Like life itself, as the screenplay of The Babadook (Jennifer Kent, 2014) reminds us several times, motherhood can be treacherous. What if your child is disobedient or doesn’t listen? What if your child is unstable or, worse, unlikeable? What if he doesn’t love you enough? Or loves you too much? One thing’s for sure: there’s no escape. By the third act of Kent’s Gothic mood piece, Amelia (Essie Davis) and her six-year-old son, Samuel (Noah Wiseman), are trapped together in a nightmare, with no-one to turn to except each other. ‘Hell is other people,’ as Jean-Paul Sartre famously proposed.[1]Jean-Paul Sartre, No Exit, 1944.

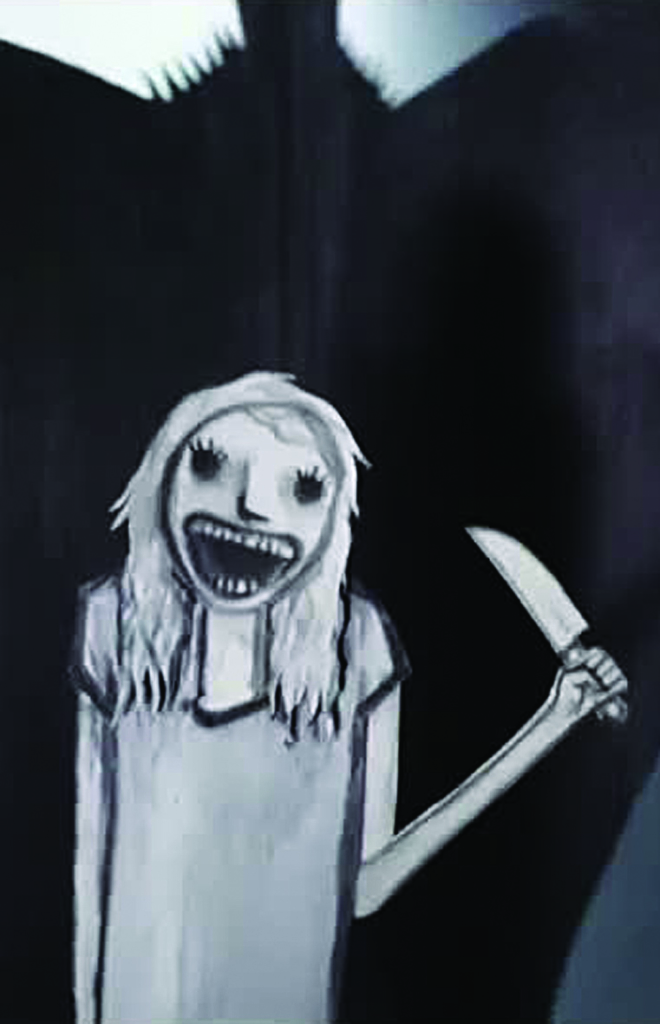

Except that this hell also contains a monster called the Babadook, who seems to have sprung fully formed from a creepy pop-up picture book in Samuel’s bookshelf – the ‘word made flesh’. Or did the Babadook create the book and then inhabit it? On the other hand, he may be a figment of Amelia’s or her son’s imagination. What is clear is that the Babadook is in some sense the product of tragedy, a manifestation of the grief that was born, as was Samuel, on the night Amelia’s husband (Ben Winspear) was killed in a car accident. A shadowy, spindly figure with a long black coat and a black hat, the Babadook is truly a frightening presence, funny name or not – and more so because it’s not clear what he wants. Perhaps he’s just an evil thing that’s moved into their lives because they’ve left a gap. Because he can.

There’s an overt European influence in the way the monster is embodied, yet there are Australian aspects to this film, too, such as the eerie, cicada-like hum we hear whenever the Babadook is near. Frank Lipson’s sound design – as with Alex Holmes’ production design, Radek Ladczuk’s cinematography, Jed Kurzel’s score and Simon Njoo’s editing – is meticulous. Tonally, Kent’s debut feature film is carefully calibrated. The Babadook represents the dreaded unknown, the Other. But at the same time, there’s something very familiar about him, evoking the sense of a communal childhood memory or a half-remembered nightmare.

The story begins gently, setting the scene. Amelia works as a nurse in an aged-care facility by day but her life revolves around her son. Her closest confidant is a kindly old neighbour called Mrs Roach (Barbara West), but even she is not fully trusted. After years alone together in their large house, Amelia and Samuel have become a little eccentric, so at first it’s no big deal when he is seen building catapults and other contraptions to protect himself from the ‘monster’ under his bed. But by the time both Amelia’s unsympathetic sister (Hayley McElhinney) and Samuel’s school get wind of this behaviour, it has become clear that this is a family in crisis. Either the child is troubled or disobedient and his mother isn’t coping, or they’re feeding each other’s paranoia into a folie à deux–type situation. Or the Babadook is real and extremely dangerous.

If you’re a fan of classic postmodern horror films such as The Innocents (Jack Clayton, 1961), Rosemary’s Baby (Roman Polanski, 1968) and The Shining (Stanley Kubrick, 1980), you’ll realise that making a clear determination one way or the other is not really the point. The enjoyment to be had is in puzzling out all the clues, weighing the evidence and slowly drawing conclusions. But unlike the Agatha Christie school of mystery, the focus here is not on the intricacies of the plot. Rather, the success of such films can be gauged from the potency and coherence of the emotional metaphor being explored, whether that be Rosemary’s (Mia Farrow) dread over first-time pregnancy, Miss Giddens’ (Deborah Kerr) sexual repression and loneliness in The Innocents, or Jack Torrance’s (Jack Nicholson) misogynistic rage in The Shining. Kent combines two of these elements in The Babadook. Her screenplay, partly developed at the prestigious Binger Lab in Amsterdam with support from Screen NSW and Screen Australia, concerns the terrors of parenthood, made incarnate in a monster created at the time of Amelia’s son’s birth. It also touches on her longing for intimacy, as we see her sadly watching romantic movies on television and unintentionally rebuffing the awkward overtures of a colleague (Daniel Henshall).

Amelia has created a tidy but cheerless world for Samuel – a house that’s equipped with necessities but eschews decoration or whimsy. A noteworthy exception is the vintage poster of Thurston the Great Magician displayed in Samuel’s room (with the tagline ‘Do the spirits come back?’), signposting his hobby of learning magic tricks as well as his longing to escape the day-to-day. The film’s muted grey-and-blue palette gradually gives way to splashes of red as the story becomes increasingly violent and intense, thereby bridging fear and grief with the all-important sense of being alive, of ‘full-bloodedness’. As the narrative tension rises, Amelia’s kitchen becomes messy and chaotic, her hair loosens from its bun, and at one point she even ends up in the bath with her clothes on (a dress the colour of old blood). Everything’s falling apart – yet the worse things get, the closer Amelia and Samuel are to a breakthrough, to understanding what’s real and true, what matters.

In the meantime, there are uncomfortable moments in which they not only doubt each other – sometimes Amelia seems to believe her son is evil, while Samuel is traumatised by his mother’s erratic attempts at discipline – but also overstep the bounds of decorum. A moment early in the film, when Amelia is irritated by her sleeping son’s foot resting on her, is telling. His nocturnal teeth-grinding rankles as well. Mothers are socially conditioned to restrain hostile feelings towards their children and, in turn, film audiences are not used to seeing expressions of these feelings. And, of course, it’s a scene that would be more commonly used to illuminate a marital relationship rather than a filial one. So from the beginning there’s a disturbing undertone, a sense of Amelia and Samuel being either too close or too adversarial – or perhaps both. Later, Amelia is interrupted by Samuel in a private moment, bringing to mind a similar mother–child incident in Black Swan (Darren Aronofsky, 2010). In The Babadook, the situation is depicted as more mundane, almost humorously, with the sound of a vibrator whirring under the covers stifled as the harried parent shifts her attention to her child. The implication is that she can’t extricate herself from him even for a moment, even for the most primal and personal of needs. ‘It’s a Freudian nightmare,’ to appropriate playwright Joe Orton.[2]Joe Orton, Loot, 1968.

Then again, Jungian analysis seems more apropos. There are scenes of teeth falling out, of discovering insects behind the wallpaper, of evil hiding in the basement, under the bed, even inside the television that an insomniac Amelia gazes into. If the house is a metaphor for Amelia’s psyche, then there are many hidden and potentially shameful aspects to who and what this woman is – all of which, it’s implied, can be exploited by the Babadook for his own nefarious purposes. As many a psychoanalyst would have had it, repression is the real toxin, not negative feelings in themselves. And in the tradition of the best fairytales, The Babadook is about coming to terms with the dark side of human experience: mortality, fear, anger, grief. There’s no way to eliminate these aspects of life, but, in facing them head-on, in paying tribute (a throwback to the earliest pagan incarnations of such beliefs), we can at least keep them under control. There is even a pleasing sense of ritual, along with nods to classic storytelling structures, such as knocking three times to summon the Babadook and repetitive incantations like ‘Let me in’ and ‘It isn’t real’.

But while the film has layers of meaning and interest, some viewers might find it difficult, as I did, to connect the symbolic struggle portrayed in The Babadook with the real world. The best horror stories work on both levels equally, whereas this narrative skews towards pure imagination. This, no doubt, is due in part to its origins as a short film, Kent’s stylish black-and-white Monster (2005). A short film, as with a short story, can leave much unexplained; the logic of a poem, or a song, is enough. But when such stories are fleshed out to feature length, loose ends can become problematic. Who has made and created the marvellous picture book that tells the story of the Babadook? When Amelia tears it to pieces and puts it in the garbage outside, and then it later turns up in the house, why is it sticky-taped back together? If it’s a magical book, not the product of human hands, wouldn’t tape be unnecessary?

Notwithstanding these criticisms, the film remains strong due to the extent to which it ‘goes there’, emotionally speaking. It sets up a situation and follows it through to the bitter end – and beyond. At times, Amelia is not just menaced by the malevolence of the Babadook; she’s possessed by it. Like Regan (Linda Blair) of The Exorcist (William Friedkin, 1973) all grown up, Essie Davis exhibits tremendous talent in expressing Amelia’s pain and anger physically – from crawling on the ground while making dreadful animal noises, to vomiting noxious black stuff all over the floor, to adopting a simian strength and agility. In other words, it’s an actor’s dream role and she rises to the occasion. Young Noah Wiseman is also more than apposite for his role with his effortless charisma and intensity. But Samuel’s journey feels a bit one-note, all spontaneity yet lacking a sufficiently counterbalancing guile (the likes of which we see in Martin Stephens’ Miles in The Innocents).

Ultimately, the relationship between the mother and son is what the film is all about; Kent herself has described it as a ‘love story’.[3]Jennifer Kent, ‘Director’s Statement’, in eOne Films, The Babadook press kit, p. 3. Yet comparisons to the The Shining are also revealing, in that the character of Amelia seems to embody both the feminine and the masculine – the nurturing protectiveness of Wendy (Shelley Duvall) and the unleashed aggression of Jack. In succeeding with such a bold representation of affection and antagonism, as much as for its technical and creative achievements, The Babadook is undeniably a powerful piece of filmmaking and heralds Kent as a significant new talent on the international scene.

The film was greeted with largely glowing reviews at its debut at Sundance in January. The Hollywood Reporter called it ‘impressive’ and ‘[d]riven by a ripper of a performance’,[4]David Rooney, ‘The Babadook: Sundance Review’, The Hollywood Reporter, 21 January 2014,

<http://www.hollywoodreporter.com/review/babadook-sundance-review-673048/>, accessed 22 January 2014. Fangoria said it was ‘stylish, aurally assaulting and often tremendous’,[5]Samuel Zimmerman, ‘The Babadook (Sundance Movie Review)’, Fangoria, 18 January 2014, <http://www.fangoria.com/new/the-babadook-sundance-movie-review/>, accessed 6 February 2014. while Ain’t It Cool News’ Kraken enthused:

I haven’t had a midnight horror movie unsettle me this much at a film festival since I saw the original Japanese Ju-On: The Grudge [Takashi

Shimizu, 2004] over a decade ago.[6]Kraken (Aaron Morgan), ‘Sundance Midnight Selection The Babadook Made Kraken’s Sphincter Tighten!’, Ain’t It Cool News, 18 January 2014, <http://www.aintitcool.com/node/65800>, accessed 22 January 2014.

This was soon followed by Screen Daily announcing that the film had secured a distribution deal with the Paris-based Wild Bunch for the European market,[7]Jeremy Kay, ‘Wild Bunch Moves on Babadook’, Screen Daily, 20 January 2014, <http://www.screendaily.com/festivals/sundance/sundance-news/wild-bunch-moves-on-babadook/5065579.article>, accessed 22 January 2014. and by Variety reporting that IFC Midnight had secured US rights.[8]Dave McNary, ‘Sundance: IFC Midnight Takes Horror Movie The Babadook’, Variety, 25 January 2014, <http://variety.com/2014/film/news/sundance-ifc-midight-takes-horror-movie-the-babadook-1201070789/>, accessed 4 March 2014. Wild Bunch’s Jerome Rougier said of the film:

Incredibly scary of course but also very smart and stylish, Jennifer Kent’s film easily matches recent outstanding horror films like The Orphanage [Juan Antonio Bayona, 2007] or Insidious [James Wan, 2010] and we couldn’t be more excited to release it.[9]Kay, op. cit.

The Babadook’s success bodes well for the future of Australian genre filmmaking. It also vindicates the recent investment in nurturing new talent in South Australia, where the project was shot. (On the other hand, the suggestion in the New York Post that it will be remade by Hollywood with a ‘name cast’ is rather less inspiring.[10]Kyle Smith, ‘Sundance Horror Flick The Babadook Ripe for Remake’, New York Post, 22 January 2014, <http://nypost.com/2014/01/22/sundance-horror-flick-the-babadook-ripe-for-remake/>, accessed 23 January 2014.) Aficionados may be unimpressed, however, with the efforts of the domestic distributor, Umbrella Entertainment, to market the film as a ‘psychological thriller’. Minimising The Babadook’s place within the context of horror is odd, especially given the film’s explicit references to the touchstones of the genre, including The Cake-Walk Infernal (Georges Méliès, 1903) and Black Sabbath (Mario Bava, 1963). It also covers similar ground to recent box-office triumph The Conjuring (James Wan, 2013), also by an Australian director. Both films deal with the intensity of motherhood and the claustrophobia of the domestic sphere, and while they do so quite differently, both rely on practical effects and a creaky haunted-house aesthetic.

This brings me to another notable aspect of The Babadook: its awareness of cinematic traditions. The Babadook itself is presented as an old-fashioned monster – roughly hewn from the imagination, if you will – not 3D-printed into existence by Hollywood. Kent remarked on this at Sundance:

Anyone who knows these kinds of childlike pop-up books and, you know, a lot of the German Expressionist stuff, it has a very handmade quality to it. And to be faithful to that and get the tone of that through the film, I really didn’t want to use any special effects at all. So the only stuff we have here is smoothing post stuff […] everything’s done in camera.[11]Jennifer Kent, Sundance post-screening Q&A, 18 January 2014, available on YouTube, <http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=u02Y1Eqn58M>, accessed 22 January 2014.

In other words, it’s one for the film fans. If the critical response to date is any indication, most viewers will overlook the script’s flaws in appreciation of Kent’s enthusiasm for the filmmakers who have paved the way for her and for the story she is passionately telling.

http://www.causewayfilms.com.au/#!the-babadook

Endnotes

| 1 | Jean-Paul Sartre, No Exit, 1944. |

|---|---|

| 2 | Joe Orton, Loot, 1968. |

| 3 | Jennifer Kent, ‘Director’s Statement’, in eOne Films, The Babadook press kit, p. 3. |

| 4 | David Rooney, ‘The Babadook: Sundance Review’, The Hollywood Reporter, 21 January 2014, <http://www.hollywoodreporter.com/review/babadook-sundance-review-673048/>, accessed 22 January 2014. |

| 5 | Samuel Zimmerman, ‘The Babadook (Sundance Movie Review)’, Fangoria, 18 January 2014, <http://www.fangoria.com/new/the-babadook-sundance-movie-review/>, accessed 6 February 2014. |

| 6 | Kraken (Aaron Morgan), ‘Sundance Midnight Selection The Babadook Made Kraken’s Sphincter Tighten!’, Ain’t It Cool News, 18 January 2014, <http://www.aintitcool.com/node/65800>, accessed 22 January 2014. |

| 7 | Jeremy Kay, ‘Wild Bunch Moves on Babadook’, Screen Daily, 20 January 2014, <http://www.screendaily.com/festivals/sundance/sundance-news/wild-bunch-moves-on-babadook/5065579.article>, accessed 22 January 2014. |

| 8 | Dave McNary, ‘Sundance: IFC Midnight Takes Horror Movie The Babadook’, Variety, 25 January 2014, <http://variety.com/2014/film/news/sundance-ifc-midight-takes-horror-movie-the-babadook-1201070789/>, accessed 4 March 2014. |

| 9 | Kay, op. cit. |

| 10 | Kyle Smith, ‘Sundance Horror Flick The Babadook Ripe for Remake’, New York Post, 22 January 2014, <http://nypost.com/2014/01/22/sundance-horror-flick-the-babadook-ripe-for-remake/>, accessed 23 January 2014. |

| 11 | Jennifer Kent, Sundance post-screening Q&A, 18 January 2014, available on YouTube, <http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=u02Y1Eqn58M>, accessed 22 January 2014. |