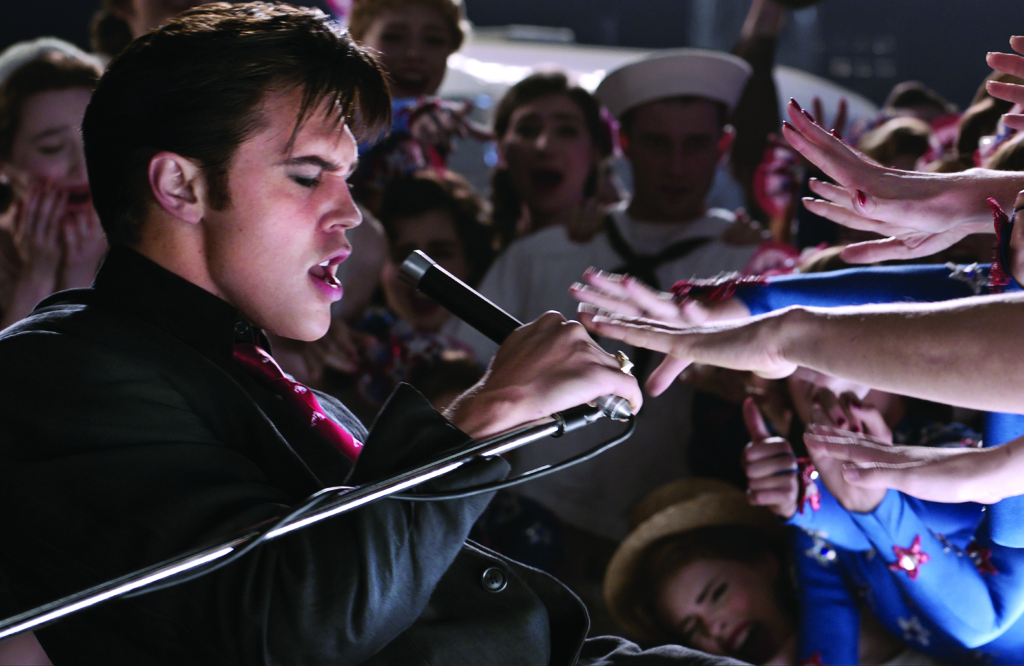

In a widely circulated social media teaser for Baz Luhrmann’s frenzied new film about Elvis Presley,[1]Elvis teaser, Facebook video, 4 July 2022, <https://www.facebook.com/ElvisMovie/videos/2257399781091842/>, accessed 10 July 2022. a pink-suited Elvis (Austin Butler) shakes and shimmies uncontrollably on stage as anachronistic electric guitar riffs intensify on the soundtrack and female audience members scream hysterically, grabbing desperately at the young idol. An ominous voiceover spells out what we are seeing: ‘I watched that skinny boy transform into a superhero.’

Luhrmann has made it very clear in the press surrounding Elvis (2022), as well as in the film itself, that he has chosen to frame the so-called ‘king’ of rock’n’roll as ‘the original superhero’.[2]Baz Luhrmann, quoted in Samantha Bergeson, ‘Baz Luhrmann’s Elvis Is “Not Really a Biopic” but an Ode to the “Original Superhero” Presley’, IndieWire, 26 April 2022, <https://www.indiewire.com/2022/04/baz-luhrmanns-elvis-not-biopic-original-superhero-1234719986/>, accessed 17 July 2022. Besides imbuing the title character’s live performances – which build in intensity until his musical power erupts and elicits uncontrollable fan responses – with an almost spiritual reverence, the film also includes an early animated sequence that inserts a very young Elvis (Chaydon Jay) into his beloved Captain Marvel Jr. comic book. Though Luhrmann has also claimed that Elvis is ‘not really a biopic’,[3]ibid. it’s more accurate to say that the director has transformed the already popular modern music biographical picture into a format today’s moviegoers are intimately familiar with.

It’s a natural progression when you consider that most music biopics are, in superhero terms, origin stories.[4]Writing about the film Walk Hard: The Dewey Cox Story (Jake Kasdan, 2007), Brianna Zigler notes that the music biopics it parodies ‘all follow the same formula: The same tired cliches, the same name-drops and celebrity cameos and origin stories now implicit to every modern American blockbuster’. Zigler, ‘Will We Ever Learn from Walk Hard?’, Paste, 24 June 2022, <https://www.pastemagazine.com/movies/walk-hard-kill-music-biopics/>, accessed 22 August 2022. Furthermore, the cult of celebrity – and particularly that of male rock stars – dictates that their subjects are already worshipped as heroes. Framing musical ability and star power as a superpower isn’t much of a stretch, and it makes excellent financial sense in today’s blockbuster landscape.

This move into comic-book territory sees Elvis depart from other popular-music biopics in its adherence to a strict ‘Good versus Evil’ framework. The second component of that dichotomy is embodied by Colonel Tom Parker (Tom Hanks), Presley’s long-time manager, whom Luhrmann transforms into a towering, cartoonish villain. While this binary approach simplifies things enough for Luhrmann’s trademark kinetic chaos to flourish without confounding viewers, it precludes any exploration of Elvis’ own moral complexity; he is the film’s superhero, and therefore he is Good.

Thus, Elvis’ destructive reliance on uppers and downers is framed as a response to the Colonel forcing him to reject his creative instincts and sell out to Hollywood. Later, the Colonel arranges a suspicious doctor to maintain a steady supply of drugs so the singer can fulfil the extreme demands of his lucrative Las Vegas hotel residency. Elvis’ substance abuse leads his wife Priscilla (Olivia DeJonge) to leave him, and it is heavily implied that his drug-facilitated overwork is the cause of his early death at the age of forty-two. Elvis is not held accountable for any of this; all transgressions and misfortune can be traced back to the film’s villain.

While elevating rock stars to hero status is standard in the genre, it’s rare for such films to deny their subjects’ fallibility. Rock’n’roll is synonymous with bad behaviour, from illicit drug use and indiscriminate sex to trashing hotel rooms, and rock biopics regularly depict scenes of this nature. Many go further, showing how the reckless conduct of popular musicians hurts their loved ones, a plot point that is commonly used as a vehicle for a redemptive third act.[5]For example, in Ray (Taylor Hackford, 2004), Ray Charles’ (Jamie Foxx) infidelity and crippling heroin addiction are eventually overcome in the final minutes of the film; while in Walk the Line (James Mangold, 2005), Johnny Cash (Joaquin Phoenix) treats both his first and second wives horribly before getting clean. Though this approach doesn’t fully reckon with the complex legacy of hurt that runs through (male) rock history,[6]See, for example, Lucy Mangan, ‘Look Away Review – Horrifying Stories of Abuse at the Hands of Rock Stars’, The Guardian, 14 September 2021, <https://www.theguardian.com/tv-and-radio/2021/sep/13/look-away-review-horrifying-stories-of-abuse-at-the-hands-of-male-rock-stars>, accessed 26 July 2022. it’s fair to expect a film about Presley – a monumental figure in that history – to at least meet this minimum standard of honesty. On the contrary, through its insistence on turning its protagonist into a superhero, Elvis falls woefully short of meaningfully engaging with two of rock’s most significant moral and political quandaries.

Whitewashing abuse

The most persistent problem running through the history of popular music over the past century has been the mistreatment endured by women and girls. At the core of this is the gender imbalance inherent in the industry: though some female musicians have of course been very successful, in the pages of rock history many more women have been relegated to the roles of fan, wife, groupie or muse to male musicians. This disparity remains a serious problem in today’s music industry,[7]According to a study that looked at the popular music industry in the US from 2012 to 2019, women accounted for just 12.5 per cent of songwriters and less than 3 per cent of producers. See Andrea Bossi, ‘Women Are Missing in the Music Industry, Make Up Less than 3% of Producers’, Forbes, 22 January 2020, <https://www.forbes.com/sites/andreabossi/2020/01/22/women-are-missing-in-the-music-industry-less-than-3-are-producers/?sh=6672369d4f1e>, accessed 16 July 2022. with studies attributing it to factors like ageism, male-dominated resources, and sexual harassment and abuse.[8]Andrea Bossi, ‘These Are 3 of the Biggest Drivers of Gender Inequality in Music’, Forbes, 26 March 2021, <https://www.forbes.com/sites/andreabossi/2021/03/26/these-are-3-of-the-biggest-reported-drivers-of-gender-inequality-in-music/?sh=51ce5cf86290>, accessed 16 July 2022. In the popular music scene, as sociologist Catherine Strong and ethicist Emma Rush put it, ‘respecting women’s dignity and autonomy has often been treated as optional’.[9]Catherine Strong & Emma Rush, ‘Musical Genius and/or Nasty Piece of Work? Dealing with Violence and Sexual Assault in Accounts of Popular Music’s Past’, Continuum: Journal of Media & Cultural Studies, vol. 32, no. 5, 2018, pp. 569–80.

Stories about early rock’n’roll stars are rife with the mistreatment of girls and women (many instances of which involved statutory rape).[10]For example, in 1959, an adult Chuck Berry was arrested for transporting a fourteen-year-old girl across state borders; while in 1957, a 22-year-old Jerry Lee Lewis married his thirteen-year-old cousin. See Hadley Freeman, ‘Singer, Musician, Sex Offender: Let’s Remember the Whole Chuck Berry’, The Guardian, 25 March 2017, <https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2017/mar/25/singer-musician-sex-offender-lets-remember-the-whole-chuck-berry>, accessed 16 July 2022. Presley’s is no exception – but you won’t learn that from watching Elvis.

In Luhrmann’s film, Priscilla Presley plays a minor role in the context of Elvis’ life, and exists primarily as a token love interest for our superhero. We first meet her when Elvis is stationed in Germany: she is in his bedroom, pacing back and forth as she confidently and energetically relays a story about her parents. He looks up at her from the floor where he is sitting, in awe. ‘I’ve never met anyone like you,’ he marvels. They kiss as a version of ‘Can’t Help Falling in Love’ swells on the soundtrack.

A rapid sequence follows, in which ten years are condensed into ten minutes: Elvis and Priscilla reunite in America, get married and have a baby. Later, we see her leave him, acknowledging his infidelities but citing his drug use as the main reason she won’t stay. Near the end of the film, the two meet again on an airport tarmac, where she urges her unhealthy and unhappy former husband to go to rehab. As he leaves to board his jet, he turns to her and mouths the words ‘I will always love you.’ The foggy, theatrical mise en scène and overt ‘doomed romance’ theme is obviously referencing the final scene of Casablanca (Michael Curtiz, 1942) – one of the most famous romantic sequences in Hollywood history. The message is clear: theirs was a great love, foiled only by the misery that the Colonel’s destructive control inflicted on Elvis.

In fact, the real-life Priscilla was only fourteen years old when a 24-year-old Presley began pursuing her. In her 1985 autobiography Elvis and Me, she describes their early meetings with details that seek to emphasise his chivalrous restraint but are now startlingly recognisable as signs of grooming. Priscilla recounts that on their second rendezvous, at his house, he told her he wanted to be alone with her. Her description of these events offers a stark contrast to Elvis’ bedroom scene:

‘We are alone,’ I replied nervously.

He moved closer, backing me against the wall. ‘I mean really alone,’ he whispered. ‘Will you come upstairs to my room?’

The question threw me into a panic […]

He took my hand and led me toward the stairs, whispering which room was his, and said, ‘You go on ahead, and I’ll join you in a few minutes. It looks better.’[11]Priscilla Beaulieu Presley with Sandra Harmon, Elvis and Me, Berkley Books, New York, 1985, pp. 31–2. Emphasis in original.

Upstairs, he kissed her:

My first real kiss. I had never experienced such a mixture of affection and desire. I was speechless […] Aware of my response – and my youth – he broke away first, saying, ‘We have plenty of time, Little One.’ He kissed my forehead and sent me home.[12]ibid., p. 35.

As their relationship developed, unhealthy and increasingly coercive behaviours continued. Priscilla writes that, from the beginning, Presley was open about wanting to mould her into his ‘ideal woman’;[13]ibid., p. 115. he controlled what she did (a career was out of the question), whom she could see, how she looked and even what she thought;[14]‘His tastes, his insecurities, his hang-ups – all became mine,’ Priscilla writes. See ibid., p. 135. his infidelities were numerous, even as he made it clear that a woman’s fidelity was paramount; and he threatened to send her back to Germany if she defied him.[15]ibid., p. 179. In Priscilla’s words, ‘Over the years he became my father, husband, and very nearly God.’[16]ibid., p. 15.

Luhrmann’s staggering decision to turn Priscilla into a classic love interest – and depict Presley as the passive receiver of her charms – becomes more baffling in light of reports that Presley seems to have had a penchant for underage girls even after his divorce.[17]See Elizabeth King, ‘Elvis Was the King of Treating Women Like Shit and Luring 14-year-olds into Bed’, Vice, 8 October 2016, <https://www.vice.com/en/article/3k8z39/elvis-was-the-king-of-treating-women-like-shit-and-luring-14-year-olds-into-bed>, accessed 16 July 2022. Presley’s treatment of his wife as an object on which to project his desires is emblematic of the chronic tendency of male rock stars to use women as just another prize they are entitled to.[18]Strong and Rush point out that the mistreatment of women has ‘essentially been normalized in many parts of an industry where access to women has always been touted as one of the perks of success’, and even suggest that violence against women ‘could be considered a normalized part of popular music culture’. See Strong & Rush, op. cit., pp. 570, 577. To erase this from Presley’s story in the service of presenting him as an infallible rock god does a massive disservice to music fans and to women.

Race, appropriation and erasure

Race has long been a significant point of contention in Presley’s career. A persistent (if crude) element of the Elvis Presley mythology is that he took music popularised by African-American musicians and made it palatable to white audiences in a way that Black artists couldn’t in 1950s America. While some critics argue that it’s more complex – Presley was influenced by multiple genres, and put his unique spin on them to create something original[19]See, for example, Andrew Hickey, ‘The King’, Andrew Hickey blog, 9 January 2015, <https://andrewhickey.info/2015/01/09/the-king/>, accessed 16 July 2022. For a detailed analysis of Presley’s varied influences and appeal, see Ann Powers, ‘Teen Dreams and Grown-up Urges’, in Powers, Good Booty: Love and Sex, Black & White, Body and Soul in American Music, Dey Street Books, New York, 2018, pp. 123–35. – the sentiment that he exploited African-American musicians remains.[20]See Helen Kolawole, ‘He Wasn’t My King’, The Guardian, 15 August 2002, <https://www.theguardian.com/music/2002/aug/15/elvis25yearson.elvispresley>, accessed 16 July 2022.

Luhrmann goes to some lengths to acknowledge Presley’s debt to Black artists. Arthur ‘Big Boy’ Crudup (Gary Clark Jr), Little Richard (Alton Mason), BB King (Kelvin Harrison Jr), Big Mama Thornton (Shonka Dukureh), Sister Rosetta Tharpe (Yola) and Mahalia Jackson (Cle Morgan) all feature in the film, depicted as having had often-profound impacts on Elvis throughout his life and career.

When these characters are understood within the superhero framework of the film, Luhrmann’s approach becomes troubling. The Colonel claims early in the film that Elvis’ superpower is music – but it is, more accurately, Black music. We see Elvis sneak into an African-American church’s gospel service as a child, where he is raised up by the community in a Jesus Christ pose as the music appears to possess him. The film is structured around several key points of musical triumph for Elvis, including his first big performance (the pink-suit scene highlighted in the teaser); his rebellious performance of ‘Trouble’; his politically charged rendition of ‘If I Can Dream’; and his first Las Vegas show, during which he transforms his original hit ‘That’s All Right’ into a big-band spectacular.

These last three performances exist in opposition to the Colonel: Elvis’ creative brilliance wins out over the evil of his manager’s commercial motivations. Importantly, each performance is also directly influenced by an African-American musician, whether because the song was originally theirs (the film cuts back to a young Elvis watching Crudup perform his original version of ‘That’s All Right’) or because a Black artist has advised Elvis directly (King urges him to follow his instincts before ‘Trouble’; Elvis recalls Jackson’s advice to sing what can’t be spoken before ‘If I Can Dream’). In these sequences, Elvis channels the skill and wisdom of Black artists to engage his superpower.

Not only does this reductive approach mask any negative impacts Elvis’ association with these musicians may have had on them – Crudup, for example, never received remuneration for ‘That’s All Right’ despite being credited as its composer[21]Brian Lukasavitz, ‘Blues Law: Arthur “Big Boy” Crudup vs. Lester Melrose’, American Blues Scene, updated 10 April 2020, <http://www.americanbluesscene.com/2015/11/blues-law-arthur-big-boy-crudup-vs-lester-melrose/>, accessed 16 July 2022. – it also veers perilously close to the Magical Negro trope. This persistent screen figure is typically a Black character whose (often supernatural) abilities and/or profound wisdom aids the white protagonist; in other words, this character exists only in relation to their white counterpart.[22]For an overview of the trope, see Nnedi Okorafor-Mbachu, ‘Stephen King’s Super-duper Magical Negroes’, Strange Horizons, 25 October 2004, archived at <https://web.archive.org/web/20061114013842/http:/www.strangehorizons.com/2004/20041025/kinga.shtml>, accessed 16 July 2022. The use of this trope reinforces negative racial stereotypes, implying that Black people are ‘inferior and expendable’, as novelist Nnedi Okorafor-Mbachu argues.[23]ibid. One study has even linked the trope to real-world violence against Black people.[24]Adam Waytz, Kelly Marie Hoffman & Sophie Trawalter, ‘A Superhumanization Bias in Whites’ Perceptions of Blacks’, Social Psychological and Personality Science, vol. 6, no. 3, 2015, pp. 352–9.

For critic Jack Hamilton, Black characters in Elvis ‘exist as props whose primary function is to vouch for Elvis’ own mythic racial transcendence’.[25]Jack Hamilton, ‘Elvis Is a Con’, Slate, 27 June 2022, <https://slate.com/culture/2022/06/elvis-movie-2022-austin-butler-tom-hanks-racist.html>, accessed 16 July 2022. Indeed, though Elvis occasionally acknowledges racial injustices, such as when King points out that a Black artist would never be able to make a song as successful as Elvis could, this operates primarily to reinforce the protagonist’s social consciousness. At key points, the film goes so far as to position Elvis as a civil rights leader, such as when his performance of ‘Trouble’ prompts the liberated audience to tear down the segregation rope.[26]In reality, Presley’s commitment to civil rights is still subject to debate, with some music historians arguing that his support for the movement has been over-egged. See Kaleem Aftab, ‘Who Was the Real Elvis Presley?’, BBC Culture, 27 June 2022, archived at <https://web.archive.org/web/20220626231952/https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20220624-who-was-the-real-elvis-presley>, accessed 26 July 2022.

In his determination to elevate his hero to a higher moral plane, Luhrmann has, as critic Robert Daniels describes it, endeavoured ‘to smooth over the complicated feelings many Black folks of varied generations have toward the purported King’.[27]Robert Daniels, ‘Elvis’, RogerEbert.com, 22 June 2022, <https://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/elvis-movie-review-2022>, accessed 16 July 2022. By employing the Magical Negro trope in the process, he ultimately perpetuates damagingly simplistic ideas about race.

A rose-tinted lens

Luhrmann is aware of how vital Presley is to understanding the United States as a country. ‘If you want to talk about America in the 50s and 60s and 70s,’ he has said, ‘at the center of culture, for the good the bad and the ugly, was Elvis.’[28]Luhrmann, quoted in Bergeson, op. cit. As a non-American filmmaker, Luhrmann had an advantageous position to critically examine key elements of US culture via Presley’s story. And his choices around this are important to inspect, because Elvis has been a huge commercial success;[29]At the time of writing, Elvis had made over US$276 million in box office receipts globally. See Andrew Korpan, ‘Elvis Global Box Office Crosses $276 Million’, Collider, 28 August 2022, <https://collider.com/elvis-movie-276-million-global-box-office/>, accessed 14 September 2022. like other biopics that have reached large audiences, the film will, for many viewers, become the dominant cultural narrative about its central figure – and, to some extent, about rock’n’roll history itself.

In sidestepping this opportunity for critical assessment, particularly as it relates to issues around racism and misogyny that continue to devastate the country for which Presley has been such a central cultural figure,[30]Two of the most globally publicised social issues to emerge from the United States in recent years have been police violence against African-Americans (and the associated Black Lives Matter movement), and the overturning of the US Supreme Court’s 1973 Roe v. Wade ruling, which has removed barriers to abortion being made illegal in many states. See Leah Asmelash, ‘How Black Lives Matter Went from a Hashtag to a Global Rallying Cry’, CNN, 26 July 2020, <https://edition.cnn.com/2020/07/26/us/black-lives-matter-explainer-trnd/index.html>; and Nina Totenberg & Sarah McCammon, ‘Supreme Court Overturns Roe v. Wade, Ending Right to Abortion Upheld for Decades’, NPR, updated 24 June 2022, <https://www.npr.org/2022/06/24/1102305878/supreme-court-abortion-roe-v-wade-decision-overturn>, both accessed 15 August 2022. Elvis feels less like a missed opportunity and more like a dangerous ideological product – one that uncritically immortalises the superhero at its heart, along with an idealised vision of the United States that should have long ago been dispensed with.

Endnotes

| 1 | Elvis teaser, Facebook video, 4 July 2022, <https://www.facebook.com/ElvisMovie/videos/2257399781091842/>, accessed 10 July 2022. |

|---|---|

| 2 | Baz Luhrmann, quoted in Samantha Bergeson, ‘Baz Luhrmann’s Elvis Is “Not Really a Biopic” but an Ode to the “Original Superhero” Presley’, IndieWire, 26 April 2022, <https://www.indiewire.com/2022/04/baz-luhrmanns-elvis-not-biopic-original-superhero-1234719986/>, accessed 17 July 2022. |

| 3 | ibid. |

| 4 | Writing about the film Walk Hard: The Dewey Cox Story (Jake Kasdan, 2007), Brianna Zigler notes that the music biopics it parodies ‘all follow the same formula: The same tired cliches, the same name-drops and celebrity cameos and origin stories now implicit to every modern American blockbuster’. Zigler, ‘Will We Ever Learn from Walk Hard?’, Paste, 24 June 2022, <https://www.pastemagazine.com/movies/walk-hard-kill-music-biopics/>, accessed 22 August 2022. |

| 5 | For example, in Ray (Taylor Hackford, 2004), Ray Charles’ (Jamie Foxx) infidelity and crippling heroin addiction are eventually overcome in the final minutes of the film; while in Walk the Line (James Mangold, 2005), Johnny Cash (Joaquin Phoenix) treats both his first and second wives horribly before getting clean. |

| 6 | See, for example, Lucy Mangan, ‘Look Away Review – Horrifying Stories of Abuse at the Hands of Rock Stars’, The Guardian, 14 September 2021, <https://www.theguardian.com/tv-and-radio/2021/sep/13/look-away-review-horrifying-stories-of-abuse-at-the-hands-of-male-rock-stars>, accessed 26 July 2022. |

| 7 | According to a study that looked at the popular music industry in the US from 2012 to 2019, women accounted for just 12.5 per cent of songwriters and less than 3 per cent of producers. See Andrea Bossi, ‘Women Are Missing in the Music Industry, Make Up Less than 3% of Producers’, Forbes, 22 January 2020, <https://www.forbes.com/sites/andreabossi/2020/01/22/women-are-missing-in-the-music-industry-less-than-3-are-producers/?sh=6672369d4f1e>, accessed 16 July 2022. |

| 8 | Andrea Bossi, ‘These Are 3 of the Biggest Drivers of Gender Inequality in Music’, Forbes, 26 March 2021, <https://www.forbes.com/sites/andreabossi/2021/03/26/these-are-3-of-the-biggest-reported-drivers-of-gender-inequality-in-music/?sh=51ce5cf86290>, accessed 16 July 2022. |

| 9 | Catherine Strong & Emma Rush, ‘Musical Genius and/or Nasty Piece of Work? Dealing with Violence and Sexual Assault in Accounts of Popular Music’s Past’, Continuum: Journal of Media & Cultural Studies, vol. 32, no. 5, 2018, pp. 569–80. |

| 10 | For example, in 1959, an adult Chuck Berry was arrested for transporting a fourteen-year-old girl across state borders; while in 1957, a 22-year-old Jerry Lee Lewis married his thirteen-year-old cousin. See Hadley Freeman, ‘Singer, Musician, Sex Offender: Let’s Remember the Whole Chuck Berry’, The Guardian, 25 March 2017, <https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2017/mar/25/singer-musician-sex-offender-lets-remember-the-whole-chuck-berry>, accessed 16 July 2022. |

| 11 | Priscilla Beaulieu Presley with Sandra Harmon, Elvis and Me, Berkley Books, New York, 1985, pp. 31–2. Emphasis in original. |

| 12 | ibid., p. 35. |

| 13 | ibid., p. 115. |

| 14 | ‘His tastes, his insecurities, his hang-ups – all became mine,’ Priscilla writes. See ibid., p. 135. |

| 15 | ibid., p. 179. |

| 16 | ibid., p. 15. |

| 17 | See Elizabeth King, ‘Elvis Was the King of Treating Women Like Shit and Luring 14-year-olds into Bed’, Vice, 8 October 2016, <https://www.vice.com/en/article/3k8z39/elvis-was-the-king-of-treating-women-like-shit-and-luring-14-year-olds-into-bed>, accessed 16 July 2022. |

| 18 | Strong and Rush point out that the mistreatment of women has ‘essentially been normalized in many parts of an industry where access to women has always been touted as one of the perks of success’, and even suggest that violence against women ‘could be considered a normalized part of popular music culture’. See Strong & Rush, op. cit., pp. 570, 577. |

| 19 | See, for example, Andrew Hickey, ‘The King’, Andrew Hickey blog, 9 January 2015, <https://andrewhickey.info/2015/01/09/the-king/>, accessed 16 July 2022. For a detailed analysis of Presley’s varied influences and appeal, see Ann Powers, ‘Teen Dreams and Grown-up Urges’, in Powers, Good Booty: Love and Sex, Black & White, Body and Soul in American Music, Dey Street Books, New York, 2018, pp. 123–35. |

| 20 | See Helen Kolawole, ‘He Wasn’t My King’, The Guardian, 15 August 2002, <https://www.theguardian.com/music/2002/aug/15/elvis25yearson.elvispresley>, accessed 16 July 2022. |

| 21 | Brian Lukasavitz, ‘Blues Law: Arthur “Big Boy” Crudup vs. Lester Melrose’, American Blues Scene, updated 10 April 2020, <http://www.americanbluesscene.com/2015/11/blues-law-arthur-big-boy-crudup-vs-lester-melrose/>, accessed 16 July 2022. |

| 22 | For an overview of the trope, see Nnedi Okorafor-Mbachu, ‘Stephen King’s Super-duper Magical Negroes’, Strange Horizons, 25 October 2004, archived at <https://web.archive.org/web/20061114013842/http:/www.strangehorizons.com/2004/20041025/kinga.shtml>, accessed 16 July 2022. |

| 23 | ibid. |

| 24 | Adam Waytz, Kelly Marie Hoffman & Sophie Trawalter, ‘A Superhumanization Bias in Whites’ Perceptions of Blacks’, Social Psychological and Personality Science, vol. 6, no. 3, 2015, pp. 352–9. |

| 25 | Jack Hamilton, ‘Elvis Is a Con’, Slate, 27 June 2022, <https://slate.com/culture/2022/06/elvis-movie-2022-austin-butler-tom-hanks-racist.html>, accessed 16 July 2022. |

| 26 | In reality, Presley’s commitment to civil rights is still subject to debate, with some music historians arguing that his support for the movement has been over-egged. See Kaleem Aftab, ‘Who Was the Real Elvis Presley?’, BBC Culture, 27 June 2022, archived at <https://web.archive.org/web/20220626231952/https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20220624-who-was-the-real-elvis-presley>, accessed 26 July 2022. |

| 27 | Robert Daniels, ‘Elvis’, RogerEbert.com, 22 June 2022, <https://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/elvis-movie-review-2022>, accessed 16 July 2022. |

| 28 | Luhrmann, quoted in Bergeson, op. cit. |

| 29 | At the time of writing, Elvis had made over US$276 million in box office receipts globally. See Andrew Korpan, ‘Elvis Global Box Office Crosses $276 Million’, Collider, 28 August 2022, <https://collider.com/elvis-movie-276-million-global-box-office/>, accessed 14 September 2022. |

| 30 | Two of the most globally publicised social issues to emerge from the United States in recent years have been police violence against African-Americans (and the associated Black Lives Matter movement), and the overturning of the US Supreme Court’s 1973 Roe v. Wade ruling, which has removed barriers to abortion being made illegal in many states. See Leah Asmelash, ‘How Black Lives Matter Went from a Hashtag to a Global Rallying Cry’, CNN, 26 July 2020, <https://edition.cnn.com/2020/07/26/us/black-lives-matter-explainer-trnd/index.html>; and Nina Totenberg & Sarah McCammon, ‘Supreme Court Overturns Roe v. Wade, Ending Right to Abortion Upheld for Decades’, NPR, updated 24 June 2022, <https://www.npr.org/2022/06/24/1102305878/supreme-court-abortion-roe-v-wade-decision-overturn>, both accessed 15 August 2022. |