According to director Ivan Sen, ‘Mystery Road is a Western, a crime thriller, a murder mystery [and] a genre film, but from an Indigenous perspective’. It is a remarkably significant film that rewrites the traditional ‘black tracker’ narrative arc and introduces an Indigenous hero while employing an intimate production method. It was the first time in its sixty years that an Indigenous film has opened the Sydney Film Festival. Judging by the warm reception that the film received from the sold-out audience, Sen has hit the right balance between a mainstream genre film and a sophisticated, tense arthouse project.

Sen has a knack for subtly transforming established narrative tropes. In Toomelah (2011) he rewrote the ‘lost child’ trope that recurs in numerous Australian cultural texts[1]See Peter Pierce, The Country of Lost Children: An Australian Anxiety, Cambridge University Press, 1999. into an Indigenous-kid gangster film where bad boy Daniel (Daniel Connors) finds himself in an otherwise destitute landscape. At the 2008 Message Sticks Film Festival, Sen promised that he would make an Aboriginal sci-fi film. While that may have become his film Dreamland (2009), there is every chance that this science fiction idea – a world much like ours but different, a ‘what if’ narrative – underpins Mystery Road. The idea of a superhero Indigenous cop negotiating a complex path between his past and the white universe – handling the racism with a smile but achieving real results where others would have stormed away – does sound like the best science fiction: at once familiar and strange.

The original ideas for the film emerged from Sen’s family history, his ancestors and his earlier films. A few years ago, his mother’s distant cousin was found dead under the roadway in northern New South Wales. She had been stripped and brutally murdered. In 2007, Sen produced A Sister’s Love, a searing investigative documentary that unravelled the mysterious circumstances surrounding the disappearance of Rhoda Roberts’ sister in her Bundjalung homeland. She was brutally murdered but the police did not act on the available information and the perpetrator has not been brought to justice. Although conceived in 2006, the first draft of Mystery Road was based on research that Sen undertook around the time he was doing Toomelah. It was provisionally titled ‘Moree Girls’ and was based on conversations with and observation of teenage girls that he met in Moree. He shifted away from that approach when he realised that it was perhaps too similar to the observations of young boys in Toomelah. Nonetheless, teenage girls are at the dramatic core of Mystery Road, although now interwoven with the themes of the black tracker, trouble within an outback community and police inactivity on Indigenous deaths.

Teenage girls are at the dramatic core of Mystery Road, although now interwoven with the themes of the black tracker, trouble within an outback community and police inactivity on Indigenous deaths.

Between two worlds

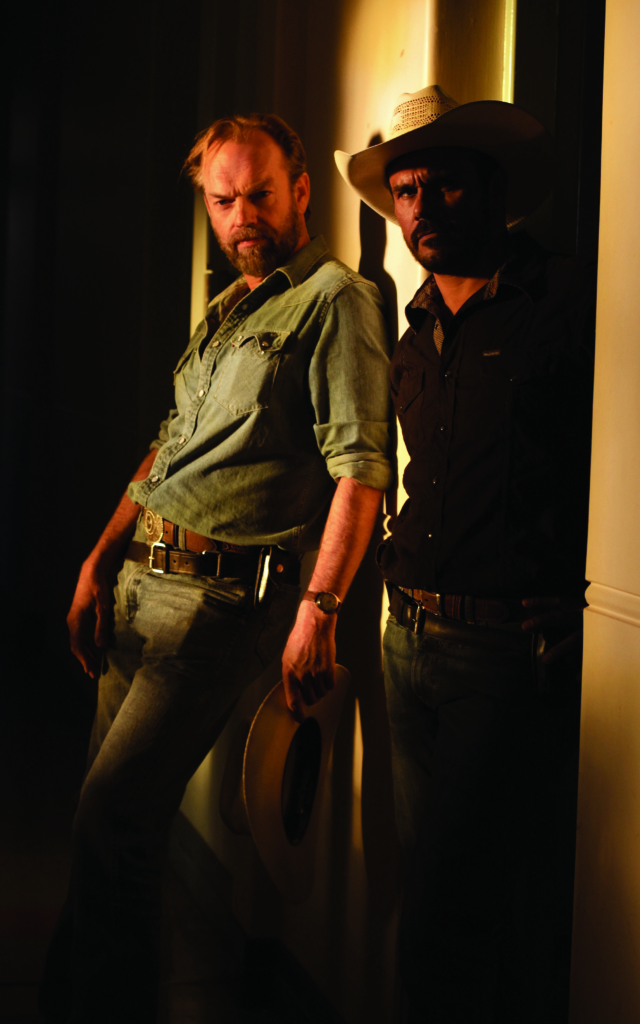

After a long stint in the city, Jay Swan (Aaron Pedersen) returns to his outback home town to take up his posting as a detective with the local police force. He comes straight into investigating the brutal and inexplicable murder of a teenage Aboriginal girl. Her body is discovered in a drainpipe under the highway at Massacre Creek. He knows the girl. It turns out that she is not the first girl to be murdered recently, but the old police sergeant (Tony Barry) does not think this is significant as it looks like she was prostituting herself to truck drivers. He cannot allocate any further resources. Jay becomes the lone ranger seeking the truth of her death. His search leads him into the labyrinth of lies, distrust and old hatreds as he delves deeper into the sordid underbelly of his troubled outback town. Paradoxically, the perpetually sunny, open-fronted, fenceless suburbia of the public housing estate in a middle-of-nowhere town conceals a network of darkness and sordid affairs that implicate the entire community. As Jay delves deeper into the mystery he is confronted with his own past and the complex relationship he has with his ex-wife. He discovers how his own teenage daughter, Crystal (Tricia Whitton), has got caught up with the wrong crowd and knows something about the dead girl – but like most of the girls, she is not speaking. There is something treacherous going on with the laconically dangerous Johnno (Hugo Weaving), head of the drug squad, and the old sergeant. As the investigation slowly unravels the complex web of secrets, drugs and corruption that envelops the entire town, Jay takes the battle to Slaughter Hill for a final cleansing by fire and brimstone in a stunning re-visioning of the Mexican stand-off.

Jay is a cop caught between two worlds. Traditionally he would have occupied the role of the tracker, the ‘turncoat’, the native policeman – a man employed to track down and destroy his own people. Jay, the city-trained detective living on the ‘other’ side of town, is shunned and resented by the Aboriginal community – they distrust his worthy intentions and meet his enquiries with scornful silence. The first two Aboriginal kids he meets sum him up instantly: ‘Are you a copper? We kill coppers …’, they say, as one of them fashions a gun with his hand and mimics shooting him at close range. But Jay knows this community and understands how to negotiate a deal. Building trust, he lets one of the kids hold his gun and show off. He then swaps a broken mobile phone that the kid found near the house for some cash. The phone belonged to the dead girl. It is full of clues. The other coppers are wary of him and many of the whites do not attempt to disguise their hatred of the ‘Abo cop’.

This is not your classic black tracker tragic tale where both the tracker and the fugitives are predestined to die.

But this is not your classic black tracker tragic tale where both the tracker and the fugitives are predestined to die. Jay Swan cleverly negotiates these antagonistic worlds of a small-town community at war. In Aaron Pedersen’s contained and charismatic performance, he is an Indigenous cowboy superman, relentless in his pursuit of the truth as he circles the town, knocking on closed doors, peering into the darkness, unravelling small fragments of the past and not backing down in the face of ill-disguised civility. Jay finds a way between the community, the white copper establishment and his own broken family to achieve what others before have been unable to do – rise above narrative traditions that destroy empowered Indigenous men. The Indigenous engagement with police is rarely a happy one but in this story, the bad, inattentive cop model is overturned and we get the sort of committed Aboriginal cop that has been lacking on screen – someone who can bridge the various communities and earn the trust and respect of both black and white. Jay is a loner, a cowboy, a tough detective and a successful lawman able to operate across the various community cleavages. But at the end he still has a lot of work to do.

What genre?

When Australians do genre it is rarely only one: Mystery Road is billed as a murder mystery, a cowboy Western and an Indigenous crime thriller. Set in the remote outback of blood red horizons that stretch across endless featureless plains and sites of historical massacres (Slaughter Hill) – among a community barely disguising that they are at war, with morals shot to pieces – this is the Wild West. If the film was being evaluated as a murder-mystery thriller, some of the plot ellipses and the pacing could lead to discontent. But this stylish film only dances with genre. What in one film could be called ‘plot holes’ here are moments for audience’s imaginative engagement that allow for a play of possibilities that ratchet up the tension. Pedersen’s steely determination, cowboy hat and gunslinger strut operate as clear symbols, quietly highlighting that this is an epic revision of the black tracker narrative. The depictions of the magnificently endless horizons of the remote, scrubby landscape (Winton in Queensland) and the seediness of this otherwise sunnily overexposed town (Moree, NSW) are stunningly original. Seeing the town from the air in a series of topographical helicopter shots (reminiscent of Andreas Gursky) that track Jay’s car as it growls around the streets is a revelation. The photographic work (shot by Sen on a Red Epic digital camera) is powerful and assured. But most importantly, the film meshes the audiovisual gratifications with a spiralling, unravelling mystery where the malevolent tension keeps escalating.

Although Sen claims that he hasn’t done much genre filmmaking prior to Mystery Road, it is clear by examining his back catalogue that he is something of a crime auteur: his past two films most obviously explored the genre, although on closer examination most of his films, from the award-winning shorts (Dust, 2000; Warm Strangers, 1997) to his documentary works (Shifting Shelter series, 1995–2000; A Sister’s Love), deal with various forms of resistance, delinquency, marginality, social outcasts or the aftermath of crime and police apathy. His portrayal of crime is sophisticated and without easy moral judgements, demonstrating the relativity of criminal behaviour when seen from an Indigenous perspective.

Small crew, big ambitions

Sen eschews what he has dubbed the ‘circus mentality’ of big-crew filmmaking. In much of his work, he has committed to exploring an intimate and flexible approach, honed in documentary, where he has a direct connection between the ideas, the material, the camera, the landscape and the subjects. With Mystery Road he has moved away from the one-man-band extreme of Toomelah, but retained the key elements of control over the artistic vision and clarity of on-set communication, with credits as the writer, director, editor, composer and cinematographer (there was a small crew, production assistance and some data-wrangling in post-production). The project was developed in tandem with Pedersen, who was always going to play the lead role and was involved from the scripting stage. The move away from amateur actors to some of Australia’s most recognised stars (Hugo Weaving, Jack Thompson and Ryan Kwanten) in terrifically judged performances will ensure market visibility. It is a big-budget project, at least by Sen’s recent standards (A$2 million), but commercially appropriate for the potential audience.

Sen has moved away from the one-man-band extreme of Toomelah, but retained the key elements of control over the artistic vision and clarity of on-set communication, with credits as the writer, director, editor, composer and cinematographer.

Producer David Jowsey’s approach to distribution is being hailed as innovative, but he asserts that really it is a return to a more traditional model. Jowsey says, ‘the film is being distributed independently [Backlot Studios] on a limited number of screens through a straight fee for service ensuring that if the film makes a profit it will go directly to the filmmakers rather than the distributors.’ Because of Sen’s technical abilities they save a great deal of money and time on producing the marketing materials, as he can do poster artwork, the trailer and the stills. Jowsey expects the film to do better than his earlier film Mad Bastards (Brendan Fletcher, 2011) and cites a similar film, No Country for Old Men (Joel & Ethan Coen, 2007), that captured that balance between a commercial and arthouse audience that Mystery Road expects to emulate. Mystery Road has already sold to a US distributor (Well Go USA) highlighting the ongoing interest in the US for Indigenous Australian material. It will undoubtedly do well on the festival circuit as well as in its strategically limited Australian arthouse release in the later part of 2013.

This is a deeply satisfying film that combines modern and intelligent Indigenous themes within a cowboy mystery thriller. Mystery Road introduces a new Indigenous hero who notwithstanding his successes recognises that this is just beginning and that there is a lot of work that needs to be done. It is set in a stunningly epic landscape with a group of Australian actors at the top of their game. Ivan Sen is an auteur with a brave and clear artistic vision, and he is masterfully reinscribing traditional Australian narratives with an empowered Indigenous perspective.

http://www.mysteryroadmovie.com/

Endnotes

| 1 | See Peter Pierce, The Country of Lost Children: An Australian Anxiety, Cambridge University Press, 1999. |

|---|