An uncompromising, unconventional and controversial film at the time of its release, The Devil’s Playground was the first feature by Fred Schepisi, who wrote, directed and produced it, and went on to become a pivotal figure in the so-called renaissance of the Australian film industry in the 1970s and 1980s – an era which also spawned Tim Burstall, Peter Weir, Phillip Noyce, Bruce Beresford and Gillian Armstrong. The film is set in a Catholic seminary for adolescent boys who are studying to enter the religious order of teaching brothers. It is Victoria in the autumn of 1953.

The Devil’s Playground explores themes surrounding puberty and burgeoning sexual desires amongst the pupils, as well as sexual repression and religious fanaticism amongst the teaching brothers – subject matter that was groundbreaking, not only for Australian films, but for international films as well. A critical and commercial success at home, The Devil’s Playground won Best Film, Best Director, Best Actor (shared by Simon Burke and Nick Tate), Best Cinematography, Best Original Screenplay and the Jury Prize at the 1976 Australian Film Institute Awards.

Despite this success, The Devil’s Playground now appears to be almost a forgotten Australian film. In the last few years a growing number of great Australian films from the 1970s and 1980s have been re-released on DVD, including Newsfront (Phillip Noyce, 1978), Picnic at Hanging Rock (Peter Weir, 1975), Sunday Too Far Away (Ken Hannam, 1975), and Gallipoli (Peter Weir, 1981). But The Devil’s Playground still awaits an official re-release on DVD. The apparent lack of recognition for The Devil’s Playground could be due to its subject matter of sexual repression within a Catholic seminary for boys in the 1950s. Its themes may not resonate with the same power in 2006 as they did in 1976: certainly, the public has become accustomed to hearing about sexual abuse in the Catholic Church in the intervening thirty years. Nevertheless, The Devil’s Playground remains a vitally important Australian film that deserves to be re-examined and re-appraised in 2006.

The Background to the Film

The Devil’s Playground cost around $300,000 to produce and was shot in six-and-a half weeks at Werribee Park mansion in Chirnside[1]Sue Mathews, ‘35mm Dreams: Conversations with Five Directors About The Australian Revival’, Penguin, Melbourne, 1984. p.31. (which housed a seminary from 1923 to 1973). The film earned back its production cost in Australia with a healthy run of eight months in Melbourne and Sydney, which vindicated Schepisi’s decision to distribute the film as a commercial venture rather than an art-house release. Schepisi has also acknowledged that the AFI awards helped the success of the film in Australia. As he explains, ‘There is no question that awards and festivals helped Devil’s Playground locally. In fact, I am sure they were responsible for it being released.’[2]David Roe and Scott Murray, ‘Production Report’, Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith, Cinema Papers, Issue 15, January 1978, p.224. Unfortunately, The Devil’s Playground was a commercial failure overseas. Says Schepisi, ‘I thought we would get three quarters of our money back here and end up with double our money back overseas. It turned out that we got all our money back here and nothing from overseas.’[3]ibid.

Fred Schepisi was thirty-six when he made The Devil’s Playground, with a long and varied career already behind him. Born in Melbourne in 1939, Schepisi initially pursued a career path as a Catholic priest, entering a Roman Catholic boarding school at the age of eight. However, by fifteen Schepisi had left the seminary to follow a career in advertising.[4]Peter Malone, Myth and Meaning: Australian Film Directors in Their Own Words, Currency Press, NSW, 2001, p.110. Working in advertising allowed him to acquire and develop business skills that would prove invaluable in his later career as a filmmaker.

When television arrived in Australia in 1956, Schepisi moved on to television commercials and documentaries, establishing a reputation for innovative and experimental camera techniques that he would later incorporate into his films, including The Devil’s Playground. At twenty-four, he took a job at Cinesound in Victoria. (Cinesound was one of Australia’s most productive feature film studios back in the 1930s. From the 1940s through to the 1960s, it was best known for its movie-theatre newsreels.) In February 1966, Schepisi and two colleagues purchased a studio production company named the Film House, which was to operate for the next thirty-one years. The Film House gave Schepisi a base from which to move into film direction, as well as a ready-made group of skilled technical people that he could use as a film crew. It also served as a creative outlet for a new generation of up-and-coming Australian filmmakers who, along with Schepisi, came to prominence in the 1970s and 1980s.

Schepisi’s first foray into filmmaking was The Priest, a half-hour short contained in Libido (1973). A selection of four short films, Libido paired a quartet of up-and-coming Australian directors (Fred Schepisi, Tim Burstall, John B. Murray and David Baker) with scripts by four of Australia’s best writers (David Williamson, Thomas Keneally, Hal Porter and Craig McGregor). The Priest, along with the other stories in Libido (The Husband, The Child and The Family Man) explored themes involving carnal desires, adultery, jealous fantasies and the notion of childhood innocence. Schepisi chose a story by Thomas Keneally for his section of Libido. Interviewed some years later, he discussed his collaboration with Keneally, ‘Tom’s script had come in and I just jumped on it. I just muscled my way into that because I wanted Tom to read Devil’s Playground. He did and was incredibly kind about it.’[5]ibid., p.112. Filmed in 1972 in a mere six days, The Priest explores the moral and spiritual conflicts of a Catholic priest and a nun who are in love, foreshadowing themes that were to be examined in more detail in The Devil’s Playground. The Priest also starred Arthur Dignam, who gives a powerful, believable and sympathetic portrayal of the title character. (Dignam was to feature prominently in The Devil’s Playground, again playing a repressed priest).

But The Devil’s Playground was the film that really began Fred Schepisi’s distinguished film career.Reviewing the film in 1976, Pauline Kael called Schepisi, ‘a great filmmaker’ and declared, ‘I don’t really see how this movie could be much better.’ Kael went on the describe Schepisi as ‘the odd man out – the artist in the Australian film renaissance, which is otherwise a celebration of the work of intelligent, slightly impersonal craftsmen’.[6]Quoted in Ryan Gilbey, ‘Unmade Freds’, Sight and Sound, Vol. 12, No. 1, January 2002, p.12.

Reviewing The Devil’s Playground in 1976, Pauline Kael called Fred Schepisi, ‘a great filmmaker’ and declared, ‘I don’t really see how this movie could be much better.’

However, Schepisi had to endure various trials and tribulations in order to get The Devil’s Playground (with its controversial subject matter) financed and distributed in Australia. Interviewed after the release of the film, he spoke about these difficulties:

It took me five years. I got half the money from the government and the other half of the money was mine, and my friends’. When I finished the film, I immediately had to go back to making commercials – which was the worst thing I ever did in my life – just to get the money to keep paying for the film. And then nobody wanted to distribute it. Nobody believed in it at all. So I had to distribute it myself.[7]‘Dialogue on Film’, American Film, Vol 12, No. 9, July/August 1987, p.11.

This hands-on approach to distribution involved Schepisi trudging from city to city, paying for everything from promotion to the hiring of cinemas. As he explained some years later, ‘It was very tough, but I insisted it was a commercial picture and made sure it was treated that way.’[8]Mathews, op. cit., p.35.

A Daring and Unusual Film

The Devil’s Playground is an unusual film in that it doesn’t have a conventional narrative structure with a beginning, middle and end. An authentic and faithful representation of a particular time and place, it is a study of what many Catholic boys would have experienced at similar seminaries in Australia during the 1950s. A moody, contemplative, almost dreamlike meditation on puberty and sexual repression, The Devil’s Playground can be viewed as a series of vignettes depicting different aspects of daily life within the restrictive confines of a Catholic seminary.

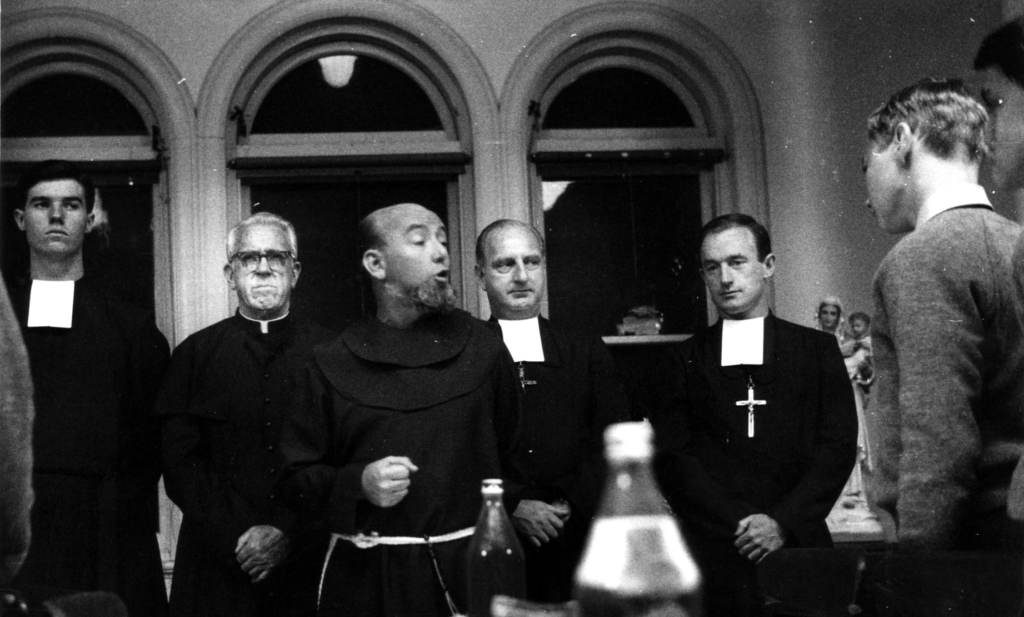

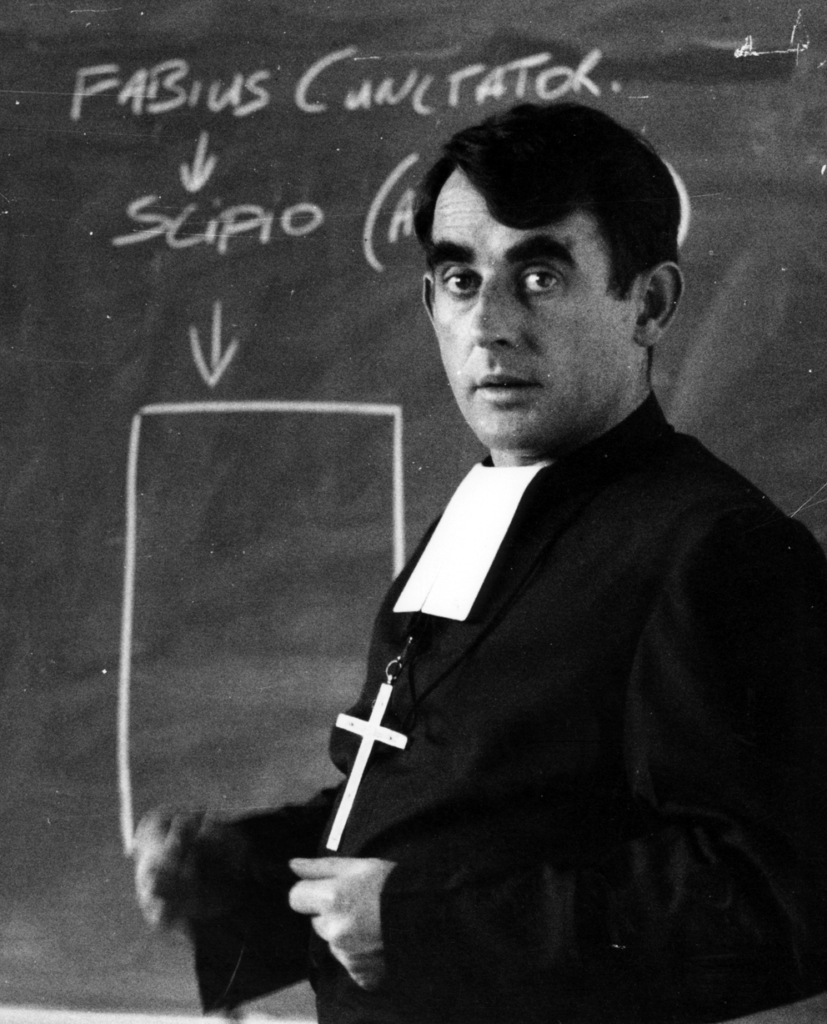

The Devil’s Playground is a finely detailed study of both the pupils and the teachers at the seminary. Central to The Devil’s Playground is 13-year-old Tom Allen (Simon Burke). The film explores young Tom’s awkward path through puberty from within the sexually repressive environment of the seminary. Tom’s character also provides an element of normality, which serves as a counterpoint to other characters in the film who have a range of perverse beliefs. Chief amongst these is Brother Francine (Arthur Dignam), who is a religious fanatic. Brother Francine is contrasted with the gregarious Brother Victor (Nick Tate), who likes to smoke, drink and watch football. There is also the elderly Brother Sebastian (Charles McCallum), who no longer appears to believe in the faith. Brother Sebastian takes Tom under his wing and encourages him to make up his own mind about whether or not he should follow the religious path. In addition, there is Fitz (John Diedrich), an older pupil who acts as both friend and mentor to Tom.

For a younger audience in 2006, the draconian world of the Catholic seminary depicted in the film may seem hard to believe. However, Schepisi insists that he actually toned down the repressive nature of school:

Believe me, I held back. See I went to Assumption [Catholic College] and was there for so long before I went to school that I was kind of horrified by what they were doing, what was happening in that school. You’ve got to remember that the majority of these kids were going through puberty but it’s all been covered up, so that makes it twenty times as bad.[9]Malone, op. cit., p.114-5.

Schepisi also maintains:

I knew if I went as far as I should go, everyone would go, ‘Oh come on, that’s not possible.’ Nobody would believe it. So I deliberately pulled back on all sorts of things, so the impression was shocking enough or jangling enough without going the whole hog.[10]ibid., p.114.

Acknowledging that the film is partly based on his own experiences, Schepisi asserts:

It’s semi-autobiographical. When I was thirteen I decided I wanted to enter the monastery, and I think my parents made the wisest decision and let me do it. I left a year and a half later, by which time I had got it out of my system.[11]Mathews, op. cit., p.36.

What made him leave the monastery was the authoritarian environment: ‘They had the kind of ridiculous rules and regulations you find in any community or group that has nothing to do with the realities of existence. They destroy the things they should be promoting.’[12]Judy Stone, op. cit., p.27.

Schepisi has also revealed that, to some extent, the brothers depicted in The Devil’s Playground are based on people from his own Catholic background:

The brothers are combinations of various people and some are made up. Once when I was about nine I was in the infirmary of my Catholic primary school, which happened to be right next to the brothers’ billiard room, so I could hear some of the conversations, and once I stayed back for a few days at the end of term; they were more relaxed in these circumstances, so I briefly got inside their world. The film was made up of what I thought it would be like, and what I thought I would become.[13]Mathews, op. cit., p.36.

One criticism that could be made of The Devil’s Playground is that the depiction of Brother Francine is so extreme he comes close to caricature at times. However, Schepisi asserts:

I can tell you that the Arthur Dignam character is a mere shadow of a couple of the people I experienced. When the film came out, people used to ring me up and write me letters and burn T-shirts and send them to me. Almost any Catholic boy who has been to boarding school will say of that character: ‘That was Brother —’. There was one in every school, and they’d say to me, ‘Oh, you were kind to him.’[14]ibid., p.37.

A Haunted ‘Playground’

With The Devil’s Playground Schepisi has created an authentic and understated portrayal of a particular Australian Catholic childhood of the 1950s. Integral to this sense of time and place is the look and sound of the film. This is apparent from the opening credits, with Bruce Smeaton’s lush musical score conjuring up a feeling of innocence, beauty, even nostalgia. Ian Baker’s striking cinematography gives the film a documentary feel, his camera acting as an observer to the various intertwining episodes or vignettes between the boys and the brothers, while creating a moody, dream-like atmosphere.

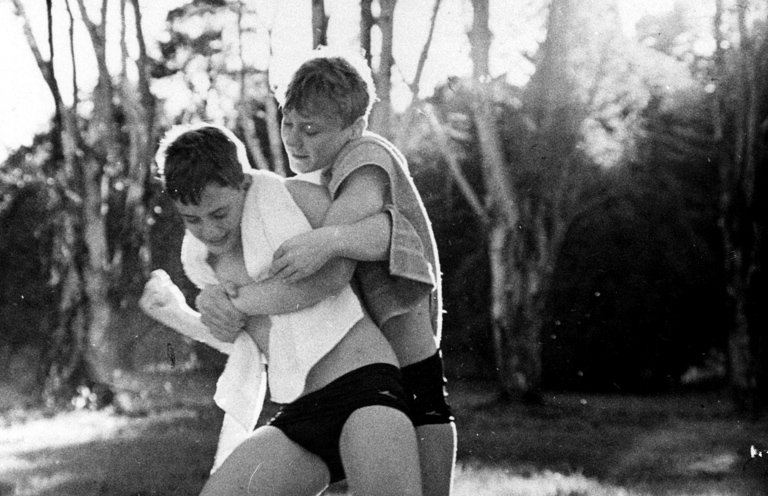

The opening scene of The Devil’s Playground sets the tone for the rest of the film. It is late afternoon and the sun is slowly sinking as it flickers between the trees. There is a nip in the air. The camera glides languidly along the surface of a river, observing the boys as they frolic in the cold water. The beauty of the outdoor scenes is contrasted strikingly with the sterility of the monolithic and imposing structure of the seminary, with its cold chambers and dark hallways.

The protagonist Tom Allen represents youthful innocence as he struggles with the onset of puberty (he is constantly ribbed by the other boys for his embarrassing habit of bed-wetting) from within the confines of the Catholic seminary. Tom has not yet been indoctrinated into the brotherhood or tainted by the repressive lifestyle. He is therefore open to a variety of influences, both good and bad. He even has a brief flirtation outside the seminary with Lynette (Danee Lindsay), a girl from the nearby Christian Fellowship Association. The normality of Tom’s character is contrasted with other emotionally and sexually repressed characters in the seminary.

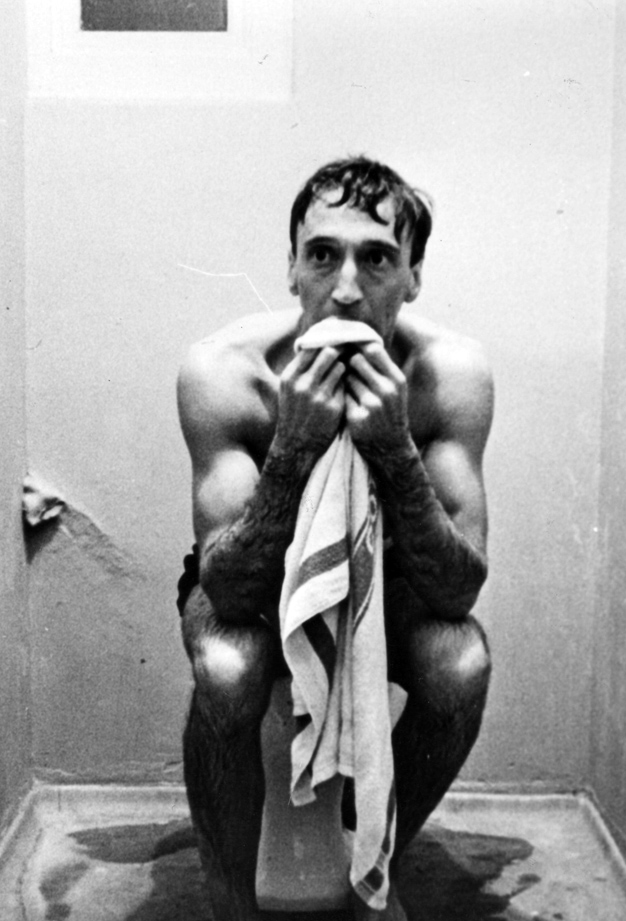

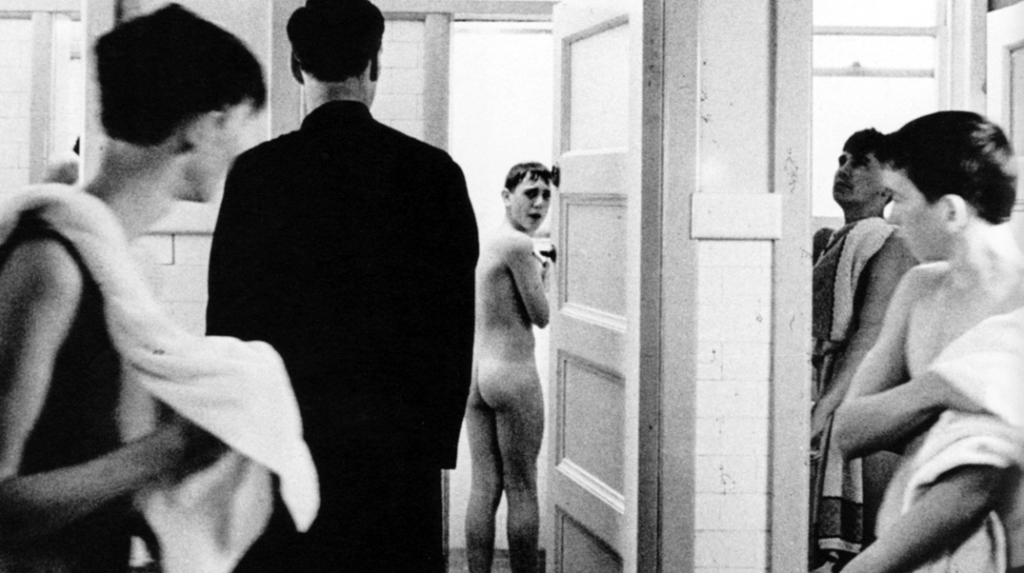

The Devil’s Playground also contains finely detailed characterizations of several teaching brothers, all of whom are linked by their adherence to the doctrines of the Catholic Church, but deal with the repressive lifestyle of the seminary in different ways. Brother Francine’s dogmatic, disturbing and pitiful religious fanaticism is demonstrated early in the film. As the boys shower after swimming, Tom takes off his bathers, which is against the regulations. Brother Francine angrily chastises him:

You’re disgusting. Exposing yourself. Where is your modesty? If you want to be a little brother of Mary, you must learn that your body is your worst enemy, Allen. The eyes are the windows of the soul and must be protected. You must be on guard to all your senses at all times. You’re preparing for the Brotherhood. That requires you to take stringent vows. Poverty, obedience, chastity. Hear that Allen, chastity. Practice self-denial, self-examination, self-discipline, so you may be worthy of the call to become one of God’s chosen few.

However, it is revealed later in the film that Brother Francine doesn’t practice what he preaches. On a rare trip outside the walls of the seminary to a public swimming pool, he sits in the male change rooms surrounded by naked men, his awkwardness and self-consciousness painfully obvious. What follows is a beautifully constructed sequence in which Brother Francine’s repressed sexuality is emphasized by a series of shots shown from his perspective as he stares at women getting out of the pool and getting changed, momentarily catching fleeting glimpses of female flesh. The sequence ends with Brother Francine seeking sanctuary in a toilet cubicle, shaking and frightened. In a later scene, Brother Francine has an erotic dream where he envisions himself and a couple of young women swimming naked underwater in a bright blue swimming pool.

In contrast to Brother Francine, Brother Victor is likeable, outgoing and good-natured. He also enjoys a smoke and drink, as well as watching football. Unlike Brother Francine, who is in denial about his desires, Brother Victor exhibits self-awareness, openly questioning the artifice and unreality of the constraints that the religious life imposes on him. This is demonstrated in the scene in which Brother Victor gazes out of a window and surveys the activities taking place in the grounds outside, reflecting on, ‘the devil’s playground. I wish he would play in someone else’s ground and leave me alone … It gets us all in various ways. It’s not natural. It’s not bloody natural.’

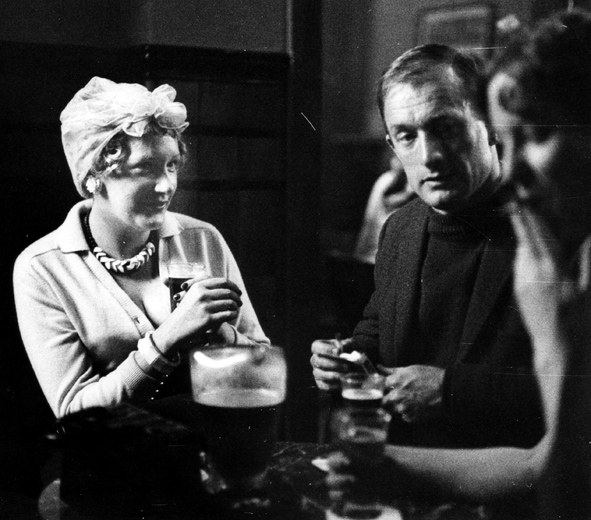

In another revealing scene, Brother Victor is drinking in a bar after the football game with Brother James (Peter Cox) when he spies two women sitting nearby. Summing the courage to approach them, he sits down nervously to join them for a drink. A little later, the film cuts to a bewildered and flustered Brother Victor as he returns to the car, where he exclaims, ‘God Jim, they were serious. They nearly had me.’ While we are not shown what actually happened, it can be assumed that the women wanted to get a little too friendly for Brother Victor’s liking. It is clear from this scene that for all his misgivings about the religious life he has chosen, Brother Victor is institutionalized like the other brothers. He seeks the solace and safety of the seminary when life outside the walls becomes too difficult for him to handle. Although Brother Victor questions his life in the seminary, and is able to clearly articulate his dissatisfaction with it, he is ultimately committed to the brotherhood. This commitment is reinforced in another scene when he tells Father Marshall (Tom Keneally), ‘I belong here. Part of a community.’

Another important character is the older pupil Fitz, who acts as a mentor to the impressionable Tom. Fitz is a voice of reason and sanity amidst the religious dogma being spouted by others. He warns Tom against becoming involved with the more fanatical boys in the seminary, like Turner (Michael David) and his group of sadomasochists. Later in the film, Fitz disappears from the seminary, presumably having been expelled (told to ‘pick up his pen’) because he is seen as an unsavory influence on Tom.

Possibly the most profound influence on Tom is the elderly Brother Sebastian. An intriguing character, it appears that Brother Sebastian no longer believes in the Catholic faith. His doubts are revealed in a beautifully acted scene in which the brothers play snooker and talk candidly about the challenges that the young pupils face as they strive to acquire the self-discipline needed to become a member of the religious order of teaching brothers. Unexpectedly, Brother Sebastian speaks up: ‘What if God isn’t there? We’ll hate ourselves then, won’t we?’ There is also a crucial scene near the end of the film between Brother Sebastian and Tom, in which the elderly priest encourages Tom to make up his own mind about religion, counselling him: ‘If the life here troubles you too much, give it up. A lifetime’s a long time to be unhappy, Tom.’ Brother Sebastian’s remarks are perhaps tinged with regret stemming from a feeling that his own life has been wasted – being able to save Tom from a similar fate may serve as a source of comfort to him as his life draws to a close.

The ending of The Devil’s Playground is open to interpretation. Tom, having been prevented from receiving and reading letters from Lynette, contemplates running away from the seminary. Standing by the roadside, he is picked up by Brother Victor and Brother James on their way to the football. Tom begins to smile as the two priests joke with him. The camera freezes on Tom for several moments as he gazes reflectively out of the car window. His future remains uncertain. Will he return to the seminary or make a definitive break for freedom?

Where is the DVD?

It is gratifying that many of the great Australian films of the 1970s and 1980s are being restored and preserved for future generations. In 2000, following the restoration of Newsfront (Phillip Noyce, 1978) for a special edition DVD by Canberra’s National Film and Sound Archive, an ambitious program to save dozens more Australian films of the 1970s and 1980s in danger of major deterioration was launched by the archive. The Devil’s Playground was included in an initial list of 51 Australian films from the above period to be restored. Here’s hoping that there will be an official remastered DVD release of The Devil’s Playground, soon. Recently, Simon Burke, who was thirteen when he played Tom Allen, remarked that he was looking forward to seeing the remastered film, while also expressing shock that he is now old enough to have appeared in a film that is in need of restoration.[15]Quoted in ‘Restoring Australia’s Film Soul’, Steve Dow, at http://www.stevedow.com.au/Article/article.asp?id=232

What’s next for Fred Schepisi? He has recently had a couple of serious health scares, being treated in 2005 for prostate cancer, as well as being diagnosed a few years ago with advanced lymphoma of the spine. However, Schepisi continues to work on a number of projects that interest him. He has recently completed Empire Falls, a series based on an adaptation of Richard Russo’s Pulitzer-Prize-winning novel, which was made for the American HBO network. (The series won two Golden Globes and an Emmy, and was screened in Australia on Pay TV). Schepisi’s current project is The Last Man, which is his first Australian production in eighteen years. The Last Man is based on a book by Graham Brammer, Uncertain Future, which tells the story of five SAS men in the final days of the Vietnam War. However, Schepisi still has to find half of the $27 million required to complete the film.[16]Caroline Baum, ‘Fred Bare’, The Age, Good Weekend Magazine, 22 April 2006.

In the thirty years since The Devil’s Playground was released in 1976, Fred Schepisi has gone on to have a long career as a highly regarded filmmaker. The Devil’s Playground, however, is quite possibly his best film, and remains a remarkable achievement for a first-time feature director. Moreover, Schepisi should be given great credit for being courageous enough to make a film that involves such contentious and complex subject matter. A beautifully crafted film, the greatness of The Devil’s Playground lies in its understated attention to detail, both visually and aurally, which accurately evokes a particular time and place, as well as the meticulously developed and non-judgemental characterizations of the adolescent boys and the teaching brothers. Here’s hoping the DVD release is not far away.

Endnotes

| 1 | Sue Mathews, ‘35mm Dreams: Conversations with Five Directors About The Australian Revival’, Penguin, Melbourne, 1984. p.31. |

|---|---|

| 2 | David Roe and Scott Murray, ‘Production Report’, Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith, Cinema Papers, Issue 15, January 1978, p.224. |

| 3 | ibid. |

| 4 | Peter Malone, Myth and Meaning: Australian Film Directors in Their Own Words, Currency Press, NSW, 2001, p.110. |

| 5 | ibid., p.112. |

| 6 | Quoted in Ryan Gilbey, ‘Unmade Freds’, Sight and Sound, Vol. 12, No. 1, January 2002, p.12. |

| 7 | ‘Dialogue on Film’, American Film, Vol 12, No. 9, July/August 1987, p.11. |

| 8 | Mathews, op. cit., p.35. |

| 9 | Malone, op. cit., p.114-5. |

| 10 | ibid., p.114. |

| 11 | Mathews, op. cit., p.36. |

| 12 | Judy Stone, op. cit., p.27. |

| 13 | Mathews, op. cit., p.36. |

| 14 | ibid., p.37. |

| 15 | Quoted in ‘Restoring Australia’s Film Soul’, Steve Dow, at http://www.stevedow.com.au/Article/article.asp?id=232 |

| 16 | Caroline Baum, ‘Fred Bare’, The Age, Good Weekend Magazine, 22 April 2006. |