The announcement that a prestige biopic on Australian-born musician Helen Reddy was to be Screen Australia’s jewel in the world-premiere crown at the 2019 Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF) was met – in my anecdotal experience, by almost everyone I know under forty – with an immediate and emphatic, ‘Who?’ For some, a few bars of ‘I Am Woman’, Reddy’s 1972 blockbuster single that became synonymous with the second-wave-feminist movement, might have rung a bell, but only maybe. Even I (and I’m over forty) had only the smallest fragments of recollection to work with. Somewhere in the memory banks was a faded echo of seeing Reddy on reruns of The Muppet Show when I was a kid, singing ‘You and Me Against the World’ with Kermit the Frog. Perhaps more vividly, I remember ‘I Am Woman’ being sung at school in notably sarcastic, accusatory tones if anyone dared espouse explicitly feminist ideas during those icky dark days of late-1980s anti-feminist backlash, whose tentacles even made their way into the suburban Canberran high schools I had the great misfortune of attending.[1]For more on this broader phenomenon, see Susan Faludi, Backlash: The Undeclared War Against American Women, Crown, New York, 1991.

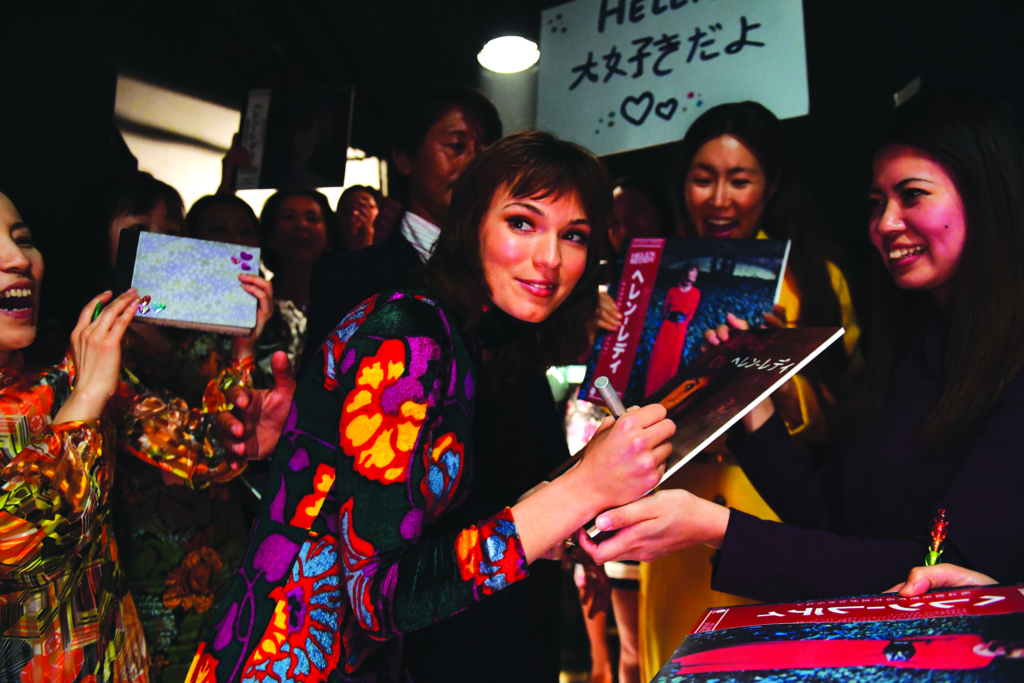

While I am hardly a young woman, at the TIFF screening of Unjoo Moon’s I Am Woman (2019), I became acutely aware of my difference from the dominant audience demographic around me. I was, in that vast cinema, very much a loner with these thoughts. As the excited lines of viewers (almost all women) poured into the theatre, there was a palpable buzz even beyond that which usually marks a high-profile TIFF world premiere; this felt like an army coming to see an old friend. The film hadn’t even started when my reading of the room was verified. As the headphone-wearing, clipboard-wielding front-of-house manager walked us through some of the usual pre-screening admin about sitting arrangements, et cetera, she couldn’t contain her excitement. After briefly but passionately belting out a few lines from the titular song, she announced breathlessly, ‘I remember this song!’ She was clearly not alone, and, before the audience had finished taking their seats, the hooting and hollering had begun. The women who sat with me – who surrounded me – they remembered, too. Those memories were what brought them there.

She is woman

I Am Woman begins as Helen (Tilda Cobham-Hervey) arrives in New York City, having won the opportunity to audition for a record contract with Mercury Records in 1966. Walking out of the subway, she holds the hand of her young daughter, Traci (Scout Bowman) – it’s revealed she’s a single mum – in heavily romanticised slow motion, a technique the film returns to throughout to create a dreamlike quality that contrasts neatly with the often much darker reality of Helen’s ascent to fame. Her audition is a disaster, and sexist clichés fly at her from all directions: Is she on a diet? Where is her husband? Dismissed pretty much immediately, Helen feels her ambitions are crushed on her arrival. Boy bands like The Beatles are in, she is told; they ‘can’t do anything with a female singer’.

While the parameters of a film that runs just under two hours naturally require the truncation of these events … Moon certainly does not underplay the astonishing list of achievements by reddy.

Almost completely alone in the big city, Helen tracks down an old friend, writer Lillian Roxon (Danielle Macdonald), who is dealing with her own issues at the hands of the patriarchy. Despite her dreams of penning the first encyclopedia on rock’n’roll, Lillian is confined to writing about fashion and beauty tips. But, together, the two friends slowly climb to the top: Lillian publishes the groundbreaking Lillian Roxon’s Rock Encyclopedia in 1969, while Helen – with the support of eventual husband and manager Jeff Wald (Evan Peters), whom she meets through Lillian – becomes one of the most successful pop stars of the 1970s.

While the parameters of a film that runs just under two hours naturally require the truncation of these events, with many reduced to a quick montage, they are worth spelling out in full to communicate how big a star and how pioneering a figure Reddy was. Across the decade, she had fifteen singles in Billboard’s Top 40 charts, three of which made it to the number-one slot (including, of course, ‘I Am Woman’). She won the first ever award for Favorite Pop/Rock Female Artist at the inaugural American Music Awards in 1974, and even hosted a prime-time variety program in 1973 called The Helen Reddy Show. Most significantly, ‘I Am Woman’ won the 1973 Grammy for Best Female Pop Vocal Performance, beating out an extraordinary list of fellow nominees including Roberta Flack, Aretha Franklin, Carly Simon and Barbra Streisand.[2]For more on Reddy, see ‘About Helen Reddy’, in TM Publicity, I Am Woman press kit, 2019, p. 9; ‘Biography’, The Official Helen Reddy Website, <http://helenreddy.com/bio/>; Thorsten Kaeding, ‘Curator’s Notes’, ‘I Am Woman (1972)’, Australian Screen, <https://aso.gov.au/titles/music/i-am-woman/notes/>; and Andrew Stephens, ‘Helen Reddy: Still Roaring at 72’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 16 November 2013, <https://www.smh.com.au/entertainment/music/helen-reddy-still-roaring-at-72-20131114-2xhfl.html>, all accessed 4 March 2020.

Moon certainly does not underplay the astonishing list of achievements by Reddy, who was born in Melbourne in 1941 to a showbiz family, and who had been performing as a singer since before she was five. But it largely forms a backdrop to the real heart and soul of the film: the tension between Helen’s growing status as a key figure in second-wave feminism and the fact that, while Jeff has the commercial nous to target the burgeoning ‘women’s-libber’ consumer demographic, his attitudes towards gender are notably chauvinistic. With his cocaine habit spiralling out of control, Jeff ultimately drives the family to bankruptcy, leading Helen to make a major decision about her future. Having all but given up music, she returns to the stage in the film’s euphoric coda to sing her signature feminist anthem at a reproduction-rights rally in Washington in 1989.

Why now?

The experience of watching Moon’s film in that packed Toronto theatre – much, much more than the content of I Am Woman itself, which, to be blunt, is ultimately little more than a milquetoast biopic – has haunted me ever since. Who were those women? What were they there for? What did this movie – Reddy, her story, her song – represent to them? And, most of all, why now?

The answer lies not in 1966, when I Am Woman begins, but in 2016, with the shock defeat of Hillary Clinton in the United States presidential election. Surrounded by these women, I was struck by how deeply this iconic song so synonymous with second-wave feminism connected with them personally, almost viscerally, as they sung, hooted, fist-pumped the air and, in one notable case, stood on their seat and literally howled. I do recognise that, as a critic, I am generally expected to transcend my own, generation-specific perspective when engaging with any film – in this case, that relating to feminism and political coming of age. But I Am Woman made it clear that it was not for me; it was for them. As HuffPost’s Martha TS Laham has noted, ‘I Am Woman’ was one of ‘the milestone moments in every boomer’s life’.[3]Martha TS Laham, ‘The Milestone Moments in Every Boomer’s Life’, HuffPost, 3 July 2015, <https://www.huffpost.com/entry/boomers-milestone-moments_b_7678270>, accessed 4 March 2020.

I Am Woman is certainly a feel-good movie, consolidating second-wave-feminist boomers’ place in history and bringing to life their battles for so many things that younger, contemporary feminists often take for granted.

Of course, I could only speculate about the specifics of these women’s politics. But, as they formed a representative cluster of a certain demographic clearly aligned with the general ideology championed by I Am Woman, Clinton’s journey has increasingly become the lens through which I’ve been able to understand Moon’s film. Like Reddy, Clinton is synonymous with second-wave feminism. As The New Republic’s Clio Chang suggests, Clinton

is a Baby Boomer who came up through the American university system and fought her way – as a lawyer, senator, and secretary of state – to the top of one male-dominated career after another.[4]Clio Chang, ‘What Is the Post-Hillary Feminism?’, The New Republic, 22 November 2016, <https://newrepublic.com/article/138933/post-hillary-feminism>, accessed 4 March 2020.

Vox’s Emily Crockett notes that Clinton’s plight speaks to ‘older feminists, baby boomers in particular’, because ‘[m]any of them can personally identify with the types of sexism she has experienced, and they’ve seen her spend 40 years getting disparaged for her gender and succeeding in spite of it’.[5]Emily Crockett, ‘Why Some Feminists Are Conflicted About Hillary Clinton’s Historic Candidacy’, Vox, 22 August 2016, <https://www.vox.com/2016/8/22/12370784/hillary-clinton-woman-president-feminists-conflicted>, accessed 4 March 2020. And so, when Clinton battled Barack Obama for the Democratic nomination in 2008 and lost, these second-wave-feminist boomers felt, according to New York Magazine’s Amanda Fortini, that ‘the sexism in America, long lying dormant, like some feral, tranquilized animal, yawned and revealed itself’: ‘Even those of us who didn’t usually concern ourselves with gender-centric matters began to realize that when it comes to women, we are not post-anything.’[6]Amanda Fortini, ‘The Feminist Reawakening’, New York Magazine, 11 April 2008, <https://nymag.com/news/features/46011/>, accessed 4 March 2020. For these very same boomer feminists, Clinton’s subsequent loss during the 2016 US presidential election to an openly misogynistic alleged rapist was not just personally devastating, but consolidated the need for a strongly mobilised contemporary feminist movement the likes of which they witnessed during the second wave.[7]See Amy Chozick, ‘Hillary Clinton Ignited a Feminist Movement. By Losing.’, The New York Times, 13 January 2018, <https://www.nytimes.com/2018/01/13/sunday-review/hillary-clinton-feminist-movement.html>, accessed 4 March 2020.

I’d wager that, for the women in that TIFF audience, seeing the relatively controversy-free life of Reddy – poster girl for that exact era – was the salve desperately needed after Donald Trump’s victory. Even for just a couple of hours, they were able to heal through song, through the example of a woman fighting the odds, wrestling the system, dealing with an industry run by sexist pigs (and a dirtbag husband) and – most of all – using her life experiences to inspire others to fight for a better future for themselves and their daughters.

Safety first!

While watching the thoroughly serviceable Cobham-Hervey re-enact Reddy’s famous performance during I Am Woman’s climactic coda didn’t exactly send me into a feverish frenzy of revolutionary feminism, I have never before – without hyperbole – quite witnessed what I did in Toronto that day. This bears repeating. Although they were strangers, the women in that cinema were joined by a bond that I am sure I will never wholly understand, even though I could recognise it as something powerful that straddled the personal and the political. What they had just seen on screen was their story. How many of them were single mums during this period, or had shitty husbands or misogynistic, horrible bosses? How many of them marched in the very protests and rallies around the world where ‘I Am Woman’ played like the goddamned national anthem? When Helen suffered, these women remembered suffering. When Helen was victorious, they remembered victory. If their responses were anything to go by, this was a fully embodied experience; they felt this film.

I Am Woman is certainly a feel-good movie, consolidating second-wave-feminist boomers’ place in history and bringing to life their battles for so many things that younger, contemporary feminists often take for granted. There is, to state the obvious, nothing wrong with this – and, if that were the film’s goal, then it has achieved it spectacularly. For Moon herself, Reddy represents a pivotal moment in history: ‘[A]s a young child I have vivid memories of the way my mother and her friends used to talk about Helen,’ she writes in her director’s note.

The 1970’s were a time of change – for everything – fashion, music, food, politics, relationships and most importantly, the roles of women were being questioned and challenged […]I knew that somehow Helen Reddy seemed to be an important part of this change […] What started as a beautiful, touching biopic about the queen of ‘housewife rock’ and the music that captured the spirit of an era, has now become even more poignant and deeply relevant to a whole new generation of people.[8]Unjoo Moon, ‘Director’s Statement’, in TM Publicity, op. cit, pp. 3–4.

That Moon mentions a ‘whole new generation’ is worth pausing on; surely I am not the only non-boomer to see this film. The narrative tightness enabled by narrowing the entire plight of the second-wave-feminist movement down to one woman’s relatively sanitised, scandal-free story brings with it the added bonus of being able to sweep under the carpet the more volatile aspects of the movement at the time, not to mention the less positive aspects of it that are still extremely controversial. To spell it out, why Reddy and not, say, Germaine Greer?

Even leaving aside the fact that Greer never did a televised duet with Kermit the Frog, the answer is clear. Greer’s story, from the vantage point of contemporary feminism, is simply too ugly, too hateful, and brings to the surface how thoroughly out of whack the attitudes held by some (although absolutely not all) key second-wave figures are with those of the present moment.[9]For a broader examination of the relationship between trans identities and second-wave feminism, see Talia Bettcher, ‘Feminist Perspectives on Trans Issues’, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, updated 8 January 2014, <https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2014/entries/feminism-trans/>, accessed 4 March 2020. Unlike Reddy, who so gracefully receded from the spotlight, Greer is as well known today for her vitriolic transphobia as for her groundbreaking work advocating for women’s rights.[10]See, for example, Tara John, ‘Germaine Greer Defends Her Controversial Views on Transgender Women’, Time, 12 April 2016, <https://time.com/4290409/germaine-greer-transgender-women/>, accessed 4 March 2020. Outside of a few coy jokes about unisex toilets and a reference to same-sex marriage, I Am Woman steers well clear of anything that might have struck the conservative powers-that-be behind this project or its prospective liberal audience as ‘problematic’, opting consciously for a figure who remains a safe distance from the box-office-ruining terrain of ‘cancel culture’.[11]For more on ‘cancel culture’, see Shamira Ibrahim, ‘In Defense of Cancel Culture’, VICE, 5 April 2019, <https://www.vice.com/en_us/article/vbw9pa/what-is-cancel-culture-twitter-extremely-online>, accessed 4 March 2020.

Watching footage of Reddy’s original 1989 performance on YouTube[12]The original performance can be found on ‘Helen Reddy – I Am Woman – Mobilize for Women’s Lives Rally 1989 – Abortion Rights Rally’, YouTube, 9 October 2017, <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jBZ4As2Si-0>, accessed 4 March 2020., I did find that, even with my disconnection from the milieu that I Am Woman seeks to celebrate, I was struck by the real-life singer’s emotion and gravitas. And while, for me, Moon’s take on the biopic form was pedestrian and colour-by-numbers, those women back in Toronto clearly felt euphoria from being reminded of that moment in history. I may have been one of the few people in that theatre not crying. But the time-capsule quality of Reddy’s performance, not to mention its biopic re-enactment, is itself significant: the world was so much simpler back then (or so we are told), with our feminist fight able to be boiled down to asking one half of the population to listen to the other half ‘roar’. Today, though, it’s not enough to be simply feminist; as some of Clinton’s own critics have pointed out, we are fighting for more than just the ‘glass ceiling’ nowadays, and it’s important that feminist action target inequality across axes of gender, race, class, sexuality and disability.[13]See Crockett, op. cit.

All in all, I Am Woman is pleasantly marketable and eminently fundable – a crowd-pleaser (at least, if you are the ‘crowd’ the film has in mind). But do these qualities make it interesting? Meaningful? Inspiring? Relevant? If you had the luxury of being born between 1946 and 1964, the answer is a resounding ‘yes’.

Endnotes

| 1 | For more on this broader phenomenon, see Susan Faludi, Backlash: The Undeclared War Against American Women, Crown, New York, 1991. |

|---|---|

| 2 | For more on Reddy, see ‘About Helen Reddy’, in TM Publicity, I Am Woman press kit, 2019, p. 9; ‘Biography’, The Official Helen Reddy Website, <http://helenreddy.com/bio/>; Thorsten Kaeding, ‘Curator’s Notes’, ‘I Am Woman (1972)’, Australian Screen, <https://aso.gov.au/titles/music/i-am-woman/notes/>; and Andrew Stephens, ‘Helen Reddy: Still Roaring at 72’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 16 November 2013, <https://www.smh.com.au/entertainment/music/helen-reddy-still-roaring-at-72-20131114-2xhfl.html>, all accessed 4 March 2020. |

| 3 | Martha TS Laham, ‘The Milestone Moments in Every Boomer’s Life’, HuffPost, 3 July 2015, <https://www.huffpost.com/entry/boomers-milestone-moments_b_7678270>, accessed 4 March 2020. |

| 4 | Clio Chang, ‘What Is the Post-Hillary Feminism?’, The New Republic, 22 November 2016, <https://newrepublic.com/article/138933/post-hillary-feminism>, accessed 4 March 2020. |

| 5 | Emily Crockett, ‘Why Some Feminists Are Conflicted About Hillary Clinton’s Historic Candidacy’, Vox, 22 August 2016, <https://www.vox.com/2016/8/22/12370784/hillary-clinton-woman-president-feminists-conflicted>, accessed 4 March 2020. |

| 6 | Amanda Fortini, ‘The Feminist Reawakening’, New York Magazine, 11 April 2008, <https://nymag.com/news/features/46011/>, accessed 4 March 2020. |

| 7 | See Amy Chozick, ‘Hillary Clinton Ignited a Feminist Movement. By Losing.’, The New York Times, 13 January 2018, <https://www.nytimes.com/2018/01/13/sunday-review/hillary-clinton-feminist-movement.html>, accessed 4 March 2020. |

| 8 | Unjoo Moon, ‘Director’s Statement’, in TM Publicity, op. cit, pp. 3–4. |

| 9 | For a broader examination of the relationship between trans identities and second-wave feminism, see Talia Bettcher, ‘Feminist Perspectives on Trans Issues’, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, updated 8 January 2014, <https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2014/entries/feminism-trans/>, accessed 4 March 2020. |

| 10 | See, for example, Tara John, ‘Germaine Greer Defends Her Controversial Views on Transgender Women’, Time, 12 April 2016, <https://time.com/4290409/germaine-greer-transgender-women/>, accessed 4 March 2020. |

| 11 | For more on ‘cancel culture’, see Shamira Ibrahim, ‘In Defense of Cancel Culture’, VICE, 5 April 2019, <https://www.vice.com/en_us/article/vbw9pa/what-is-cancel-culture-twitter-extremely-online>, accessed 4 March 2020. |

| 12 | The original performance can be found on ‘Helen Reddy – I Am Woman – Mobilize for Women’s Lives Rally 1989 – Abortion Rights Rally’, YouTube, 9 October 2017, <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jBZ4As2Si-0>, accessed 4 March 2020. |

| 13 | See Crockett, op. cit. |