Making its world premiere at the Melbourne International Film Festival in August 2020, documentary Looky Looky Here Comes Cooky (Steven McGregor) opens a dialogue to re-examine James Cook’s arrival in Australia – an event whose 250th anniversary was also marked last year – from an Indigenous perspective. The film flips the Cook narrative to what presenter and co-writer Steven Oliver calls ‘the view from the shore’, pointing out that, instead, ‘we’ve always been told the perspective of the view from the ship’.[1]Steven Oliver, in Looky Looky Here Comes Cooky post-screening Q&A, Brisbane International Film Festival, 3 October 2020.

As Oliver follows Cook’s landing and journey up the eastern coast of Australia, the Indigenous perspective is expressed through a specially commissioned songline, providing emotional responses and reflections to these historical events. Acclaimed Ngarrindjeri composer and performer Daniel Rankine (aka Trials) explains that, for Indigenous people, songlines represent both ‘where we’re from and, most importantly, where we’re going’; accordingly, a range of artists with diverse musical styles have been brought together for the film, with their music produced by Rankine. Along with his own featured track, ‘Colour Me Bad’, he produces additional music for the film, creating a varied yet holistic soundscape. The songs’ performances are shot music-video style, broken up with studio footage of the creative process and interviews with the artists. Location is important to all of the song clips, which are predominantly shot outdoors, with sensational aerial photography of coastal and interior landscapes highlighting the connection to country that is thematically entrenched in so many of the songs.

Hip-hop track ‘Colour Me Bad’ is the first of the film’s songs. Rankine states that he sees his work as speaking predominantly to white Australia, expressing a desire to reach young people through his music by connecting historical and contemporary viewpoints. This includes weaving in stories of his own childhood in Raukkan, South Australia, with what he calls the ‘echoes of colonisation’ that permeate his music.

‘Bagi-la-m Bargan’, a track by Butchulla hip-hop artist Nathan Bird (who performs as Birdz) foregrounds the view from the shore. In interview, he has described the song as having been inspired by the ‘active Aboriginal resistance against European invasion’ – a resistance that ‘the dominant narrative of Australian history neglects’.[2]Nathan Bird, quoted in Emily Nicol, ‘Birdz Drops New Single Looking at Arrival of Cook’, NITV News,20 August 2020, <https://www.sbs.com.au/nitv/article/2020/08/19/birdz-drops-new-single-looking-arrival-cook>, accessed 3 March 2021. The track also features a relative of Bird’s, fellow musician Fred Leone, singing in Badjala language. In a Q&A following the film’s Brisbane International Film Festival (BIFF) screening, Leone spoke of the importance of songlines in passing down language and stories from ‘an unbroken line of ancestors’. In creating this song, he said, he and Bird wanted ‘people to not just hear it, but to feel the power of what our stories are’.[3]Fred Leone, Looky Looky Here Comes Cooky post-screening Q&A, op. cit.

Indigenous language also features in Wergaia/Wembawemba singer/songwriter Alice Skye’s hauntingly beautiful ‘Wurega Djalin’. Skye wrote the track in response to the ‘sadness and anger’ she has felt about her family’s experience at Victoria’s Ebenezer Mission. The loss of languages through the missionary system, and through colonisation generally, drove her to sing part of the song in Wergaia – the first time she has done so in her music. She says in the film that the song reflects the process of learning her Indigenous language in order to get more in touch with her own culture, as loss of language equates to loss of connection to country and clan.

‘Far Away’ offers a female perspective on the view from the shore, seen through the eyes of a traditional healer who foresees the coming of the invaders. Its composer, Wiradjuri/Visayan musician Mojo Ruiz de Luzuriaga (aka Mo’Ju), describes Cook as the ‘poster boy for colonisation’ and, like others in the film, laments the ‘whitewashed’ version of history she learned at school. She sees her music as an important opportunity to reflect on historical events and express ‘the story of what that Black experience looks like in 2020’. Her track is accompanied by archival stills and footage of the Indigenous-rights movement in Australia.

Regarding ‘the constant denial of us and our existence’ that Oliver says has permeated white Australian history, legendary Murri singer/songwriter Kev Carmody says, ‘You could write another hundred bloody thousand songs about it.’ He laments that this feeling still exists in 2020, and that the need to fight it is as strong as ever. His song ‘Multugerrah’, co-written with his son Paul, shares a story of active resistance, rejecting the notion of passive acceptance of colonisation that is historically taught; as Paul puts it, ‘The keys were never handed over.’

The final song, by Torres Strait Islander Patrick Mau (aka Mau Power), is the stirring call to action ‘Stand Up’. The way Mau learned about Cook and the ‘discovery’ of Australia at high school, and his sense that this was not the whole story, led him on his own journey of learning about Indigenous history. He states in the film that his music acknowledges ‘pain and loss, anger and hatred, all mixed into one’ with its theme of first contact and the impact of the past on the present. Ultimately, his message – ‘Let’s move together to a better nation’ – mirrors that of the other artists and the overall theme of the documentary.

We simply can’t escape Cook, but the film doesn’t want us to; while acknowledging the polarised view of Cook as discoverer/invader, it also accepts that he holds a valid place in our history.

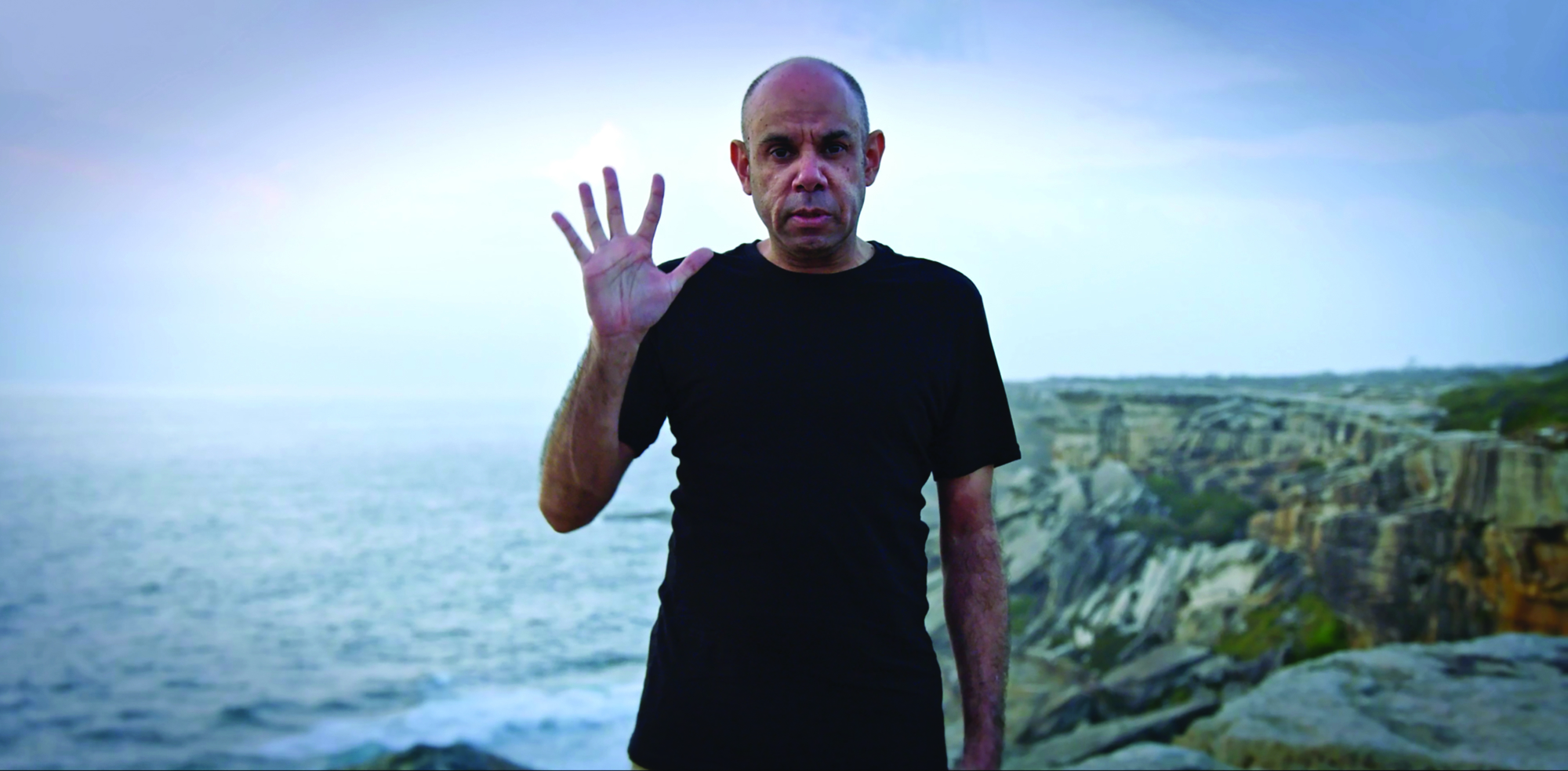

A number of other interviewees with connections to the geographical locations on Cook’s journey aim to fill in the narrative gaps, and, on occasion, overturn colonialist claims in what many of us know as Cook’s story. These include Dharawal elder Shayne Williams, La Perouse Local Aboriginal Land Council chair Noeleen Timbery, National Trust of Australia (Queensland)’s Harold Ludwick, Kaurareg elder Waubin Aken and Guugu Yimidhirr–nation historian Alberta Hornsby. Oliver’s thoughtful questioning brings gravitas to the interviews without allowing his own big personality to overshadow the interviewees. He also contributes artistically to the film with his powerful poetry. His first spoken-word performance, delivered direct to camera from a spectacular clifftop, comes at the halfway point of the film. This acts as a kind of punctuation mark, his poem highlighting the convergence of the past and present; as the poem states, ‘250 years, and we’re facing the same hurdles.’ He performs again later in the film, sharing his poem ‘I’m a Blackfella’, before taking the narrative into a debate on Australia’s impending celebrations of Cook’s landing, and the groundswell of Black and white voices that position these events as a barrier to true reconciliation.

The theme of education – and, more specifically, re-education – naturally emerges throughout the film. A question asked of many of the interviewees is what they recall learning about Cook while at school. Unfortunately, their answers are unsurprisingly similar, with the Indigenous perspective largely absent from their formal education, and Cook framed as a brave adventurer who discovered, rather than facilitated the invasion of, Australia. While recounting his journey, Oliver cheekily refers to Cook as ‘Uncle Jimmy James’, stripping away the reverence that European history books have attributed to the ‘legend’ of Cook. There are many obvious ways to approach the film with students of all ages and from multidisciplinary perspectives: history, music, art (the film employs what interviewer Dean Gibson described at the BIFF Q&A as ‘Monty Pythonesque’[4]Dean Gibson, Looky Looky Here Comes Cooky post-screening Q&A, ibid. animation) and poetry. Oliver himself has expressed hope that the film will reach young viewers sooner rather than later, joking in interview that he should ‘get on the phone and tell the education department, “You should put this on the curriculum.”’[5]Steven Oliver, quoted in Carly Williams, ‘Steven Oliver Challenges Australia’s Blurred Vision of Captain Cook with New Documentary’, HuffPost Australia, 19 August 2020, <https://www.huffingtonpost.com.au/entry/steven-oliver-looky-looky-here-comes-cooky_au_5f3c8098c5b683523603697c>, accessed 3 March 2021. Minor modification of punctuation. Recalling his time working as a performer in schools, he has expressed the notion that children have a capacity for ‘compassion and learning’ that often outweighs that of adults, stemming from their ‘natural empathy’ and connection with their emotions.[6]Oliver, Looky Looky Here Comes Cooky post-screening Q&A, op. cit.

However, as such an accessible and enjoyable film, Looky Looky Here Comes Cooky’s educative aspects would ideally also serve the wider community. Being an Australian of European descent, I found that the film spoke to me in an entertaining and informative way; those who are open to hearing other perspectives on our country’s colonial history are met with a moving, funny and overall enriching experience. Even though the film runs the gamut of emotions, it is the use of humour driven by Oliver that allows a way into the material for all kinds of viewers. In an interview with The Sydney Morning Herald, he states,

There’s anger in the documentary, but it’s not like we just sit around festering. And we still laugh. We have a great sense of humour. My hope for this documentary is that it starts a discussion, not a screaming match.[7]Steven Oliver, quoted in Bridget McManus, ‘Steven Oliver Gets Serious with Looky Looky Here Comes Cooky’, The Sydney Morning Herald,15 August 2020, <https://www.smh.com.au/culture/tv-and-radio/steven-oliver-gets-serious-with-looky-looky-here-comes-cooky-20200806-p55j5e.html>, accessed 3 March 2021.

The film recognises Cook’s ‘enduring mark’[8]Heidi Norman, ‘Looky Looky Here Comes Cooky: The “View from the Shore” Told Through Songlines, with Generosity’, The Conversation, 18 August 2020, <https://theconversation.com/looky-looky-here-comes-cooky-the-view-from-the-shore-told-through-songlines-with-generosity-144065>, accessed 3 March 2021. on Australia, evident in the naming of everything from towns to pubs with the explorer’s moniker. We simply can’t escape Cook, but the film doesn’t want us to; while acknowledging the polarised view of Cook as discoverer/invader, it also accepts that he holds a valid place in our history. Rather, at its heart, the film aims to redress the balance in the telling of Cook’s story. Indigenous opinions about him are not necessarily always steeped in loathing; Hornsby expresses her respect for Cook’s scientific prowess during her interview, describing him as a man ‘reaching for the stars’. Oliver reflects that her comments remind the audience that ‘we’re diverse people with diverse opinions’.[9]Oliver, Looky Looky Here Comes Cooky post-screening Q&A, op. cit. He also reminds viewers of the importance of the explorer’s mapping and navigational advancements, as well as the ‘courage and self-belief’ he must have had. Timbery reiterates that owning our history, good and bad, is the key to moving forward as a nation. History cannot be viewed as a fixed or finite entity; all examinations of history are open to reinterpretation and exploration, and the time for doing this in Australia is long overdue. As Ludwick states near the film’s end, ‘The whole story of Cook has not finished. It will never finish until we add the bookend: our story of it.’

Exploring Cook’s story through poetry and song is more than just an artistic choice or a way to showcase Indigenous talent, although it is successful on both these counts. As Oliver states in the film, songlines ‘are important to this nation, if we are ever going to meet in the middle’. Writing for screenhub, Zagareb/Dauareb storyteller Vika Mana says of the film,

Each of [the featured artists’] songs lead viewers to another history lesson, and another point in time, thus bringing our perspectives to the forefront […] It’s almost a healing experience, to have our truths illustrated with no colonial constraints.[10]Vika Mana, ‘TV Review: Looky Looky Here Comes Cooky Is Unapologetically Black’, screenhub, 20 August 2020,<https://www.screenhub.com.au/news-article/reviews/film/vika-mana/tv-review-looky-looky-here-comes-cooky-is-unapologetically-black-260938>, accessed 3 March 2021. Minor modification of punctuation.

Although Cook’s travels provide a chronological throughline, the film is episodic in structure, with each of the performances and additional interviews taking us on their own mini narrative journeys. The film’s structure presents the historical accounts as a mosaic of events, rather than as a purely linear historical narrative.

In the final line of his poem ‘I’m a Blackfella’, Oliver asks, ‘Are you part of a country’s problem … or the solution?’ Researcher Heidi Norman points out that the multiple viewpoints in Looky Looky Here Comes Cooky ‘offer the possibility of a different Australia with a more truthful engagement with its history’.[11]Norman, op. cit. The film invites all Australians to be a part of the solution by owning and relearning our history, asking questions, and examining the past through others’ eyes – so that we may ultimately look through our own towards a future of true reconciliation and healing.

Endnotes

| 1 | Steven Oliver, in Looky Looky Here Comes Cooky post-screening Q&A, Brisbane International Film Festival, 3 October 2020. |

|---|---|

| 2 | Nathan Bird, quoted in Emily Nicol, ‘Birdz Drops New Single Looking at Arrival of Cook’, NITV News,20 August 2020, <https://www.sbs.com.au/nitv/article/2020/08/19/birdz-drops-new-single-looking-arrival-cook>, accessed 3 March 2021. |

| 3 | Fred Leone, Looky Looky Here Comes Cooky post-screening Q&A, op. cit. |

| 4 | Dean Gibson, Looky Looky Here Comes Cooky post-screening Q&A, ibid. |

| 5 | Steven Oliver, quoted in Carly Williams, ‘Steven Oliver Challenges Australia’s Blurred Vision of Captain Cook with New Documentary’, HuffPost Australia, 19 August 2020, <https://www.huffingtonpost.com.au/entry/steven-oliver-looky-looky-here-comes-cooky_au_5f3c8098c5b683523603697c>, accessed 3 March 2021. Minor modification of punctuation. |

| 6 | Oliver, Looky Looky Here Comes Cooky post-screening Q&A, op. cit. |

| 7 | Steven Oliver, quoted in Bridget McManus, ‘Steven Oliver Gets Serious with Looky Looky Here Comes Cooky’, The Sydney Morning Herald,15 August 2020, <https://www.smh.com.au/culture/tv-and-radio/steven-oliver-gets-serious-with-looky-looky-here-comes-cooky-20200806-p55j5e.html>, accessed 3 March 2021. |

| 8 | Heidi Norman, ‘Looky Looky Here Comes Cooky: The “View from the Shore” Told Through Songlines, with Generosity’, The Conversation, 18 August 2020, <https://theconversation.com/looky-looky-here-comes-cooky-the-view-from-the-shore-told-through-songlines-with-generosity-144065>, accessed 3 March 2021. |

| 9 | Oliver, Looky Looky Here Comes Cooky post-screening Q&A, op. cit. |

| 10 | Vika Mana, ‘TV Review: Looky Looky Here Comes Cooky Is Unapologetically Black’, screenhub, 20 August 2020,<https://www.screenhub.com.au/news-article/reviews/film/vika-mana/tv-review-looky-looky-here-comes-cooky-is-unapologetically-black-260938>, accessed 3 March 2021. Minor modification of punctuation. |

| 11 | Norman, op. cit. |