasant community spirit, as this appeared to be a reunion, of sorts, for local residents with memories of the film being made in the region and its release in cinemas. A couple of nonagenarian women spoke of watching scenes being shot in the small town of Numinbah; a man stood up and revealed that he was the son of the one of the cast members, Tommy Burns; a woman said she was the niece of an actor who played a minor role; another man recalled seeing the film in a Gold Coast cinema over Christmas in 1949. If ever proof were needed that shooting films in regional areas leaves a legacy, this was it.

Sons of Matthew can be regarded as Chauvel’s most personal project. Born in 1897 in Warwick, Queensland, he grew up amid the landscape shown in the film, with parents who faced the struggle and reward of farming this arable land. Therefore, Sons of Matthew might be interpreted, in part, as a paean to his childhood. It also allowed Chauvel to celebrate what we might warily call the ‘common’ Australian man and woman. His previous film, The Rats of Tobruk (1944), a propaganda piece about three drovers who go off to fight in World War I, also did this to an extent.

Chauvel turned fifty in 1947, the year Sons of Matthew went into production.[1]‘Sons of Matthew’, Ozmovies, <https://www.ozmovies.com.au/movie/sons-of-matthew>, accessed 12 November 2019. This was the eighth feature film he would direct in a career that started with the silent films The Moth of Moonbi (1926) and Greenhide (1926) and progressed with In the Wake of the Bounty (1933), Heritage (1935), Uncivilised (1936), Forty Thousand Horsemen (1940) and The Rats of Tobruk. By 1947, therefore, Chauvel had earned himself a substantial reputation that would afford him creative freedom as well as industry relationships that would yield financial support.

To watch Sons of Matthew today is to be struck by its immense ambition, from its elaborate set pieces to its expansive cinematography that elegantly romanticises the Lamington Plateau and surrounds. Furthermore, the legendary difficulties of its making come across palpably, with actors struggling up escarpments and dodging charging brumbies. The film is also significant for the modern viewer as it is, as stated in John Doggett-Williams’ documentary The Big Picture (2014), ‘the only record of a lost landscape’,[2]The Big Picture, special feature, Sons of Matthew, DVD, Umbrella Entertainment, 2014. given the environmental changes in this region over the following decades.

Sons of Matthew does, however, contain several troubling aspects for the twenty-first century viewer, even if the film should be understood as an ideological and social product of its time. Chief among these must be its attitudes towards women, its glorification of what amounts to environmental vandalism and its treatment (or lack of treatment) of Indigenous peoples.

‘A heritage for his country’: The plot

Sons of Matthew opens with a hand turning the pages of what appears to be a family album, introducing us to the main characters. Matthew O’Riordan (John O’Malley), an Irishman, is married to Jane (Thelma Scott), ‘from a gentle village in soft Devon’. With their five sons and two daughters, they live in an unspecified region of New South Wales (NSW) at ‘Deep Creek’, a small homestead with a farm, roughly around the turn of the century. Their neighbours include Jane’s brother Jack Farrington (John Fegan) and the McAllisters, Angus (Robert Nelson) and his wife, whose daughter Cathy (played as a young child by Charmian Young) is frequently at the O’Riordan home due to her mother’s poor health (and subsequent death) and her father’s commitments working the land.

The first section of the film shows the O’Riordan siblings during childhood: happy and pious, though afflicted with poverty and the ravages of drought and bushfire – which ultimately force their uncle to move away. Shane (played as a teenager by Tom Collins), the eldest of the sons, is de facto leader of the household when his father is away mustering or droving, and is established early as a voice of reason and maturity.

The film then jumps to the O’Riordan offspring and Cathy (now played by Wendy Gibb) as young adults. The farm is thriving and romance has blossomed between Cathy and second-oldest O’Riordan son Barney (Ken Wayne); the two are expected to marry. As the family convenes before Christmas, Matthew tells his five sons of a ‘green kingdom’ on high land near where Jack has relocated in Queensland. He urges them to move there, clear the land and settle – a lifetime’s work. They agree, and Cathy and Angus also join the adventure.

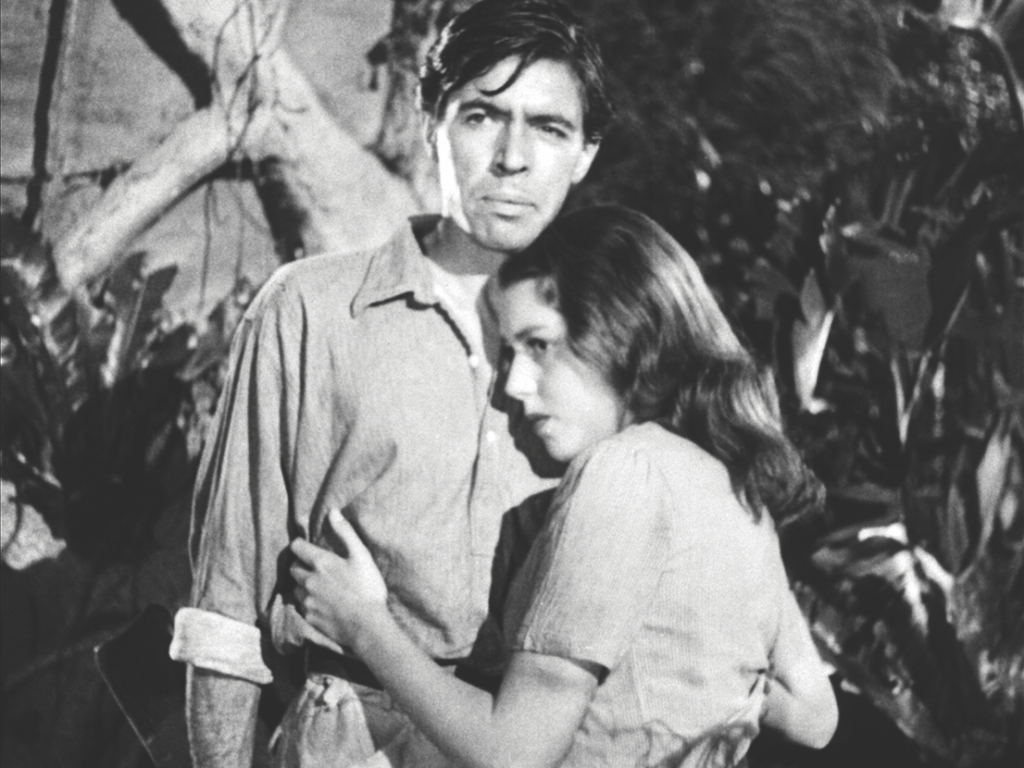

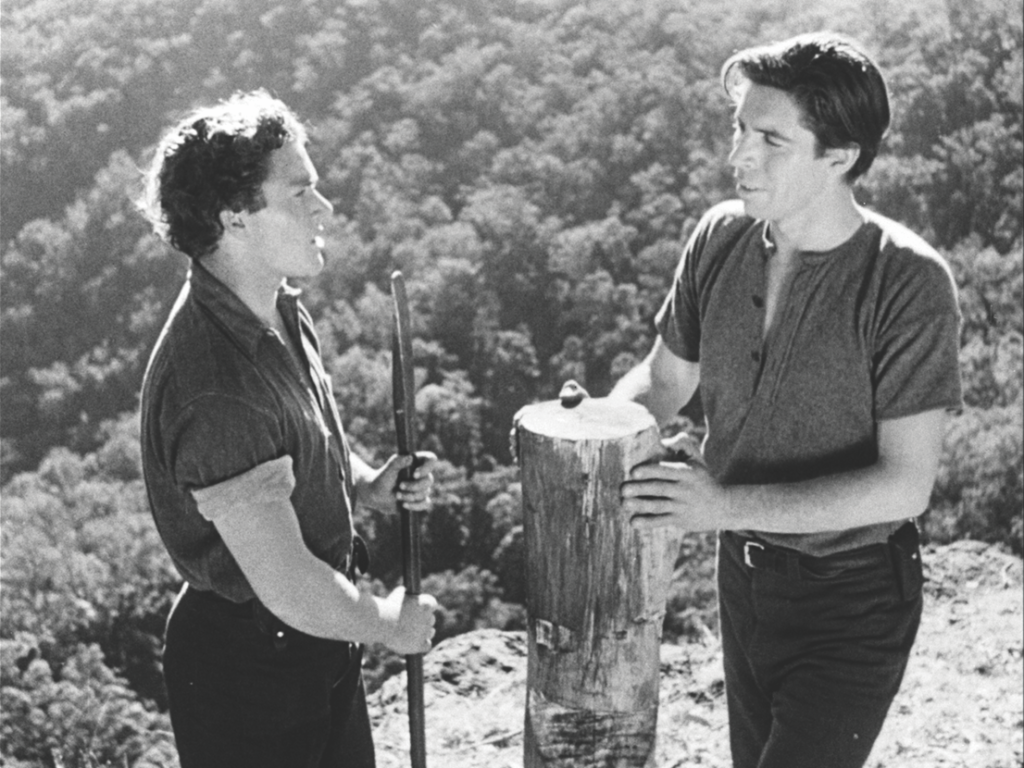

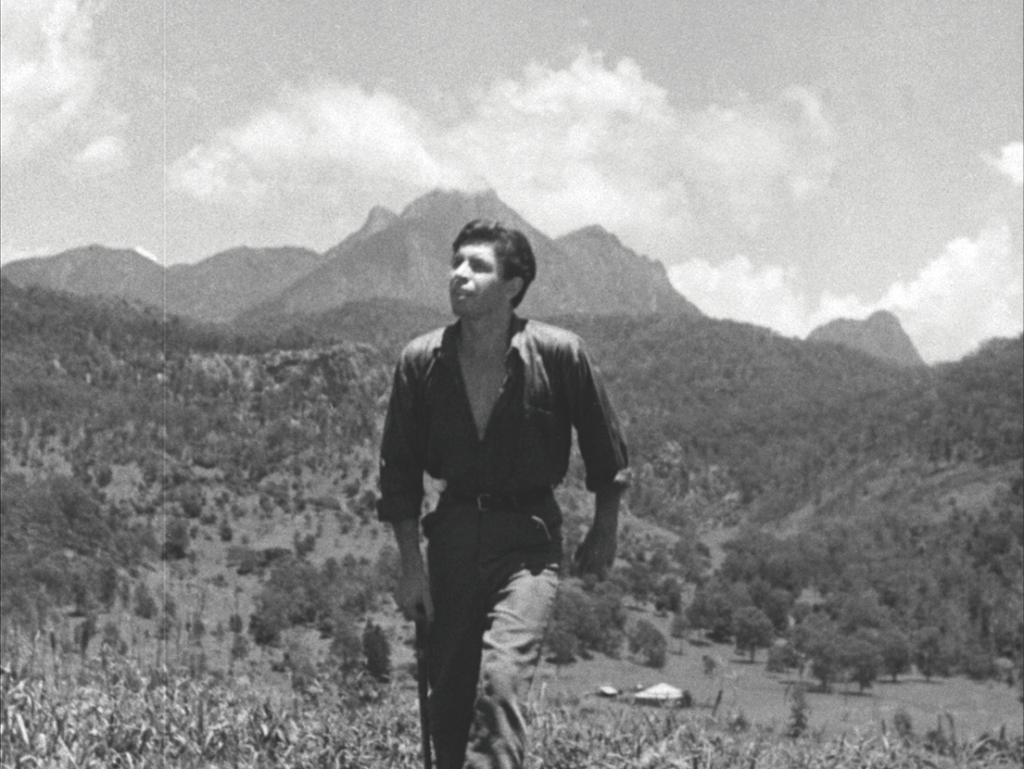

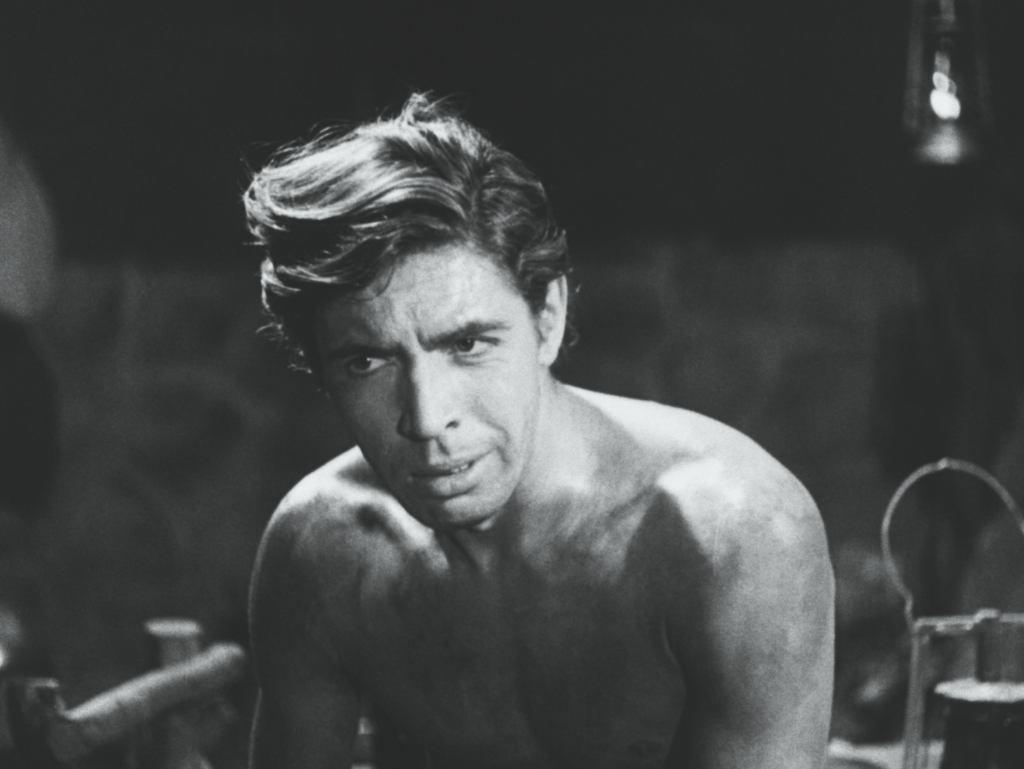

The travelling party head north to south-east Queensland, with its spectacular mountains, waterfalls, rivers and ancient forest. The journey is difficult and exhausting, but they reach their destination and set about cutting down enormous cedars using tiny, primitive axes. Under the direction of Shane (now played by Michael Pate), they eventually establish – after an unspecified period of backbreaking labour – a small cabin and farm. Over time, a bond grows between Shane and Cathy just as Barney’s eye is attracted by a girl, Selina (Cathy Orme), from the nearest village, Patongaville. Work continues at Lamington Plateau as tensions emerge between the five brothers, and Shane and Cathy grow closer. In an important scene, they confess their love for each other when Shane happens upon Cathy after she had been swimming in a creek.

Unimpressed by Barney’s carrying on with Selina, Shane tells his brother of his feelings for Cathy and pledges to ‘take’ her from him. At this point, the rainy season comes, and the farm is hit by a fierce cyclone that threatens to destroy their settlement and puts their lives in danger. Amid the deluge, Cathy gets lost in the bush as she tries to capture cattle that have broken loose, and she falls into a fast-moving creek. Shane is told by Angus where Cathy went, and he eventually finds and rescues her. The pair take shelter in a nearby cave, where they decide to wait out the storm; there, they reaffirm their love for each other.

A bedraggled Barney arrives and interrupts them during an intimate moment. Furious with Shane for his perceived betrayal, he instigates a fistfight, which Shane appears to win, only for Barney to strike Shane with a sucker punch after the elder brother attempts to make peace. Shane is badly hurt with what appears to be a spinal injury. It is revealed that Shane is faced with a long recovery and may not walk again. Jane travels to visit her sons – Matthew has, by now, died – and admonishes Barney for the feud. She urges him to work doubly hard on the land to earn redemption. Barney does so, and eventually Shane recovers enough (he does walk) to approve of his brother’s labours, and the two are reconciled. Shane and Cathy marry, as do Barney and Selina.

The film concludes with the extended O’Riordan clan having a banquet in a large, mansion-like home and being waited on by servants, the voiceover proclaiming, upon reporting Matthew’s death, that he ‘left a heritage for his sons and, in his sons, a heritage for his country’.

Fever dream: The making of

Dengue fever, the viral illness carried primarily by the Aedes aegypti mosquito, is not endemic to Australia. Outbreaks, which are relatively rare, occur only when someone travels to Australia after having been bitten and infected overseas, with the virus spreading when they are bitten in turn by local mosquitoes.[3]See ‘Dengue: Virus, Fever and Mosquitoes’, Queensland Health, 2018, <https://www.health.qld.gov.au/clinical-practice/guidelines-procedures/diseases-infection/diseases/mosquito-borne/dengue/virus-fever>, accessed 11 November 2019. Chauvel was unfortunate enough to have had an encounter with the Aedes aegypti while on location filming his seventh feature film, The Rats of Tobruk, in rainforest near Canungra,[4]‘Charles Chauvel’, Scenic Rim website, <https://www.visitscenicrim.com.au/about-us/pioneering-families/charles-chauvel/>, accessed 12 November 2019. about 70 kilometres south of Brisbane. Chauvel’s case of dengue fever, which manifests flu-like symptoms, was quite severe; he therefore chose to recuperate at a nearby retreat, Binna Burra Lodge.[5]Much of Binna Burra Lodge, including the original building and heritage-listed cabins, was destroyed in bushfires in September 2019. In fact, much of the area in which Sons of Matthew was filmed, including around Numinbah and Canungra, was badly affected. See ‘Gold Coast Hinterland Bushfire Out of Control, Fires Expected to Increase Across Queensland’, ABC News, 9 September 2019, <https://www.abc.net.au/news/2019-09-08/queensland-bushfires-continue-stanthorpe-applethorpe-binna-burra/11489304>, accessed 11 November 2019.

During his convalescence, Chauvel picked up a book, Green Mountains, by Bernard O’Reilly, a local author and pioneer of Irish heritage best known for finding the wreckage and two survivors of the 1937 Stinson plane crash.[6]For more on the crash and O’Reilly, see Jock Given, ‘Enterprise in the Forest’, Meanjin, vol. 76, no. 2, Winter 2017, available at <https://meanjin.com.au/essays/enterprise-in-the-forest/>, accessed 11 November 2019. The 1940 text told the story of its author’s ordeal: of his trekking through the McPherson Range on the border of NSW and Queensland to locate the small aircraft, which was bound for Sydney and crashed en route from Brisbane; and of the extraordinary physical feat of helping the survivors to safety through dense bushland. The book also – and this was crucial for Chauvel – told of O’Reilly and his family’s relocation from the Blue Mountains, west of Sydney, to Queensland’s Lamington Plateau. There, the O’Reillys cleared large stretches of forest and established the O’Reilly Guest House in national park near Canungra (which is still going strong today[7]Now operating as O’Reilly’s Rainforest Retreat, <https://oreillys.com.au>, accessed 11 November 2019.).

Chauvel later read another of O’Reilly’s books, 1944’s Cullenbenbong, about the author’s rugged childhood in the Blue Mountains. A film began to form in the director’s mind that would combine the two books into a single narrative, and which would allow him to indulge two of his signature cinematic preoccupations: a fervent nationalism and his desire to showcase his country’s landscape.

He secured the screen rights to the two books in 1945, beginning a four-year process to bring the film to fruition. Chauvel commissioned radio writers Maxwell Dunn and Gwen Meredith to write a screenplay according to his vision of a combined narrative of Green Mountains and Cullenbenbong, with a specific emphasis on the Stinson rescue. However, this angle soon fell away. With Chauvel and his wife also involved in the writing, the story became one inspired by the O’Reilly family’s settlement on the Lamington Plateau. Chauvel also drew on aspects of his own childhood in the region, and chose to centre his script on five brothers and their efforts to clear and agriculturalise this spectacular subtropical rainforest. Ultimately, the screenplay would be credited to the Chauvels in collaboration with Dunn. By the end of 1946, the film’s plot and characters had been simplified and streamlined, and Sons of Matthew – an ‘epic’ Australian tale of family, land and struggle – was gathering momentum.[8]Andrew Pike & Ross Cooper, ‘Sons of Matthew’, in Australian Film 1900–1977, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1980, pp. 208–9. Financing would be the next step.

Scholars Stuart Cunningham and William D Routt note that the years around World WarII were, for obvious reasons, not the most fecund for Australian film production; they point out, for example, that, of the ten independent features released from 1939 to 1945, only one – The Rats of Tobruk – can be said to have been wholly planned, made and released during this time.[9]Stuart Cunningham & William D Routt, ‘“Fillums Became Films” (1940–1956)’, in Ina Bertrand (ed.), Cinema in Australia: A Documentary History, New South Wales University Press, Sydney, 1989, p. 179. However, some commentators, such as critic Paul Byrnes, believe the war years to be Chauvel’s most successful period;[10]Paul Byrnes, ‘Curator’s Notes’, in ‘Sons of Matthew (1949)’, Australian Screen, <https://aso.gov.au/titles/features/sons-of-matthew/notes/>, accessed 11 November 2019. indeed, they saw the release of Forty Thousand Horsemen, which, as a more jingoistic, chest-beating war film than The Rats of Tobruk, was met with considerable critical and commercial success.

With these films and more behind Chauvel, securing financial investment for Sons of Matthew was not as challenging as it might have been. Certainly, the filmmaker was on surer footing than some of his contemporaries; other directors of the immediate postwar period, such as Ken G Hall, were suffering not only due to a lack of domestic investment in Australian films, but also because of Britain’s decision to restrict imported films – a ‘disaster for Australian producers’, as Hall put it. These constraints even contributed to Greater Union, Australia’s leading exhibitor at the time, eventually ceasing to make features through its subsidiary, Cinesound Productions, with whom Hall had worked since the 1930s.[11]Ken G Hall, Australian Film: The Inside Story, 2nd edn, Summit Books, Sydney, 1980, p. 158.

To overcome this desolate climate, Chauvel turned to a familiar face: Universal Pictures’ Australian head Hercules ‘Herc’ McIntyre, who had been a champion and friend of his since the early 1930s. McIntyre agreed to partially fund the project, and persuaded Norman Rydge of Greater Union to join him in this investment. The Queensland Government also provided funds, as the film would be shot on location on the Lamington Plateau. Chauvel’s track record was the decisive factor in securing finance. As Cunningham has recounted, ‘The […] extraordinary weight of the legend made this possible, for such backing was virtually in the form of “personal confidence” – Chauvel did not even form a production company for the film.’[12]Stuart Cunningham, Featuring Australia: The Cinema of Charles Chauvel, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1991, p. 137.

The budget for Sons of Matthew eventually blew out to an astonishing, unprecedented £120,000, which, as Byrnes notes, was ‘more than twice the budget of other films being made at the time’.[13]Byrnes, ‘Curator’s Notes’, op. cit. Hall’s Smithy (1946), for example, cost £53,000.[14]Hall, op. cit., p. 139. Hall himself, while expressing his admiration for Chauvel, blamed the costs of Sons of Matthew for being another crucial factor in spooking Rydge and Greater Union into shutting down Cinesound Productions after the war. Hall believed that Chauvel was allowed too long a leash for the project and that shooting in the rainforest of Lamington was unnecessary:

There was nothing on the screen in Sons of Matthew which could not have been obtained in the lower Blue Mountains around Kurrajong, the Grose Valley and other areas within a sixty-mile radius of Sydney, where subtropical pockets were readily available.[15]ibid., p. 158.

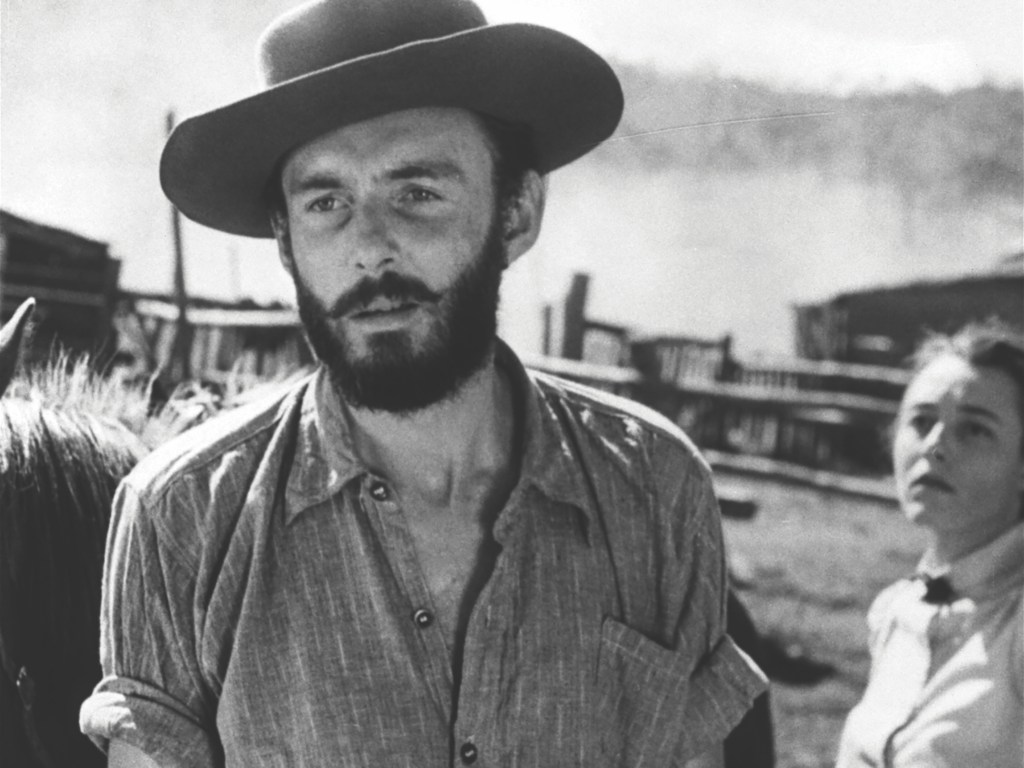

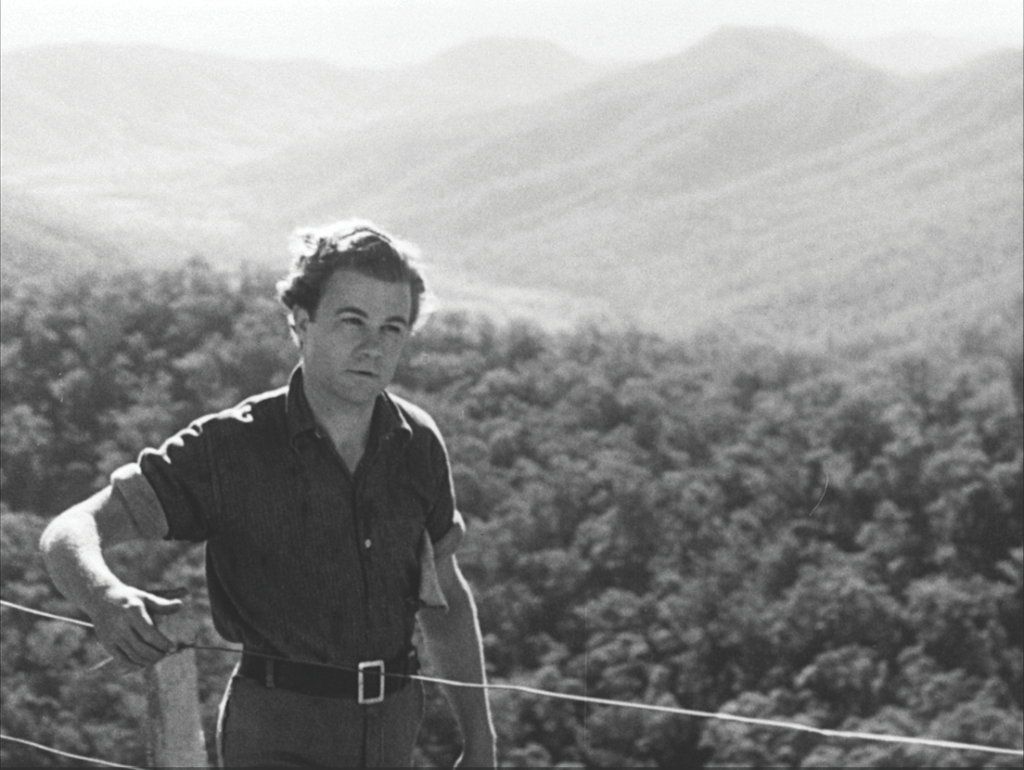

Before departing for the shoot, however, Chauvel was faced with the task of auditioning and casting in Sydney – a process that took months, in part because of Chauvel’s wish to find child actors who looked passably like the adult actor portraying the same character (something never before done in Australian cinema).[16]Cunningham, Featuring Australia, op. cit., p. 149. Pate had worked with Chauvel in Forty Thousand Horsemen, playing multiple small parts. Despite his familiarity with the director, Pate was riddled with nerves on the day of auditioning for the role of Shane, to the point that Chauvel was forced to send him home with instructions to return the next day and try again. Pate won the role on the back of this second performance,[17]Michael Pate, ‘Introduction’, in Susanne Chauvel Carlsson, Charles & Elsa Chauvel: Movie Pioneers, University of Queensland Press, Brisbane, 1989, p. x. and it is fair to say that Sons of Matthew launched him on a career trajectory that saw him enjoy success in both Australia and the US. The inexperienced Gibb, whom Chauvel selected for the part of Cathy, had to postpone plans to travel to England for screen tests to take the role.[18]‘Sons of Matthew: Wendy Gibb to Play Feminine Lead’, Warwick Daily News, 5 February 1947, p. 7. Other castings of note included future children’s-television presenter John Ewart as Mickey; Wayne, who, among many other acting jobs, went on to have an uncredited role in MGM’s The Dirty Dozen (Robert Aldrich, 1967), as Barney; and Scott as O’Riordan matriarch Jane. Chauvel also cast Burns, a champion welterweight boxer, as third O’Riordan son Luke.

In March 1947, a cast and crew of seventy were given a ceremonial farewell by then–Sydney mayor Reg Bartley outside Sydney Town Hall prior to their bus trip to Queensland. As Pate laments in The Big Picture, the weather throughout their journey up the coast was idyllic, only for conditions to turn dramatically for the worse on arrival at the shoot’s headquarters at army barracks near Beaudesert.[19]Michael Pate, in The Big Picture, op. cit. What followed in the ensuing months was, according to Susanne Chauvel Carlsson – daughter of Charles and Elsa, and mother of Ric – ‘an epic of frustration, delay, high costs and a constant battle against the natural elements’, with production on Sons of Matthew coinciding with the ‘wettest period Queensland had seen in over eighty years’, when ‘[f]ifty-five inches of rain fell within ten weeks’.[20]Susanne Chauvel Carlsson, op. cit., p. 136. The cast and crew, which included carpenters, cooks and a teacher for the child actors, became stranded and cut off by the flooding of the Logan River, ensuring this mini-community could neither work on the film nor leave. Soon, the problems went beyond mere filmmaking as food supplies and drinking water ran low and the children became restless. According to Ric Chauvel Carlsson, supplies had to be sent in via flying fox.[21]Ric Chauvel Carlsson, in Sons of Matthew post-screening Q&A, Home of the Arts (HOTA), Gold Coast, 13 March 2019.

The rain persisted for the best part of six months, forcing Chauvel and his crew to completely overhaul their production schedule to take advantage of the tiny windows of opportunity to film allowed by the weather; cinematographer Carl Kayser was crucial in making the production as efficient as possible under these trying circumstances.[22]Susanne Chauvel Carlsson, op. cit., p. 136. Nevertheless, Chauvel had to endure a number of resignations due to the hardships of life on the set.

The mounting costs as a result of the delayed production inevitably made backers McIntyre and Rydge extremely uncomfortable, to the point that they travelled from Sydney to visit Chauvel and check on the film’s progress. One of the most famous anecdotes from Sons of Matthew lore is that Rydge threatened to toss a coin to decide if he would continue to provide financial support. A horrified Chauvel, convinced of the importance of his film and driven by its personal resonance, managed to placate Rydge and McIntyre and continue with the project.[23]Ric Chauvel Carlsson, op. cit.

After six months, the cast and crew left Queensland and returned to Sydney to film at Cinesound, before returning to the Lamington Plateau for a further five months, this time under more clement conditions. This shoot, along with some extra scenes taken in the Blue Mountains, brought Sons of Matthew to completion. The film took eighteen months to shoot and edit – which, according to Byrnes, was ‘almost unheard of in giant Hollywood productions, let alone an Australian film’.[24]Byrnes, ‘Curator’s Notes’, op. cit. Such was the complex and drawn-out nature of the film’s creation that Dunn wrote a book on the subject, 1949’s How They Made Sons of Matthew. (One attendee at the HOTA event stood up to speak brandishing a copy of this book, promising not to lend it to anyone, ever, due to its rarity.)

The film also demanded several dangerous performances from its actors. Gibb was knocked out when a horse reared up on her, and she and Pate were forced to swim in the treacherously icy waters of the Natural Arch waterhole for the cyclone scene.[25]Susanne Chauvel Carlsson, op. cit., p. 136. O’Malley rejected a stunt double in scenes wherein he was charged by a herd of brumbies,[26]Constance Robertson, ‘Sons of Matthew on Location’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 10 April 1947, p. 10. while Ewart is quoted as saying, ‘I didn’t realise I would have to be an athlete, as well as an actor.’[27]John Ewart, quoted in Susanne Chauvel Carlsson, op. cit., p. 136.

Many of the cinematic strengths of Sons of Matthew can be put down to Chauvel’s bloody-minded determination to film in the region around the Lamington Plateau … Wide shots of the plateau and of the Gold Coast hinterland are stunning in various scenes.

Anyone with a belief in omens might have regarded Chauvel’s initial mosquito bite as a sign of things to come, or perhaps even a Tutankhamun-esque curse, for the production of Sons of Matthew. Words to the effect of ‘anything that could go wrong did go wrong’[28]See, for example, The Big Picture, op. cit. are a common refrain in the recollections of many of those involved in the film’s creation. To top off the ordeal, the Chauvels’ Sydney home was reportedly robbed while the film was being made.[29]‘Film Man’s Loss’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 5 February 1949, p. 1.

Sons of Matthew was finally released on 16 December 1949. The international version of the film, renamed The Rugged O’Riordans and shortened by nearly thirty minutes (from 107 minutes to around seventy-eight), was released in the US on 5 January and the UK on 26 January the following year.[30]‘Sons of Matthew’, Ozmovies, op. cit.

At this point, it is essential to recognise the role of Elsa Chauvel in the development and production of this film. Ric Chauvel Carlsson, who is ardent in emphasising her importance to his grandfather’s career, says:

My grandmother had a vital part to play in all this. She was always very respectful and probably didn’t really get in the way on the set, but, after dark around the dinner table, they would discuss the day’s shoot, what could be done better, how the dialogue could be changed and so on. She was a true partner. My grandfather was the visionary producer/director, but my grandmother was the glue that kept things together. She kept him on the straight and narrow; otherwise, he would have gone off on all these different tangents. I don’t think my grandfather could have made his films if it wasn’t for my grandmother.[31]Ric Chauvel Carlsson, op. cit.

Making Australia ‘a film star’: Critiques

Many of the cinematic strengths of Sons of Matthew can be put down to Chauvel’s bloody-minded determination to film in the region around the Lamington Plateau, despite practical and financial difficulties. The word ‘locationism’ has been used by various critics to describe the director’s prioritising of place and landscape over many other filmic concerns; Cunningham, for instance, describes Chauvel’s locationism as an

intense commitment, despite the massive technical and financial obstacles, to shooting the ‘true country’, without implying that it was driven by a coherent documentary aesthetic. The concept of locationism engages with Chauvel’s nationalist desire to make ‘Australia a film star’ […] Locationism was also a major means by which he sought to differentiate his work from the dominant regimes of Hollywood classical cinema.[32]Stuart Cunningham, In the Vernacular: A Generation of Australian Culture and Controversy, University of Queensland Press, Brisbane, 2008, p. 65.

The results of this commitment to the perfect portrayal of landscape are uniquely spectacular in Sons of Matthew. Wide shots of the plateau and of the Gold Coast hinterland are stunning in various scenes – even today, and even in black-and-white. This is a testament to the work of Kayser and fellow cinematographer Bert Nicholas. Moreover, had Chauvel and his backers chosen to shoot the film in the lower Blue Mountains as Hall suggested, many viewers would surely have recognised the familiar sandstone and dense canopies of eucalypts; however, by shooting in Queensland, Chauvel introduced Australian moviegoers to a region that had previously been undocumented on screen. Sons of Matthew was therefore infused with exoticism.

The film’s impressive visuals continue with the scenes of the brothers attempting to fell enormous cedars using their tiny axes and crudely made springboards, the immense girth of the trees at times appearing otherworldly. Through astute camera angles and framing, these tree-felling scenes take the film into what the Umbrella Entertainment DVD notes describe as ‘“King Kong” looking territory’, adding, ‘The men wedged high up the trunk look like ants sawing at an elephant’s leg.’[33]Umbrella Entertainment, ‘Sons of Matthew’, <https://www.umbrellaent.com.au/on-demand/3483-sons-of-matthew-on-demand.html>, accessed 11 November 2019. And Sons of Matthew’s strengths don’t end with striking footage of mountains and forest. The film’s first thirty minutes, when we are with Matthew, Jane and their children at Deep Creek, are its most moving part; in contrast to the melodrama that comes when the action moves to the plateau, these earlier moments of domesticity and intimacy have a humility and softness to them that the film loses once the ‘pioneering’ journey gets into full swing.

With the family bedevilled by poverty, it’s difficult not to be affected by the scenes of baby Cathy being bathed by Jane and Shane; by the children racing a pair of turtles across the floor of their home (with ‘Ned Kelly’ and ‘Angus’ painted on their respective shells); and, especially, by Shane and Barney (played in childhood by Max Lemon) staying up late on Christmas Eve to make toys for their younger brothers and sisters because the family is too poor to afford any other presents.

In this first section of the film, we also see the effects of drought, bushfire and destitution on children – an issue strongly relevant in Australia today.[34]A February 2019 report by the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) Australia entitled In Their Own Words found that children in rural areas are not receiving the required support amid long-term drought conditions; see Patrick Wood, ‘UNICEF Combines Drought Stories of Country Kids to Warn of Worsening Rural Stress’, ABC News, 19 February 2019, <https://www.abc.net.au/news/2019-02-19/drought-kids-in-crisis-rural-issues-unicef/10820748>, accessed 12 November, 2019. The O’Riordan sons are distraught at the prospect of having to sell their beloved pony, Sonny, with Chauvel explicitly targeting the viewer’s heart with close-ups of small, teary faces. There is also a dramatic bushfire sequence that culminates in what is perhaps the most memorable scene of Sons of Matthew: Jane and her children wading into the middle of their dam to escape the fire, their faces lit by the flames as they stand in the water watching the bush burning around them.

Throughout the Deep Creek section, the strongest acting comes from Scott, who adroitly portrays Jane’s juggling of motherly and wifely duties alongside the challenges of a harsh environment. Scott’s delivery is smoother, sadder and more human than that of the slightly wooden O’Malley as Matthew. As she fades out of the film when the O’Riordans and McAllisters travel north, the baton of soulful acting is passed on to Gibb as Cathy, particularly in scenes alone with Shane and in the moment on the plateau when her engagement to Barney is confirmed – much to her unspoken but obvious disappointment. The rest of the performances are merely serviceable, though praise should go to John Unicomb as Terry, a quietly charismatic presence; despite his character being a peripheral figure throughout, Unicomb does plenty with not very much.

While Sons of Matthew is never boring, it does present several deficiencies in its storytelling and structure. A number of jarring narrative shortcuts are taken. Among the most awkward of these must be when Barney suddenly appears in the remote cave where Shane and Cathy have sought shelter during the cyclone; Barney was nowhere to be seen earlier in this sequence, nor was he presented previously as seeking out the two lovers. Here, the screenwriters flirt with the boundaries of plausibility in order to set up the pivotal fight scene in the cave.

Another odd, incongruous scene is a fistfight that occurs in a Patongaville pub between the brothers and some of the local men irritated by Barney’s bragging. There is barely any build-up or foreshadowing for this scuffle; neither the bar nor the other men have appeared before, and the flashpoint – Barney’s involvement with two women – seems dubious cause for a destructive and violent brawl involving dozens of men. The fight and its aftermath serve no narrative function and it is not choreographed with any particular skill or grace – although there is some physical comedy in the combatants lurching in and out of the bar-room doors onto the street as they are pummelled. Pate has said that Chauvel was ‘primarily an action director’,[35]Pate, in The Big Picture, op. cit. while Byrnes notes that, for some critics, he was even known as a ‘B-grade action director’.[36]Paul Byrnes, ‘Charles Chauvel’, Australian Screen, <https://aso.gov.au/people/Charles_Chauvel/portrait/>, accessed 11 November 2019. This fight scene feels like a gratuitous (though understandable) move to inject some of this ‘action’ into Sons of Matthew in the name of entertainment and meeting the expectations of moviegoers at the time. It also afforded an opportunity for Burns, the professional pugilist, to demonstrate his skills.

A further flaw in the storytelling framework of Sons of Matthew (for the modern viewer, at least) is that some dialogue is purely and overtly expository – particularly from the male leaders of the O’Riordan clan, Matthew and Shane, as they explain their motivations and plans to the others. Furthermore, the film’s voiceover, predominantly at the beginning and the end, is delivered with the static detachment of a wartime newsreel. Indeed, Cunningham cites a review of Sons of Matthew that derides the narrating voiceover for being ‘as creakingly old-fashioned as the captions in The Birth of a Nation [DW Griffith, 1915]’.[37]Cunningham, Featuring Australia, op. cit., p. 150.

That disturbing film has, thankfully, little in common with Sons of Matthew, but there are intriguing comparisons to be made with other works. Some critics have cited the films of John Ford as a strong touchstone for Chauvel, with particular comparison drawn between Sons of Matthew and How the West Was Won (co-directed with Henry Hathaway & George Marshall, 1962).[38]See, for example, Umbrella Entertainment, op. cit. Despite the thirteen years between them – other Ford works that may have directly influenced Sons of Matthew include his adaptation of John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath (1940), How Green Was My Valley (1941) and My Darling Clementine (1946) – the two films do have similarities. For one, they share the themes of nation-building, pioneering, settlement, family and patriotic heroism, to name a few. A comparison of the voiceovers that end the two films also illustrates their common ground: in How the West Was Won, the narrator (Spencer Tracy) says, ‘Out of the hard simplicity of their lives, out of their vitality, their hopes, their sorrows, grew legends of courage and pride to inspire their children and their children’s children,’ which has strong echoes of the aforementioned spoken epilogue at the conclusion of Sons of Matthew.

Another American director of the period with whom Chauvel appears to have a stylistic and thematic kinship is Frank Capra (born five months before Chauvel in 1897). As I watched Sons of Matthew for the first time, the film that immediately came into my mind was Capra’s Lost Horizon (1937), with its similarly lavish shots of lush, mountainous vistas (shot in south-western USA); such sweeping cinematography characterises both pictures. Lost Horizon is a fantasy work with various supernatural elements based around the mystical Himalayan paradise of Shangri-La, but the idea of a mysterious, bounteous promised land that has an intoxicating effect on its visitors is obviously germane when considering Sons of Matthew. Chauvel might be regarded as the ‘Australian John Ford’, but we can also consider him the ‘Australian Frank Capra’, especially given that many of Capra’s films, such as Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939) and Meet John Doe (1941), valorise idealism, patriotism and individualism. Certainly, Sons of Matthew has all of these things in spades.

A ‘new Israel’

The title ‘Sons of Matthew’ has clear biblical overtones and frames the brothers’ odyssey and hard work in terms of a religious crusade or even a pilgrimage. The film also begins with a captioned quote from the Gospel of Matthew: ‘And the rain descended, and the floods came, and the winds blew, and beat upon that house; and it fell not: for it was founded upon a rock.’[39]Matthew 7:25 (King James Version), available at BibleHub, <https://biblehub.com/matthew/7-25.htm>, accessed 11 November 2019. In the wake of this, the sons are not only the literal sons of Matthew O’Riordan but the acolytes of this ideal: of standing one’s ground on sure footing in the face of nature’s onslaught. (There is also a tale in Matthew told by Jesus, ‘The Parable of the Two Sons’, that may have been in Chauvel’s mind.)

The title ‘Sons of Matthew’ has clear biblical overtones … the sons are not only the literal sons of Matthew O’Riordan but the acolytes of this ideal: of standing one’s ground on sure footing in the face of nature’s onslaught.

Australian-cinema scholar Tom O’Regan has expanded on the Christian elements of Sons of Matthew, emphasising how the film features an interfaith marriage – which is never alluded to or commented on – between an Irish Catholic (Matthew) and an English Protestant (Jane). In suggesting that the Lamington Plateau and Australia generally are a new Eden, Chauvel presents a nation in which any sectarian divides are overwhelmed by a new identity: the Australian Christian, which all of the O’Riordan children become. Australia is, therefore, a ‘new Israel’. According to O’Regan,

Sons of Matthew provides one of the first expressions of a truce in the sectarian/ethnic conflicts between Irish (a working-class minority) and English (the middle-class majority) with the Scots [Angus and Cathy McAllister], as ever, somewhere in between the two. Australia becomes the new Israel in another sense: the bitter ethnic and nationalist conflicts of the British Isles are ‘resolved’ in Australia by being made matters of family and blood. The culturally Christian Anglo-Celt succeeds a diasporic sense of Britishness.[40]Tom O’Regan, Australian National Cinema, Routledge, London & New York, 1996, p. 275.

In the context of O’Regan’s analysis, it is also interesting to note that in 1949 – the year Sons of Matthew was released – the federal Nationality and Citizenship Act 1948 came into effect, allowing for the option to legally become an Australian citizen (as distinct from a British subject).[41]See Michael Klapdor, Moira Coombs & Catherine Bohm, ‘Australian Citizenship: A Chronology of Major Developments in Policy and Law’, Parliament of Australia, <https://www.aph.gov.au/About_Parliament/Parliamentary_Departments/Parliamentary_Library/pubs/BN/0910/AustCitizenship>, accessed 11 November 2019.

In contrast, film scholar Chelsea Barnett sees the apparent unity between the Irish and the British in Sons of Matthew in a less progressive light. The ‘congruence’ between the two nationalities is an attempt to expunge from history the Irish contribution to colonisation, absorbing Irish pioneering in Australia into the wider, wholly British project – conveniently ignoring the historical antagonism between the two peoples. ‘The representation of Irishness in Sons of Matthew erases any memories of conflict with the British, or any recognition of Irishness as distinct from Britishness,’ argues Barnett, going on to say that it

provides no space in which the conflict between the Irish and the British can be shown or even suggested […] Rather, the film represents the past as a space in which British male pioneers successfully overcame the obstacles of the landscape.[42]Chelsea Barnett, Reel Men: Australian Masculinity in the Movies 1949–1962, Melbourne University Publishing, Melbourne, 2019, pp. 42–3.

This is a compelling point, and one supported by various aspects of the film. For example, it is Matthew, the Irish father, who dies while Jane, the English mother, lives on to witness the sons’ triumph. In addition, a survey of the O’Riordan children’s accents reveals Irishness being phased out: Shane and Terry, the two most articulate sons, speak with what is essentially their mother’s English accent, while Barney, Luke and Mickey speak with a mild but recognisable Australian twang. None of the O’Riordan children have inherited any hint of their father’s Irish accent or vernacular, a factor supporting Barnett’s thesis.

‘No place for a woman’

It would be unfair on Chauvel and everyone else involved in Sons of Matthew – and, indeed, critically redundant – to dismiss outright this remarkable piece of cinema on the basis of some elements that jar with our modern-day sensibilities and collectively evolving moral compass. But these problems are nevertheless worth addressing, as they illuminate how our values and expectations of cinema have changed since 1949; they also reveal aspects of the colonial and/or settler mindset, which continues to be deconstructed and dismantled today.

Arguably the most glaring issue for contemporary viewers would be the film’s depictions of attitudes towards women. Much of its sexism is explicit and occasionally awful, and most of it comes through the character of Shane (although Barney offers his fair share of chauvinism as well). Shane’s catalogue of sexist dialogue begins when he declares that Cathy needs ‘putting over someone’s knee’ for riding too fast on a horse. He also remarks that the plateau will be ‘no place for a woman’, and he and Barney discuss how the jungle is ‘like a beautiful woman: lovely to look at but tough to handle’. Most shocking, though, is Shane’s equating of women and livestock in a conversation with Barney: ‘When the O’Riordan brand goes on a girl, it goes on clean.’

Shane also remarks to Cathy, ‘Women and the earth, I’ve always thought they’re much the same, only the earth’s more exciting,’ reflecting the film’s strong alignment of women (or, at least, Cathy) with the natural landscape. For Shane, both must be tamed, owned, maximised (‘You’re going to be my wife and bear my sons because that’s the way it was meant to be,’ he barks at Cathy in the cave) and kept in check. Just as the forest can bite back at his clearing efforts with new growth and must be quelled, women must be controlled with a ‘firm hand’.

Another noticeable instance of misogyny occurs when the narrator is introducing characters at the beginning and has to backpedal after admitting he had forgotten to mention the O’Riordan daughters, Rose (Dorothy Alison) and Mary (Diane Proctor). As the film unfolds, we watch as these barely seen daughters are duly sent away from the room whenever something ‘serious’ must be discussed.

‘A place where no man’s been before’

After Matthew has told the family about the ‘green kingdom’ on offer in Queensland, Shane responds, ‘There’s something good about cutting into a place where no man’s been before.’ There is a glint in Shane’s eye as he says this, reflecting his impassioned desire to possess, to exploit, to control nature for economic gain – and to be the first man to penetrate virgin rainforest. For today’s viewer, Sons of Matthew is surely troubling in its approach to the environment and ecology. The tree-felling scenes, in particular, make for uneasy viewing given the current ongoing deforestation of Australia[43]See Michael Slezak, ‘“Global Deforestation Hotspot”: 3m Hectares of Australian Forest to Be Lost in 15 Years’, The Guardian, 5 March 2018, <https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2018/mar/05/global-deforestation-hotspot-3m-hectares-of-australian-forest-to-be-lost-in-15-years>, accessed 11 November 2019. and the environmental crises, including climate change, associated with this. The footage of giant cedars being hacked into and ultimately falling are, despite the impressive scale of everything, ugly and distressing.

Shane’s maniacal need to ‘clear’ these ancient trees reflects a colonial impulse that is touched on by Australian writer Sophie Cunningham in her recent book City of Trees. Attempting to humanise trees and bridge the separation between humanity and the rest of nature – a separation the men of Sons of Matthew reinforce in their ongoing bid for territory and property – she writes:

A tree is never just a tree. It speaks of the history of the place where it has grown or been planted: the hills that were dynamited, the creeks that were concreted, the water that has been drained to give it a place to root. Trees speak of the displacement of first nations. Of the endless lust of governments (small and large) to control places and the ways in which trees should or should not grow, the ways in which humans should or should not live.[44]Sophie Cunningham, City of Trees: Essays on Life, Death and the Need for a Forest, Text Publishing, Melbourne, 2019, p. 7.

In many ways, Sons of Matthew is a celebration of colonists’ control over the environment and how trees ‘should or should not grow’. For Shane, deforestation demonstrates the power of his will over nature; he might even regard trees as a kind of enemy, a foe to be vanquished. Sophie Cunningham would regard this attitude as part of the settler mindset; in a recent interview, she suggests that

trees stood in the way of agriculture in secular society. There was a sense that you had to remove trees to bring in sheep and grow fields […] and I think it was partly because for those of us who came from England the trees were very ‘other’ [… and] it didn’t seem like they were ‘real’ trees: they looked weird.[45]Sophie Cunningham, quoted in Katinka Smit, ‘Notes from the Festival: Sophie Cunningham’, Northerly, Spring 2019, p. 15.

The trees are certainly ‘other’ to Shane. And, while his dream of clearing the rainforest might be presented in romantic terms as his life’s ‘purpose’, we can identify him as having an attachment to the land that is characteristic of the colonising Australian: a strong, emotional, almost spiritual bond, yet one that holds no qualms about mutilating it. In fact, today, the character of Shane comes across as a sexist, a killjoy, a fusspot and a crashing bore – only the softness of Pate’s acting makes him relatable or vulnerable.

The final scene of the film is discomforting. The O’Riordan clan, by now expanded with wives and children, sits triumphantly around a large dining table in an enormous house built on the plateau while servants wait on them as if they were some kind of royal family – the conquerors of the wilderness. The goal of property and dominion is achieved. The ending also shows acres of cleared land and cattle; the once-dense rainforest has been transformed into paddocks that, in being adapted for farming and agriculture, now distinctly resemble the English countryside.

A ‘great and ugly silence’

Sons of Matthew features just one reference to an Aboriginal person: Terry mentions a ‘black fellow’ carrying a message from Patongaville to the plateau. Any omissions regarding Indigenous peoples in Sons of Matthew can be understood in the context of Chauvel’s intentions: telling a story of such personal relevance that celebrated the Christian pioneer left little room for engagement with the Aboriginal presence on the landscape. Let’s also not forget that Chauvel’s next film was the iconic Jedda (1955), his cinematic contribution to the debate about assimilation. Though there is almost no reference to Indigenous individuals in Sons of Matthew, perhaps Chauvel cannot be accused generally of being unmindful of them.

Any omissions regarding Indigenous peoples in Sons of Matthew can be understood in the context of Chauvel’s intentions: telling a story of such personal relevance that celebrated the Christian pioneer left little room for engagement with the Aboriginal presence on the landscape.

Yet this absence does compromise the picture overall. O’Regan describes the film as Chauvel’s attempt to create a ‘foundation myth’ for Australia[46]O’Regan, op. cit., p. 274. – a creation story, if you will, for settlement and pioneering. A similar term, ‘origin story’, is used by contemporary novelist Christos Tsiolkas – in relation to the 1955 Patrick White novel The Tree of Man – in his book On Patrick White. In the novel, protagonist Stan Parker clears a patch of bushland and builds a small house; he marries Amy, raises a family and oversees a farm. The book, in its way an existential masterpiece, follows Stan and Amy’s life together as they are buffeted by nature as well as the complications and resentments of their relationships. Tsiolkas believes The Tree of Man to be among the greatest novels of the twentieth century, yet he remarks that a lack of an Aboriginal component in this ‘origin story’ can detract from its merits:

There is an argument to be had that in ignoring that central condition of being Australian – the relationship and the history of the Aborigine and the settler – White maintained the great and ugly silence about race relations in our country.[47]Christos Tsiolkas, On Patrick White, Black Inc., Melbourne, 2018, p. 34.

This comment can be applied directly to Chauvel and Sons of Matthew. In not acknowledging any Indigenous presence or history on the land being cleared, which the brothers clearly believe to be terra nullius, the film perpetuates a similar ‘great and ugly silence’. It is, however, worth noting that White, like Chauvel with Jedda, subsequently went on to address the Aboriginal experience in the 1961 novel Riders in the Chariot and, to a lesser extent, 1957’s Voss.

The Tree of Man was the other artwork (along with Capra’s Lost Horizon) to come into my mind upon viewing Sons of Matthew for the first time. The two works make for intriguing companion texts (or, indeed, counter-texts). Whereas Sons of Matthew might be seen as a nostalgic tribute to the heroes of pioneering, leaving its audience in no doubt as to where their allegiances are being directed and what constitutes a happy ending, The Tree of Man offers a more ambiguous meditation on the experience of settlement. The White novel asks questions, on a cosmic or even ‘spiritual’ level, around what procuring land and property ultimately amounts to – and, if it’s to nothing, in the grander scheme of things, what else might give meaning to European-settler lives. To return to The Tree of Man after Sons of Matthew is a refreshing counterbalance after the film’s unequivocal embrace of capitalism.

‘Simple grandeur’: Reception

Sons of Matthew did reasonably well at the box office in Australia, making more than £50,000[48]‘What Killed Our Film Industry?’, The Sunday Mail, 17 February 1952, p. 11. (nowhere near breaking even, given the £120,000 budget, but still very respectable by the standards of this postwar period) and reportedly being seen by 750,000 people.[49]F Keith Manzie, ‘Pioneer Spirit Inspired Australian Film’, The Argus, 19 May 1950, p. 9. Overseas, The Rugged O’Riordans fared less well, but, according to Susanne Chauvel Carlsson, it still made a ‘comfortable profit’ in the UK and USA.[50]Susanne Chauvel Carlsson, op. cit., p. 136. That said, the film did have the ignominy of being withdrawn from a cinema in New York after just eight days.[51]‘Australian Film Fails in U.S.’, The Mercury, 16 January 1950, p. 4. This would not have been helped by a brutal review from The New York Times critic Bosley Crowther, who branded the film ‘a dismally disappointing effort, cut along the most crude and conventional lines’ and lambasted its dialogue as ‘fustian’.[52]Bosley Crowther, ‘The Screen in Review; Dream No More, Story About Israel in Documentary-type Picture, of Ambassador at the Park Avenue at the Palace’, The New York Times, 6 January 1950, p. 25, available at <https://www.nytimes.com/1950/01/06/archives/the-screen-in-review-dream-no-more-story-about-israel-in.html>, accessed 11 November 2019.

Reviews in the UK were mixed. The Evening News advised Chauvel to ‘rely less on hardy formulas’ and questioned the authenticity of ‘pioneers talking like the young ladies and gentlemen in the West End’. The Evening Standard praised the photography and the ‘simple grandeur’ of Chauvel’s filmmaking, but criticised the acting of Pate, Wayne and Gibb as the love-triangle protagonists. The Daily Mail made a similar point, praising the scenes of tree-felling, but comparing the acting to the ‘well-meaning earnestness of amateurs enjoying their annual week at the local playhouse and determined to give their all or bust’.[53]All cited in ‘What London Says of Matthew’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 28 January 1950, p. 3. On the other hand, its popularity in the UK was boosted by a promotional competition with a prize of passage to Australia and funds to purchase land or property.[54]‘Gossip from the Studios’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 30 November 1950, p. 17. Furthermore, the British Film Institute bestowed on The Rugged O’Riordans the honour of a request of a copy for its archives for posterity.[55]‘Australian Film “for Posterity”’, The Advertiser, 7 October 1950, p. 15.

Domestic reviews were more positive, particularly in regional newspapers. The South Coast Express, The Daily Advertiser, The South Coast Bulletin and The Mercury were all effusive in their praise. Sydney paper The Daily Telegraph’s review was complimentary about the film’s technical prowess and acting (particularly those of Pate and Wayne) but found fault with its editing and voiceover commentary.[56]Josephine O’Neill, ‘Sons of Matthew’, The Daily Telegraph, 18 December 1949, p. 51. The Australian Women’s Weekly praised the film’s visual aspects and Pate’s performance, but took issue with its ‘indefiniteness’ and continuity: ‘The story emerges as a series of loosely linked episodes rather than a slice of dramatic reality.’[57]MJ McMahon, ‘Talking of Films’, The Australian Women’s Weekly, 31 December 1949, p. 32. Perhaps the only outright-damning Australian review came from The Sunday Herald, which pilloried the plot, dialogue and acting.[58]Lindsey Browne, ‘Reviews of New Films’, The Sunday Herald, 18 December 1949, p. 36.

More recent readings of Sons of Matthew, such as those from Stuart Cunningham, O’Regan and Barnett, draw attention to its colonial, religious and gender-based aspects, positioning it as a cultural artefact that affords insight into Australian ideals and values during the postwar period. Ecological criticism of the film is also recent; writing for Senses of Cinema in 2011, Andrew Katsis contends:

Today’s more environmentally aware audiences will cringe as the O’Riordans’ axes bring centuries-old cedars thundering to the ground, but Chauvel is nevertheless able to imbue this moment with a sort of religious mysticism […] With every blow of the axe, Man becomes closer to God.[59]Andrew Katsis, ‘“You and the Earth, Cathy. That’s All I Want.” Sons of Matthew (Charles Chauvel, 1949)’, Senses of Cinema, issue 58, March 2011, <http://sensesofcinema.com/2011/key-moments-in-australian-cinema-issue-70-march-2014/you-and-the-earth-cathy-thats-all-i-want-sons-of-matthew-charles-chauvel-1949/>, accessed 11 November 2019.

The reviews of Sons of Matthew that appeared in the immediate wake of its release show that it was hardly regarded as an instant classic. And, today, the film is not a household name. However, the HOTA screening proved that it is still popular in south-east Queensland, at least, while the NFSA’s digital restoration ensures that it will endure into the future with deserved prestige.

Despite Sons of Matthew’s being flawed in several ways – and those flaws have accumulated as the paradigms of criticism have evolved with culture – it is a relic worth valuing, and not just for its celebrated landscape cinematography. For historians, the film is illuminating in its portrayal of the pioneering ethos, however simplified for cinema it might be. As well, the spectacularly arduous saga of its creation should not be forgotten. Indeed, the Umbrella Entertainment notes go as far as to say that the project’s journey to the screen is worth ‘a feature in itself rather like Burden of Dreams [Les Blank, 1982] is to Fitzcarraldo [Werner Herzog, 1982]’.[60]Umbrella Entertainment, op. cit.

Perhaps the film’s lengthy and laboured production could even serve as a ‘foundation myth’ for Australian cinema – a legendary tale of ambition and struggle to break new ground. ‘[Australian] filmmakers today need to respect our pioneers,’ said Ric Chauvel Carlsson at HOTA, ‘and what they went through to leave something for others to pick up on.’[61]Ric Chauvel Carlsson, op. cit.

This article has been refereed.

Select bibliography

Chelsea Barnett, Reel Men: Australian Masculinity in the Movies 1949–1962, Melbourne University Publishing, Melbourne, 2019.

The Big Picture, special feature, Sons of Matthew, DVD, Umbrella Entertainment, 2014.

Paul Byrnes, ‘Curator’s Notes’, in ‘Sons of Matthew (1949)’, Australian Screen, <https://aso.gov.au/titles/features/sons-of-matthew/notes/>.

Susanne Chauvel Carlsson, Charles & Elsa Chauvel: Movie Pioneers, University of Queensland Press, Brisbane, 1989.

Stuart Cunningham, Featuring Australia: The Cinema of Charles Chauvel, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1991.

Stuart Cunningham, In the Vernacular: A Generation of Australian Culture and Controversy, University of Queensland Press, Brisbane, 2008.

Stuart Cunningham & William D Routt, ‘“Fillums Became Films” (1940–1956)’, in Ina Bertrand (ed.), Cinema in Australia: A Documentary History, New South Wales University Press, Sydney, 1989.

Ken G Hall, Australian Film: The Inside Story, 2nd edn, Summit Books, Sydney, 1980.

Andrew Katsis, ‘“You and the Earth, Cathy. That’s All I Want.” Sons of Matthew (Charles Chauvel, 1949)’, Senses of Cinema, issue 58, March 2011, <http://sensesofcinema.com/2011/key-moments-in-australian-cinema-issue-70-march-2014/you-and-the-earth-cathy-thats-all-i-want-sons-of-matthew-charles-chauvel-1949/>.

Tom O’Regan, Australian National Cinema, Routledge, London & New York, 1996.

Andrew Pike & Ross Cooper, ‘Sons of Matthew’, in Australian Film 1900–1977, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1980.

Umbrella Entertainment, ‘Sons of Matthew’, <https://www.umbrellaent.com.au/on-demand/3483-sons-of-matthew-on-demand.html>.

MAIN CAST

Shane O’Riordan Michael Pate Cathy McAllister Wendy Gibb Barney O’Riordan Ken Wayne Jane O’Riordan Thelma Scott Matthew O’Riordan John O’Malley Luke O’Riordan Tommy Burns Terry O’Riordan John Unicomb Mickey O’Riordan John Ewart Jack Farrington John Fegan Angus McAllister Robert Nelson Selina Benson Betty Orme

PRINCIPAL CREDITS

Year of release 1949 Length 107 mins Director/Producer Charles Chauvel Associate Producer Elsa Chauvel Writers Charles Chauvel, Elsa Chauvel & Maxwell Dunn Funding and support Universal International Pictures, Greater Union Theatres & Queensland Government Directors of Photography Bert Nicholas & Carl Kayser Sound Allyn Barnes & Clive Cross Editor Terry Banks Art Director George Hurst Music Henry Krips

Endnotes

| 1 | ‘Sons of Matthew’, Ozmovies, <https://www.ozmovies.com.au/movie/sons-of-matthew>, accessed 12 November 2019. |

|---|---|

| 2 | The Big Picture, special feature, Sons of Matthew, DVD, Umbrella Entertainment, 2014. |

| 3 | See ‘Dengue: Virus, Fever and Mosquitoes’, Queensland Health, 2018, <https://www.health.qld.gov.au/clinical-practice/guidelines-procedures/diseases-infection/diseases/mosquito-borne/dengue/virus-fever>, accessed 11 November 2019. |

| 4 | ‘Charles Chauvel’, Scenic Rim website, <https://www.visitscenicrim.com.au/about-us/pioneering-families/charles-chauvel/>, accessed 12 November 2019. |

| 5 | Much of Binna Burra Lodge, including the original building and heritage-listed cabins, was destroyed in bushfires in September 2019. In fact, much of the area in which Sons of Matthew was filmed, including around Numinbah and Canungra, was badly affected. See ‘Gold Coast Hinterland Bushfire Out of Control, Fires Expected to Increase Across Queensland’, ABC News, 9 September 2019, <https://www.abc.net.au/news/2019-09-08/queensland-bushfires-continue-stanthorpe-applethorpe-binna-burra/11489304>, accessed 11 November 2019. |

| 6 | For more on the crash and O’Reilly, see Jock Given, ‘Enterprise in the Forest’, Meanjin, vol. 76, no. 2, Winter 2017, available at <https://meanjin.com.au/essays/enterprise-in-the-forest/>, accessed 11 November 2019. |

| 7 | Now operating as O’Reilly’s Rainforest Retreat, <https://oreillys.com.au>, accessed 11 November 2019. |

| 8 | Andrew Pike & Ross Cooper, ‘Sons of Matthew’, in Australian Film 1900–1977, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1980, pp. 208–9. |

| 9 | Stuart Cunningham & William D Routt, ‘“Fillums Became Films” (1940–1956)’, in Ina Bertrand (ed.), Cinema in Australia: A Documentary History, New South Wales University Press, Sydney, 1989, p. 179. |

| 10 | Paul Byrnes, ‘Curator’s Notes’, in ‘Sons of Matthew (1949)’, Australian Screen, <https://aso.gov.au/titles/features/sons-of-matthew/notes/>, accessed 11 November 2019. |

| 11 | Ken G Hall, Australian Film: The Inside Story, 2nd edn, Summit Books, Sydney, 1980, p. 158. |

| 12 | Stuart Cunningham, Featuring Australia: The Cinema of Charles Chauvel, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1991, p. 137. |

| 13 | Byrnes, ‘Curator’s Notes’, op. cit. |

| 14 | Hall, op. cit., p. 139. |

| 15 | ibid., p. 158. |

| 16 | Cunningham, Featuring Australia, op. cit., p. 149. |

| 17 | Michael Pate, ‘Introduction’, in Susanne Chauvel Carlsson, Charles & Elsa Chauvel: Movie Pioneers, University of Queensland Press, Brisbane, 1989, p. x. |

| 18 | ‘Sons of Matthew: Wendy Gibb to Play Feminine Lead’, Warwick Daily News, 5 February 1947, p. 7. |

| 19 | Michael Pate, in The Big Picture, op. cit. |

| 20 | Susanne Chauvel Carlsson, op. cit., p. 136. |

| 21 | Ric Chauvel Carlsson, in Sons of Matthew post-screening Q&A, Home of the Arts (HOTA), Gold Coast, 13 March 2019. |

| 22 | Susanne Chauvel Carlsson, op. cit., p. 136. |

| 23 | Ric Chauvel Carlsson, op. cit. |

| 24 | Byrnes, ‘Curator’s Notes’, op. cit. |

| 25 | Susanne Chauvel Carlsson, op. cit., p. 136. |

| 26 | Constance Robertson, ‘Sons of Matthew on Location’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 10 April 1947, p. 10. |

| 27 | John Ewart, quoted in Susanne Chauvel Carlsson, op. cit., p. 136. |

| 28 | See, for example, The Big Picture, op. cit. |

| 29 | ‘Film Man’s Loss’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 5 February 1949, p. 1. |

| 30 | ‘Sons of Matthew’, Ozmovies, op. cit. |

| 31 | Ric Chauvel Carlsson, op. cit. |

| 32 | Stuart Cunningham, In the Vernacular: A Generation of Australian Culture and Controversy, University of Queensland Press, Brisbane, 2008, p. 65. |

| 33 | Umbrella Entertainment, ‘Sons of Matthew’, <https://www.umbrellaent.com.au/on-demand/3483-sons-of-matthew-on-demand.html>, accessed 11 November 2019. |

| 34 | A February 2019 report by the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) Australia entitled In Their Own Words found that children in rural areas are not receiving the required support amid long-term drought conditions; see Patrick Wood, ‘UNICEF Combines Drought Stories of Country Kids to Warn of Worsening Rural Stress’, ABC News, 19 February 2019, <https://www.abc.net.au/news/2019-02-19/drought-kids-in-crisis-rural-issues-unicef/10820748>, accessed 12 November, 2019. |

| 35 | Pate, in The Big Picture, op. cit. |

| 36 | Paul Byrnes, ‘Charles Chauvel’, Australian Screen, <https://aso.gov.au/people/Charles_Chauvel/portrait/>, accessed 11 November 2019. |

| 37 | Cunningham, Featuring Australia, op. cit., p. 150. |

| 38 | See, for example, Umbrella Entertainment, op. cit. |

| 39 | Matthew 7:25 (King James Version), available at BibleHub, <https://biblehub.com/matthew/7-25.htm>, accessed 11 November 2019. |

| 40 | Tom O’Regan, Australian National Cinema, Routledge, London & New York, 1996, p. 275. |

| 41 | See Michael Klapdor, Moira Coombs & Catherine Bohm, ‘Australian Citizenship: A Chronology of Major Developments in Policy and Law’, Parliament of Australia, <https://www.aph.gov.au/About_Parliament/Parliamentary_Departments/Parliamentary_Library/pubs/BN/0910/AustCitizenship>, accessed 11 November 2019. |

| 42 | Chelsea Barnett, Reel Men: Australian Masculinity in the Movies 1949–1962, Melbourne University Publishing, Melbourne, 2019, pp. 42–3. |

| 43 | See Michael Slezak, ‘“Global Deforestation Hotspot”: 3m Hectares of Australian Forest to Be Lost in 15 Years’, The Guardian, 5 March 2018, <https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2018/mar/05/global-deforestation-hotspot-3m-hectares-of-australian-forest-to-be-lost-in-15-years>, accessed 11 November 2019. |

| 44 | Sophie Cunningham, City of Trees: Essays on Life, Death and the Need for a Forest, Text Publishing, Melbourne, 2019, p. 7. |

| 45 | Sophie Cunningham, quoted in Katinka Smit, ‘Notes from the Festival: Sophie Cunningham’, Northerly, Spring 2019, p. 15. |

| 46 | O’Regan, op. cit., p. 274. |

| 47 | Christos Tsiolkas, On Patrick White, Black Inc., Melbourne, 2018, p. 34. |

| 48 | ‘What Killed Our Film Industry?’, The Sunday Mail, 17 February 1952, p. 11. |

| 49 | F Keith Manzie, ‘Pioneer Spirit Inspired Australian Film’, The Argus, 19 May 1950, p. 9. |

| 50 | Susanne Chauvel Carlsson, op. cit., p. 136. |

| 51 | ‘Australian Film Fails in U.S.’, The Mercury, 16 January 1950, p. 4. |

| 52 | Bosley Crowther, ‘The Screen in Review; Dream No More, Story About Israel in Documentary-type Picture, of Ambassador at the Park Avenue at the Palace’, The New York Times, 6 January 1950, p. 25, available at <https://www.nytimes.com/1950/01/06/archives/the-screen-in-review-dream-no-more-story-about-israel-in.html>, accessed 11 November 2019. |

| 53 | All cited in ‘What London Says of Matthew’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 28 January 1950, p. 3. |

| 54 | ‘Gossip from the Studios’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 30 November 1950, p. 17. |

| 55 | ‘Australian Film “for Posterity”’, The Advertiser, 7 October 1950, p. 15. |

| 56 | Josephine O’Neill, ‘Sons of Matthew’, The Daily Telegraph, 18 December 1949, p. 51. |

| 57 | MJ McMahon, ‘Talking of Films’, The Australian Women’s Weekly, 31 December 1949, p. 32. |

| 58 | Lindsey Browne, ‘Reviews of New Films’, The Sunday Herald, 18 December 1949, p. 36. |

| 59 | Andrew Katsis, ‘“You and the Earth, Cathy. That’s All I Want.” Sons of Matthew (Charles Chauvel, 1949)’, Senses of Cinema, issue 58, March 2011, <http://sensesofcinema.com/2011/key-moments-in-australian-cinema-issue-70-march-2014/you-and-the-earth-cathy-thats-all-i-want-sons-of-matthew-charles-chauvel-1949/>, accessed 11 November 2019. |

| 60 | Umbrella Entertainment, op. cit. |

| 61 | Ric Chauvel Carlsson, op. cit. |