There is plenty to say about Arrernte director Rachel Perkins’ Jasper Jones (2017), an adaption of Craig Silvey’s acclaimed 2009 novel of the same name. In 2014, the book was adapted for the stage by Kate Mulvany, playing to sold-out audiences in Perth that year[1]David Zampatti, ‘Jasper Jones a Standout’, The West Australian, 21 July 2014, <https://thewest.com.au/entertainment/arts-reviews/jasper-jones-a-standout-ng-ya-374365>, accessed 5 May 2017. and in both Sydney and Melbourne in 2016.[2]Susannah Guthrie, ‘Gripping Australian Novel Jasper Jones Gets Movie Treatment’, The New Daily, 16 December 2016, <http://thenewdaily.com.au/entertainment/movies/2016/12/16/jasper-jones-movie/>, accessed 5 May 2017. This year, the popular tale has been given the big-screen treatment.

The story is narrated by thirteen-year-old Charlie Bucktin – played in the film by Levi Miller – whose small Western Australian town panics over the mysterious disappearance of Laura Wishart (Nandalie Campbell Killick), the daughter of shire president Peter (Myles Pollard), during the summer of 1969. Fearful of another incident, Charlie’s parents, Ruth (Toni Collette) and Wes (Dan Wyllie), insist that he stay home, and the town enforces a curfew after sundown for children. This narrative element is reminiscent of segregation in Australia – bringing to mind Western Australia’s Aborigines Act 1905, which, among other things, prohibited Noongar people from being in Perth’s city centre after 6pm.[3]See ‘Impacts of Law Post 1905’, Kaartdijin Noongar – Noongar Knowledge website, South West Aboriginal Land & Sea Council, <https://www.noongarculture.org.au/impacts-of-law-post-1905/>, accessed 5 May 2017. These are the historical realities glanced at when a story told from a white viewpoint is translated for the screen by a black director.

Charlie first learns about Laura’s disappearance through a late-night tap on the window by her boyfriend, Jasper (Aaron McGrath), an older Aboriginal boy he has never, until now, met. Jasper implores him to come outside, where they soon enter a cloaked forest. I was not familiar with the forests of south-west Western Australia until I saw Jasper Jones, and neither was Perkins; she explains that they chose to shoot in the mill town of Pemberton, as Perth was too expensive.[4]See ‘Interview: Rachel Perkins and Craig Silvey (Jasper Jones)’, Cinema Australia, 28 February 2017, <https://cinemaaustralia.com.au/2017/02/28/interview-rachel-perkins-and-craig-silvey-jasper-jones/>, accessed 5 May 2017. These scenes are charged with an exuberance that diminishes when we leave the forest, suggesting that ‘place as a character’ cannot be elevated within the context of settler Australia’s disconnection with country.

Jasper then leads Charlie to a clearing, where Laura is hanging from a tree. He claims he has been set up for murder, and together they hide her body in a nearby pond.

Despite the film’s title, this story is not about Jasper … We are in Charlie’s world – his scholarly bedroom, the local library – and we follow his interactions with his parents and best friend, Vietnamese-Australian Jeffrey Lu.

Despite the film’s title, this story is not about Jasper – even though, during his moments on screen, newcomer actor McGrath, whom Perkins worked with before on Redfern Now,[5]Madman, Jasper Jones press kit, 2017, p. 8. shines. This story is Charlie’s, and we witness a very assured performance by young lead Miller, whose exciting upcoming appearances include the forthcoming A Wrinkle in Time (Ava DuVernay) alongside Oprah Winfrey and Reese Witherspoon. We are in Charlie’s world – his scholarly bedroom, the local library – and we follow his interactions with his parents and best friend, Vietnamese-Australian Jeffrey Lu (first-time actor Kevin Long), whose efforts in the cricket nets go unnoticed by the all-white team.

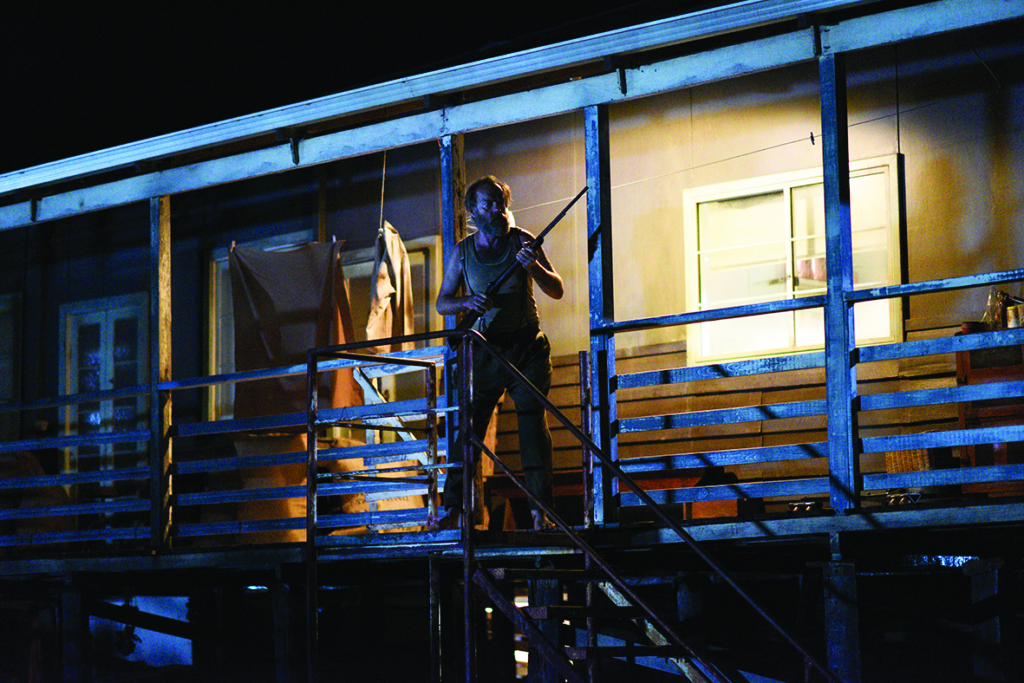

The young cast is bolstered by the experienced Collette, Wyllie and Hugo Weaving, whose collective brilliance brings the drama to a new level. In comparison to her counterpart in the novel, Collette’s Ruth is given more attention in the film script, co-written by Silvey and Shaun Grant, to explore the complexity under the surface of her marriage with Wes. Charlie’s father is more like him – an aspiring novelist, he often locks himself away in his room, working on his manuscript. He is also sympathetic towards Jasper, which may give us some hints as to Charlie’s emerging social consciousness. Weaving plays the crazed Mad Jack Lionel, whom Charlie – following Jasper’s suggestion – begins to believe is the real culprit behind Laura’s death.

Black and white stories

In Jasper Jones, the ‘crime mystery’ element is somewhat fuzzy but, arguably, we don’t watch the film for that. The social commentary is more interesting – the film sets out ‘not to assert that racism is bad and bigots are villains, but to investigate why and how such toxic principals [sic] persist within a culture’[6]ibid., p. 7. – yet this does not go very far, either. Even the dramatising of the race-hate directed at Jeffrey’s family, apart from one memorable moment, feels placid. With Jasper, we are given only vague details about his life that make the plot tick, but we know nothing of his heart. Jasper tells Charlie his mum passed away when he was very young; she was ‘not from here’. It is not known where the rest of his family is, his white father is an alcoholic, and Jasper is described as a fringe-dweller. What we do get is a holey plot: Why does Charlie help Jasper, whom he has never met? Why does Jasper come to his window? The connection between the boys is never explained – and we are left feeling as though narrative convenience has gotten in the way of plausibility.

The type of ‘outsider’ story laid out in Jasper Jones lends itself to old-fashioned storytelling; the nostalgic appeal pleases older audiences, who assure me that the era is well captured. A similar film set in 1960s Western Australia about the interracial friendship between a white boy and a black boy is the excellent September (2007), directed by white Australian Peter Carstairs. It centres on the changes to legislation in 1968 that saw Indigenous pastoral workers legally entitled to equal wages.[7]See ‘Reconciliation’, in ‘About Australia’, Australia.gov.au, 4 May 2015, <http://www.australia.gov.au/about-australia/australian-story/reconciliation>, accessed 5 May 2017. This impacts the relationship between the boys’ fathers: Paddy (Clarence John Ryan) and his dad have been working for Ed’s (Xavier Samuel) dad for a long time. The former, along with Paddy’s mum and younger siblings, live on the latter’s Wheatbelt property. Every day, Paddy’s and Ed’s mothers see each other from across their respective clotheslines. We watch the families cook, eat dinner, wash clothes; we learn of their differences and similarities. Both fathers are teaching the boys to drive. There is a structural power in place and this, too, starts to play out in Ed and Paddy’s relationship, swelling in the makeshift boxing ring the boys rig on the property using fencing supplies. September engagingly and emotively illustrates the social conditions for blackfellas prior to the 1970s, including segregation in town. We also see the guilt that afflicts Ed’s parents, who care about but do not act to change the set-up.

The model of friendship in September is one of growing up together, the sharing of space, the ability of both boys to honestly state their intentions and acknowledge their differences. Ed grows hopelessly fond of the new girl at school, and asks Paddy to venture out with him in the direction of her house in the quickly darkening countryside. When Ed makes this request, inviting Paddy to join him in entering ‘owned property’, it is with a misguided belief that their difference will not bring harm. But, of course, it does: when the girl’s father sees the boys, Ed runs, and it is Paddy who receives violence and is made to bear the full blame for Ed’s actions.

Another recent Australian film set in the late 1960s is the dynamic The Sapphires (2012), directed by Butchulla-Mununjali-Wakka Wakka filmmaker Wayne Blair, about a group of young Aboriginal women who become part of an entertainment cohort taken to Vietnam to perform for the troops. The Sapphires, based on the real-life experiences of Lois Peeler (nee Robinson) and Laurel Robinson,[8]Robin Usher, ‘Sparkle, in Any Colour’, The Age, 15 November 2004, <http://www.theage.com.au/articles/2004/11/12/1100227566726.html>, accessed 11 May 2017. illustrates different dimensions of black life in Australia at the time, one year after the 1967 referendum. The young women are from the Cummeragunja mission except for Kay (Shari Sebbens), who, deemed ‘white enough’, was raised in the city – the result of devastating government policy affecting the lives and bodies of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people – harming how she identifies with her community and how her community identifies with her. ‘So you black now or are you white?’ the oldest of the group, Gail (Deborah Mailman), goads Kay during a heated discussion.

Unlike The Sapphires and September, Jasper Jones doesn’t show us the broader context of this pivotal period in Australian history, nor do we glean it from the interpersonal tension between Jasper and Charlie. Instead, it attempts to explain the space between the boys through the use of heavy dialogue. In one of the very few lines he gets, Jasper says, ‘You’re an outsider, like me’; here, he is referring to Charlie’s interests in reading and writing – that is, he is not engaged with sport like the rest of the town. Early on in the film, Jasper asks Charlie, ‘They’re gonna say it’s me [who killed Laura …] Who did you blame first?’ Jasper subsequently says, ‘I can’t tell the truth. This is Corrigan; no-one would believe me’ – hinting at the townsfolk’s destructive attitude towards Aboriginal people. Paralleling this, the white Australian ‘give a go’ ethos is drawn out on the cricket pitch, a place of ‘inclusion’ – Jeffrey gets ‘a go’ and he ‘goes’ wonderfully, hitting sixes and fours. Charlie likewise gives Jasper ‘a go’ by suspending his suspicion: walking into the forest, Charlie says in voiceover, ‘People in town say he’s dangerous. But I’ve always wondered what he’s really like.’

Perkins and the power of perspective

In 1992, Perkins founded Blackfella Films, and since then has been at the forefront of Indigenous representation on screen. Her successes include the acclaimed television drama Redfern Now; the ABC telemovie Mabo (2012), about the life of land rights instigator Eddie Mabo; and the important documentary Black Panther Woman (2014), about Marlene Cummins, her life of addiction and her role in the Australian Black Panther party.[9]Blackfella Films also produced the recent controversial docu-reality series First Contact. Perkins was drawn to the Jasper Jones project because of her love of the novel. In a Screen-Space interview, Perkins describes her focus when making films:

Having some underlying meaning or providing some commentary on how we can improve the world has always been a part of my work. It might sound a bit naïve, but I think films can change hearts and minds. This film is about a young guy who, when exposed to the world that the character Jasper Jones inhabits, displays a lovely compassion.[10]Rachel Perkins, quoted in Simon Foster, ‘Jasper Jones: The Rachel Perkins Interview’, Screen-Space, 1 March 2017, <http://screen-space.squarespace.com/features/2017/3/1/jasper-jones-the-rachel-perkins-interview.html>, accessed 5 May 2017.

Understanding who connects with a story is important when translating a book for the screen. The filmmakers recognised that the book was very popular with young readers; it resonated with them, as well as with a senior audience.[11]David O’Connell, ‘Rachel Perkins: A Novel Approach’, X-Press Magazine, 27 February 2017, <http://xpressmag.com.au/rachel-perkins-a-novel-approach/>, accessed 5 May 2017. Perkins trusted first-time screenwriter Silvey to co-write the script with Grant, and she worked closely with Silvey on set as well; his discussions with the cast proved helpful in gaining insights into their characters.[12]Foster, op. cit. In particular, of Charlie’s coming-of-age journey, Silvey has previously said:

[O]ne of my primary areas of consideration was the sloughing of innocence that is growing up, that moment where the bubble is burst and you’re suddenly exposed to the real truth of things and the blind trust of childhood dissolves.[13]Craig Silvey, ‘Craig Silvey Discusses Writing Jasper Jones’, Allen & Unwin website, <https://www.allenandunwin.com/writers-on-writing/craig-silvey-discusses-writing-jasper-jones>, accessed 5 May 2017.

We are encouraged to believe that it is curiosity that drives Charlie out of his bedroom and on the hunt to help clear Jasper’s name. But how does Charlie see Jasper? We don’t see. Curiosity can be a trap; Charlie’s wide open eyes are also blind. His limited view of Jasper is consistent with the film’s lack of political rigour as a whole. Charlie’s seemingly innocuous (but actually problematic) exoticisation of Jasper – of ‘wonder[ing] what he’s really like’ – blends with his childlike romanticisation of events, glossing over the deeper political realities plaguing Jasper’s life. At the story’s end, Charlie’s life goes back to normal, curiosity sated, knowledge gained, privilege conserved, while Jasper has to continue living with ongoing dispossession and racial oppression.

We are encouraged to believe that it is curiosity that drives Charlie out of his bedroom and on the hunt to help clear Jasper’s name. But how does Charlie see Jasper? … His limited view of Jasper is consistent with the film’s lack of political rigour as a whole.

As our country continues to promote stories that deal with large and complex issues such as racism, class disparity, sexism and abuse in neat and superficial ways in order to create ‘entertaining’, ‘heartfelt’ experiences for a mainstream audience, we are left with a blurred image of our national identity – one that sustains itself, in a cyclical, self-feeding loop, and remains the same. It may be others’ view that films about the past do not need to fuse with commentary of the present, but a constant inspection must be in place on how, why and where we tell our stories.

http://www.jasperjonesfilm.com

Endnotes

| 1 | David Zampatti, ‘Jasper Jones a Standout’, The West Australian, 21 July 2014, <https://thewest.com.au/entertainment/arts-reviews/jasper-jones-a-standout-ng-ya-374365>, accessed 5 May 2017. |

|---|---|

| 2 | Susannah Guthrie, ‘Gripping Australian Novel Jasper Jones Gets Movie Treatment’, The New Daily, 16 December 2016, <http://thenewdaily.com.au/entertainment/movies/2016/12/16/jasper-jones-movie/>, accessed 5 May 2017. |

| 3 | See ‘Impacts of Law Post 1905’, Kaartdijin Noongar – Noongar Knowledge website, South West Aboriginal Land & Sea Council, <https://www.noongarculture.org.au/impacts-of-law-post-1905/>, accessed 5 May 2017. |

| 4 | See ‘Interview: Rachel Perkins and Craig Silvey (Jasper Jones)’, Cinema Australia, 28 February 2017, <https://cinemaaustralia.com.au/2017/02/28/interview-rachel-perkins-and-craig-silvey-jasper-jones/>, accessed 5 May 2017. |

| 5 | Madman, Jasper Jones press kit, 2017, p. 8. |

| 6 | ibid., p. 7. |

| 7 | See ‘Reconciliation’, in ‘About Australia’, Australia.gov.au, 4 May 2015, <http://www.australia.gov.au/about-australia/australian-story/reconciliation>, accessed 5 May 2017. |

| 8 | Robin Usher, ‘Sparkle, in Any Colour’, The Age, 15 November 2004, <http://www.theage.com.au/articles/2004/11/12/1100227566726.html>, accessed 11 May 2017. |

| 9 | Blackfella Films also produced the recent controversial docu-reality series First Contact. |

| 10 | Rachel Perkins, quoted in Simon Foster, ‘Jasper Jones: The Rachel Perkins Interview’, Screen-Space, 1 March 2017, <http://screen-space.squarespace.com/features/2017/3/1/jasper-jones-the-rachel-perkins-interview.html>, accessed 5 May 2017. |

| 11 | David O’Connell, ‘Rachel Perkins: A Novel Approach’, X-Press Magazine, 27 February 2017, <http://xpressmag.com.au/rachel-perkins-a-novel-approach/>, accessed 5 May 2017. |

| 12 | Foster, op. cit. |

| 13 | Craig Silvey, ‘Craig Silvey Discusses Writing Jasper Jones’, Allen & Unwin website, <https://www.allenandunwin.com/writers-on-writing/craig-silvey-discusses-writing-jasper-jones>, accessed 5 May 2017. |