THE NFSA RESTORES COLLECTION: PART 53

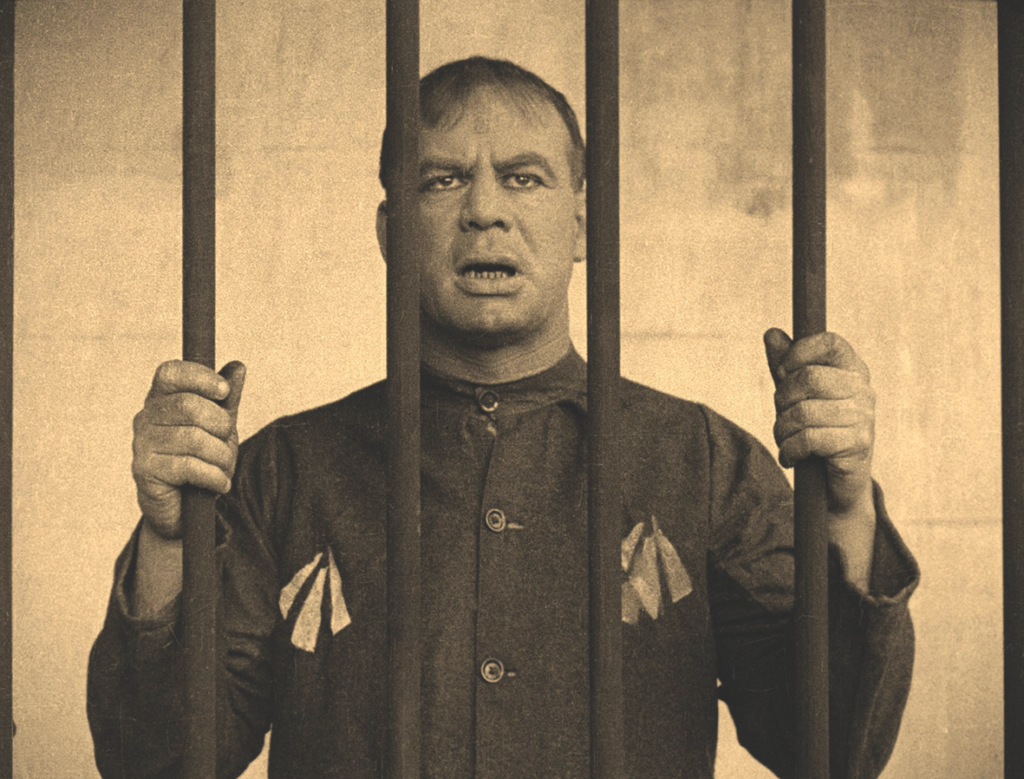

‘Film is a fragile medium,’ writes Harrison Bryan, former director-general of the National Library of Australia, to open his preface for Ray Edmondson and Andrew Pike’s 1982 book Australia’s Lost Films: The Loss and Rescue of Australia’s Silent Cinema. This might seem a distant, strange statement in the robust digital age, when information and data are created, presented, viewed and stored so efficiently and thoughtlessly – but it was once so. Bryan is referring to the ‘inexorable laws of chemistry’[1]Harrison Bryan, ‘Preface’, in Ray Edmondson & Andrew Pike, Australia’s Lost Films: The Loss and Rescue of Australia’s Silent Cinema, National Library of Australia, Canberra, 1982, p. 5. as they apply to the delicateness, vulnerability and limited shelf life of cellulose nitrate film, of which most theatrical films were made until 1951,[2]See Monique Fischer, ‘A Short Guide to Film Base Photographic Materials: Identification, Care, and Duplication’, Northeast Document Conservation Center website, 2020, <https://www.nedcc.org/free-resources/preservation-leaflets/5.-photographs/5.1-a-short-guide-to-film-base-photographic-materials-identification,-care,-and-duplication>, accessed 20 April 2021. after which time cellulose acetate and eventually polyester took over.[3]See ‘History of Film Types Timeline’, National Park Service website, updated 18 December 2019, <https://www.nps.gov/subjects/hfc/history-of-film-types-timeline.htm>, accessed 20 April 2021. This long out-of-print, largely unheralded but important book features on its cover a photo of the silent film actor Arthur Tauchert,[4]The photo is a still from the film Joe (Beaumont Smith, 1924). See Edmondson & Pike, op. cit., p. 2. one of the two leads in Raymond Longford’s iconic feature The Sentimental Bloke (1919). Edmondson and Pike detail and mourn the fact that many Australian films did not survive the silent era because of these inexorable laws – but the nitrate-based The Sentimental Bloke is, of course, thankfully not among them.

Given that fragility, it is something of a wonder that we have Longford’s film to enjoy today. And this artefact is remarkable in many other ways aside from the sheer fact of its existence. The film’s technical innovation remains impressive even more than 100 years after its release, and is particularly apparent now thanks to the restoration efforts of the National Film and Sound Archive (NFSA); the acting performances from Tauchert and Lottie Lyell are as passionate as they are witty and wry; and Longford’s unique visual language is innovative and poetic, and offers fascinating and historic film of Sydney from around the time of the end of World War I. Then there is the characterisation, plot, and distinctive and earthy language, all of which come courtesy of the CJ Dennis verse novel upon which the film is based, The Songs of a Sentimental Bloke.

Such elements as these all stem from the original production of the film in 1918 and its key contributors, most notably Longford, Lyell, Tauchert and Dennis. However, in the context of the NFSA Restores series, this is one film for which the restoration and re-presentation process has been much more than just a technical brush-up. The new version of The Sentimental Bloke offers renewed narrative thrust, an altered emotional trajectory and an overall tone and feel that is a pleasing mixture of the silent era and the present day. And this is down to the film’s new score by the Australian musician Paul Mac. Because of Mac’s composition – which constitutes over an hour and forty-five minutes of continuous music and is, by any standards, a remarkable creative effort as well a transformative influence on the original film – The Sentimental Bloke has been not only restored, but also reimagined and reinterpreted. Longford’s silent picture is now a filmic experience that the director could not possibly have imagined.

To consider The Sentimental Bloke in 2021 is also, as alluded to, to respond to the language of Dennis’ poetry, which makes up the film’s intertitles. In the restored version, these intertitles are recited by the contemporary actor Rhys Muldoon – another key modern element, along with Mac’s score, that gives the film new energy and a reinvigorated theatricality. Dennis’ language is absorbing in its melodic and rhythmic harnessing of the working-class vernacular of the period, yet it also presents certain words and labels that jar with contemporary sensibilities and sensitivities, even if these don’t really interfere with the film’s charm. The Sentimental Bloke has also attracted critical analysis in terms of its handling of class and gender, and can be looked at as an important sociocultural document in these terms.

A great silence

The absence today of many Australian films from the silent era[5]The silent-film era can be regarded as spanning 1894 to 1929. See Donna Kornhaber, ‘Silent Film’, Oxford Bibliographies, 2020, <https://www.oxfordbibliographies.com/view/document/obo-9780199791286/obo-9780199791286-0223.xml>, accessed 21 April 2021. represents a well-known and most likely permanent hole in the nation’s cinematic heritage. The exact number of silent films that are lost or missing appears to be unclear; however, the NFSA has stated that ninety per cent of Australian films made before 1930 are gone,[6]See ‘NFSA’s Most Wanted’, National Film and Sound Archive of Australia website, 13 September 2016, <https://www.nfsa.gov.au/nfsa-most-wanted>, accessed 21 April 2021. while Edmondson and Pike estimate that of the 250 Australian films made between 1906 and 1930, only fifty survive.[7]Edmondson & Pike, op. cit., p. 9.

There are several reasons for this, and Joan and Martin Long in The Pictures That Moved offer a neat summary of them:

Nitrate film, the stock on which all 35 mm films were made up to 1951, is doomed to a process of chemical decomposition, more or less gradual, depending on the conditions under which the film has been kept. But the main reason for the films’ disappearance is simply that they were thrown away: burnt on tips, dumped at sea, melted down at paint and boot polish factories, despised by the generation immediately following as worn-out, out-of-date old movies.[8]Joan Long & Martin Long, The Pictures That Moved: A Picture History of the Australian Cinema 1896–1929, Hutchinson, Richmond, Vic., 1982, p. 11.

Nitrate film is also highly flammable. ‘Nitrate is a very volatile medium,’ says Elena Guest, NFSA Restores program manager, ‘and if it catches fire, end of story for everything, really. We have specific nitrate vaults in Canberra that we store nitrate film in.’[9]Elena Guest, in ‘The Sentimental Bloke’, Living History with Mat McLachlan, 5 February 2020, <https://podcasts.apple.com/at/podcast/living-history-with-mat-mclachlan/id1317242813>, accessed 21 April 2021. Lost silent films are certainly not unique to Australia, it should be noted: American silent films were subject to the same destructive forces, and only a fraction of them survive too.[10]See ‘“Lost” Silent Films to be Restored’, ABC News, 24 April 2008, <https://www.abc.net.au/news/2008-04-24/lost-silent-films-to-be-restored/2414434>, accessed 21 April 2021.

The film had been thought lost until 1952, when a tinted nitrate 35mm print was discovered in the vaults of the government’s Department of Information in Melbourne.

It is an extraordinarily fortunate thing, then, that The Sentimental Bloke is available to us now. The film had been thought lost until 1952,[11]Graham Shirley, ‘How the NFSA Restored and Re-released The Bloke’, National Film and Sound Archive of Australia website, 5 August 2011, <https://www.nfsa.gov.au/latest/sentimental-bloke>, accessed 21 April 2021. when a tinted nitrate 35mm print was discovered in the vaults of the government’s Department of Information (previously known as the Cinema Branch[12]See ‘100 Years of Film Australia’, National Film and Sound Archive of Australia website, 15 April 2013, <https://www.nfsa.gov.au/latest/film-australia-chronology>, accessed 22 April 2021.) in Melbourne.[13]See Long & Long, op. cit., p. 64. According to the film historian Graham Shirley, the print had even survived ‘a couple of nitrate film vault fires’.[14]Shirley, op. cit. The guardian angels of cinema seemed to be watching over Longford’s film.

This newly found nitrate print was sent to Automatic Film Laboratories in Sydney for the nitrate to be respliced and the film copied by one fifteen-year-old Tony Buckley, who went on to become one of Australia’s most famous film producers and editors. It was eventually screened to significant acclaim at the 1955 Sydney Film Festival.[15]ibid.

The story of The Sentimental Bloke’s re-emergence took another pivotal turn in 1973 when Edmondson located another copy of the film at the George Eastman Museum in Rochester, New York, one of the world’s leading archives of film and photography. This print was wrongly labelled ‘The Sentimental Blonde’, and featured different intertitles adapted for a possible US release in the 1920s, catering to audiences who would no doubt have been bamboozled by Dennis’ Australian slang. This print was shorter in duration than the version found in Melbourne, but it also contained scenes that were missing from that 1952 find.[16]ibid.

Using all the materials available from both discoveries, the NFSA embarked on a major restoration of the film in 2000, culminating in a triumphant showing at the Sydney Film Festival in 2004. A DVD box set was released in 2009.[17]ibid. The latest restoration, with Mac’s and Muldoon’s contributions its key highlights, marked the 100th anniversary of the film’s release, and premiered in February 2020 at Sydney’s Westpac OpenAir Cinema, with Mac giving a live performance of his score.[18]‘Paul Mac Creates New Music for 100-year-old Film The Sentimental Bloke’, media release, National Film and Sound Archive of Australia, 14 January 2020, <https://www.nfsa.gov.au/paul-mac-creates-new-music-100-year-old-film-sentimental-bloke>, accessed 22 April 2021.

Birth of a larrikin

Dennis’ The Songs of a Sentimental Bloke was first published by Angus & Robertson in 1915, with illustrations by Hal Gye. The volume, usually described as a verse novel, was identified by critic Nathanael O’Reilly in a review of the 2012 Text Classics edition as ‘arguably […] the most popular book of poetry ever published in Australia’.[19]Nathanael O’Reilly, ‘Nathanael O’Reilly Reviews The Songs of a Sentimental Bloke and Searching for The Man from Snowy River’, Cordite Poetry Review, 1 September 2013, <http://cordite.org.au/reviews/oreilly-dennis-refshauge/>, accessed 22 April 2021. And that’s fair: sales surpassed 100,000 in the five years following publication alone.[20]‘The Songs of a Sentimental Bloke’, AustLit, updated 29 November 2019, <https://www.austlit.edu.au/austlit/page/C204825>, accessed 22 April 2021. The book was particularly popular during World War I, with publishers releasing a ‘pocket edition for the trenches’ for servicemen based overseas.[21]ibid. The poetry’s language and story, which is set in Melbourne and follows the efforts of larrikin and roustabout Bill as he falls for and tries to court his love interest Doreen, struck a special chord with the Australian public that few literary works have ever achieved.[22]Not everyone was impressed: artist Norman Lindsay loathed The Songs of a Sentimental Bloke so much that he ‘crucified’ a copy on a homemade cross in his front garden. See Philip Butterss, An Unsentimental Bloke: The Life and Work of C.J. Dennis, Wakefield Press, Adelaide, 2014, p. 79.

The genesis of Dennis’ phenomenally successful book can be traced back to 1909, when the first two poems in the series appeared in The Bulletin. Eight more appeared in the same publication across 1914 and 1915, by which time Dennis had made moves to publish the series as a book. After a couple of rejections, he eventually secured the deal with Angus & Robertson. His friend Henry Lawson wrote the preface, and this first edition also included a glossary for the many slang terms that defined Dennis’ poetry.[23]‘The Songs of a Sentimental Bloke’, op. cit. Dennis biographer Philip Butterss describes the premise of The Songs of a Sentimental Bloke as ‘a larrikin expressing his love for his sweetheart in the idiom of the streets’.[24]Butterss, op. cit., p. 37.

The idea for The Songs of a Sentimental Bloke came from an encounter Dennis had with a visitor to Toolangi, Victoria, where he lived for much of his life. This young man, a plumber from the rough-and-tumble backstreets of Melbourne, was in town to enjoy his hobby of horse training. Butterss’ account of how this lovesick man inspired Dennis offers a neat summary of the spirit and thematic intention behind both the book and Longford’s film:

Always interested in language, Dennis had listened to the lad’s speech and was struck by the incongruity between inner-city slang and deep emotion after the young man fell in love with a local settler’s daughter. When he heard rumours that the plumber had behaved inappropriately with the young woman, Dennis confronted him and received an almost tearful denial: ‘Gor blime, Mr. Dennis … I’ve got sisters of me own!’ This combination of love and what were called ‘finer feelings’ is what Dennis had in mind when he first used the epithet ‘sentimental’ for his creation, the Bloke.[25]ibid.

Longford adopts the larrikin

Dennis himself had made attempts at writing a screenplay based on The Songs of a Sentimental Bloke, a project embarked upon in 1915 prior to the book’s publication. However, he never made meaningful progress due to a lack of the requisite skill for this particular kind of writing.[26]ibid., pp. 73–4. Dennis didn’t have to wait long, though, for the established filmmaking team of Longford and Lyell to be drawn to his book.

Longford, born in Melbourne in 1878, entered show business in the 1900s after having been a sailor in his younger years, serving in the Boer War.[27]Long & Long, op. cit., p. 36. At first, he worked as an actor, his most notable role coming in Captain Midnight, the Bush King (Alfred Rolfe, 1911). Perhaps holding him in good stead for The Sentimental Bloke, two of his earliest films as a director were adaptations of plays: The Fatal Wedding (1911) and The Midnight Wedding (1912).[28]Eric Reade, Australian Silent Films: A Pictorial History of Silent Films from 1896 to 1929, Lansdowne Press, Melbourne, 1970, p. 180. His most important work prior to The Sentimental Bloke was arguably Sweet Nell of Old Drury (1911), now lost, about the relationship between King Charles II and Nell Gwynne.[29]Eric Reade writes of Sweet Nell of Old Drury, ‘No doubt Raymond Longford found this one of his most rewarding films as a director.’ Ibid., p. 62.

Lyell was born in Sydney in 1890. She embarked on an acting career on stage in 1907,[30]Andrée Wright, Brilliant Careers: Women in Australian Cinema, Pan Books, Sydney, 1986, p. 2. her film debut coming alongside Longford in Captain Midnight. In what may come as a surprise to anyone who has only seen Lyell as a demure and composed presence in The Sentimental Bloke, in the years prior to that film she had made a name for herself as an all-action performer with an impressively diverse range of skills. She was, as film historian Andrée Wright puts it, a ‘spirited girl of the bush’[31]ibid. and ‘the Australian girl who could ride a horse, throw a steer or bake a cake’.[32]ibid., p. 5. Films that cemented this reputation included The Tide of Death (Longford, 1912) and ’Neath Austral Skies (Longford, 1913). Demonstrating her depth as a performer, she also appeared in the emotional melodrama The Woman Suffers (Longford, 1918) as a young pregnant woman who is abandoned.

The relationship between Longford and Lyell began after Lyell’s parents placed their teenage daughter in Longford’s care when they were both actors in a play that toured New Zealand. Longford, who was a friend of Lyell’s parents, was married at the time.[33]Margot Nash, ‘Lottie Lyell’, Women Film Pioneers Project, 2018, <https://wfpp.columbia.edu/pioneer/lottie-lyell/>, accessed 23 April 2021. Drawn to one another both artistically and personally, Longford and Lyell went on to form an immensely productive filmmaking partnership, yielding no fewer than twenty-five films, eighteen of which featured Lyell in a starring role.[34]Shirley, op. cit. Wright offers different numbers, writing, ‘Lottie Lyell worked on at least twenty-eight films with her partner Raymond Longford, and acted in twenty-one of them.’ Wright, op. cit., p. 2. As for their romantic coupling, Wright writes that Lyell’s ‘personal relationship with Longford endured for seventeen years although a formal marriage was never possible’.[35]Wright, op. cit., p. 10.

For the most part, official credits for Lyell’s non-acting contributions to her and Longford’s films do not do her justice.

For the most part, official credits for Lyell’s non-acting contributions to their films do not do her justice.[36]Margot Nash, ‘Lottie Lyell: The Silent Work of an Early Australian Scenario Writer’, Screening the Past, no. 40, September 2015, <http://www.screeningthepast.com/issue-40-first-release/lottie-lyell-the-silent-work-of-an-early-australian-scenario-writer/>, accessed 24 April 2021. Joan and Martin Long state that, throughout their partnership, Lyell ‘assisted [Longford] as scriptwriter, designer, editor and associate director’.[37]Long & Long, op. cit., p. 36. However, the word ‘assist’ might well underestimate her contributions.[38]The Longford Lyell Award, the highest honour that the Australian Academy of Cinema and Television Arts can bestow on an individual, changed its name from the Raymond Longford Award in 2015 ‘in recognition of Raymond Longford’s partner in filmmaking and in life, Lottie Lyell’. See ‘Longford Lyell Award’, Australian Academy of Cinema and Television Arts website, <https://www.aacta.org/aacta-awards/longford-lyell-award/>, accessed 24 April 2021. In regard to The Sentimental Bloke, in which Lyell plays the role of Doreen, the filmmaker and writer Margot Nash also credits Lyell with screenplay, art direction, editing and production assistance.[39]Nash, ‘Lottie Lyell’, op. cit. Some commentary suggests it conceivable that she assisted Longford with direction, too.[40]See Bronwyn Coupe, Jennifer Coombes & Tenille Hands, ‘Women Leaders in Film: Lottie Lyell, the McDonagh Sisters and Rachel Perkins’, National Film and Sound Archive of Australia website, 28 February 2014, <https://www.nfsa.gov.au/latest/women-film-lottie-lyell>, accessed 24 April 2021.

In 1915, Longford and Lyell spent time in New Zealand shooting both A Maori Maid’s Love (1916) and Mutiny of the Bounty (1916). Upon returning to Australia, Longford was ‘caught up in Bloke fever’, as Butterss puts it. He was urged to read The Songs of a Sentimental Bloke by the film producer JD Williams, and both Longford and Lyell were enchanted.[41]Butterss, op. cit., p. 137. Lyell, Longford stated, was ‘positively certain it would prove a great success’.[42]Raymond Longford, quoted in Wright, op. cit., p. 6. Nevertheless, Wright notes that the pair were met with derision by several of the writers and financiers they consulted about the idea.[43]Wright, ibid., p. 6. However, Butterss writes of Longford also consulting David McKee Wright and William Macleod of The Bulletin, among others, and implies there was no discouragement from these crucial figures in the publishing history of The Songs of a Sentimental Bloke.[44]Butterss, op. cit., p. 137.

Longford and Lyell did not get around to thinking about filming The Sentimental Bloke until after shooting had wrapped on The Woman Suffers in 1917. That film was made for the South Australia–based company Southern Cross Feature Films. Longford approached the same company with the idea of adapting Dennis’ verse novel, and Southern Cross promptly went to Dennis to gauge his feelings about it. The poet was initially unimpressed at the prospect, concerned about how his beloved characters might be portrayed and that a film might detract from book sales.[45]ibid.

Dennis was also initially unconvinced by the credentials of both Longford and Southern Cross in terms of their stature in the film industry. He did, of course, eventually come round – undoubtedly, in part, because he received as his fee half of the film’s A£2000 budget. Butterss points out how extraordinary this figure was: Henry Lawson received A£200 for the picture rights for his combined works, and ‘Banjo’ Paterson received just A£125 for the rights to The Man from Snowy River along with the rest of his books with Angus & Robertson.[46]ibid., pp. 137–8. Dennis’ reservations about Longford’s abilities were eased after he viewed The Woman Suffers, with the poet writing to publisher George Robertson, ‘I am pleased to say that the filming of the Bloke seems to be in the right hands. It will not only be a financial but also an artistic success.’[47]CJ Dennis, quoted in Butterss, op. cit., p. 139.

Shooting the Bloke

Southern Cross did accept Longford’s proposal, and the company confirmed backing of the film in early 1918.[48]See Andrew Pike & Ross Cooper, Australian Film, 1900–1977: A Guide to Feature Film Production, Oxford University Press & Australian Film Institute, Melbourne, 1980, p. 119. Before production could begin, however, one crucial piece of casting was required: the Bloke, Bill, himself.

Tauchert had led a life prior to acting that would prepare him perfectly for the role. Born in 1877, he grew up in Sydney’s grim and poverty-stricken inner suburbs, and bounced between labouring jobs as a young adult until, thanks to his theatrical proclivities, he found himself on the vaudeville circuit. His profile in vaudeville grew during the 1900s and 1910s, when he worked across Australia and New Zealand. It was through performing in this capacity that Longford discovered him – at a time when Tauchert had only one film performance to his name, in Charlie at the Sydney Show (John Gavin, 1916).[49]ibid., p. 122. Of Longford’s (vindicated) artistic reasons for casting Tauchert, Butterss writes:

Longford had spent considerable time hunting for someone who could depict both blokedom and sentimentality, and Tauchert’s physique was balanced by his facial expressions, which retained an innocence and were able to reveal the depth of his love for Doreen; the shot of him weeping with remorse after his night on the town is a memorable image of deep feeling in a stereotypical male body.[50]Butterss, op. cit., p. 150.

Longford once described Tauchert as ‘the most lovable larrikin that ever lived’.[51]Raymond Longford, quoted in Pike & Cooper, op. cit., p. 122. The other significant casting decision in The Sentimental Bloke was Gilbert Emery as Ginger Mick, Bill’s friend who leads him astray by enticing him with drinking and gambling. Emery had previously worked with Longford and Lyell on a 1910 stage production of The Fatal Wedding.[52]‘The Fatal Wedding: A Crowded House’, Northern Star, 26 August 1910, p. 2.

Production on the film had begun by the middle of 1918, and a print was ready for a private screening in Adelaide by November – an astonishingly fast turnaround by modern standards. Despite this apparent efficiency, Longford and Lyell did face a number of obstacles during shooting, chief among them being authorisation – or lack thereof – to film in certain locations.[53]Pike & Cooper, op. cit., p. 120.

While Longford was able to shoot scenes in most of his desired locations, the production was frustrated by uncooperative city bureaucrats who made logistical life singularly difficult for the director and his team. Local government was reportedly completely uninterested in Longford and Lyell’s efforts to make The Sentimental Bloke. As Pike and fellow film historian Ross Cooper write, the pair were forced to ‘resort to subterfuge to work their way around official obstruction’. On occasion, it wasn’t even subterfuge: upon being refused permission to film a scene on a bench in Sydney’s Royal Botanic Gardens, Longford went ahead and openly did it anyway.[54]ibid.

A scene depicting a police raid on a two-up game was also complicated, in that Longford was not allowed to use police uniforms in the film. A deal was eventually struck with Commonwealth dockside officials, who played the parts of policemen. Longford was also refused permission to film inside any Sydney jails (Bill is incarcerated early in the film). An old watch house in Woolloomooloo ended up filling in.[55]ibid.

Another awkward moment in shooting came when Tauchert got overexcited in a scene in which he scuffles with a policeman – presumably, one of those dockside officials. ‘Tauchert and his adversary evidently got carried away,’ writes Butterss, ‘and, according to one account, seven spectators were needed to “drag the torn, dirty, and bleeding combatants apart”.’[56]Butterss, op. cit., p. 150.

Part of The Sentimental Bloke’s appeal to modern audiences must surely be its footage of buildings and scenes in central Sydney from over a century ago. Guest has highlighted the ‘footage of Central Station before the clock tower was built’, along with film of trams and the entrance to Darlinghurst Gaol (now the National Art School), as being particularly noteworthy.[57]Guest, op. cit. However, Dennis’ The Songs of a Sentimental Bloke was set in Melbourne, with Longford and Lyell’s transplanting of the action to Sydney – specifically, Woolloomooloo – being arguably the biggest change between source text and film script. A definitive explanation as to why this relocation occurred appears to be unavailable, but we can speculate. Although he was born in Melbourne, Longford grew up in Darlinghurst and Woolloomooloo, and Lyell, who grew up in Balmain, would surely have been familiar with the area too. The most likely explanation may be, simply, that the film’s major creative forces knew inner Sydney so intimately that setting the film there was the natural choice. Likewise, Waterloo-born Tauchert would certainly have had an affinity for Woolloomooloo and surrounds, given his background as a labourer in the area.

A further consideration may have been the fact that, as critic Paul Byrnes writes in relation to The Sentimental Bloke, Woolloomooloo ‘had a well-deserved reputation as a tough, inner-city neighbourhood’, even if the worst of the violence, led by street gangs, had subsided by the time The Sentimental Bloke was made.[58]Paul Byrnes, ‘Curator’s Notes’, in ‘The Sentimental Bloke (1919)’, Australian Screen, <https://aso.gov.au/titles/features/sentimental-bloke/notes/>, accessed 24 April 2021. Nevertheless, these suburbs remained working-class slums in the late 1910s.[59]See ‘The Slums of Sydney’, The Sunday Times, 18 January 1920, p. 3. All up, it was the ideal environment for Bill and his day-to-day struggles and pleasures. And as Joan and Martin Long note, ‘The shift of locale from Dennis’s Melbourne to Sydney seems to have caused no comment or criticism when the film appeared.’[60]Long & Long, op. cit., p. 41.

The film was mostly shot in Woolloomooloo itself. The beach scenes are immediately recognisable as Manly Beach, while interior scenes were filmed on open-air sets at Wonderland City,[61]See Pike & Cooper, op. cit., p. 120. a former amusement park that had once been Bondi Aquarium.[62]See Einar Docker, ‘Where Is Wonderland? – Tamarama’s Secret Past’, Museum of Applied Arts & Sciences, 28 August 2013, <https://maas.museum/inside-the-collection/2013/08/28/where-is-wonderland-tamaramas-secret-past/>, accessed 24 April 2021. The film’s orchard and farm scenes were shot in Hornsby, north of Sydney, with scenes featuring a bandstand filmed at a Henley Beach rotunda[63]Butterss, op. cit., p. 150. in Southern Cross Feature Films’ home city of Adelaide; the images of sunsets and sunrises that accompany the intertitles were also filmed in the South Australian capital.[64]Pike & Cooper, op. cit., p. 120.

The release and distribution of The Sentimental Bloke were far from smooth. Australasian Films, a distribution company that eventually merged with Greater Union in the 1930s, refused to show the film in its theatres – Butterss suggests this may have been down to a commercially motivated preference for American films over Australian ones.[65]Butterss, op. cit., p. 152. However, the film soon reached the eyes of EJ and Dan Carroll, Queensland film entrepreneurs and distributors. EJ Carroll had been a producer on the landmark picture For the Term of His Natural Life (Charles MacMahon, 1908). Identifying The Sentimental Bloke’s potential appeal, the Carrolls took it upon themselves to distribute the film both in Australia and overseas.[66]Pike & Cooper, op. cit., p. 120. The Sentimental Bloke opened to a packed Melbourne Town Hall on 4 October 1919, with the Sydney premiere coming on 18 October at the Theatre Royal, where it ran for a then extraordinary three weeks.[67]ibid. The Carrolls took the film to Britain for trade viewings, but it would not be released to the public there until 1922.[68]Butterss, op. cit., pp. 152–3.

‘Put in the boot!’: Plot

The first scene of The Sentimental Bloke is actually a shot of Dennis. He sits writing at a desk, pausing occasionally to think and smoke a pipe. The inclusion of this very brief scene represents an interesting decision by Longford, and might be seen as admirably selfless. In focusing on Dennis in this way, it is as though Longford is consciously identifying the author as the driving creative force behind the film – even more so than himself as director. It is hard to think of, or imagine, many other directors deferring authorship to the original writer of an adapted work in any similar way.

The film proper opens with The Sentimental Bloke, Bill, leaving his home and calling on Ginger Mick, whom Bill introduces as ‘me cobber’. Together, they head to the pub and commence ‘getting on the shick’, as Muldoon’s spoken intertitles in the NFSA Restores version inform us. They then attend an illegal game of two-up, in which Bill loses. The game is raided by police, and, after a chase and a fight, Bill is apprehended (Ginger Mick evades capture by hiding in hay) and ‘gets a stretch for stoushin’ Johns’: six months.

Upon release, he is directionless and depressed, and vows to mend his ways and get a ‘good, stiddy job’. He becomes a hawker, and while working at a market he sets eyes on Doreen for the first time. Despite his initial attempts to converse being rebuffed, he regards her as his ‘ideel tart’, and tries to engage her again another day, but is once more ignored. Subsequently, he follows her to her place of work, a pickle factory, where it turns out a friend of his also works. Bill persuades this friend (Stanley Robinson) to help him get a meeting with Doreen.

The plan works, and Bill and Doreen meet formally. After initial awkwardness, Bill becomes completely smitten, and the pair arrange to meet again. One of the most comic moments in the film comes as Bill counts the days: his beloved’s face appears to him in a large pumpkin he has sliced open with a knife. When they meet again, Bill and the ‘bonzer peach’, Doreen, take the ferry to the beach, and here they embrace and their romantic entanglement begins. Bill promises to stop drinking and gambling for her sake. He gets a job at a printing factory.

Then comes one of the most memorable and famous sections in The Sentimental Bloke: Bill and Doreen go to the theatre to see Romeo and Juliet. The couple chomp down sweets as they watch the play, with Bill’s lengthy retelling of Shakespeare’s plot in his distinctive ‘Strine’ another of the film’s comedic highlights, culminating in his hilarious bellowing at the stage of ‘Put in the boot!’ when Romeo avenges the death of Mercutio (or ‘Mick Curio’, as Dennis’ verse renames the character) by slaying Tybalt.

In focusing on Dennis in this way, it is as though Longford is consciously identifying the author as the driving creative force behind the film – even more so than himself as director.

The couple are next seen at a cafe meeting with Ginger Mick and a friend (Harry Young) he has brought along, who immediately takes a shine to Doreen. Bill’s agitation turns to frothing rage when this ‘Stror ’at coot’, as he dubs him, is later found to be hanging around Doreen’s house and following her. Upon seeing them together, Bill loses his temper, threatens violence and chases his rival away. Doreen is disgusted with the behaviour of an unrepentant Bill, and, after a heated row, their courtship ends. ‘To call ’er back, I’ll never lift a ’and,’ says Bill.

A dejected Bill immediately returns to the ‘shick’. Time passes, and Ginger Mick attempts to cheer him up by inviting him to a party, which, as it turns out, Doreen also attends. Feelings between Doreen and Bill are rekindled as the former sings the song ‘The Curse of an Aching Heart’. Bill fends off the attentions of another of Doreen’s suitors, he walks her home, and they are reunited and consolidated.

Bill, who must now meet Doreen’s mother, ‘Mar’ (Margaret Reid), tries to better himself by studying such books as The Etiquette of Australia.[69]The Etiquette of Australia: A Handy Book of the Common Usages of Everyday Life and Society was written by Theodosia Ada Wallace. It was first published in 1909 and had three editions by 1922. See Robyn Arrowsmith, ‘Wallace, Theodosia Ada (1872–1953)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, 2005, <https://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/wallace-theodosia-ada-13234/text6733>, accessed 24 April 2021. Visiting her lavishly decorated home, he dons uncomfortable smart clothing for an awkward meeting, during which Doreen’s mother tearfully laments her late husband. By the end of the visit, Doreen and Bill are engaged.

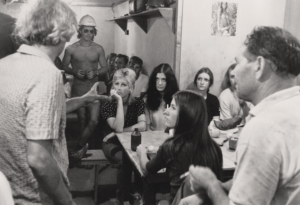

The couple get married in a church, followed by a well-attended and boisterous reception at Mar’s house. After a honeymoon, they settle into their ‘little home’, and there is happiness and harmony for two months. After that time, Bill one day bumps into Ginger Mick, who coaxes him into the pub, and an impromptu drinking binge ensues. The drinkers then visit another two-up game, where Bill again loses money. He stumbles home after 2am to an icy and silent Doreen. He is firmly in the doghouse, and is immediately remorseful. However, the next morning, Doreen wakes him and nurses his hangover – he is forgiven.

Mar then suddenly falls gravely ill and dies, leaving Doreen distraught. The couple, however, are able to move into Mar’s house, where they receive a letter from Doreen’s Uncle Jim (William Coulter) proposing to visit them. When he arrives, this jolly older man informs them he wants to retire from managing his fruit farm outside the city. He suggests Bill and Doreen take over the orchard and his home, and Bill enthusiastically agrees.

They move to the farm, and quickly settle into country life. However, Doreen also appears to become seriously ill, only for it to be revealed she is pregnant, and she gives birth to a son. Now thoroughly reconstructed and indeed ‘sentimental’, Bill reflects on his lot, Muldoon’s voice assuring us, ‘Ther ain’t no joy fer me beneath the blue / Unless I’m gazin’ lovin’ at them two.’

‘An outsider’s edge’: Paul Mac’s score

That plot summary has omitted mention or description of Mac’s new musical score. In the restored version of The Sentimental Bloke, this score can be regarded as at the very least a third major character, and at most as positioning Mac as a contributing force in the film almost on a par with Longford, Lyell, Dennis or Tauchert. It is an astounding piece of work, and is in tune perfectly with the film’s spectrum of moods and emotions: sad, energetic, playful, violent and, of course, sentimental.

Interestingly, Mac, best known for his career in electronic dance music and as a pop producer, did not even know the film existed prior to being approached by the NFSA to compose for it, giving him a detached perspective on the project that has surely contributed to the new score’s innovation and character. ‘My scores are probably a bit heavy-handed compared to proper film composers,’ says Mac, ‘but I think I bring an outsider’s edge that makes them sound unique. I’d love this score to be released as an album as it contains some of my best melodies, I reckon.’[70]Paul Mac, email interview with author. All further quotes from Mac are from this correspondence.

Of course, Mac is not the first to provide music for The Sentimental Bloke. On its initial release in 1919, there were live musical accompaniments, as was usual during the silent era. A newspaper article from November 1919 reports on a sixteen-piece orchestra and a male tenor singer performing at the Adelaide premiere.[71]‘The Sentimental Bloke’, The Advertiser, 18 November 1919, p. 9. One of the most popular musical accompaniments came from pianist Tom King, who played with the film on release in 1919 and whose score was recorded by the ABC in 1961. His soundtrack appeared on an NFSA video release of the film.[72]Butterss, op. cit., p. 208. The restored version of the film that appeared at the 2004 Sydney Film Festival featured a score composed by Jen Anderson (a musician who, perhaps thanks to a classical background, offered a more ‘traditional’ score than Mac’s).[73]Shirley, op. cit.

Mac’s score, which took him six months to complete, is replete with startling, dynamic moments that both serve the action and sometimes even divert the viewer’s attention away from the travails of Bill and Doreen, such is its colour and flamboyance. For example, the first time that synthesisers are heard, when Bill initially meets Doreen, is a considerable surprise, and firmly establishes the soundtrack as something flexible, unfixed in the silent era, and openly embracing modern styles and technology. Another delightful moment of synthesiser comes when the lovers are at Manly Beach, and Mac produces what he describes as ‘sparkles of synth’ to tie in with the stars coming out as day turns to night. This ethereal sonic quality returns on a number of occasions.

Another ‘concession to modernity’, as Mac puts it, brings one of the most extraordinary moments of the restored film. For about ten seconds during Doreen and Bill’s wedding reception, as guests dance and drink, Mac has provided loud, pounding techno music that some might describe as ‘doof’. This is a genuine laugh-out-loud moment, once you’ve gotten over the initial disorientation that this racket induces. Mac says that his score fell foul of a ‘few disgruntled purists’ at the 2020 premiere screening, but by including somewhat cheeky moments like this, he is actually in sync with the spirit of the original film and poem in terms of their wit and playfulness. Another section where this impishness is on display is when Bill is drunk after drowning his sorrows, and Mac employs effects to ‘slur’ the melody, with reverb to the fore, reflecting the wooziness of being ‘on the shick’. Similarly, later on, when Bill meets Mar, the music is discordant and wonky, in keeping with the awkwardness of the encounter.

All this should not give the impression that Mac abandoned the musical styles of the silent era – on the contrary, he embraced the period heartily. For example, at the party where Bill and Doreen are reunited, the score turns to a perky Scott Joplinesque, ragtime-influenced piano melody. Striking a balance was his priority. ‘I did some research and watched a few silent films,’ says Mac.

I wanted to match the action, particularly in fight scenes and slapstick stuff with the occasional timpani bend or scale run, but not end up fully ‘Mickey Mousing’ it. I like the balance between ‘this music could have been released in 1919’ versus ‘I’m going to cry now’ versus ‘falling off [the] seat laughing’.

Mac is particularly pleased with his achievements in the film’s most beloved scene, in which Bill and Doreen go to see Romeo and Juliet. Here, Mac quotes well-known traditional folk songs on harpsichord, but again, there is a drollness to the performance thanks to the use of staccato and the odd intentionally clunky note.

Mac’s instrumental palette – aside from the electronic elements – is rooted in ‘a chamber ensemble of piano, cello, bassoon, clarinet, trombone, saxophone, banjo and acoustic guitar.’ And from these tones, characterisation grew. ‘I improvised around the themes according to which character’s perspective we were experiencing them through,’ he says.

I ended up attaching bassoon to the Bloke, trombone to the drunks and flute to Doreen [… and wrote] new themes as characters were introduced and tried to keep them playful yet melancholic. I just wanted to match the playfulness of the original poetry.

Despite its complexities and diversity, the score’s centrepiece is undoubtedly its central motif or theme. This is a simple refrain initially based around three notes performed on piano. It is introduced over the opening credits and as we see Dennis at his desk. This theme bears the influence of ‘stride’ piano, a style that emerged out of ragtime; it also features the effect of a prominent appoggiatura – an ornamental, dissonant note that is quickly resolved to a regular note of the chord. The melody’s harmonic elements, which alternate between major and minor, are somewhat reminiscent of the sparse moments of piano in Yann Tiersen’s score for Amelie (Jean-Pierre Jeunet, 2001), and even Thomas Newman’s well-known (and overplayed) theme for American Beauty (Sam Mendes, 1999).

Mac’s main theme is a moving and beautiful tune, and perhaps what he is referring to when he says the score contains some of his best melodies. It exists in its most basic form at the film’s opening, and returns with an altered emotional cadence later on: when Doreen finds it within her to forgive Bill’s transgressions the morning after his bender with Ginger Mick; when Uncle Jim appears and the couple’s fortunes improve; and, most spectacularly, as the film concludes, when the melody is uplifted by strings, woodwind and sparkling synths, expanding into something ‘epic’ as Bill, Doreen and the new baby sit at sunset on the verandah of their country home. In this moment, it is Mac who drives the emotional energy of the scene, bringing immense catharsis as we celebrate Bill’s embrace of sentimentality.

‘Smilin’ tarts’: Language

The colloquial vernacular and working-class language of The Songs of a Sentimental Bloke have been pored over extensively in the 106 years since it was published,[74]See, for example, O’Reilly, op. cit. and need not be assessed again here. Suffice to say, though, it is a hoot to dwell in Dennis’ linguistic universe via the expressive delivery of Muldoon, who, Mac says, ‘gave an incredibly real voice to the Bloke’. It is hard not to raise a grin at the exuberant use of words like ‘bonzer’, ‘bosker’ and ‘ribuck’.

Dennis’ informality and slang actually presented problems for Mac, who says it was his decision to employ a narrator. ‘I really struggled with the intertitles,’ he says.

I really love the sound of CJ Dennis’ poetry. It’s so quintessentially Aussie, it’s all cheeky, fun and like no other nationality. It sounds so playful when you hear it. The problem was that I spent so much time reading the phonetically spelt, poetic intertitles written in old-time font, that I would have to pause the film to work out each card. [The narrator] also helped me jump between cues in the live show, and allowed the music to breathe a bit more.

Watching in 2021, certain aspects of Dennis’ language are certainly striking, and some word choices might be regarded as problematic. The word ‘tart’ is used regularly by Bill throughout the first half of the film: for instance, he watches the ‘smilin’ tarts’ as they go by in the Royal Botanic Gardens; Doreen is his ‘ideel tart’; he laments the ‘tarts that’s hard to get’.

Writing for The Guardian about the NFSA Restores version of The Sentimental Bloke, critic Luke Buckmaster categorised the use of ‘tarts’ as one way the language of the poem and film has dated.[75]Luke Buckmaster, ‘The Sentimental Bloke Turns 100: Australian Silent Film’s Enduring Masterpiece’, The Guardian, 16 November 2018, <https://www.theguardian.com/tv-and-radio/2018/nov/15/the-sentimental-bloke-turns-100-australian-silent-films-enduring-masterpiece>, accessed 24 April 2021. And yes: many viewers today will know the word as a pejorative and sexist term applied to women deemed to dress in a certain ‘provocative’ way or demonstrate a promiscuous nature (it can also have connotations related to sex work). However, to look at the history and evolution of the word is to reveal that a very different meaning was intended in The Sentimental Bloke. According to the Australian National University’s School of Literature, Language and Linguistics, ‘tart’ is an abbreviation of ‘jam tart’, itself rhyming slang for ‘sweetheart’. From the 1890s until the 1970s, the word meant ‘a girlfriend or sweetheart; also applied generally to a girl or woman, implying admiration’. It is also significant that ‘the use of tart to mean a girlfriend or sweetheart is unique to Australian English’.[76]‘Meanings and Origins of Australian Words and Idioms’, School of Literature, Language and Linguistics, Australian National University, <https://slll.cass.anu.edu.au/centres/andc/meanings-origins/all>, accessed 24 April 2021.

There are moments, however, when women are spoken about in more straightforwardly offensive terms where there can be no fallback on shifting etymology. Viewed through a modern lens, Bill becomes a rather unattractive character when he describes Mar as a ‘fat ole weepin’ willer’ and is repulsed by having to kiss his future mother-in-law. Towards the end of the film, he brands the woman (Helen Fergus) attending to Doreen as she gives birth a ‘fat ole nurse’.

Though not an issue of language, another disconcerting moment relating to Bill’s treatment of women occurs on Manly Beach. He is seen to rather manhandle Doreen, clutching her face in his hand in a way that looks not only uncomfortable for her, but also as if she is being dominated and restrained. The critic Julie Rigg sees Bill as ‘lifting up her face in a grip that almost mashes her jaw’.[77]Julie Rigg, ‘The Sentimental Bloke’, in Scott Hocking (ed.), 100 Greatest Films of Australian Cinema, Scribal, Richmond, Vic., 2006, p. 186. However, it is a physical gesture that Doreen in turn inflicts on Bill – albeit in a milder way – later on in a train carriage after their wedding, perhaps intended to be reflective of the changed power dynamic between them by this point: Bill is well on the way to being tamed.

A ‘low point’

The gravest, most troubling moment in The Sentimental Bloke’s intertitles comes with this passage:

Refreshed wiv Sleep day to the morning mill

Comes jauntily to out the nigger, Night.

Trained to the minute, confident in skill,

’E swaggers in the East, chock-full o’ skite.

The offensive term here appears on screen, but is, naturally, not spoken by Muldoon. O’Reilly describes this as the ‘low point’ of the original book.[78]O’Reilly, op. cit. Dennis is personifying day and night as combating Caucasian and Black boxers respectively, and the use of the word is arguably made worse by the fact that Dennis had specific fighters in mind: the unfortunate analogy was inspired by Jack Johnson’s win over Tommy Burns in Sydney in 1909, making the former the first African-American world heavyweight champion[79]Butterss, op. cit., p. 36. (a fight that, as it happened, Longford filmed[80]See Poppy de Souza, ‘Curator’s Notes’, in ‘Boxing 1908: Johnson vs Burns (1908)’, Australian Screen, <https://aso.gov.au/titles/historical/boxing-1908-johnson-vs-burns/notes/>, accessed 24 April 2021.).

The degree to which the use of such a word interferes with our appreciation of this very old film taps into one of the more complex and vexed questions of contemporary culture and entertainment. On the one hand, we must consider the milieu in which Dennis was writing and Longford was directing: in the early twentieth century, the slur was so common as to be used in the brand name of various commercial products in Australia.[81]See Bruce Lawrence Dennett, ‘The Genesis of Indigenous Australian Characterisations in Feature Films’, PhD thesis, Macquarie University, Sydney, New South Wales, 2012, p. 146. The word would have been an accepted part of mainstream culture. On the other hand, and perhaps this represents the final word on the issue, we can look to the comments of Netflix CEO Reed Hastings in the wake of him firing a communications executive for using the word in 2018:

For non-Black people, the word should not be spoken as there is almost no context in which it is appropriate or constructive (even when singing a song or reading a script). There is not a way to neutralize the emotion and history behind the word in any context.[82]Reed Hastings, quoted in Janko Roettgers, ‘Netflix Comms Chief Jonathan Friedland Out over Insensitive Comments’, Variety, 22 June 2018, <https://variety.com/2018/digital/news/netflix-cco-out-1202855305/>, accessed 24 April 2021.

In the context of this call for a lack of equivocation around the use of the word, one wonders whether it may have been possible for the NFSA Restores version of The Sentimental Bloke to edit out this particular intertitle, which is not essential to the plot.

‘It’s in the game’: Class

During Bill’s visit to meet Mar for the first time, there is a brief conversation about his name. She calls him ‘Willie’, which he dislikes, asking to be called Bill. She refuses to call him ‘that vulgar name’, and Bill relents, saying, ‘It’s in the game.’ In this clash over names, it is reinforced that Doreen comes from a higher social standing than Bill – and perhaps her initial standoffishness with him came from her regarding him as beneath her. Doreen’s social rung is further emphasised in the same scene by the elaborate ornaments and crockery in her mother’s house, and the disgust she expresses at the fact her daughter must work in a pickle factory (after the death of her husband, the family’s circumstances have been reduced).

In anticipation of Mar’s attitude, Bill tries to refine himself by reading The Etiquette of Australia, and his journey from aimless larrikin and petty criminal to farmer, businessman, husband and father is indicative of the fact that, in many ways, The Sentimental Bloke is about – or even a celebration of – social mobility (the capacity to move from one socio-economic standing to another). Film scholar Ina Bertrand suggests the message of the film is that class distinctions and prejudices can be overcome: ‘Bill’s function […] is to bridge social divisions – class, wealth and particularly gender.’[83]Ina Bertrand, quoted in Butterss, op. cit., p. 85.

The film’s elevated focus on class barriers and overcoming them is another important differentiation from Dennis’ original work. Butterss writes that, ‘The mise-en-scène contributes to the increased emphasis on upward mobility because it is able to capture Bill’s social origins in ways that were not possible on the printed page.’[84]Butterss, ibid., p. 151. The verse novel gives scant attention to Bill’s employment background, whereas the film takes care to identify him as unemployed, then a hawker, then working in a printery.[85]ibid. The scene in which Bill studies The Etiquette of Australia is also substantially reworked and made more prominent by Longford and Lyell in comparison with the original text. The reasons for such changes, in Butterss’ view, are twofold, and relate to changed social values between publication of the book and release of the film:

In an era of national rebuilding immediately after the war, the film’s sharper focus on success through hard work was a more relevant ideology than when the book had first been published. In addition, as the normative model of masculinity in Australia increasingly became that of the breadwinner, the film’s minor shifts allow the Bloke more room to demonstrate his credentials as a good provider for a household.[86]ibid., pp. 151–2.

The Sentimental Bloke is therefore, from the perspective of modern viewers, simultaneously progressive and conservative: in depicting how class divisions need not be cause for antagonism or stand in the way of relationships, Longford and Lyell convey a positive message; yet tailoring the film to the ideal of the man as provider and head of a household may seem narrow and outdated today.

Reception and aftermath

Definitive information on how well The Sentimental Bloke fared financially is elusive. However, the NFSA states the film broke box-office records upon release,[87]See ‘Background Information’, in ‘The Sentimental Bloke Film’, National Film and Sound Archive of Australia Digital Learning, <https://dl.nfsa.gov.au/module/348/>, accessed 24 April 2021. and Longford claimed in 1931 that the film had been made for A£900 and grossed A£50,000 internationally.[88]‘Australian Films: Earlier History’, The Daily News, 18 December 1931, p. 11. In Britain alone, it is reported to have earned A£36,000 when released there in 1922.[89]Butterss, op. cit., p. 153.

Critical reaction to the film was effusive. After opening night in Melbourne, The Argus proclaimed it the best moving picture Australia had ever produced; The Age described the work of cinematographer Arthur Higgins as ‘perfect’; and the UK film magazine Picture Show gave it the title of ‘Australia’s FIRST screen classic’.[90]All quoted in Butterss, ibid., p. 152. Indeed, some of the most gushing praise came from Britain – something that must surely have particularly pleased Longford and Lyell. After trade viewings, The Times wrote, ‘It is no exaggeration to say that it is one of the most completely successful comedies that have ever been put on the screen.’[91]Butterss, ibid., pp. 152–3. The Daily Express, meanwhile, wrote, ‘If Australia can keep up this standard, a new and very serious competitor will enter the world’s film markets.’[92]Quoted in Long & Long, op. cit., p. 42. There is one report that a leading English newspaper called The Sentimental Bloke ‘the greatest picture ever made’.[93]Sylvia Lawson, quoted in Eric Reade, History and Heartburn: The Saga of Australian Film 1896–1978, Harper & Row, Sydney, 1979, p. 21.

Another British review, in the trade paper The Bioscope, declared:

Acted quietly and naturally by players who perfectly embody the types they represent, the film has extraordinary charm. By its rich, shrewd humor and its simple humanity, it will certainly make as powerful an appeal to every class of audience as the famous British-film classic My Old Dutch [Laurence Trimble, 1915], with which it has been aptly compared.[94]Quoted in Pike & Cooper, op. cit., p. 120.

The film’s realism seems to have made a particularly large impact in the UK, with Kinematograph Weekly writing that it was as if the actors ‘are not players at all, but men and women of the slums, who, by some miracle performed by a master-producer, have been enabled to enact their lives before the camera’.[95]Quoted in Butterss, op. cit., p. 151.

The Australian journal The Triad called the film ‘very easily the best Australian picture yet’, and identified the performance by Lyell as particularly strong:

Doreen in the [book] charms us so little that we often feel like throwing things at her; but the little Australian girl who plays Doreen on the film is so sprightly and so honest, so womanly and so sweet, so unaffectedly Australian and human, that we found ourselves really believing in Doreen.[96]Susan Gloomish, ‘Still Among the Pictures’, The Triad, 10 November 1919, p. 30.

This review also notes that Tauchert ‘really looks the part’ of the Bloke.[97]ibid. Picture Show was also enthusiastic about Lyell, writing, ‘Longford might have searched the whole world over and not found anybody to equal Miss Lyell’s performance.’[98]Quoted in Wright, op. cit., p. 6. Of Tauchert, Green Room wrote he was ‘the Bloke of Blokes’.[99]Quoted in Melissa Bellanta, ‘A Masculine Romance: The Sentimental Bloke and Australian Culture in the War- and Early Interwar Years’, Journal of Popular Romance Studies, vol. 4, no. 2, 24 October 2014, <https://www.jprstudies.org/2014/10/a-masculine-romance-the-sentimental-bloke-and-australian-culture-in-the-war-and-early-interwar-yearsby-melissa-bellanta/>, accessed 24 April 2021.

Dennis’ reaction to the film was also, publicly at least,[100]Privately, Dennis told his publisher that the film ‘from an artistic point of view had many flaws in it’. Dennis, quoted in Butterss, op. cit., p. 149. one of delight. He enthused, ‘I cannot say how pleased I am at the faithful reproduction of the character,’[101]Butterss, ibid., p. 149. and wrote for the film’s promotional material, ‘The difficulties that I had foreseen have been overcome admirably, and turned into picture triumphs.’[102]Quoted in Butterss, ibid.

The Sentimental Bloke fared less well in America. Trade viewings took place there in late 1919, with a view to distribution by First National Pictures, a company with access to 5000 screens. The screenings were well received, but it was recommended that the intertitles be rewritten so that the Australian slang might be diluted and altered for American audiences.[103]Butterss, ibid., p. 163. Dennis did make these changes; some scenes were cut; and the film was renamed the underwhelming The Story of a Tough Guy,[104]See ‘Sentimental Bloke, The’, British Universities Film & Video Council website, <http://bufvc.ac.uk/shakespeare/index.php/title/av68827>, accessed 24 April 2021. but it wasn’t enough (Butterss writes that the ‘original magic was lost’[105]Butterss, op. cit., p. 163.). First National eventually rejected the film for public release.[106]ibid.

The story of the years between this disappointment in America and the rediscovery of the nitrate film in Melbourne in 1952 is immensely sad. Lyell, a true pioneer whose legacy is still felt today, died of tuberculosis at the age of thirty-five in 1925. Longford and Lyell enjoyed some success with the sequel to The Sentimental Bloke, Ginger Mick (1920), as well as other films, but the director was shattered by the loss of Lyell; and, without her as a creative partner, his career essentially fizzled out from that point on.[107]See Ina Bertrand, ‘Raymond Longford’s The Sentimental Bloke: The Restored Version’, Screening the Past, no. 26, December 2009, <http://www.screeningthepast.com/issue-26-reviews/raymond-longford%E2%80%99s-the-sentimental-bloke-the-restored-version/>, accessed 24 April 2021. In fact, he may have been on a downward curve even before Lyell’s death. Reviewing a return season of The Sentimental Bloke in Melbourne in 1923, one critic wrote, ‘The Bloke makes a perennial appeal to Australian audiences. The regret is that Raymond Longford has not seen fit to produce another picture to equal his great achievement.’[108]Quoted in Reade, History and Heartburn, op. cit., p. 38.

His leading man, too, died relatively young: Tauchert fell victim to cancer at the age of fifty-six in 1933. Emery died in 1934 and Dennis in 1938, meaning that, just twenty years after the film’s release, Longford was the only one of its five most well-known players left standing.[109]The contribution of Higgins, The Sentimental Bloke’s cinematographer, should not be underestimated. As well as the praise from The Argus, Byrnes writes, ‘Arthur Higgins’ cinematography has an almost documentary feel in some scenes, such as the wedding reception.’ Byrnes, op. cit. And, by that time, the ‘talkies’ had ensured his film was becoming a distant memory.[110]ibid.

Around the time the nitrate film was discovered in 1952, Longford was working as a watchman at Walsh Bay wharves. He reportedly had no interest in talking about his filmmaking past,[111]Shirley, op. cit. though associates recalled him being moved to tears when remembering Lyell.[112]See Wright, op. cit., p. 11. When the Sydney Film Festival screened The Sentimental Bloke in 1955, Longford was not invited, because the festival simply didn’t know he was still alive.[113]Shirley, op. cit. A reporter filled in the gaps for all parties, and Longford enjoyed some late-life recognition.[114]ibid. He died at the age of eighty in 1959.

Discussion of The Sentimental Bloke could go on ad infinitum. The acting performances of Lyell and Tauchert, for example, are worthy of lengthy studies in themselves: Tauchert’s portrayal of stress, anguish and worry on his crumpled face is a major highlight of the film; Lyell, meanwhile, exhibits extraordinary restraint and soulfulness, as well as a quiet fortitude, as she plays a character beautifully balanced between sweetness and strength.

Other avenues of analysis might be notions of masculinity,[115]See Bellanta, op. cit. Higgins’ adroit cinematography, how the film ties into the concept of ‘sentimental nationalism’[116]See Neville Buch, ‘The Dirge for a Sentimental Bloke’, Neville Buch author website, 20 May 2020, <https://drnevillebuch.com/the-dirge-for-a-sentimental-bloke/>, accessed 24 April 2021. and even the fashion choices on display.[117]See Jeannette Delamoir, ‘“I Dips Me Lid”: The Sentimental Bloke’s Hats’, Screening the Past, no. 36, June 2013,

<http://www.screeningthepast.com/issue-36-first-release/%E2%80%9Ci-dips-me-lid%E2%80%9D-the-sentimental-bloke%E2%80%99s-hats/>, accessed 24 April 2021. That The Sentimental Bloke remains ripe for so much deliberation and debate is testament to Longford and Lyell’s vision, this being without question their greatest triumph – as well as, undoubtedly, the pinnacle of Australian silent film.

Select bibliography

‘The Sentimental Bloke’, Living History with Mat McLachlan, 5 February 2020, <https://podcasts.apple.com/at/podcast/living-history-with-mat-mclachlan/id1317242813>.

Melissa Bellanta, ‘A Masculine Romance: The Sentimental Bloke and Australian Culture in the War- and Early Interwar Years’, Journal of Popular Romance Studies, vol. 4, no. 2, 24 October 2014, <https://www.jprstudies.org/2014/10/a-masculine-romance-the-sentimental-bloke-and-australian-culture-in-the-war-and-early-interwar-yearsby-melissa-bellanta/>.

Ina Bertrand, ‘Raymond Longford’s The Sentimental Bloke: The Restored Version’, Screening the Past, no. 26, December 2009, <http://www.screeningthepast.com/issue-26-reviews/raymond-longford%E2%80%99s-the-sentimental-bloke-the-restored-version/>.

Philip Butterss, An Unsentimental Bloke: The Life and Work of C.J. Dennis, Wakefield Press, Adelaide, 2014.

Paul Byrnes, ‘Curator’s Notes’, in ‘The Sentimental Bloke (1919)’, Australian Screen, <https://aso.gov.au/titles/features/sentimental-bloke/notes/>.

Bronwyn Coupe, Jennifer Coombes & Tenille Hands, ‘Women Leaders in Film: Lottie Lyell, the McDonagh Sisters and Rachel Perkins’, National Film and Sound Archive of Australia website, 28 February 2014, <https://www.nfsa.gov.au/latest/women-film-lottie-lyell>.

Ray Edmondson & Andrew Pike, Australia’s Lost Films: The Loss and Rescue of Australia’s Silent Cinema, National Library of Australia, Canberra, 1982.

Scott Hocking (ed.), 100 Greatest Films of Australian Cinema, Scribal, Richmond, Vic., 2006.

Joan Long & Martin Long, The Pictures That Moved: A Picture History of the Australian Cinema 1896–1929, Hutchinson, Richmond, Vic., 1982.

Margot Nash, ‘Lottie Lyell’, Women Film Pioneers Project, 2018, <https://wfpp.columbia.edu/pioneer/lottie-lyell/>.

Margot Nash, ‘Lottie Lyell: The Silent Work of an Early Australian Scenario Writer’, Screening the Past, no. 40, September 2015, <http://www.screeningthepast.com/issue-40-first-release/lottie-lyell-the-silent-work-of-an-early-australian-scenario-writer/>.

Andrew Pike & Ross Cooper, Australian Film, 1900–1977: A Guide to Feature Film Production, Oxford University Press & Australian Film Institute, Melbourne, 1980.

Eric Reade, Australian Silent Films: A Pictorial History of Silent Films from 1896 to 1929, Lansdowne Press, Melbourne, 1970.

Eric Reade, History and Heartburn: The Saga of Australian Film 1896–1978, Harper & Row, Sydney, 1979.

Graham Shirley, ‘How the NFSA Restored and Re-released The Bloke’, National Film and Sound Archive of Australia website, 5 August 2011, <https://www.nfsa.gov.au/latest/sentimental-bloke>.

Andrée Wright, Brilliant Careers: Women in Australian Cinema, Pan Books, Sydney, 1986.

MAIN CAST

Bill, the Bloke Arthur Tauchert Doreen Lottie Lyell Ginger Mick Gilbert Emery Stror ’at Coot Harry Young The Bloke’s friend Stanley Robinson Mar Margaret Reid Uncle Jim William Coulter Parson Charles Keegan Nurse Helen Fergus CJ Dennis CJ Dennis

PRINCIPAL CREDITS

Year of release 1919 Length 107 minutes Director Raymond Longford Screenplay Raymond Longford & Lottie Lyell Production Company Southern Cross Feature Film Company Producer Raymond Longford Director of Photography Arthur Higgins Editor Lottie Lyell Assistant Directors Arthur Cross & Clyde Marsh

Endnotes

| 1 | Harrison Bryan, ‘Preface’, in Ray Edmondson & Andrew Pike, Australia’s Lost Films: The Loss and Rescue of Australia’s Silent Cinema, National Library of Australia, Canberra, 1982, p. 5. |

|---|---|

| 2 | See Monique Fischer, ‘A Short Guide to Film Base Photographic Materials: Identification, Care, and Duplication’, Northeast Document Conservation Center website, 2020, <https://www.nedcc.org/free-resources/preservation-leaflets/5.-photographs/5.1-a-short-guide-to-film-base-photographic-materials-identification,-care,-and-duplication>, accessed 20 April 2021. |

| 3 | See ‘History of Film Types Timeline’, National Park Service website, updated 18 December 2019, <https://www.nps.gov/subjects/hfc/history-of-film-types-timeline.htm>, accessed 20 April 2021. |

| 4 | The photo is a still from the film Joe (Beaumont Smith, 1924). See Edmondson & Pike, op. cit., p. 2. |

| 5 | The silent-film era can be regarded as spanning 1894 to 1929. See Donna Kornhaber, ‘Silent Film’, Oxford Bibliographies, 2020, <https://www.oxfordbibliographies.com/view/document/obo-9780199791286/obo-9780199791286-0223.xml>, accessed 21 April 2021. |

| 6 | See ‘NFSA’s Most Wanted’, National Film and Sound Archive of Australia website, 13 September 2016, <https://www.nfsa.gov.au/nfsa-most-wanted>, accessed 21 April 2021. |

| 7 | Edmondson & Pike, op. cit., p. 9. |

| 8 | Joan Long & Martin Long, The Pictures That Moved: A Picture History of the Australian Cinema 1896–1929, Hutchinson, Richmond, Vic., 1982, p. 11. |

| 9 | Elena Guest, in ‘The Sentimental Bloke’, Living History with Mat McLachlan, 5 February 2020, <https://podcasts.apple.com/at/podcast/living-history-with-mat-mclachlan/id1317242813>, accessed 21 April 2021. |

| 10 | See ‘“Lost” Silent Films to be Restored’, ABC News, 24 April 2008, <https://www.abc.net.au/news/2008-04-24/lost-silent-films-to-be-restored/2414434>, accessed 21 April 2021. |

| 11 | Graham Shirley, ‘How the NFSA Restored and Re-released The Bloke’, National Film and Sound Archive of Australia website, 5 August 2011, <https://www.nfsa.gov.au/latest/sentimental-bloke>, accessed 21 April 2021. |

| 12 | See ‘100 Years of Film Australia’, National Film and Sound Archive of Australia website, 15 April 2013, <https://www.nfsa.gov.au/latest/film-australia-chronology>, accessed 22 April 2021. |

| 13 | See Long & Long, op. cit., p. 64. |

| 14 | Shirley, op. cit. |

| 15 | ibid. |

| 16 | ibid. |

| 17 | ibid. |

| 18 | ‘Paul Mac Creates New Music for 100-year-old Film The Sentimental Bloke’, media release, National Film and Sound Archive of Australia, 14 January 2020, <https://www.nfsa.gov.au/paul-mac-creates-new-music-100-year-old-film-sentimental-bloke>, accessed 22 April 2021. |

| 19 | Nathanael O’Reilly, ‘Nathanael O’Reilly Reviews The Songs of a Sentimental Bloke and Searching for The Man from Snowy River’, Cordite Poetry Review, 1 September 2013, <http://cordite.org.au/reviews/oreilly-dennis-refshauge/>, accessed 22 April 2021. |

| 20 | ‘The Songs of a Sentimental Bloke’, AustLit, updated 29 November 2019, <https://www.austlit.edu.au/austlit/page/C204825>, accessed 22 April 2021. |

| 21 | ibid. |

| 22 | Not everyone was impressed: artist Norman Lindsay loathed The Songs of a Sentimental Bloke so much that he ‘crucified’ a copy on a homemade cross in his front garden. See Philip Butterss, An Unsentimental Bloke: The Life and Work of C.J. Dennis, Wakefield Press, Adelaide, 2014, p. 79. |

| 23 | ‘The Songs of a Sentimental Bloke’, op. cit. |

| 24 | Butterss, op. cit., p. 37. |

| 25 | ibid. |

| 26 | ibid., pp. 73–4. |

| 27 | Long & Long, op. cit., p. 36. |

| 28 | Eric Reade, Australian Silent Films: A Pictorial History of Silent Films from 1896 to 1929, Lansdowne Press, Melbourne, 1970, p. 180. |

| 29 | Eric Reade writes of Sweet Nell of Old Drury, ‘No doubt Raymond Longford found this one of his most rewarding films as a director.’ Ibid., p. 62. |

| 30 | Andrée Wright, Brilliant Careers: Women in Australian Cinema, Pan Books, Sydney, 1986, p. 2. |

| 31 | ibid. |

| 32 | ibid., p. 5. |

| 33 | Margot Nash, ‘Lottie Lyell’, Women Film Pioneers Project, 2018, <https://wfpp.columbia.edu/pioneer/lottie-lyell/>, accessed 23 April 2021. |

| 34 | Shirley, op. cit. Wright offers different numbers, writing, ‘Lottie Lyell worked on at least twenty-eight films with her partner Raymond Longford, and acted in twenty-one of them.’ Wright, op. cit., p. 2. |

| 35 | Wright, op. cit., p. 10. |

| 36 | Margot Nash, ‘Lottie Lyell: The Silent Work of an Early Australian Scenario Writer’, Screening the Past, no. 40, September 2015, <http://www.screeningthepast.com/issue-40-first-release/lottie-lyell-the-silent-work-of-an-early-australian-scenario-writer/>, accessed 24 April 2021. |

| 37 | Long & Long, op. cit., p. 36. |

| 38 | The Longford Lyell Award, the highest honour that the Australian Academy of Cinema and Television Arts can bestow on an individual, changed its name from the Raymond Longford Award in 2015 ‘in recognition of Raymond Longford’s partner in filmmaking and in life, Lottie Lyell’. See ‘Longford Lyell Award’, Australian Academy of Cinema and Television Arts website, <https://www.aacta.org/aacta-awards/longford-lyell-award/>, accessed 24 April 2021. |

| 39 | Nash, ‘Lottie Lyell’, op. cit. |

| 40 | See Bronwyn Coupe, Jennifer Coombes & Tenille Hands, ‘Women Leaders in Film: Lottie Lyell, the McDonagh Sisters and Rachel Perkins’, National Film and Sound Archive of Australia website, 28 February 2014, <https://www.nfsa.gov.au/latest/women-film-lottie-lyell>, accessed 24 April 2021. |

| 41 | Butterss, op. cit., p. 137. |

| 42 | Raymond Longford, quoted in Wright, op. cit., p. 6. |

| 43 | Wright, ibid., p. 6. |

| 44 | Butterss, op. cit., p. 137. |

| 45 | ibid. |

| 46 | ibid., pp. 137–8. |

| 47 | CJ Dennis, quoted in Butterss, op. cit., p. 139. |

| 48 | See Andrew Pike & Ross Cooper, Australian Film, 1900–1977: A Guide to Feature Film Production, Oxford University Press & Australian Film Institute, Melbourne, 1980, p. 119. |

| 49 | ibid., p. 122. |

| 50 | Butterss, op. cit., p. 150. |

| 51 | Raymond Longford, quoted in Pike & Cooper, op. cit., p. 122. |

| 52 | ‘The Fatal Wedding: A Crowded House’, Northern Star, 26 August 1910, p. 2. |

| 53 | Pike & Cooper, op. cit., p. 120. |

| 54 | ibid. |

| 55 | ibid. |

| 56 | Butterss, op. cit., p. 150. |

| 57 | Guest, op. cit. |

| 58 | Paul Byrnes, ‘Curator’s Notes’, in ‘The Sentimental Bloke (1919)’, Australian Screen, <https://aso.gov.au/titles/features/sentimental-bloke/notes/>, accessed 24 April 2021. |

| 59 | See ‘The Slums of Sydney’, The Sunday Times, 18 January 1920, p. 3. |

| 60 | Long & Long, op. cit., p. 41. |

| 61 | See Pike & Cooper, op. cit., p. 120. |

| 62 | See Einar Docker, ‘Where Is Wonderland? – Tamarama’s Secret Past’, Museum of Applied Arts & Sciences, 28 August 2013, <https://maas.museum/inside-the-collection/2013/08/28/where-is-wonderland-tamaramas-secret-past/>, accessed 24 April 2021. |

| 63 | Butterss, op. cit., p. 150. |

| 64 | Pike & Cooper, op. cit., p. 120. |

| 65 | Butterss, op. cit., p. 152. |

| 66 | Pike & Cooper, op. cit., p. 120. |

| 67 | ibid. |

| 68 | Butterss, op. cit., pp. 152–3. |

| 69 | The Etiquette of Australia: A Handy Book of the Common Usages of Everyday Life and Society was written by Theodosia Ada Wallace. It was first published in 1909 and had three editions by 1922. See Robyn Arrowsmith, ‘Wallace, Theodosia Ada (1872–1953)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, 2005, <https://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/wallace-theodosia-ada-13234/text6733>, accessed 24 April 2021. |

| 70 | Paul Mac, email interview with author. All further quotes from Mac are from this correspondence. |

| 71 | ‘The Sentimental Bloke’, The Advertiser, 18 November 1919, p. 9. |

| 72 | Butterss, op. cit., p. 208. |

| 73 | Shirley, op. cit. |

| 74 | See, for example, O’Reilly, op. cit. |

| 75 | Luke Buckmaster, ‘The Sentimental Bloke Turns 100: Australian Silent Film’s Enduring Masterpiece’, The Guardian, 16 November 2018, <https://www.theguardian.com/tv-and-radio/2018/nov/15/the-sentimental-bloke-turns-100-australian-silent-films-enduring-masterpiece>, accessed 24 April 2021. |

| 76 | ‘Meanings and Origins of Australian Words and Idioms’, School of Literature, Language and Linguistics, Australian National University, <https://slll.cass.anu.edu.au/centres/andc/meanings-origins/all>, accessed 24 April 2021. |

| 77 | Julie Rigg, ‘The Sentimental Bloke’, in Scott Hocking (ed.), 100 Greatest Films of Australian Cinema, Scribal, Richmond, Vic., 2006, p. 186. |

| 78 | O’Reilly, op. cit. |

| 79 | Butterss, op. cit., p. 36. |

| 80 | See Poppy de Souza, ‘Curator’s Notes’, in ‘Boxing 1908: Johnson vs Burns (1908)’, Australian Screen, <https://aso.gov.au/titles/historical/boxing-1908-johnson-vs-burns/notes/>, accessed 24 April 2021. |

| 81 | See Bruce Lawrence Dennett, ‘The Genesis of Indigenous Australian Characterisations in Feature Films’, PhD thesis, Macquarie University, Sydney, New South Wales, 2012, p. 146. |

| 82 | Reed Hastings, quoted in Janko Roettgers, ‘Netflix Comms Chief Jonathan Friedland Out over Insensitive Comments’, Variety, 22 June 2018, <https://variety.com/2018/digital/news/netflix-cco-out-1202855305/>, accessed 24 April 2021. |

| 83 | Ina Bertrand, quoted in Butterss, op. cit., p. 85. |

| 84 | Butterss, ibid., p. 151. |

| 85 | ibid. |

| 86 | ibid., pp. 151–2. |

| 87 | See ‘Background Information’, in ‘The Sentimental Bloke Film’, National Film and Sound Archive of Australia Digital Learning, <https://dl.nfsa.gov.au/module/348/>, accessed 24 April 2021. |

| 88 | ‘Australian Films: Earlier History’, The Daily News, 18 December 1931, p. 11. |

| 89 | Butterss, op. cit., p. 153. |

| 90 | All quoted in Butterss, ibid., p. 152. |

| 91 | Butterss, ibid., pp. 152–3. |

| 92 | Quoted in Long & Long, op. cit., p. 42. |

| 93 | Sylvia Lawson, quoted in Eric Reade, History and Heartburn: The Saga of Australian Film 1896–1978, Harper & Row, Sydney, 1979, p. 21. |

| 94 | Quoted in Pike & Cooper, op. cit., p. 120. |

| 95 | Quoted in Butterss, op. cit., p. 151. |

| 96 | Susan Gloomish, ‘Still Among the Pictures’, The Triad, 10 November 1919, p. 30. |

| 97 | ibid. |

| 98 | Quoted in Wright, op. cit., p. 6. |

| 99 | Quoted in Melissa Bellanta, ‘A Masculine Romance: The Sentimental Bloke and Australian Culture in the War- and Early Interwar Years’, Journal of Popular Romance Studies, vol. 4, no. 2, 24 October 2014, <https://www.jprstudies.org/2014/10/a-masculine-romance-the-sentimental-bloke-and-australian-culture-in-the-war-and-early-interwar-yearsby-melissa-bellanta/>, accessed 24 April 2021. |

| 100 | Privately, Dennis told his publisher that the film ‘from an artistic point of view had many flaws in it’. Dennis, quoted in Butterss, op. cit., p. 149. |

| 101 | Butterss, ibid., p. 149. |

| 102 | Quoted in Butterss, ibid. |

| 103 | Butterss, ibid., p. 163. |

| 104 | See ‘Sentimental Bloke, The’, British Universities Film & Video Council website, <http://bufvc.ac.uk/shakespeare/index.php/title/av68827>, accessed 24 April 2021. |

| 105 | Butterss, op. cit., p. 163. |

| 106 | ibid. |

| 107 | See Ina Bertrand, ‘Raymond Longford’s The Sentimental Bloke: The Restored Version’, Screening the Past, no. 26, December 2009, <http://www.screeningthepast.com/issue-26-reviews/raymond-longford%E2%80%99s-the-sentimental-bloke-the-restored-version/>, accessed 24 April 2021. |

| 108 | Quoted in Reade, History and Heartburn, op. cit., p. 38. |

| 109 | The contribution of Higgins, The Sentimental Bloke’s cinematographer, should not be underestimated. As well as the praise from The Argus, Byrnes writes, ‘Arthur Higgins’ cinematography has an almost documentary feel in some scenes, such as the wedding reception.’ Byrnes, op. cit. |

| 110 | ibid. |

| 111 | Shirley, op. cit. |

| 112 | See Wright, op. cit., p. 11. |

| 113 | Shirley, op. cit. |

| 114 | ibid. |

| 115 | See Bellanta, op. cit. |

| 116 | See Neville Buch, ‘The Dirge for a Sentimental Bloke’, Neville Buch author website, 20 May 2020, <https://drnevillebuch.com/the-dirge-for-a-sentimental-bloke/>, accessed 24 April 2021. |

| 117 | See Jeannette Delamoir, ‘“I Dips Me Lid”: The Sentimental Bloke’s Hats’, Screening the Past, no. 36, June 2013, <http://www.screeningthepast.com/issue-36-first-release/%E2%80%9Ci-dips-me-lid%E2%80%9D-the-sentimental-bloke%E2%80%99s-hats/>, accessed 24 April 2021. |