bedevil: 1. “to treat diabolically; torment maliciously”

2. “to possess, as with a devil; bewitch”

3. “to confound; muddle; spoil”[1]All definitions are from the Macquarie Dictionary.

beDevil is intensely Australian in ways both familiar and strange. The characters inhabit real and imagined north Queensland landscapes – mostly bizarre, hyperbolic, and artificial (created in a warehouse studio by production designer, Stephen Curtis, an army of carpenters and other set technicians) representing the heightened locations of memory, with some actual, realistic locations from the televised present. Another of the film’s landscapes is, as Moffatt has said, the landscape of the face. The film is always beautifully composed in frames reverberating with the thrilling and threatening music of Carl Vine layered with noise, natural sounds, voices and silence in disturbing and unsettling ways.

In fact, a lot about beDevil is unsettling; and meant to be. Its layers of hyperbole and the everyday, documentary and dreamlikeness, tragedy and slapstick bleed into each other in a way much more psychically true than the realist dramas and brightly coloured comedies that typify Australian feature film. “I’m not concerned with capturing reality, I’m concerned with creating it myself”, Moffatt has said (in a 1988 interview with Anna Rutherford).[2]Rutherford, Anna, “Changingthelmages”, Aboriginal Culture Today, Dangaroo Press – Kunapipi, vol x, nos 1 and 2, 1988

This is also personal work for Moffatt who makes sure she never presents herself as a stationary target, and whose public presentation of herself is as carefully crafted as her art works, and covers the same kind of ground.

She has several times publicly demanded to know why people sometimes have so much trouble accommodating the Aboriginal and avant-garde in her work. (And, after all her films and photographic series repeatedly demonstrate why – in Australia now – “avant-garde” and “Aboriginal” are in some ways inescapably interlinked.)

She has acknowledged that many people, Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal, think experimenting with film form, while there are so many potentially and actually fatal pressing social and political problems, is to fiddle while Rome burns. She knows things need to be said, but aims to do it in more interesting ways. Which she does.

As she points out, her film work is experimental partly because it challenges conventional ways of representing Aborigines in film. Actor, Kylie Belling, in an article in the Green Guide (Melbourne Age, November, 1993), pointed to some of these narrow openings: “When I was doing Flying Doctors years ago, I would say that I was adding background flavour … seeing a Koori face added a certain texture to it – I was really adding to the contact it was set in”; and “I always say the Koori episode is fitted in between the wheelchair episode and the lost dog episode.” Aboriginal people as ill victims.

On another hand, asked to describe herself by Ruth Hessey (Juice, October 1993), Moffatt, whose well-developed taste for tacky B-grade iconography and language was most recently exemplified in her video clip for Australian international mega band, INXS, replied “brown trash”. Excuse me? Brown trash? “I’m celebrating that fact that I come from nothing, but I can re-invent myself enough to convince people to hand me $2.5 million to play with film.”

These reinventions on two fronts are related. beDevil recognises the blurred boundaries between things often represented as being essentially opposed, mutually exclusive or incomprehensible – the natural and supernatural, natural and artificial, culture and impulse, inner and outer worlds, the visible and invisible, past and present, indigenous and foreign.

Moffatt works at “the intersection between the historical and the psychic”, as Anne Kaplan put it.[3](Quoted in) Langton, Marcia, Well, I heard it on the radio, and I saw it on the television, Australian Film Commission, Sydney, 1993.

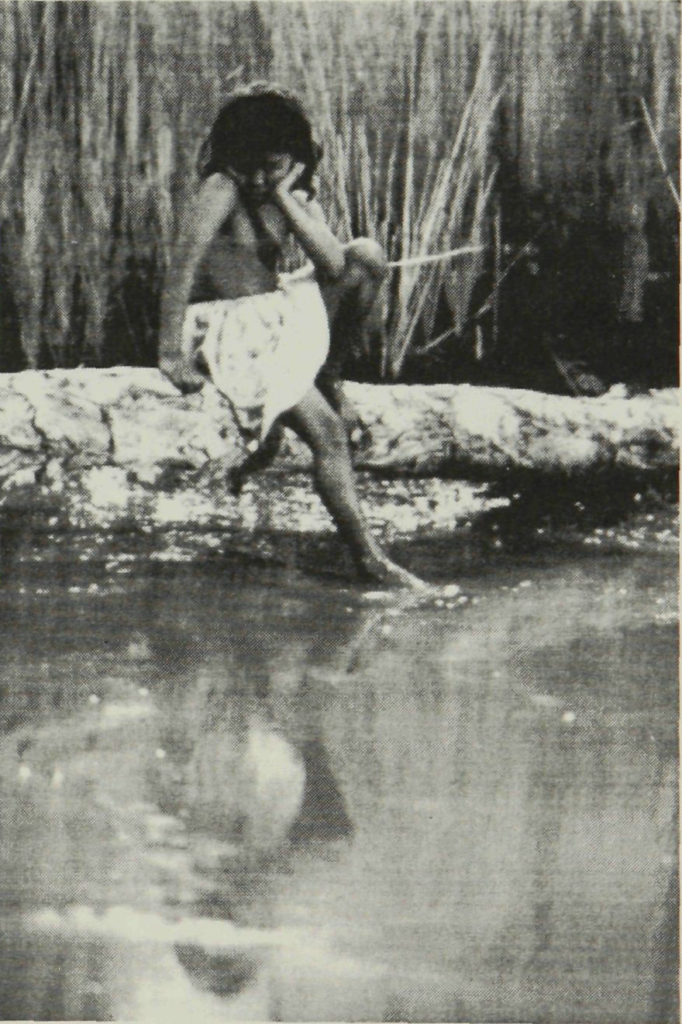

As a set of spooky stories, beDevil goes like this. In Mr Chuck, an American Gl stationed on a North Queensland island during world war two drove his tank into the quicksand swamp after a party, and afterwards haunted the spot and the cinema built over it. This tale is told in the creature from the primeval slime tradition with touches of muscular ectoplasmic possession. Mr Chuck is a grabbing, grappling thing, physical, malevolent and personal whose target is the child Rick. (And this is neither the beginning nor end of Rick’s troubles. For instance, there is a pale, reptilian father, the architect or owner of the cinema in question, who fondles and pets his son in the bright artificial daylight on the site of the partly constructed building; Rick watches; cut to father’s head in profile, a silhouette with its pointed tongue out, licking. Another man, seen only as a shadow with voice like a dog barking, does something violent to Rick behind closed domestic doors. The ghost first assaults Rick by dragging him by the ankles into a violent embrace in the murky waters of the swamp, and later by forcibly licking his feet captured through a hole in the picture theatre floor. (Artist Fiona Foley, the designer of the black cockatoo stamp in the Aboriginal art series, called her recent exhibition Lick My Black Art. What is this about licking? Take a licking, lick my boots, lick my …?)

In Choo Choo Choo Choo practically everyone is haunted by something. While the children see magical mysterious lights in the sky, the adults variously experience a plague of little wooden white faced poppets accompanied by inexplicable weather and a wind full of chopped up white bird feathers, an invisible but audible mechanical apparition in the form of a disembodied train, as well as several ghostly manifestations in female human form. This story draws on the ordinary or harmless thing turned sinister by context, the thing only partly glimpsed or heard, the bewitching and enchanting thing that paralyses the seer or hearer, turning them temporarily into zombies.

Lovin’ the Spin I’m In is the classic fully visible and audible haunting apparent to anybody and everybody on the spot. A pair of lovers who died in unexplained but violent circumstances vigorously haunt a warehouse in a north Queensland coastal town, dancing and fighting after death as they did in life. There is love magic made with spells, taboos broken and paid for, and variously grief, voyeuristic thrills, and eyepopping frights for those in their orbit.

It would misrepresent the film to say that these stories are entirely or even primarily the point. In one interview (with Shane McNeil in Lip Sync, August-September 1991) Moffatt quoted English filmmaker, Nicolas Roeg: ‘ I like to work around the human condition. The plot is just a shell to me … I’m more interested in the inhabitants of that plot … I’m not driving at anything. I’m merely observing. That’s what generates the drama for me.’

“beDevil is like this, “Moffatt has said, “we see these characters, we are going to hang out with them for a while …” (Cinema Papers, John Conomos and Raffaele Caputo, May 1993).

Memories are intercut with commentaries from the present by participants in and witnesses to the past, counterpointed by the same witnesses in other, at first often apparently unrelated scenes from the present, as well as literal and metaphoric interpolations – sky, a piece of braille, people in a street making train movements with their arms, touching their ears and covering their eyes to mimic blindness (a visual restatement of the refrain “you can hear it, but you can’t see it” from Choo Choo Choo Choo).

There is almost no direct reference besides what is visible from physical appearance, clothing, movement in places and scraps of dialogue, to the varied race, sex, age or other socially and politically locating qualities of the characters, though the friction and dissonance generated by power relations around these things is a very strong undertone. This is a deeply refreshing approach in Australian film where Aboriginal characters are rarely written to represent ideas about the human condition generally, and rape is still apparently confused with courtship.

The drama, personal and general develops in the characters’ face, their bearing in weird, often poisonously coloured environments, ambiguous atmospheres, and startling shifts between present and past (and between different pasts). The film is chock-a-block with allusions to other films and filmmakers as well as gestures composed of generic and classic filmic moves-weather, background colour, silent film type tinting of the scene, staccato music, growling music, rafts of strings all used to foreshadow or underline emotions and events, as well as phrases from particular other work that thicken, counterpoint, or jest. Moffatt has mentioned the Japanese filmmaker Masaki Koyabashi, Australian Peter Weir (especially the film Walkabout), and English director, Nicolas Roeg. Other people’s articles have frequently mentioned Hitchcock, TV situation comedies, travelogues, and numerous others.

I would like to add the Chauvels’ 1955 melodrama, Jedda, to the top of the list.

At the Queensland College of the Arts where Moffatt studied, “Our teachers didn’t push our appreciation of film theory at all, but what we did was watch a lot of films. Everything from early Australian silent films to Italian neo-realist films of the 50s – the French new Wave – a hotch-potch. Basically I learnt to make films just through watching them” (Lip Sync).

A lot of film has gone into Moffatt, and a lot has come out. Among other things, beDevil is a sophisticated play with film language and form both visual and aural, as well as an essay on memory and the way the past pulls strings in the present; all boldly presented as popular entertainment.

Early publicity for beDevil playfully called it “scary, funny and arty”. Asked in 1991 about the boundaries between experimental and political film in her work, Moffatt replied: ” I say it’s just a film, it comes in a can so it must be a film, why neatly label everything? I think it’s very important to have a ‘What the hell’ attitude. You have to, it’s about entertainment really, you’ve got to engage an audience. Whatever sort of film it is, whatever it’s about, it’s showbiz. You shouldn’t pretend it’s anything else” (Lip Sync).

Shortly before its cinema release (by which time the promotional hook had become “when the unexplained happens”), Moffatt said: “I certainly hope beDevil can appeal to a wide-ranging audience and that people will appreciate my play with form. Non-linear cinema has been around for a long time and, because we are a very visual culture, I think audiences are now quite open to it” (Cinema Papers).

This assessment soon proved to be an over-estimation of cinema going audiences and the gatekeepers of that particular consumer culture. Appreciation of the film’s many visual and aural pleasures in mass media reviews has been generally tempered by bewilderment and impatience at its unconventionally unfolded narratives. On a first viewing only “arty” and “unexplained” have been obvious to many, and more than one critic’s interest has completely terminated in curmudgeonly irritation and confusion over what it’s about.

beDevil’s immediate appeal is directly to the eye and ear – the first work of any film; it looks fabulous and sounds exciting; but it probably takes at least a second viewing to understand the stories, and as many more as you like to get the details. And it is thick with detail; like a complex perfume on the skin, it takes a while for it to develop a personal flavour.

Some confusion at a first viewing is probably inevitable. Both picture and sound cut between past and present (not always at exactly the same time), between narrative and commentary, and between the various faces of the participants in and witnesses to the several hauntings. Confusion is compounded by the physical dissimilarity of the actors playing characters at different ages. It’s highly coded, but it’s a puzzle which anybody who’s seen plenty of moving pictures has the equipment to crack.

code: “a systems of symbols for use in communication”, “a symbol (made up of signs, numbers, letters sounds, etc) in such a system” and “a set of words, pictures or other readily recognised symbols used for conveying messages briefly”.

It must be said, though, that how much a viewer immediately “gets” depends somewhat on how film I iterate they are and which films referred to they have seen and remembered, or how inspired they are to take up the many suggestions Moffatt incidentally makes. beDevil is the perfect central text for an education in Australian film and its influences as long as one has access to the many films it refers to (and this is more easily said than done, given the virtual unavailability of many of them).

It is a clever and intellectual work, rooted in film history and language, nearly perfect as an educational text with its combination of surface glamour, and inner detail, between which is a gap for investigation, which is where its complex meanings develop.

At first reading, the code intended can seem more like the one that’s “a system of arbitrarily chosen symbols, words, etc. used for secrecy”. Rather than coded beDevil can seem arcane: “mysterious; secret; obscure”. The example of use given by the dictionary for this inflection is: “poor writing can make even the most familiar things arcane”. For some reviewers this summed it up.

In fact, there is little that is arbitrary or accidental about this film. It took two years to write, and went through six drafts, was a year being story-boarded, and Moffatt took the opportunity to tune it at every stage of production.

The handful of industry professionals who make up each pre-selection panel for the AFI Awards, the Australian film industry’s equivalent of the US Academy Awards, in an act that does seem arbitrary, choked off its passage from entry to nomination in any category. beDevil‘s co-producer, Anthony Buckley, pours well-deserved scorn on this failure of nerve or judgment, and critics Margaret Pomeranz and David Stratton (who has given it the warmest of reviews at every opportunity) described the omission as outrageous; which it is; and ironic too considering that the plot of last year’s AFI Awards star, Strictly Ballroom, pivoted on conflict between innovation and jealously guarded regulation of a form (in that case, of competition dancing).

Just before its first Melbourne cinema release (now over) Moffatt was quoted as saying more defensively: “When you make something like this, it’s bound to evoke extreme reactions. People go for it or they don’t. I didn’t set out to make a popularist film.” Pat Gillespie (On Screen – Melbourne Times, 27 October, 1993).

Elsewhere, however, beDevil was nominated for the Uncertain Regard section of the 1992 Cannes Film Festival, was an official selection at the Toronto, London and Hawaiian film festivals and was invited to many others (too many in fact to accept all of the invitations co-producer, Anthony Buckley said). It won this year’s award for best sound at the Festival of Fantastic Cinema in Barcelona.

beDevil‘s combination of virtuoso pun, pastiche, collage, and bricole has also appealed strongly to other Australian audiences, writers in specialist film and art publications, academic writers, and the fashionable, the modern and the post-modern.

virtuoso: “one who has special knowledge or skill in any field … a connoisseur of works”

pun: “the humorous use of a word in such a manner as to bring out different meanings or applications, or of words alike or nearly alike in sound but different in meaning”

pastiche: “any work of art, literature or music consisting of motifs borrowed from one or more masters or works of art”

collage: “a pictorial composition made from any of a combination of various materials … affixed in juxtaposition … and often combined with colour and line from the artist’s own hand”

bricole: a term used to describe oblique shots in billiards and royal tennis, in which the ball is bounced off the cushion or side wall to hit its mark, and more generally any “indirect action OT unexpected stroke”

A related word bricolage – “the use only of the materials or tools at hand to achieve a purpose” – is also relevant, not for the suggestion is has of the famous mend with fencing wire, but because it brings up the question of what tools any filmmaker might have at their disposal.

Its meaning is not so much the elements of the stories but the paths they trace as they bounce and ricochet about picking up nuance.

In the interview with Ruth Hessey, Moffatt said: “The stories are not about evil. They’re more about memory and the ghosts of the past, and why some people don’t rest.”

Hessey: “That’s a quality of the whole Australian psyche. Our whole attitude to history, this sense of the past not having been laid to rest. You turn around and you still can’t see it properly.”

Moffatt: “That’s good. Shit, I wish I’d thought of that.”

Hessey: “You did, you made the film about it.”

beDevil sustains many viewings. With acquaintance, its small awkwardnesses recede in importance, and its many thoroughly considered intellectual dimensions and sensory pleasures expand. As Moffatt told Paul Calder of the New Zealand Herald (July 23, 1993) on a promotional tour for the film: “In other words, it’s not designed to be consumed only in the theatre.”

Endnotes

| 1 | All definitions are from the Macquarie Dictionary. |

|---|---|

| 2 | Rutherford, Anna, “Changingthelmages”, Aboriginal Culture Today, Dangaroo Press – Kunapipi, vol x, nos 1 and 2, 1988 |

| 3 | (Quoted in) Langton, Marcia, Well, I heard it on the radio, and I saw it on the television, Australian Film Commission, Sydney, 1993. |