Heatwave joins a growing list of films set in contemporary urban Australia which combine an interpretation of important issuces with a visual essay on the city which provides the physical setting. Sometimes, as in the case of Duigan’s Mouth to Mouth and Winter of Our Dreams, the issues dominate, and the cities, Melbourne in one case, and Sydney in the other, act as backdrops that occasionally intrude into the foreground. In Peter Weir’s Last Wave, atmosphere and cityscape are dominant, and are used to create a sinister feel. In Heatwave director Phil Noyce creates both an essay on social issues which have been prominent in recent city politics, as well as a vision of the physical environment that impinges on these events and the characters portrayed. It is, in the director’s own words, an attempt to provide “a subjective portrait of living in contemporary Sydney – a mosaic of social realism and surrealism.”

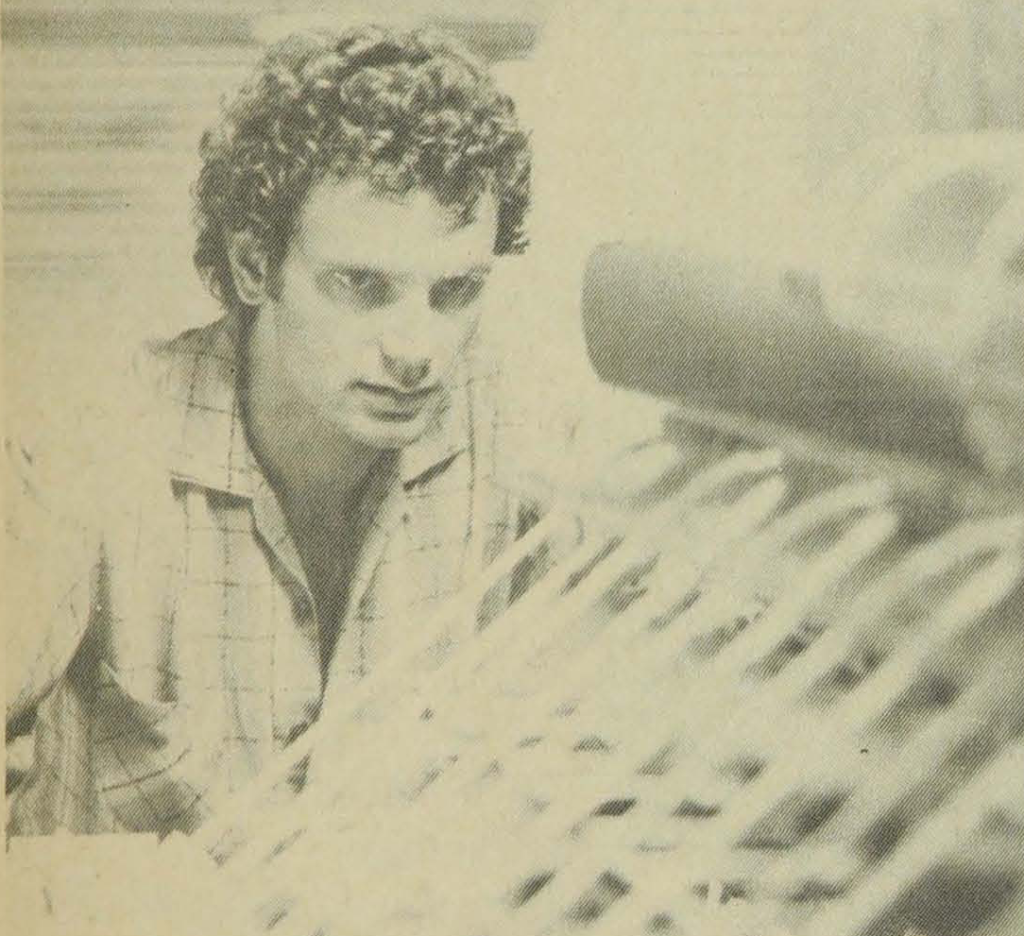

Lurking in the background as the inspiration to the events in both Heatwave and the thematically similar The Killing of Angel Street is the disappearance in the mid-seventies of Sydney housing activist Juanita Nielson. In Heatwave resident campaigner Mary Kelly (Carole Skinner) disappears in somewhat similar circumstances. She has been the driving force behind a group of local residents fighting to save their homes from the bulldozers of private property developers. Their dwellings are to be replaced by a $200,000,000 residential complex, designed by architect Stephen West (Richard Moir) for developer Peter Houseman, who is ably portrayed by Chris Haywood as a crude, colourful, high living, get rich quick cockney, who has built up a fragile empire based on a series of modern high rise complexes.

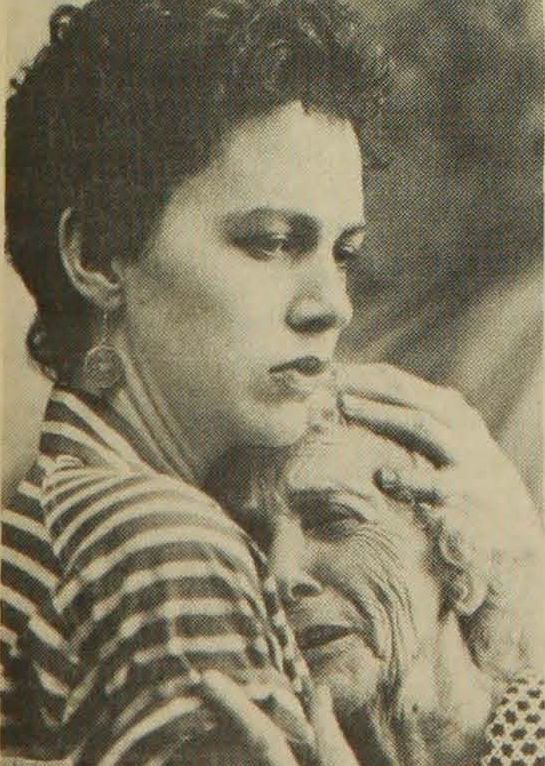

After Mary’s disappearance, her role as spearhead of the residents’ movement is taken on by a young radical activist Kate Dean (Judy Davis), who is driven by a passionate hatred of the aims of the developers. She becomes obsessed with unravelling the mystery of Mary’s disappearance, and with keeping the residents’ struggle afloat in the face of the growing power of her opponents.

The film evolves through a series of interlocking plots that include the machinations of an ambitious corporate lawyer, the sinister dealings of a strip club owner complete with ruthless, cigar smoking bodyguard, the shifting alliances of rival building unions, and the erosion of architect Stephen West’s vision of creating a futuristic residential complex that could revolutionise city, high rise living.

Heatwave is, in most instances, intense, committed and compelling cinema. Audiences should be attracted by its sustained tension and well paced structure that builds up towards a spectacular finale among the thousands of revellers that crowd Kings Cross on New Year’s eve. It is an atmospheric film with an almost hypnotic effect created by the movement of the camera, tight rhythmic editing and a repetitive, surreal soundtrack composed by Cameron Allan. This is augmented by the occasional shriek of a cicada, the crackle of a test cricket broadcast, and the final crashing downpour of a cleansing rainstorm which breaks the relentless Christmas to New Year heatwave.

The actors are well directed, with yet another impressive performance from Judy Davis. Her role as the anarchic Kate Dean is reminiscent of her acting in Winter of Our Dreams. She creates a character that blends strength and vulnerability, displaying a unique range of feelings that surface in subtle gestures. Richard Moir as the visionary architect acts with a quiet intensity that suits the part. He uses restraint and understatement to reveal subtle changes of feeling as he gradually sees his architectural ideal whittled away to a sellout.

Despite its overall integrity, some aspects of the film seemed to fall for well worn formulas. One instance is the overkill used in the character of Barbie Lee Taylor, the stripper and prostitute. Certainly Sydney’s Kings Cross provides an authentic backdrop to her drugged strip teasing in front of a leering male audience. But there is an uneasy feeling that she is there as part of a formula, perhaps picked up from U.S. thrillers to attract the filmgoer. The relationship between Steve and Kate has an awkward feel to it. Whilst much of the script is well controlled with flashes of cutting humour and succinct dialogue, the scripting of Kate and Steve’s growing affection for each other falls victim to cliché. Once again it seems to be there for the formula. The script is good enough without the obligatory romantic interlude.

Phil Noyce’s firm and imaginative direction places him amongst the few Australian filmmakers who are working toward a cinematic language appropriate to the issues alive in contemporary Australia.

Despite the inveterate problem of maintaining the standard of coverage of these issues while keeping an eye on the box-office, and despite the limits of the cinematic medium in providing thorough analysis of social issues, Heatwave successfully raises and examines some of the social, economic and moral conflicts inherent in recent urban property development.

It shows the uneasy alliance between middle class activist and working class tenant, the role of the unions and the values of an emerging class of nouveau riche speculators. With an almost larrikin daring, Heatwave underscores the speculators’ crude rationalizations so succinctly put by Houseman when pointing to the high rise boxes, “they’re as ugly as sin. But they’ve put a roof over many people’s heads – and they’ve made me heaps.”