In its first week of release, Ivan Sen’s Goldstone (2016) made A$420,000 at the box office.[1]Box Office: Thursday July 14, 2016’, Urban Cinefile, <http://urbancinefile.com.au/home/boxoffice.asp>, accessed 17 August 2016. That is nearly as much as what its predecessor, Mystery Road (Sen, 2013), amassed in its entire theatrical run.[2]Mystery Road made A$379,413 at the 2013 box office; see Don Groves, ‘2013 Another Down Year for Aussie Films’, IF.com.au, 3 December 2013, <http://if.com.au/2013/12/03/article/2013-another-down-year-for-Aussie-films/HNYVTGBVTC.html>, accessed 17 August 2016.

Few Australian-made film sequels exist – Wolf Creek 2 (Greg McLean, 2013), Wog Boy 2: The Kings of Mykonos (Peter Andrikidis, 2010) and Red Dog: True Blue (Kriv Stenders, 2016) are rare examples – and even fewer that have involved such a quick turnaround (George Miller’s 1981 Mad Max 2: The Road Warrior and John Cornell’s 1988 Crocodile Dundee II are the exceptions). That it took only two years to produce a follow-up for a film that was not a box-office hit but was critically successful is a testament to Sen’s skills as writer/director and to the audience’s and funding bodies’ appetite to see more of Indigenous detective Jay Swan (masterfully performed by Aaron Pedersen).

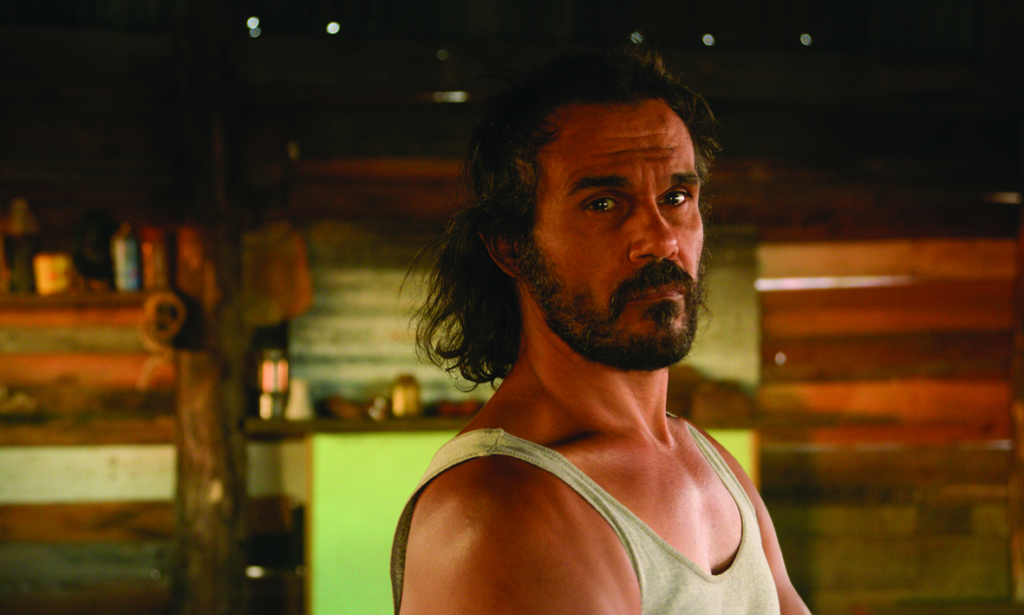

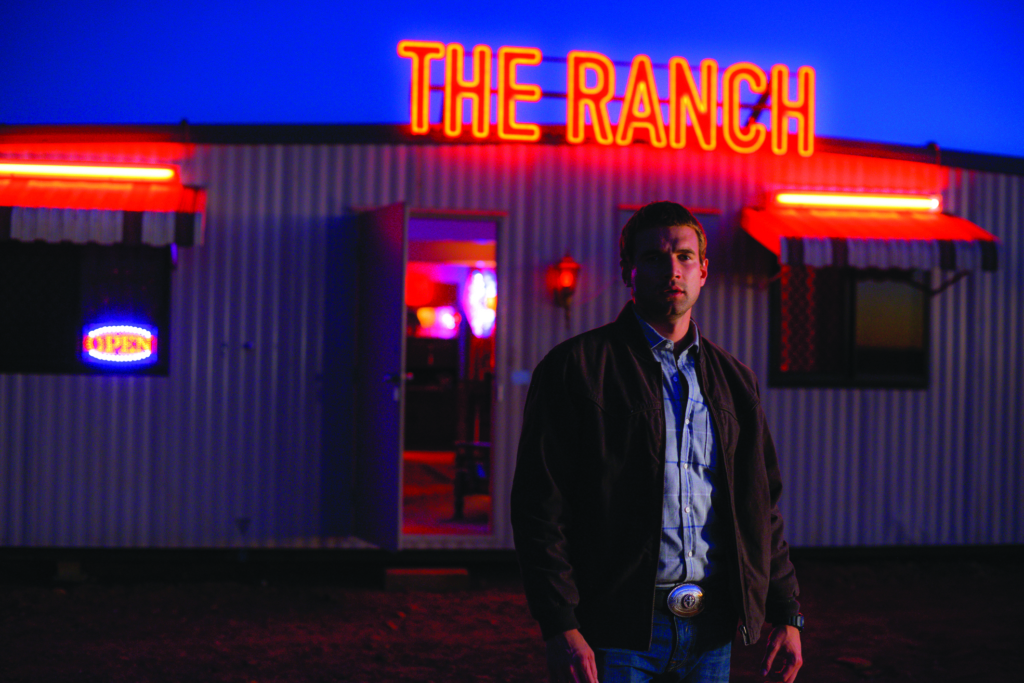

In Mystery Road, Jay came into town as the cowboy-superhero ready to clean up the crime and corruption that were targeting young Indigenous women. In Goldstone, set a few years later, he rolls into the titular town plastered. The swagger is gone, he drinks to forget, and he has gone through all manner of suffering since his last triumph. He is on a mission to find a Chinese girl whose disappearance is somehow linked to the dubious mining operations at Furnace Creek, which provides many of the townsfolk’s employment. Jay is partnered with young cop Josh (Alex Russell), who makes it clear that the detective’s enquiries are not welcome. Once again, Jay encounters a smiling wall of resistance from white powerbrokers – in particular, mining mogul Johnny (David Wenham), who seeks to expand the industry and has nefarious designs on Indigenous lands. This time, however, the opposition Jay faces is compounded by the involvement of Indigenous figures. Importantly, Aboriginal Land Council boss Tommy (Tom E Lewis) is on the take from the mine and shares an interest in quashing Jay’s investigation.

The mainstream arthouse

Sen’s achievement with both Goldstone and Mystery Road lies in the way he confronts serious issues while tapping into the entertainment values enabled by genre filmmaking, recognisable Australian stars and stunning outback locations. The drama is fuelled by the protagonist’s investigations regarding the harrowing exploitation of marginalised characters, and the ensuing action becomes an exploration into the fractures at the heart of Indigenous–white relations. All of this is a seductive ploy to attract a broader audience than Sen’s earlier arthouse films could ever have hoped to achieve. Sen, in fact, noted in 2013 that Mystery Road was aimed primarily at arthouse audiences while also ‘pushing hard at the fringes of the multiplexes’.[3]Ivan Sen, quoted in Jason Di Rosso, ‘Landing the Dream: Ivan Sen’, Lumina, issue 11, 2013, <https://www.aftrs.edu.au/media/books/lumina/lumina11r-ch5-2/index.html>, accessed 17 August 2016. While that film was ultimately not a commercial success, it consolidated the production recipe – which integrates genre, high-profile actors, focused artistic control and a tough Indigenous thematic – that the director has built throughout his past projects. Arthouse audiences will not soon forget the pared-back impact of Beneath Clouds (2002), the handmade authenticity of Toomelah (2011) or the simmering documentary work in A Sister’s Love (2007).

The film’s message may be more explicit, but so is the dramatic action. The narrative’s pace is accelerated; Goldstone has more guns, more bad guys, more scantily clad women, and a broader dispersal of evil than Mystery Road.

Compared to those of his earlier work, Goldstone’s political themes are certainly more clearly foregrounded – and Sen admits he was conscious to entice the right mix of viewers:

Some people are just there for the gun battle. Which is fine. But then, hopefully, they take on board that cultural perception that underpins the fabric of the action. Then you’ve got people who are interested in Indigenous films, but who might not normally go to genre movies. The trick is, then, balancing that so you don’t [alienate] either audience.[4]Ivan Sen, quoted in Anthony Carew, ‘Creating Films with Real-life Meaning in a Town with “Literally Nothing”’, TheMusic.com.au, 6 June 2016, <http://themusic.com.au/interviews/all/2016/06/06/ivan-sen-goldstone-anthony-carew/>, accessed 17 August 2016.

The film’s message may be more explicit, but so is the dramatic action. The narrative’s pace is accelerated; Goldstone has more guns, more bad guys, more scantily clad women, and a broader dispersal of evil than Mystery Road.There is a terrifically inventive final shoot-out, with a sprinkling of dark humour, that captures the complex ingredients demanded by the genre. At this level, Goldstone proves to be an unexpected action-filled buddy film like Lethal Weapon (Richard Donner, 1987), featuring a mismatched pair of detectives going head-to-head against corrupt head honchos and overturning initial audience expectations of black drunkenness and white dissipation.

A genre called ‘outback noir’?

Much of the discussion around Goldstone has revolved around genre. Luke Buckmaster, for instance, claims that Sen combines two cinematic forms that Australian cinema has never truly tackled, the western and film noir,[5]Luke Buckmaster, ‘Goldstone Review – a Masterpiece of Outback Noir That Packs a Political Punch’, The Guardian, 9 June 2016, <https://www.theguardian.com/film/2016/jun/09/goldstone-review-a-masterpiece-of-outback-noir-that-packs-a-political-punch>, accessed 17 August 2016. while John McDonald contends that Sen explores a relatively new subgenre: ‘Let’s call it Outback Noir. Instead of darkened rooms and night clubs, the action takes place in the blazing Australian desert.’[6]John McDonald, ‘Goldstone Takes Film Noir into Outback Noir’, Financial Review, 6 July 2016, <http://www.afr.com/lifestyle/arts-and-entertainment/film-and-tv/goldstone-takes-film-noir-into-outback-noir-20160706-gpzhs6>, accessed 17 August 2016. The notion of ‘outback noir’ is particularly appealing for its incongruity: it inverts the traditional noir iconography of the nocturnal urban setting, and transposes it onto a landscape scorched by sun. Eddie Cockrell even sees clear comparisons between Goldstone’s predecessorand Roman Polanski’s 1974 period drama, Chinatown:

Both are sun-drenched films noirs, both feature commanding protagonists who spend much of the film doing wrong things for the right reasons, and both feature climactic showdowns in places laden with metaphor.[7]Eddie Cockrell, ‘Sun-drenched Film Noir’, The Australian, 17 August 2013, <http://www.theaustralian.com.au/arts/review/sun-drenched-film-noir/story-fn9n8gph-1226698413712>, accessed 17 August 2016.

While Australia has a long tradition of producing crime films, the majority are not considered to be films noir largely due to matters of style, visual iconography and the absence of archetypal features. Yet this is not to say that noir has not been represented in Australian cinema. In 2009, Richard Sowada programmed a retrospective of Australian noir films for the Australian Centre for the Moving Image, featuring, among some surprising examples, Ted Kotcheff’s 1971 classic, Wake in Fright. In an interview with Greg King, Sowada explains the selection:

We chose that one not so much because of the noir characterisations, but because of the noir use of setting as a character […] it’s so claustrophobic that you feel like there’s never any air. I think that that’s one of the noir traits, that the environment that the characters inhabit is actually a player in itself, and forces them to do certain things that they wouldn’t necessarily do.[8]Richard Sowada, quoted in Greg King, ‘Australian Noir Retrospective – Interview with Richard Sowada, ACMI’s Head of Programming’, Greg King’s Film Reviews, <http://filmreviews.net.au/australian-noir-retrospective-interview-with-richard-sowada-acmis-head-of-programming/>, accessed 17 August 2016.

If a productive argument can be made for classifying Wake in Fright as an outback noir, then Goldstone sits comfortably alongside it. Despite the film’s vast landscapes, Goldstone’s drama happens in enclosed spaces that are steamily claustrophobic, and the mining locations are undeniably the ‘agents’ of corruption in the community.

In the Australian context, noir examines ancestral trauma – that of both Indigenous and settler. Outback noir challenges official versions of events that glide over historical massacres and current injustices.

Film noir protagonists are seldom creatures of light. However, in the Australian outback – with its blinding sun and parched landscape – the light conceals far more than it reveals. Indeed, it is in the bright midday sun that Goldstone’s threats are unveiled, among ostensibly innocuous offerings such as tea and freshly made cake. It is in the heat of the day that bribes are offered; murders, executed; and honest cops, attacked. And, conversely, it is in the dim glow of neon-lit brothels, in seedy bars and in dark, ramshackle cabins that the pursuit of truth and justice is initiated. Making a case for an Australian-set noir, Allan Cameron writes:

noir’s characters, plots and dark perspective can be reshaped and placed into distinctly Australian settings. Ultimately, what makes noir so compelling is its willingness to delve into the murky corners of human experience, revealing hidden fears and desires and unearthing hard moral questions.[9]Allan Cameron, ‘The Edge of the Known World: Mapping Australian Noir’, Lumina, issue 2, 2010, <https://www.aftrs.edu.au/media/books/lumina/lumina2-ch5-2/index.html>, accessed 17 August 2016.

Beyond the film’s use of landscape as archetypal character, it is surprising just how responsive Goldstone is to a noir assignation. Sen asks hard questions about cross-cultural collaboration, the use value of human beings, the right balance between commercialism and community, and methods for healing historical trauma. Jay is no longer a cowboy-superhero but rather a haunted detective who finds solace in drinking and smoking, and his primary role is to motivate young white cop Josh to commit to investigating the truth. What makes Jay and his unorthodox methods so compelling are his ‘handicaps’ – he is weakened by a sense of despair that all his good work has not made a lasting impact.

Haunting and healing

Traditionally, film noir explores the moral trauma of crime on its protagonists, who are often escaping personal suffering or harrowing incidents from their pasts. In the Australian context, noir examines ancestral trauma – that of both Indigenous and settler. Outback noir challenges official versions of events that glide over historical massacres and current injustices. This aspect of Goldstone is foreshadowed in its very opening: like the revisionist Australian western The Proposition (John Hillcoat, 2005), Sen’s film begins with a small deck of sepia photographs from the gold-rush era. In Goldstone, however, they are not just standard photos of white diggers, but rather images of Indigenous and Chinese figures on the goldfields – subtly commenting on the historical interconnection between Aboriginal and Chinese people in the context of mining and their exploitation within it. These ties are then thrust into the diegetic present: Jay is on assignment investigating a missing person – not an Aboriginal woman (as in Mystery Road), but a Chinese woman. Young Asian women are being flown in to the town to become sex workers serving Furnace Creek’s miners and, just like Australia’s Indigenous people, these women are deprived of their rights. They are mining infrastructure; no-one seems concerned about them.

Ancestral trauma is depicted on a personal level as well. Jay is dispossessed from the land of his ancestors, his community and his family. In what is perhaps the finest scene in the film, however, he undergoes a form of spiritual healing with the guidance of Aboriginal elder Jimmy (David Gulpilil) – we watch their dreamy, wordless passage on a bark canoe down the narrow Cobbold Gorge, past red boulders and rock art. This connection gives Jay strength and starts his healing journey. We also discover what drives mayor Maureen’s (Jacki Weaver) gutless action. After offering Jay homemade apple cake in her kitchen, barely concealing her threat that he should cease any further meddling, she reflects on the toughness of her grandfather and father. It is not clear what she means by ‘hard men’, but it can be assumed that they were uncompromising in their exploitation of the land and its original inhabitants. It is this intergenerational expectation of ‘hardness’ that she is both in thrall to and struggling to meet.

In an earlier scene, Josh – after Jay’s coaxing – is impelled to investigate and speaks to May (Michelle Lim Davidson), a Chinese woman imprisoned in the local brothel. Provocatively, she asks him, ‘What are you looking for?’, to which he replies, ‘The truth.’ She then gives him that languorous femme-fatale look and asks, ‘And what are you going to do with the truth?’ It is a difficult moral choice for a single man stationed in a hellhole, sitting opposite a beautiful woman, to go against the town’s powerbrokers instead of just returning to a life of fulfilling ‘light duties’. Yet, like Jay, he must overcome his demons and make himself fit to protect the vulnerable.

Facing the past

The past of a noir protagonist is no fleeting phantom. It is tangible, powerful and menacing. In the noir world, past and present are inextricably bound; in Goldstone’s case, all the characters – from Jay to Maureen – cannot escape where they have come from, no matter how hard they try. And it is only in confronting their ancestral traumas that they can hope for some kind of redemption. Goldstone is preoccupied with characters both burdened by their pasts and lost in a landscape that is at once epic and scarred by exploitation and injustice. And, through its criminal investigation, which embodies a kind of communal ceremony, it exposes corruption and offers a form of healing for these sun-scorched people.

A feature of Sen’s cinematography is his sparse but effective use of bird’s-eye-view shots. While this technique was employed in Mystery Road, its continued presence in Goldstone provides the audience with a startling image that requires interpretation. It could be read as a mere topographical map, or as an approximation of an Aboriginal dot painting. In some ways, it is reminiscent of The Third Man’s (Carol Reed, 1949) Harry (Orson Welles) comparing the people he sees from atop a Ferris wheel to insects; if one of those specks disappeared forever, he ponders, would anyone really care? May’s question about truth did not get an answer. Jay and Josh’s investigation is not complete. But, in Sen’s vital examination of crime and trauma in outback Australia, each of those busy insects has a life worth caring about.

http://www.goldstonethemovie.com

Endnotes

| 1 | Box Office: Thursday July 14, 2016’, Urban Cinefile, <http://urbancinefile.com.au/home/boxoffice.asp>, accessed 17 August 2016. |

|---|---|

| 2 | Mystery Road made A$379,413 at the 2013 box office; see Don Groves, ‘2013 Another Down Year for Aussie Films’, IF.com.au, 3 December 2013, <http://if.com.au/2013/12/03/article/2013-another-down-year-for-Aussie-films/HNYVTGBVTC.html>, accessed 17 August 2016. |

| 3 | Ivan Sen, quoted in Jason Di Rosso, ‘Landing the Dream: Ivan Sen’, Lumina, issue 11, 2013, <https://www.aftrs.edu.au/media/books/lumina/lumina11r-ch5-2/index.html>, accessed 17 August 2016. |

| 4 | Ivan Sen, quoted in Anthony Carew, ‘Creating Films with Real-life Meaning in a Town with “Literally Nothing”’, TheMusic.com.au, 6 June 2016, <http://themusic.com.au/interviews/all/2016/06/06/ivan-sen-goldstone-anthony-carew/>, accessed 17 August 2016. |

| 5 | Luke Buckmaster, ‘Goldstone Review – a Masterpiece of Outback Noir That Packs a Political Punch’, The Guardian, 9 June 2016, <https://www.theguardian.com/film/2016/jun/09/goldstone-review-a-masterpiece-of-outback-noir-that-packs-a-political-punch>, accessed 17 August 2016. |

| 6 | John McDonald, ‘Goldstone Takes Film Noir into Outback Noir’, Financial Review, 6 July 2016, <http://www.afr.com/lifestyle/arts-and-entertainment/film-and-tv/goldstone-takes-film-noir-into-outback-noir-20160706-gpzhs6>, accessed 17 August 2016. |

| 7 | Eddie Cockrell, ‘Sun-drenched Film Noir’, The Australian, 17 August 2013, <http://www.theaustralian.com.au/arts/review/sun-drenched-film-noir/story-fn9n8gph-1226698413712>, accessed 17 August 2016. |

| 8 | Richard Sowada, quoted in Greg King, ‘Australian Noir Retrospective – Interview with Richard Sowada, ACMI’s Head of Programming’, Greg King’s Film Reviews, <http://filmreviews.net.au/australian-noir-retrospective-interview-with-richard-sowada-acmis-head-of-programming/>, accessed 17 August 2016. |

| 9 | Allan Cameron, ‘The Edge of the Known World: Mapping Australian Noir’, Lumina, issue 2, 2010, <https://www.aftrs.edu.au/media/books/lumina/lumina2-ch5-2/index.html>, accessed 17 August 2016. |