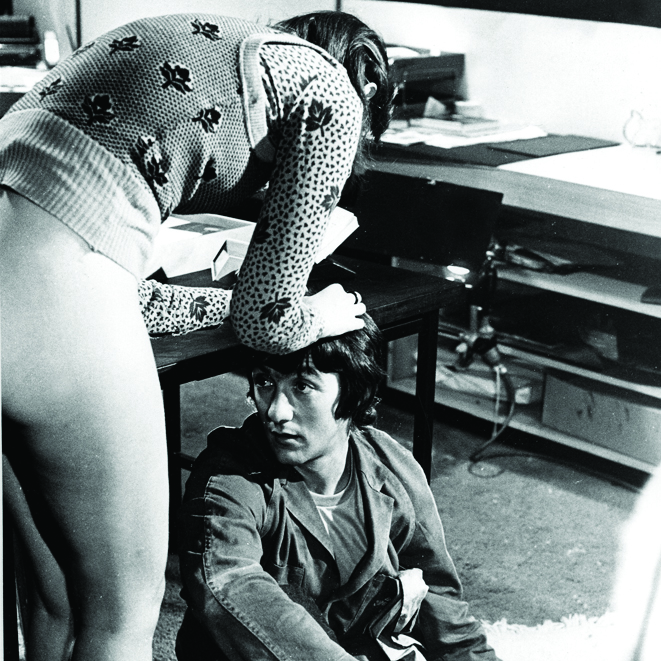

Tits, bums, sex, blood, gore and vomit – these were the staples of an Australian genre in the 1970s and 1980s that has come to be known as Ozploitation. In the documentary Not Quite Hollywood (2008), which opened this year’s Melbourne International Film Festival, director Mark Hartley has shone the spotlight on this forgotten era by gathering together those who were ‘in the trenches’ at the time, including directors, actors and producers, as well as a spirited detractor and one particularly famous and enthusiastic fan.

‘All that is left on the public record is the critical reaction at the time, which was not so good,’ says Hartley.

We’ve had a lot of analysis of our historic films, but that’s not the whole story of Australian film. These filmmakers had as much skill as our more heralded directors, but chose to work in a different genre. I hope the documentary captures the energy of times. They were all passionate about making these films.

Hartley grew up in the outer suburbs of Melbourne and never got to experience 1970s Australian genre cinema in the theatres or drive-ins. He discovered films such as The Man from Hong Kong (Brian Trenchard-Smith and Yu Wang, 1975), Patrick (Richard Franklin, 1978) and Snapshot (Simon Wincer, 1979) on late-night television. He tried to learn more about these films, but it was difficult to find much information.

In recent years Hartley had been researching and directing featurettes and feature-length documentaries for the local and international DVD releases of Australian films, including many Ozploitation titles. This led to him developing relationships with the cast and crew of these films, and in this way the seeds of Not Quite Hollywood were sown.

Hartley decided early on that he didn’t want to interview people with ‘no relationship to what they were talking about’. He only wanted to speak to those who had been involved in making the films, those with a genuine insight into them, or those of the next generation of filmmakers who had been directly influenced by the Ozploitation films.

To this end, Not Quite Hollywood features interviews with young Australian directors who have revived the genre film, namely Greg McLean (Wolf Creek, 2005) and Leigh Whannell and James Wan (Saw, 2004). Then there are the interviews with stalwarts of the Ozploitation scene, such as directors Brian Trenchard-Smith, Bruce Beresford and George Miller; producer Antony I. Ginnane; Australian actors Rebecca Gilling, Graeme Blundell, Sigrid Thornton, George Lazenby, Lynda Stoner and Jacki Weaver; American actors Dennis Hopper and Jamie-Lee Curtis; critics Phillip Adams and Bob Ellis; and director Quentin Tarantino, who wasn’t part of the era, but who is a huge fan of the genre.

‘There were about fifteen of us making films with our own voices, our own accents. Some think it was a time to be showing films aping British culture. But I knew some people wanted lowbrow.’

– Brian Trenchard-Smith (interviewee)

Brian Trenchard-Smith is a particular favourite of Tarantino’s. He directed such films as The Man from Hong Kong and Turkey Shoot (1982), and remembers the attitude of the times as ‘insane’. ‘The early to late seventies – wow, it was a blast,’ he says.

They were giddy, heady times. It was a glorious time to be part of the Australian film renaissance. We knew we were breaking new ground and breaking boundaries. We were creating film history … we were all learning on the job, teaching ourselves as we went. There were about fifteen of us making films with our own voices, our own accents. Some think it was a time to be showing films aping British culture. But I knew some people wanted lowbrow.

Hartley didn’t find it especially difficult to get figures such as Trenchard-Smith to be interviewed for Not Quite Hollywood. ‘All these people had fond memories of the films and it was a novelty [after thirty years] to talk about them. No one was embarrassed about the films.’

Hartley courted Tarantino by sending him a 100-page research document on the Ozploitation films. Soon afterwards, Tarantino’s assistant got back to Hartley and told him that the director had read the document from cover to cover, and would help him with whatever was needed to complete the project. The interview with Tarantino was the first one shot and ended up serving as a promo for the film.

Tarantino is an absolute delight in Not Quite Hollywood; he is clearly passionate about Australian films of that era. Hartley says the important consideration with Tarantino was ‘how much of him to use’.

I needed an overseas perspective. He saw all these films overseas and they were very influential on him. Tarantino points out that we shoot the bush or cars very differently to other parts of the world.

‘Nobody shoots a car the way Aussies do,’ enthuses Tarantino in Not Quite Hollywood, in characteristically over-the-top style. ‘They manage to shoot cars with this fetishistic lens that just makes you want to jerk off!’

Stunts were a big part of the film culture at the time, and no permits were ever sought, no police were ever informed, and safety officers were never thought of. Roger Ward knows this better than anyone, having worked as a stuntman and actor in Turkey Shoot, The Man from Hong Kong, Mad Max (George Miller, 1979), Mad Dog Morgan (Philippe Mora, 1976) and Stone (Sandy Harbutt, 1974).

Back then, it was just another film we were making. We hardly knew what we were doing. I helped out with the stunts. I drove cars, fell off cliffs and got burnt. I had a near miss with a cliff fall once. When I shot a gun the cliff edge broke away from the sound of the gun, and I fell. I was lucky.

He clearly recalls working on Stone, the violent bikie movie that had scenes with the Hells Angels.

I didn’t know anything about bikie culture, but I wasn’t going to be intimidated by these guys. I was amazed at how everyone, even all these gorgeous girls on set, loved them – dumb- and dirty-looking Hells Angels. To cut them down to size, I stepped up on to a balcony and said, ‘All Hells Angels are poofters!’ There was a fight. But the Hells Angels were always drunk and stoned, and falling off their bikes. What you see in the film is real; it’s not acting. One of them threw me in a ute and I ripped my shins. I was really angry and I was about to throw a punch but about twenty other Hells Angels stood around this guy … I hate violence, but I let it out in front of a camera. Violence on screen means you don’t have to take it out in a fight or on the street, or on a woman. I’m a gentle guy in real life!

Dennis Hopper came to Australia in 1976 to play the titular role in Mad Dog Morgan. Hartley managed to secure an interview with him for Not Quite Hollywood; pinning him down was a long and difficult process, though apparently not quite as difficult as dealing with him in 1976. Nobody had anything nice to say about him, including Ward.

I played a copper in Mad Dog Morgan. I didn’t like Dennis Hopper. He was an arrogant prick. He was on drugs pretty much most of the time. He invited everyone to a party in his room, but as everyone came to his door he took the girls in and slammed the door on the guys’ faces. I came on my own. I looked in the window and saw Dennis holding court. The guys just stood around outside. I said, ‘Let’s go in and get the girls,’ and they said, ‘No, no, he’s Dennis Hopper.’

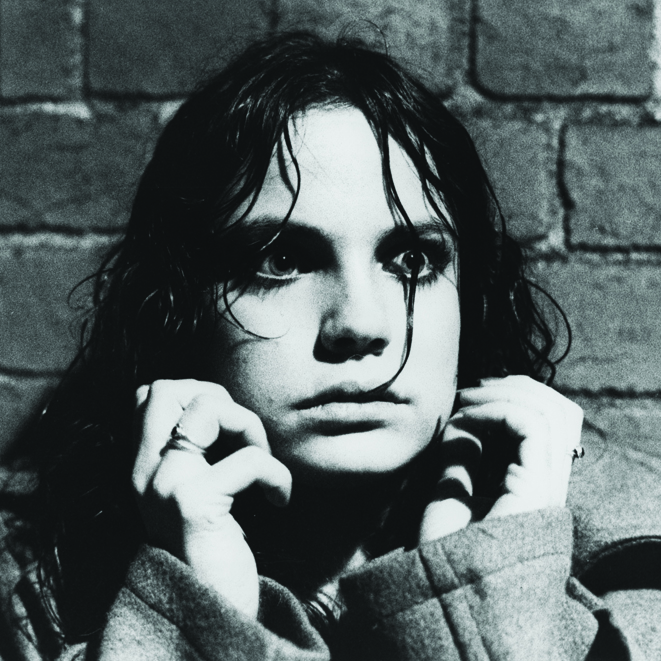

The serious historical films that were lauded by the critics at the time – the films that were the antithesis of what the Ozploitation films were about – cop some criticism in Not Quite Hollywood. Picnic at Hanging Rock (Peter Weir, 1975) comes in for a light-hearted serve; a photo of lead actress Anne Lambert is shown being vomited on, tying in with discussion of the vomit scene in The

Adventures of Barry McKenzie (Bruce Beresford, 1972). Hartley spoke to Lambert beforehand and told her how he would be referencing Picnic at Hanging Rock in his film. ‘We got Anne’s permission, and she gave me the photo for the vomit scene. She said, “You want a photo of me so you can vomit all over it? Oh, OK.”’

Trenchard-Smith concurs that at the time in Australia, there was a pervasive attitude that films had to be worthy and important, and that they should talk about social history and social problems.

But we made high camp movies with a nod to the Italian splatter movies. I find life enormously amusing. I tend to see the ironies of life. I put that into films, rather than making ‘serious, important films’. Although in Turkey Shoot the only serious point was that the camp commander’s name was Thatcher; [this was] making a point about the danger of right-wing fascism. We could see how far these people would go with power. The last eight years have proven that.

My films both celebrate and satirize life, with a wry perspective and subtext. As for major studios [wanting to back me], I was possibly a bit too wry. But Quentin Tarantino gets me. We felt we were part of a national enterprise, and we wanted to create a permanent industry. There was that esprit de corps, that camaraderie, even though we were competing for funds. But we helped each other out. We’d share the same actor in different films. There was a wish for your competitor’s success, as his success was your success in terms of Australian films.

The inclusion of the gruff Bob Ellis is a great counterpoint to all the enthusiasm shown by most of the other interviewees in Not Quite Hollywood. ‘Every film needs a villain, and he was happy to wear the black hat,’ says Hartley.

For the credits I wanted to find something [positive] that Bob said, but I couldn’t find anything! Bob was a critic, and Phillip [Adams] was important in getting the industry on its way. He fought against censorship, but then wanted Mad Max banned! Everyone was honest. No one pretended that [the films] were works of genius.

Exploitation or liberation?

One person’s liberation can be another’s exploitation. Hartley believes it’s important for an audience to cast aside a 2008 mindset when watching Not Quite Hollywood.

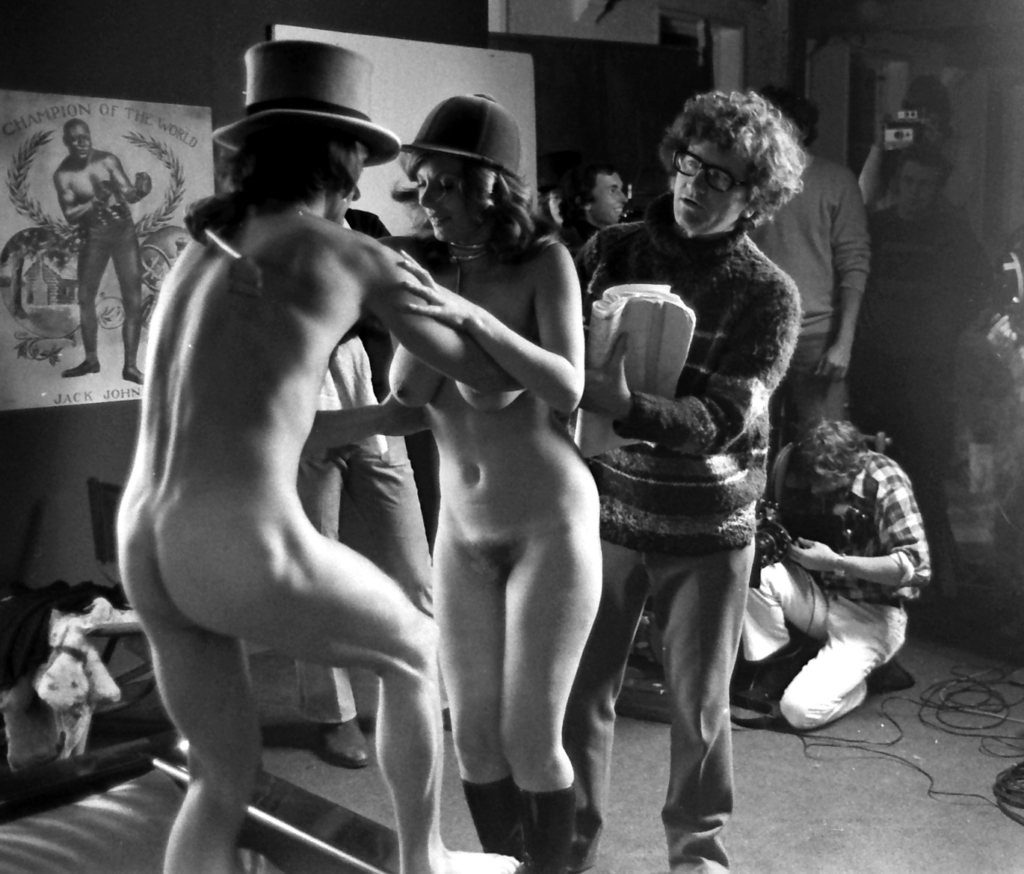

I didn’t want them to go in with hang-ups of exploitation. I tried to set it up through the prism of the seventies, so I tried to give an idea of the seventies at the start of the film, where exploitation was seen as liberation. People are making money from women getting their gear off, but many women thought of it as liberating.

‘I tried to give an idea of the seventies at the start of the film, where exploitation was seen as liberation. People are making money from women getting their gear off, but many women thought of it as liberating.’

– Mark Hartley

Film actress Deborah Gray, who was also a Playboy Playmate and starred in the risqué television series Number 96, says her strongest memories of the time are ones of hope and revolution.

It was a special time in history that we thought was going to be the start of bigger and better things. Society was changing all over the world, and this was reflected in the movies and music of the sixties and seventies.

There was peace, love and free spirit, where women were equal to men and our sexuality was explored. We wouldn’t be chattels to men. It was a time when people were breaking new ground. There was passion and energy. It was very fearless; people had a lot of courage. There was no calculation of how it would affect careers.

I wasn’t worried so much about how I was portrayed; I just wanted to be a part of it. People are much more conservative now than they were then. You’d go down to the beach in Australia and see topless women or nude bathers. We were young and it was a celebration of the body beautiful.

Gray said that she felt that the only time it became exploitative was when the films involved violence.

Around 1984 the film industry was becoming very violent, and that’s when I got out. I never had problems with nudity if it was done in an honest way, but when it was mixed up with violence it was sexualizing violence against women.

It should be noted that there were also women involved behind the scenes of some of the Ozploitation films. ‘I remember Pat Lovell and Sue Milliken, and Jill Billcock,’ says Trenchard-Smith.

More than a collection of stories

In the end, Hartley had about 150 hours of film footage, 150 hours of interviews and fifty hours of archive material, and it took him a month to watch it all. The most difficult thing for him when editing was achieving a balance between information and entertainment. He worked on the assumption that the audience would know nothing, so the film features background information before each section.

I’m happy with it. I don’t have to worry about it anymore. Lock off is incredibly liberating. People enjoy it, even people who don’t find any interest in this stuff. Seeing the film at MIFF hammered home to me that film plays to a young audience. When I showed a rough trailer of film footage [of the old films] to young kids, they couldn’t believe films were being made like that.

It always seemed like [the film] would never happen. It was an absolute delight going to work every day and working on a feature film. I suddenly got a work ethic! I know how lucky I was to make this film. I realized how much of an honour it was that I was the one telling this story. And [how the story was told] became more and more important … This is more than a collection of people telling stories.

MARK HARTLEY: ABOUT THE DIRECTOR

After graduating from the Swinburne School of Film & Television in 1990, Hartley worked in a variety of low-paying but ‘high-learning’ positions in the film industry, as well as directing and editing music videos.

He has directed over 150 film clips for artists including Powderfinger, You Am I, the Cruel Sea, the Living End and Sophie Monk. He has won two ARIAs and a Tui New Zealand Music Award, and has garnered an International MTV Award nomination and seven ARIA nominations.

Hartley has written and developed feature film projects, and since 2003 he has worked as a freelance director for DVD distributor Umbrella Entertainment, specifically on classic Australian cinema, which includes many of the Ozploitation films.

Not Quite Hollywood is Hartley’s first theatrical feature film.