The Gothic novel seeks an epistemology of the depths; it is fascinated by what lies hidden in the dungeon and the sepulcher. It sounds the depths, bringing to violent light and enactment the forces hidden and entrapped there.

— Peter Brooks[1]Peter Brooks, The Melodramatic Imagination. Balzac, Henry James, Melodrama, and the Mode of Excess, Yale University Press, 1976, p. 19.

The credits at the end of John Hillcoat’s recent drama To Have and To Hold includes the following acknowledgment: ‘Storm footage by Simon Kerwin Carroll’. Hillcoat subsequently confirmed, in an interview with Paul Harris, that a company was specifically commissioned to shoot footage of a tropical storm. Why? The footage was not used to advance the story and could have easily been deleted as it occupies only a brief moment in the overall film. This brief moment is indicative of a cinematic style that contains a narrative voice not content to describe and merely record reality, but constantly applies pressure to the surface of reality so that it will yield more than is normally found in Australian films. This ‘excessive’ style should not, however, be confused with what director Stephan Elliott describes as the ‘in-your-face filmmaking’ cycle that has characterized recent Australian films such as The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert (1994) and Bad Boy Bubby (1993) where excess remains on the surface in the form of costume, setting, performance and situation.

The excessive presentation in To Have and To Hold is restrained by the selection of dramatic mode and follows a disciplined, controlled pattern of escalation. The selection of a storm sequence, its presentation and placement in the narrative sequence, reveals a knowledge of aesthetic traditions and a sense that the filmmakers are, like the Hollywood craftsmen of the 1940s, aware of the significance of melodrama as a ‘heightened and hyperbolic drama, making reference to pure and polar concepts of darkness and light, salvation and damnation’.[2]Peter Brooks, p. ix. The brief reference to the storm, marking the last phase of the drama, takes us to the core of melodrama, a dramaturgy based on the play of ethical signs.

Aside from brief excursions into what Karl Quinn describes as ‘suburban surreal’ in films such as Strictly Ballroom (1992), Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert and Muriel’s Wedding (1994)[3]See Karl Quinn, “Drag, Dags and the Suburban Surreal”, Metro, Summer 1994/95., the Australian cinema, at least since its renaissance in the early 1970s, has rarely deviated from what could be kindly described as a kind of ‘poetic realism’, a cinematic form described by Adrian Martin as an ‘odd zone somewhat between naturalistic drama and the ‘tall tale’, a style that’s a mutation of the ‘poetic realism’ that surges and falls away throughout international cinema, based on a fond (and oh-so-slightly ‘fabulated’) observation of everyday life’[4]Adrian Martin, “More Than Muriel”, Sight and Sound, June 1995, p. 32.. Rarely has the Australian cinema displayed interest in, or knowledge of, those dramatic forms, such as melodrama and the Gothic, which assumes that nature is ‘primed to produce things beyond its phenomenological appearances’.[5]Peter Brooks, “Virtue and Terror: The Monk”, English Literary History, Summer 1973, p. 255.

To Have and To Hold was inspired by a trip director John Hillcoat took with his sister to Papua New Guinea some 10 years ago. The desire to wed the dramatic excesses of melodrama with life in Papua New Guinea emerged from Hillcoat’s fascination with the extremes in all levels of life: ‘What lodged in my mind was the heightened reality of the way people live, the light, the contrasts, the heat, the sound, the insects … all the sensory things. These are the ingredients which can help make powerful drama’. On the other hand, screenwriter Gene Conkie, after viewing Wake in Fright (1971), a film which shares many similarities with To Have and To Hold, was intrigued by Wake in Fright’s fascination with the ‘notion of ‘evil hallucination’ and the ‘strange implications of obsessive behaviour’. This provoked Conkie into exploring the possibilities of a tropical climate to heighten a story of romantic obsession based on a situation where two people with conflicting aims project their intense desires onto the other person.

Two Alfred Hitchcock films, Rebecca (1940) and Vertigo (1958), provided the direct inspiration for To Have and To Hold. The basic story concerns Jack (French actor Tcheky Karyo), an expatriate living in New Guinea who is distressed by the recent loss of his wife Rose. Two years after her death he visits Melbourne where he is attracted to a young writer of romantic fiction. Initially she captures his attention during a reading from her recent novel (“Seduction in the Snow”). Significantly, the woman is wearing a red dress. After a brief romance in Melbourne, Jack persuades the woman, Kate (Rachel Griffiths), to return with him to his remote house on the Sepik River. Kate, however, soon realizes that Jack is obsessed by the memory of Rose, and gradually the artificiality of her fantasy life in a ‘tropical paradise’ with a ‘sensuous’ Frenchman is destroyed by his aberrant behaviour. Jack’s excesses are intensified by videotape of his wife drunkenly performing for another expatriate, Sal (Steve Jacobs). The situation is also heightened by the mysterious presence of Luther (Robert Kunsa), a Papuan who was seemingly involved in Rose’s death.

Melodrama developed as an emotional and ethical drama based on the Manichæist struggle of good with evil in France in the late 18th century. Hillcoat and Conkie were able to adapt its basic tenets to a specific historical context – namely contemporary European exploitation of Papua New Guinea. Hillcoat’s choice of dramatic mode emanated from his belief that:

[The] genre of melodrama explores personal dynamics in a domestic setting which are very loaded and strong metaphors for bigger situations. There is an allusion to the exploitative nature of colonialism – the old world projecting its desires onto the culture of a new world country, but also, like the classic films of the ’40s and ’50s, this film takes people’s psychological obsessions and puts them under the microscope. I set out deliberately to use a lot of those genre traditions but in an unusual, contemporary setting.

Hillcoat cites Rebecca as a key influence on his film and this establishes not only melodrama but also a parallel dramatic mode, the Gothic, as a significant structural influence on his film. The Gothic developed at the same time as melodrama in the late 18th century and both modes share many characteristics. Both, for example, were reactions to the ‘pretensions of rationalism’[6]Peter Brooks, The Melodramatic Imagination, p. 17., which may help explain the cool response to To Have and To Hold by the Australian critical establishment. The distinctive tone of the Gothic emotion is embodied in this passage from Matthew Gregory Lewis’ The Monk (1796):

While I sat upon a broken ridge of the hill, the stillness of the scene inspired me with melancholy ideas not altogether unpleasing. The castle, which stood full in my sight, formed an object equally awful and picturesque. Its ponderous walls, tinged by the moon with solemn brightness, its old and partly ruined towers, lifting themselves into the clouds, and seeming to frown on the plains around them; its lofty battlements, overgrown with ivy; and folding gates, expanding in honour of the visionary inhabitant, made me sensible of a sad and reverential horror.[7]Peter Brooks, “Virtue and Terror”, p. 255.

This mixture of pleasure and awe, combined with ‘the delectation of the chiaroscuro’[8]Peter Brooks, p. 255. and an excessive presentational mode, clearly signified the ‘presence in the world of forces which cannot be accounted for by the daylight self and the self-sufficient mind’.[9]Peter Brooks, p. 249. As in melodrama, Gothic fiction follows the ‘logic of the excluded middle’.[10]Peter Brooks, The Melodramatic Imagination, p. 18. Characters are placed in extreme situations in extreme settings – notably areas of ‘forbidden’ space such as dungeons, crenellations, spiralling staircases and concealed doors – which, in effect, represent the literal manifestation of desires that are constrained and repressed. The Gothic, like melodrama, is not concerned with complexity of characterization, but with an ethical drama as virtue struggles to break through the nightmare condition that is repressing it.

Melodrama and the Gothic differ in their faith in the ability of humanity to transcend its obstacles – melodrama in this regard is more optimistic than the Gothic which normally displays little or no faith in the ability of people to transcend or transform their everyday world. This pessimism produces a situation at the point of closure where the protagonists are ultimately ‘caught in paradox, ambiguity, conflict and contradiction’.[11]Peter Brooks, “Virtue and Terror”, p. 253. Gothic fiction is also a more confronting form than melodrama given that terror and anxiety subsume the everyday in a world where the sacred, the domain of ethical values, is no longer evident or even acknowledged. What remains is a ‘terrifying and essentially uncontrollable network of violent primitive forces and desires’.[12]Peter Brooks, p. 262.

The traditional Gothic world of dungeons, attics and other forbidden places is cleverly transformed by Hillcoat in To Have and To Hold through his mise-en-scène. Colour tones (noticeably red and garish greens and oranges in the interior scenes) combine with subtle compositions, bravado camera movements and a particularly effective use of sound to detail the gradual disintegration of Jack’s mind and Kate’s world. A recurring visual motif combines the image of machinery – fans, generators, and funshow equipment – with the aural shifts in intensity in various scenes. For example, the threatening sound of insects escalates as Kate gradually realizes the extent of her entrapment.

The importance of sound was acknowledged by the film’s producer Denise Patience: ‘There was a complicated plan for sound design so that as the audience goes deeper and deeper in the film, the soundtrack expands and gets deeper and deeper as well. By the end of the film the noises of the tropics are constant … birds, frogs, cicadas’. Similarly cinematographer Andrew de Groot, production designer Chris Kennedy and director John Hillcoat carefully planned the colours for the film – the erotic, obsessional implications of the red dress, as red becomes a recurrent tone in many scenes, especially at the end of the film, together with the greens of the jungle which take over Jack’s house towards the end.

To Have and To Hold subsumes a postcolonial critique into its dramatic fabric. This aspect was reinforced by Hillcoat’s experiences in Papua New Guinea where, in a recent interview, he cited bizarre examples of European behaviour – from the mildly exclusive golf courses carved out of the jungle to the training of dogs which only attack black flesh. This critique reappears in the film in the characterization of Jack and Sal. Jack exploits the local youths through illegal screenings of Van Damme, Jimmy Clift and Bruce Lee movies and their violence is emulated by the local gangs, whilst Sal makes his living through poaching and selling beer. His attitude is personified by his comment to a young PNG boy: ‘Go on, piss off and go climb a tree or something’.

These, however, are only superficial manifestations of post-colonial behaviour as its critique is built into the dramatic structure. The expatriates are shown to be perverse, insane and corrupt whilst the PNG people working and living near Jack are representations of wisdom and virtue. This binary premise is worked through the central enigma concerning Rose’s death. Luther, the PNG youth befriended by Kate, becomes the scapegoat for her death in the boat, although he is vindicated at the end of the film when a video shows that Rose died as a result of Jack’s jealousy. Jack, however, abandons Luther who is imprisoned where he loses his left eye. Luther also becomes Kate’s saviour and the means by which she escapes back to Melbourne.

The most effective symbolic representation of European exploitation is reserved for the final moments in the film. In a scene reminiscent of the perversities of the Southern slave-owners in Mandingo (1975), Jack employs a PNG woman to wear Rose’s red dress and sing the Bob Dylan song “I Threw It All Away”. This song, with a new romantic arrangement sung by Scott Walker, is combined with the red dress as the two dominant symbols throughout the film. Each is used to signify the traditional Gothic motif of erotic desires mutating through denial into perversity.

The song is first heard as Jack pauses outside the bookshop in Melbourne when he sees Kate (in her red dress). Later Rose, on videotape, uses the song and the dress to humiliate Jack. When Kate finally agrees to wear Rose’s red dress Scott Walker’s voice is quietly heard in the background. At this point there occurs an effective shift in aural intensity indicating the extent of Jack’s dementia as Scott Walker’s voice shifts from the background to the foreground. A similar shift occurs at the end of the film when the PNG woman’s voice is gradually overpowered by Scott Walker’s version. In both cases Scott Walker’s dominance of the soundtrack indicates the replacement of reality by fantasy and madness.

In the latter scene, the madness reflected in Jack’s perverse desires, is associated with expatriate exploitation. Unlike Kate who is able to escape to Melbourne (she is shown on the television set behind Jack), the PNG woman cannot get away so easily. As the woman sings, and Scott Walker is heard, the camera’s attention shifts to Jack as he holds up a glass of red liquid. Tcheky Karyo’s face, the resultant red glow and Scott Walker’s voice combine to conclude the film with a powerful anti-colonial image, an image which has been foreshadowed throughout the film and that emerges from the dramatic fabric rather than tacked on.

Melodrama and Gothic structures are interwoven throughout the film as the two central characters represent each mode. Kate lives in a world of melodrama and her simple romantic prose is used as an ironic counterpoint to Jack’s Gothic world. Kate’s world assumes that love will transcend all, that her desire will ‘save’ Jack from his demons. During the first reading in the bookshop her fantasy is clearly outlined:

He appeared and the snow melted. He was woven from the fabric of her darkest dreams. It was as if she had been dead for years and now she was finally alive.

Kate’s world, as the film makes clear, is of misguided fantasy, and even during her first reading the lighting subverts her romantic prose as it shifts from a romantic blue hue to a dark background – motivated by a slow dissolve from the bookshop to the next scene. Similarly, as Jack and Kate dance in front of a brightly-coloured spinning wheel during their whirlwind courtship in Melbourne, the camera foreshadows the horror ahead as it obsessively dollies around the couple in a scene strongly reminiscent of James Stewart’s orgasmic kiss with Kim Novak in the stable in Vertigo, a film which both director Hillcoat and screenwriter Gene Conkie cite as a strong influence on To Have and To Hold.

Hillcoat’s film is structured according to a series of repetitions –events, dialogue, colour patterns, camera movements, composition, objects (such as the use of shutters in Jack’s house to signify Kate’s entrapment) and musical motifs – each referring to the inevitability of the violent climax. For example, the spinning wheel of their courtship period transforms into an overhead fan during their dance in the Sepik River house. Motors regularly grind to a halt at the end of scenes and crucial lines of dialogue (‘this is fucking pathetic’) reappear at pivotal moments. Hillcoat’s strongly expressive technique impressed Tcheky Karyo: ‘Making the movie I was aware that he didn’t keep the camera right there on you. He allows the camera to tell a story by the way it moves, by playing with the focus and framing’.

Kate’s romantic voice-over is ironically counterpointed at each stage in the film. Recording her hopes as she arrives at the Sepik river home for the first time (‘She knew she was stepping into a forbidden world’), the relatively conventional presentation of Kate’s entrance, point-of-view shots of the house inter-cut with her reaction, ends with a bravado camera movement as it swirls up to the fan. accompanied by a sudden increase in the noise of the fan. Later, prior to Jack offering her the red dress, Kate’s voice-over indicates the gap between his reality and her fantasy: ‘there was a swelling mystery beneath his calm surface as the swirling current drew her ever closer to him. She loved his moonlight and the black places in his heart’.

Eventually, Jack’s aberrant behaviour, combined with the onset of malaria, breaks through Kate’s fantasy world and her voiceover only serves to emphasize the horror of her situation. This climaxes with a medium shot of Kate at her computer as she begins narrating Chapter Thirteen of her novel “Jungle of Love”:

The sky was black and velvet and the stars were distant diamonds you could reach out for but never reach [Jack appears behind Kate]. There were insects that laid eggs under your skin and then they hatched. [Insert of the computer screen showing the beginning of an insect invasion under the screen. Close-up of Kate showing that she clearly is sick]. But only his touch was real … [Jack’s hand is shown roughly stroking her throat before moving on to her breast] … the velvet touch that made her flesh shiver.

Jack pulls her to the floor, drops his pants and has sexual intercourse with her despite the fact she is clearly not well. Hillcoat emphasizes the extent of this violation with an insert of the black insects engulfing the computer screen.

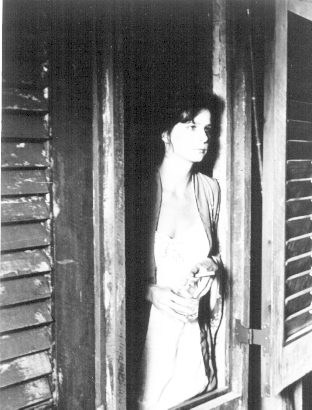

This scene begins a sequence which, collectively, functions as the primal scene in theatrical melodrama – evil’s moment of spectacular power where innocence cannot speak its name and is left stunned and humiliated.[13]Peter Brooks, The Melodramatic Imagination, p. 34. Suffering from malaria and without her passport, Kate tries to get out of the house by suggesting they take a holiday. Jack, drunk with a gun in his hand, is aware that she wants to leave him. This nightmare sequence concludes with Kate waking one morning and finding that Jack has dressed her in Rose’s red dress. Through the shutters of her bedroom window she notices the police talking to Jack by the river. However, when she approaches the police her plea for help is ignored as Jack calls her Rose and slaps her to the ground.

The primal scene in melodrama always represents the low point of the drama and Kate immediately signifies her process of renewal by, first, ripping the red dress away from her body and then cutting her hair so that it cannot be made into a ponytail by Jack to replicate Rose’s hairstyle. Aware that Jack’s illness has progressed to a point where he cannot differentiate her from his dead wife, Kate confirms she (Kate as Rose) was having a sexual relationship with Sal. To reinforce this identification she repeats the words uttered by Rose when Jack confronted her with his suspicions – ‘this is fucking pathetic’. Desperate to survive, Kate becomes complicit in Sal’s murder.

There is, however, an interesting foreshadowing of this process earlier in the film when, in an attempt to rekindle Jack’s sexual desire, Kate begins playfully reminding him of ways in which she (Kate) resembles Rose. This has the effect of invoking Kate as a contributing factor in Jack’s condition. However, it would be wrong to make too much of this incident since in all other respects Kate is the classic masochistic Gothic heroine waiting for the dark, mysterious stranger to fulfil her romantic fantasies and sweep her away to an exotic setting.[14]See, for example, Suspicion, Rebecca, Gaslight (both American and British versions – 1944 and 1940), Jane Eyre (1944), I Walked With A Zombie (1943), Dragonwyck (1946) and Secret Beyond the Door (1948).

Except for Andrew de Groot’s cinematography (which failed to win), To Have and To Hold was ignored at the recent AFI awards. It is disappointing the technical prowess of Chris Kennedy’s recreation of a Sepik River village at Babinda on the Russell River in North Queensland, and the film’s magnificent score by Blixa Bargeld, Nick Cave and Mick Harvey, did not receive the credit deserved and indicates the structural limitations of an awards system that is sufficiently beguiled to award virtually every category to the same film (Shine).

To Have and To Hold was not a commercial success in Melbourne. Local critics such as Barbara Creed and Adrian Martin were less than enthusiastic and, given its target audience and distribution pattern, newspaper support was essential. The most extensive critique of the film was by Robert Nery in Cinema Papers.[15]Cinema Papers, Number 112 After praising Andrew de Groot’s cinematography and the ‘lack of condescension towards its Papuan characters’, Nery argues that the plot was its weak point which he reduced to ‘Kurtz meets Vertigo and Rebecca by the Sepik River’. This represents not only a crude distortion of the film but displays a failure to understand how the film’s ‘lack of condescension towards the Papuans’ is an integral part of the narrative (see above).

Nery criticises the film, as does Barbara Creed in her newspaper review, for its lack of psychological complexity and motivation with regard to the characterizations, particularly Jack’s obsession with his dead wife. Similarly Nery finds it difficult to understand why Kate should find such a morose character as Jack so attractive – Nery describes this as perverse. Exactly. It is perverse as perversity is integral to Gothic drama. The dramatic power of theatrical melodrama and film melodrama lies not with complex characterizations and psychological insights but with the excessive presentation of an intense bipolar conflict, as Peter Brooks points out:

There is no ‘psychology’ in melodrama in this sense; the characters have no interior depth, there is no psychological conflict. It is delusive to seek an interior conflict, the ‘psychology of melodrama’, because melodrama exteriorizes conflict and psychic structure, producing instead what we might call the ‘melodrama of psychology’. What we have is a drama of pure psychic signs … that interest us through their clash, by the dramatic space created through their interplay, providing the means for their resolution.

Consequently it is depressing when Nery cites Tie Me Up! Tie Me Down! (1990) as ‘more subversive and wiser about romance’ than Hillcoat’s film. This ‘apples/oranges’ comparison is hardly appropriate – what dramatic conventions does Pedro Almodovar’s Spanish comedy share with John Hillcoat’s Gothic drama? Vertigo, Rebecca or even Letter To An Unknown Woman (1948) would be more appropriate films for comparison for at least they belong to the same dramatic mode.

Nery’s review, and the other responses, would not really matter in the long run except they form part of a long-running pattern of Australian critical indifference to strongly profiled films that draw upon recognizable (Hollywood) generic structures and dramatic modes, such as melodrama and the Gothic. One of the most underrated Australian films of the 1980s, Goodbye Paradise (1983), which transplanted Raymond Chandler’s hard-boiled sensibilities to corrupt Queensland[16]See my comments on Goodbye Paradise in Brian McFarlane and Geoff Mayer’s New Australian Cinema: Sources and Parallels in American and British Film, Cambridge University Press, 1992, pp. 69-75., never enjoyed the credit it deserved, nor did Ray Barrett’s brilliant performance as the Philip Marlowe-inspired protagonist. Similar indifference greeted other melodramatic/generic Australian films such as Patrick (1978), Money Movers (1979), Roadgames (1981)[17]See New Australian Cinema, pp. 99-100., The Empty Beach (1985)[18]See New Australian Cinema, pp. 75-78., Grievous Bodily Harm (1988)[19]See New Australian Cinema, pp. 100-104. and Shame (1988)[20]Shame was not heavily promoted at the time of its first release – its virtues were only subsequently recognized by Geoff Mayer and Brian McFarlane (New Australian Cinema, pp. 87-90), Stephen Crofts and others..

The existence of self-appointed guardians to protect the Australian cinema from ‘foreign’, especially American, contamination is not new. Stuart Cunningham, in his study of Charles Chauvel, notes the opposition within the critical establishment in Australia in the 1920s to ‘imported models such as the society melodrama’.[21]Stuart Cunningham in his study of Charles Chauvel, Featuring Australia: The Cinema of Charles Chauvel (Allen and Unwin, 1991), distinguishes between ‘generic melodrama’ and ‘high melodrama’ – the latter is distinguished from the former by its ‘tonal consistency’ that often creates ‘generic inconsistency’. High melodrama, which Cunningham argues describes most of Chauvel’s work, ‘risks all, taking great liberties with aesthetic form and audience expectations’ (pp. 24-25). Similarly in 1981 Australian director Richard Franklin was sufficiently angered to write a letter to Uri Windt, of the Actors Equity Association of Australia, in defence of his films Patrick and Roadgames. This followed Windt’s assertion that these films somehow violated the purity of the Australian film industry through transplanted generic (read American) storylines and casting. Mad Max (1979) suffered the same kind of critical reaction from Phillip Adams. Unfortunately Adams, Windt and others did not object to the slavish copying of ‘imported’ European art cinema techniques, and recycled French New Wave devices, in the Australian cinema after the release of Peter Weir’s Picnic at Hanging Rock (1975) – a cycle that reached ludicrous proportions with Ken Hannam’s Break of Day in 1976 and continues to the present day.

This critical blind spot was also noted by Martha Ansara when she described the obstacles and frustrations faced by pioneering Australian producer/director Lee Robinson in the 1950s as he attempted to revive commercial filmmaking in Australia. Ansara argued that despite the increase in political support for Australian films since that time, the ‘film culture elite, in their nationalistic arrogance, still piss from a great height on the genre films which are today’s equivalent of the Lee Robinson action drama’.[22]Martha Ansara, “Lee Robinson”, Cinema Papers, December 1996, p. 17.

To Have and To Hold is both similar to and different from such generic films as Grievous Bodily Harm and Shame. It differs in that it is a stylized film that, in terms of its marketing strategies, targeted the ‘art-house’ clientele. Its similarities are based on the fact that it belongs to a narrative tradition, the Gothic, that in the 1930s and 1940s was an integral part of the popular Hollywood and British cinemas. From that tradition, Hillcoat’s film shares a belief in the reality of a world beyond representation and the existence of Manichæan moral structures. Its melodramatic rhetoric necessitates figures of hyperbole, antithesis and oxymoron[23]Peter Brooks, The Melodramatic Imagination, p.40. as it strives to break down everything that constitutes the ‘reality principle’, a principle that seems so prevalent in the Australian cinema.[24]I wish to acknowledge the assistance of Melissa Lehmann from Palace Films for assistance in facilitating this paper.

Endnotes

| 1 | Peter Brooks, The Melodramatic Imagination. Balzac, Henry James, Melodrama, and the Mode of Excess, Yale University Press, 1976, p. 19. |

|---|---|

| 2 | Peter Brooks, p. ix. |

| 3 | See Karl Quinn, “Drag, Dags and the Suburban Surreal”, Metro, Summer 1994/95. |

| 4 | Adrian Martin, “More Than Muriel”, Sight and Sound, June 1995, p. 32. |

| 5 | Peter Brooks, “Virtue and Terror: The Monk”, English Literary History, Summer 1973, p. 255. |

| 6 | Peter Brooks, The Melodramatic Imagination, p. 17. |

| 7 | Peter Brooks, “Virtue and Terror”, p. 255. |

| 8 | Peter Brooks, p. 255. |

| 9 | Peter Brooks, p. 249. |

| 10 | Peter Brooks, The Melodramatic Imagination, p. 18. |

| 11 | Peter Brooks, “Virtue and Terror”, p. 253. |

| 12 | Peter Brooks, p. 262. |

| 13 | Peter Brooks, The Melodramatic Imagination, p. 34. |

| 14 | See, for example, Suspicion, Rebecca, Gaslight (both American and British versions – 1944 and 1940), Jane Eyre (1944), I Walked With A Zombie (1943), Dragonwyck (1946) and Secret Beyond the Door (1948). |

| 15 | Cinema Papers, Number 112 |

| 16 | See my comments on Goodbye Paradise in Brian McFarlane and Geoff Mayer’s New Australian Cinema: Sources and Parallels in American and British Film, Cambridge University Press, 1992, pp. 69-75. |

| 17 | See New Australian Cinema, pp. 99-100. |

| 18 | See New Australian Cinema, pp. 75-78. |

| 19 | See New Australian Cinema, pp. 100-104. |

| 20 | Shame was not heavily promoted at the time of its first release – its virtues were only subsequently recognized by Geoff Mayer and Brian McFarlane (New Australian Cinema, pp. 87-90), Stephen Crofts and others. |

| 21 | Stuart Cunningham in his study of Charles Chauvel, Featuring Australia: The Cinema of Charles Chauvel (Allen and Unwin, 1991), distinguishes between ‘generic melodrama’ and ‘high melodrama’ – the latter is distinguished from the former by its ‘tonal consistency’ that often creates ‘generic inconsistency’. High melodrama, which Cunningham argues describes most of Chauvel’s work, ‘risks all, taking great liberties with aesthetic form and audience expectations’ (pp. 24-25). |

| 22 | Martha Ansara, “Lee Robinson”, Cinema Papers, December 1996, p. 17. |

| 23 | Peter Brooks, The Melodramatic Imagination, p.40. |

| 24 | I wish to acknowledge the assistance of Melissa Lehmann from Palace Films for assistance in facilitating this paper. |