Paul Cox is something of a paradox among Australian film makers: a director who harbours a deep contempt for worldly success, yet whose own directorial efforts have become almost synonymous with the reviving fortunes of the Australian cinema in recent years.

Since his arrival on the local film scene in 1977, Cox has become one of the mainstream feature film industry’s most trenchant critics, championing a personal and humanistic approach to film making.

Cox was born in Holland 45 years ago, and settled in Australia in his mid-20s. He slipped into feature film making almost by accident, after enjoying some success as a still photographer. And after several years of making experimental and documentary films and teaching.

His first 35mm feature, Inside Looking Out, an account of disintegrating marriage, was completed in 1977, for just under $50,000. Kostas, a love story about a Greek journalist and an Australian woman, followed two years later.

Then, in 1982, came the breakthrough of Lonely Hearts. This charming love story about a shy middle-aged couple firmly established Cox’s reputation here and abroad.

Lonely Hearts was followed in 1983 by Man of Flowers, a portrait of a wealthy, middle-aged man who is emotionally and sexually unfulfilled, and by My First Wife, a probing family drama which was shown in Australian cinemas last year.

Perhaps a good place to start is with your new project, Paperboy, for the Australian Children’s Television Foundation. What’s it about?

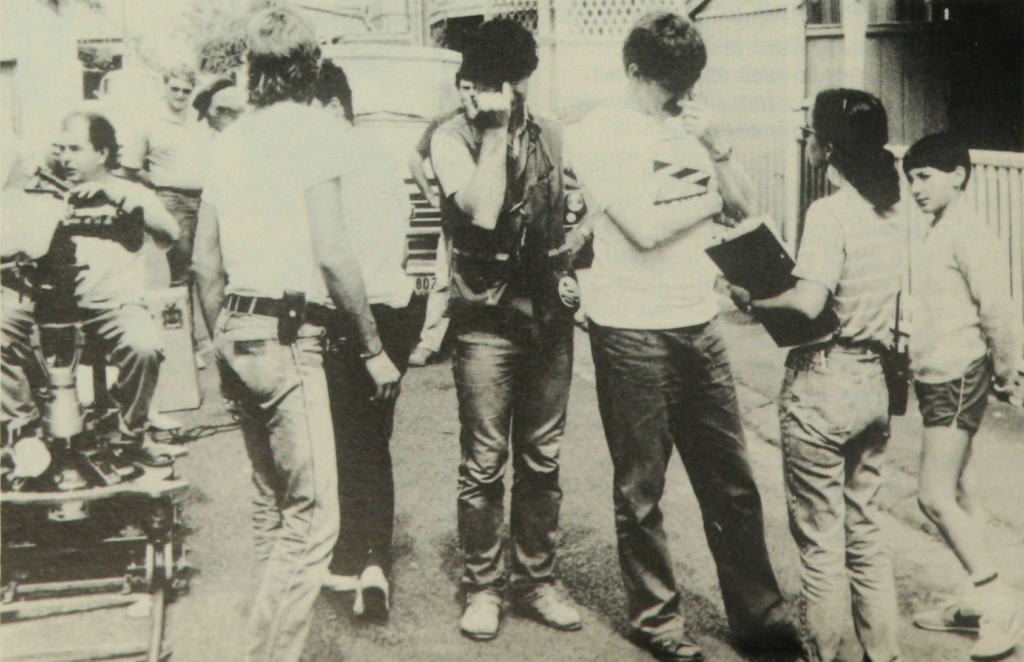

It’s the first time I’ve done anything for television. But that’s really a crazy expression, “doing something for television”. I find it quite puzzling when people say, “this is for cinema or this is for television”. What the hell difference does it make? Most films finish up on television anyway. I think if they put a bit more care into what is on television, television would be used more properly. It’s about the Depression in the 1930s. The father suddenly gets the sack and his son goes out and gets a job and tries to support the family. He fights with his father, runs away from home, lives with tramps in the street. He comes to terms with the world outside and there’s a happy ending. It’s very much for children, but I think it should appeal to adults too.

Were you conscious that you were making a film for a young audience? Did you have to be more careful, more simplistic?

No, I feel most children’s films are patronising. I hope this one doesn’t patronise children at all.

Your feature films have been on adult themes and now you’ve been working for children. Do you feel that these two areas of film making sit comfortably together?

I’ve always remained a child. I make films because I get puzzled about the way we grow up and get thrown together; I observe it and make films about it.

Are you working on any other projects now?

I have a long-term project going – a film on Vincent van Gogh, all done from his point of view, without ever seeing him. You see all the people he saw, all the things he went through.

Then in November I’m making a feature film shot partly in France and partly here. It’s not a domestic drama like the others. It’s a love story about two blind people who teach each other how to see.

I’m also considering some offers to work in the United States. There are one or two I’d like to look at. It would be nice not to have constant financial worries because I don’t make much money out of my films. I’m seriously looking at one through a subsidiary of 20th Century Fox – that’s not a very large one. I’m not saying arrogantly it must be done on my terms, but with the horror stories coming out of Hollywood … I don’t need to experience that.

What then would be the main consideration in going to America?

Somewhere in the back of my mind there is the preacher, the silent desperation about the world; if I can make people think or feel or remember then I have succeeded as a human being to make them remember their own little humanity. The more I can do that the more I will feel fulfilled, it’s not some sort of ambitious thing.

If I can make this particular film in the States – it’s a very dramatic piece – I will reach out very far and that’s the only thing I can do about living in a time when we can be just blown off the map tomorrow. It’s pathetic. That’s the anger I try to express in what I do. People say to me, “why don’t you make political films?” I think my films are extremely political because they are about human beings.

Is Melbourne and Australia still stimulating enough for you? Does it offer enough scope for you?

We shot nearly the whole Paperboy film around the office here, the back lane. I don’t have to go very far! [Laughter.] I think in one way I feel slightly protected here. There is still some sort of pioneering situation here.

You need a base, a home, which happens to be here. I’ve kept very sentimental about home and this has become my home. I don’t feel at home but I wouldn’t any place else either. It’s one of those magic contradictions!

How did you become involved in film making?

I made films as a hobby, on Super 8 and 16mm. Then, because the Photography Department at Prahran (College of Advanced Education) where I taught, needed someone to teach cinema, I started to teach film making, without knowing all that much about it. It grew from there.

Teaching was very good because I had to become an editor, a script writer and cameraman. I did everything myself, and it helps greatly now because I have an understanding of those processes.

Did you ever want to be a “film director”?

No. I was a compulsive film maker who slowly became a film director. I never started making films out of any great ambition. It just happened. It rolled on and now it’s become quite dangerously large. I did it out of some strange conviction and compulsion. Certainly, not to make a career. When people ask me, today, what I do, I say, “I am a film maker”. Film director is way over the top!

Some of your early films are often described as experimental and abstract films. Where they the natural outgrowth of your interest in still photography?

I found photography very limiting, I had come to the end. I looked back at my very first photograph and found it was still my best. With a lot of photographs I took after that, I had quite a lot of success – they went all over the place – but they did not have much to say. And so my first photograph is still hanging over there; it’s the best one because it’s simple, direct and it’s got a strange sense of composition.

Why did you stop making shorts and experimental films?

Nobody would look at them! With a short, you would spend all your money on it, show it to a few friends and it ended up on a shelf.

When I did Island I worked on it for six months, day and night – a ten minute film – what for? It ruined my life; I was totally engrossed; it fired at me; it was spitting something from the past at me. There’s maybe a thousand little tricks in that film, all adding up to whatever, because I don’t understand it anymore myself. I understood it very well at the time!

But still, when I show that film, it has a hypnotic quality you can’t possibly just walk away from. The end of that six months, which were absolutely horrendous, I think that’s when I became a film maker. The amazing potential of the medium was just staggering!

I feel I must have been experimenting to give form and shape to the psyche. You’ll find it very strong in Man of Flowers and also in My First Wife. The short films must have been, subconsciously, a learning ground for all this. I was far too fascinated with images, I just wanted the actor or actress to do what they had to and get off the screen so I could get on with the film. Then suddenly it changed and I became very aware of what the actors were doing. In one way I’m pleased that that happened later on because the early experience is very useful now.

How hard was it to make your first feature, Inside Looking Out?

One tends to forget the nonsense you go through.

Was it difficult raising the budgets for your first features and convincing the various government film corporations to support your efforts?

Almost impossible. Australia’s glowing little fire that was to slowly become a film industry was in no way ready to accept a crazy foreigner running around with very personal, so-called “European” ideas.

Many producers had, and still have, a totally imported attitude to the making of their films. Instead of inventing their own language and their own cinema, they imitated the Americans above all, straight away. Also they had to go through the historical thing, making films about their own history to give them more identity. I had enough identity, I didn’t need that! [Laughter.]

How important was the success of Lonely Hearts for you, particularly in America?

I think the success of Kostas, which preceded it, was underrated. It got a bit of a beating here but it did very well overseas, especially in Europe, where it was sold to several television stations. So that already set some sort of pattern for Lonely Hearts which, once again, was produced with great difficulty.

Lonely Hearts was the first time I was “produced”. I’m a free person, I don’t wished to be produced by anybody, certainly not by people who are not concerned about the actual film, only about their egos. You certainly cannot make films by committee. I learned from Lonely Hearts to always be my own producer.

There was a lot of reaction to Lonely Hearts in the States – like, “this film restores the cinema to the adults”. Most thinking, feeling, struggling people don’t go to the cinema anymore unless there is a special film in town. It brought a lot of people back, especially in the States; that was its greatest merit. Also, they realised you can make films about little people.

One of the things I like about the States is its movie-going public – people know about movies, it’s part of their lives. It’s not like that here you know.

You’ve had a very successful working relationship with actor Norman Kaye.

He is a very fine collaborator. We grew together. I remember someone from Cinema Papers asked me, “What are the qualities you see in Norman Kaye as an actor?” I said that his qualities as a human being are far more important, everything else follows.

Man of Flowers was an extraordinary experience; we were all totally exhausted by it. We had to be insane to make it because first of all, there was no money. Secondly, it was a very thin script. I knew that in three weeks, for that amount of money, with everything we wanted to do, you couldn’t make a feature film. Yet we did, with the help of some very fine people. When you follow the success of Man of Flowers around the world, it’s unbelievable. If anyone had reasoned about the film, it wouldn’t have been made. It must be some sort of madness. But I would do it very gladly again.

Have you found the film corporations more responsive to your work now?

Of course. Film Victoria has been very good now.

Does it surprise you that almost overnight you’ve become a mainstream, bankable director?

I’m very responsible. I find that important when you are playing with so much money. As soon as you hit $100,000 it doesn’t matter whether it’s a million dollars or ten million, it’s all lunacy.

I think it is appalling that in Australia, with a population of 15 million, they still talk about two or three million dollars as a low-budget picture. Any other country that has two or three times the people would call one million dollars a reasonable budget film.

My First Wife, my largest budget, cost $690,000, we came under budget, but it certainly looks like a very grand film. Nobody was underpaid, everyone was paid splendidly, more than on the other films.

Have you been influenced much by other film makers?

I like some of the early French directors like Cocteau and Vigo. And I still have a great deal of respect for Bergman. I find it amazing that someone who goes that far can suddenly go out of fashion.

Do you see any similarities between your films and those of other directors?

Nobody can claim to be an auteur as such; everything rubs off. One film which did influence me very much, though, was Claude Goretta’s The Lacemaker. It gave me courage, not because of its style or anything like that, but because it successfully realised an idea, a kind of approach to film making, that I’d been thrown out of offices for proposing in Australia, and told I was a wanker. The Lacemaker moved me very deeply; I realised that people were starving for a bit of humanity. It’s so simple. And of course, I was right … he says arrogantly! But I was right.

How much creative control do you have over your films?

Absolute. At this stage, for me to go into a situation where I don’t have final say would be ridiculous. I fought for this for so long. I’m not that stupid not to listen when somebody has proper suggestions. But I refuse to be put into a harness before I start to move.

Unfortunately, it’s become standard procedure that “final cut” is in the hands of the producer, not the director. Who are these producers? They don’t make the films; where does their knowledge come from? Hardly any of them ever read a book. And they don’t read scripts, they read synopses. These are the people who then engage someone to pour his heart out, to make a film and then say, “Cut here, cut there”. I don’t know of anyone else in Australia who insists on the degree of artistic control that I do.

If this film in the States comes off, of course that will be the very first question that comes up.

Do you improvise much on the set, is there enough flexibility for that?

I think people who don’t do that are not film makers. I think you make a film “in the making”. It’s absolute lunacy to have to sign every page of script and translate it onto film. My films are always better than my scripts.

I do have great faith in the actors. I always need and want the right to change the script when a word does not suit them. I also find that when you know somebody’s strengths and limitations it is much better to work within that than go get another person. But I do think it works on trust. If an actor or an actress doesn’t trust you, or can’t get totally into the script or the film, it is pointless to proceed. They have to have faith in you.

Within the film industry, you’re often described as the “champion of the personal film” …

It has something to do with using some of your own life, your own deeper thoughts and silences and putting them onto film. Within every individual there are so many darker, deeper grounds that are rarely explored, that we are conditioned to ignore and neglect. They are what can make us so very rich. Whether they are positive or negative grounds, I don’t care. To stir those a little is my aim.

Obviously relationships are important to you. All of your feature films deal in some way with the relationship of a couple.

I think despite the fact that we behave very badly at times, we are the only species on this planet who can exchange emotions. And have feelings. I used to really dwell on that, I don’t anymore. I had a very grim background but I had a very loving mother. She gave me a constant belief that in spite of everything people are good and I’m very grateful to her for that.

In the States they asked me once, in front of a lot of other people, whether I had a mother complex. I didn’t know what to say. Suddenly I turned around and said, “Well, is there one man here who has not got a mother complex?” Nobody raised their hands.

The screenings of My First Wife were very traumatic to a lot of people in the States because there, even more so than here, so many people have gone through (breakups). And this whole idea of making the man weaker is, in a way, very American. But it wasn’t done consciously.

My own world at the moment embarrasses me. I find it very embarrassing to suddenly be somebody. I didn’t do any interviews for a long time. But there are a lot of things you can say that you never had a chance to before.

Sometimes when I hear myself talk, I think, what an egomaniac! I can assure you it’s not like that at all. I go through absolute amazing hell.

When I’m making a film, I detest it. It’s a dreadful time. I get so involved. If in the end it takes too long, you just get physically exhausted. It’s constantly at you, it’s alive! For a few days it’s a very exciting process, then it drains you. I wish someone else could teach me how to do it.