You are a writer, director, and producer … those roles in film production are often conflicting. Is it easier for you to wear two or more ‘hats’ on a production?

Yes it is much easier because for me they’re not in conflict, and if I’m doing all three then all three are working towards the same end. They’re in harmony with each other, so that a small creative decision on set is better informed by the fact that I know exactly what the budget is doing. The fact that I have done the schedule means I can take things into consideration which have to do with what I’m intending to do with performance.

Which of those skills came first? Did you always want to be a director?

It’s not so much ‘always wanted to be’ … I didn’t know much about the differentiation of the roles when I applied to go to the Australian Film & Television school. I applied for the Production Workshop, which included production, sound, camera and editing for the 3 years, so you learnt all the disciplines and everyone got to direct a film … my education was very rounded.

You acquired a palette of skills …

Yes, and it developed … the writing developed last, I never thought that I could write, but it developed as well.

Did you watch a lot of films?

Yes we had courses on the history of cinema and we went to the film festivals … that was considered to be terribly important.

What memories do you have of the films you saw then?

It was really going through a history of cinema from the beginning and getting an appreciation that cinema was much deeper than just making a film and hoping a lot of people would go and see it. I remember specific films and a political awakening through films like Novecento.

Is the high level of independence you represent important to you or has it been forced upon you?

It’s something that developed through experiences that I had and sort of stumbled into as well and that I have now come to love. When I first made films I thought I had a career trajectory, you think in those terms, and each of the first three films that I made has some value, and they got quite interesting reviews, and for quite different reasons each ended up in distribution hell. The third one was formative in the sense that the process of making it was terribly, terribly difficult – and there were lost friendships and shattered dreams, and yet it was a credible film and still ended up in distribution hell.

This was Dingo …

Yes, Dingo … It made me think about things … the film was not at all bad, but there were shattered dreams, and the film is nowhere. So what have I achieved? Nothing. From that point I began to look at ‘process’, I thought, if a film takes a year to make, and the process is no good, you could well end up with nothing. But if the process is terrific then you’re living a terrific life. So I began to make films for myself, and I cared zilch about the career trajectory, I cared only about the film. I husbanded the process, and (laughs) from that point I tended to be much more successful.

It meant that a film like Epsilon, which is quite flawed, but which threatened to be an interesting success, disappeared almost completely for the most astonishing reasons, it’s effectively locked up in vaults. I’m quite OK with that because the process of making it for us all was so fantastic that it can never be taken away from me. I know what’s wrong and right about the film, but that’s the film, and nothing can change it.

You’ve done a range of films which cover a range of genres … is that a deliberate professional choice or do you come upon a story and say ‘yes’ to it regardless of its genre?

I think it’s quite complicated. One of the factors is in the process – if a film is too much like something else then it becomes the same. If you repeat something too often it becomes like a job. Making films is too hard for it to be a job. If I wanted job I’d do something a lot easier. I think what interests me at any particular time is something that I haven’t done before, that makes it interesting, and the other fact is that when you have a particular story then I consider it quite a separate piece to anything I’ve done before and my way of thinking is ‘how can I do this to best communicate this particular story or concept’?

The Tracker, your new film which opened the MIFF, is based on a story set in 1922 … where did the story come from?

I made it up. It came about through two things. One was the week on the Dingo shoot, when with a reduced crew and cast we shot in the Kimberley ranges. All we had was a steady-cam, no lights, and it was by far the most pleasurable week of Dingo. It was also disproportionately valuable in terms of what it gave to the film and what it cost, it was by far the cheapest week of the shoot. We camped outside and slept under the stars and it was fantastic, and the thought of making a whole film like that was very attractive.

That was the superstructure. In the meantime I was doing research into another project which I had been commissioned to write, and ultimately to direct, and it was a ‘first contact’ story. There’s not much written about first contact, so I was reading quite widely and coming across all sorts of material and the two things together coagulated into a story which I wrote in 1991.

Is The Tracker the story of a journey or a chase for the characters?

It’s a journey … it’s meant to be a chase but it’s not really.

What interests you about journey stories?

That aspect is not so interesting for me, but what does interest m e is the people and how they respond to things … the human side.

Can you talk about the paintings by Peter Coad that are inserted into the film instead of moving images?

I was trying to work out what to do with the violence in the film. When I’d written it in 1991 I had described the violence quite graphically, and in m y mind it was always graphic – but at the same time we don’t know much about screen violence though we have a fair idea it isn’t good. It gets harder and harder to have an effect if the bar is raised on depictions of screen violence … each time you have to be tougher and tougher and you try to find interesting ways to splatter people across the screen, and so I thought ‘how do I do this?’ Peter Coad is an artist that I know, and over the years I’ve thought if there was a way we could work together… and one day he was visiting and as he was walking across the road from his car I thought, that’s it!. So he came out on location with us for 4 weeks, doing studies, and we collaborated on how the paintings should look in the film. It was quite a process and it works much better than most people expected. By that I mean the people who were involved in some way in putting up the money for the film. They were quite concerned and there were many exhalations to shoot the material anyway.

Just in case …

Yes, just in case, but to me it was wasting money and time, but when the paintings went in they melded beautifully and they’ve become a really interesting part of the film.

Why do you think Australian films haven’t confronted this level of violence that you have included in The Tracker, especially when you think back to films like The Chant of Jimmy Blacksmith which was at its time very confronting?

It was a fine film, a film that everybody expected to do well, and in its day wasn’t cheap, and it failed at the box office. It got terrific reviews but failed. And from that point on it became conventional distributor wisdom that these sorts of film don’t work, and so films like this become much more difficult to finance.

Do you think that distributors see a clear division between entertainment and political issues such as those depicted in The Tracker?

I think it depends on the consciousness of what is political. Spiderman is quite political. Any mainstream American film is as political as anything I do because they create a depiction of life according to certain principles, and that becomes part of a way of thinking. Now if we’re talking about films that are overtly political, well for me the first thing I ask is, why would I want to see this film, and is it entertaining to me? The answer has to be ‘yes’ before I get interested, and what I consider to be entertainment is to be made to feel something, whether it be laughter or passion or beauty, and for me Novecento is a very political film yet it’s also the most wondrous entertainment imaginable. It really depends on the film … I’m writing a comedy at the moment and the only raison d’etre it has is to make people laugh, or to make me laugh!

Which leads me to the last question, what’s the next project?

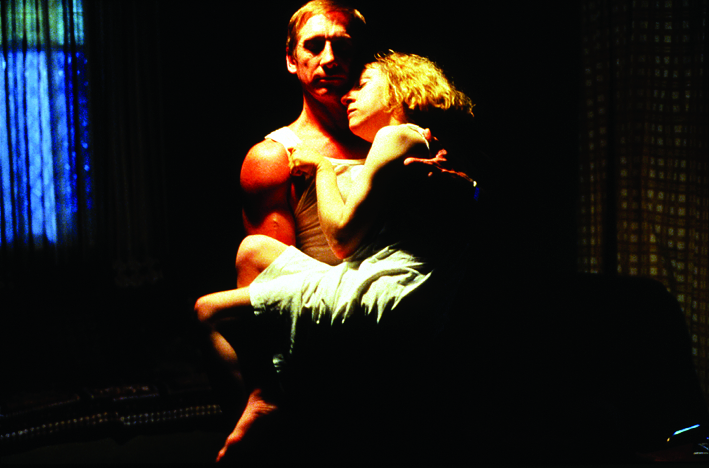

I don’t know what’s next. I’m writing the comedy but it will take a long time, and I’m in post production on another film, called Alexandra’s Project, which is a psycho-sexual mystery thriller about the politics of sex and marriage.