Spread across smartphones, multiplexes, art houses, laptops, festivals and torrents, cinema is changing. But one thing remains the same: the problem of distribution for auteurist, independent and art cinema. The makers of small films have found themselves pushed out of mainstream cinema spaces by widely released, cross-marketed superhero and comic-book franchises. These tentpole films form the vanguard of the major studios’ push to consolidate the theatrical market in the midst of competition from new viewing outlets. For the team behind director and choreographer Stephen Page’s debut feature, Spear (2015), the problem of distribution is even more acute. How do you ensure that a dance-based film that is almost dialogue-free has a life in the context of a blockbuster-filled cinema market?

Coming of age in motion

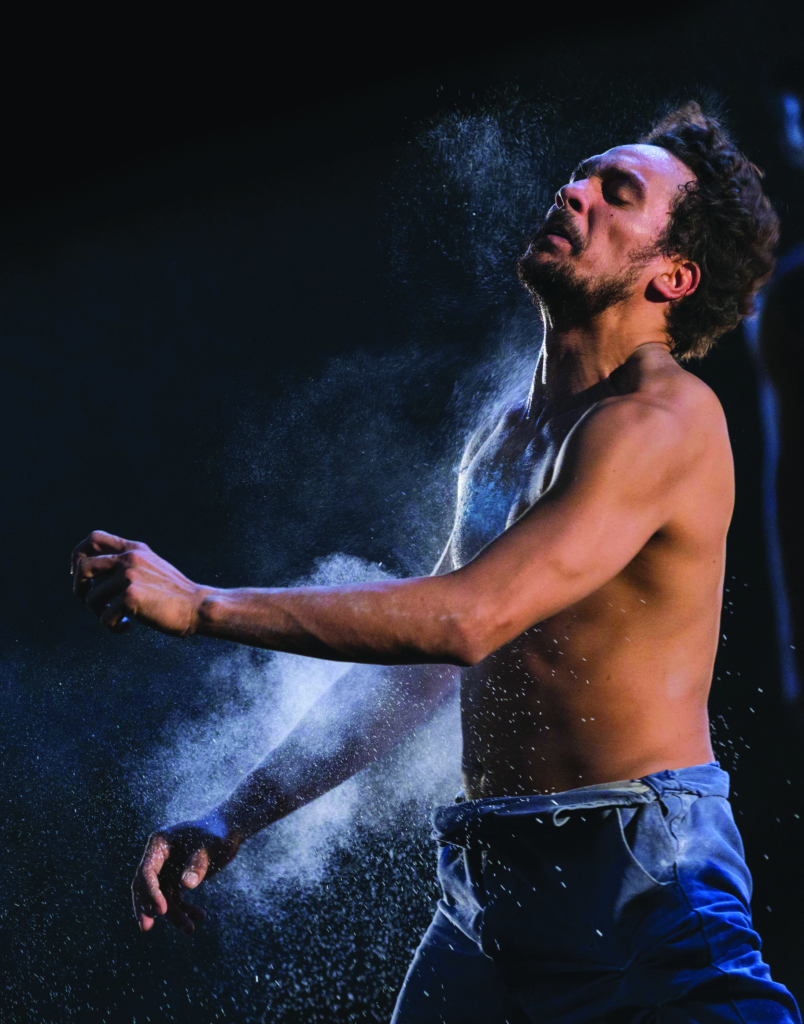

Spear is adapted from the Bangarra Dance Theatre’s original stage show, first performed in 2000. Its heavy focus on gesture and sound to create meaning and mood as well as its Indigenous themes and refusal to explain itself make it a challenging film, even for cinephile audiences. Whereas most films enunciate exposition, Spear opts for abstraction, letting the viewer feel their way through a loose narrative based more on emotional arcs than on tight plotting. Those arcs belong to protagonist Djali (played by Page’s son Hunter Page-Lochard), a young Indigenous man working out what it means to be Aboriginal in a hostile and urban whitefella world.

A general storyline about Djali’s coming of age unfolds visually and aurally by tracking his movement through a visibly Australian set of spaces. We begin with Indigenous spirits on a magnificent rocky coastline cleaved by an azure sky, before departing this spirit world and moving to a series of streetscapes, the narrative given forward motion by Djali’s walk. On his travels, he is followed by a protector of sorts, whom we are made to understand has come from the world of Indigenous spirits in the opening sequence. On his walk, Djali encounters a car crash – a great trauma of machines and torn steel – and dips into an underground tunnel by a railway station. There, he meets Suicide Man (Aaron Pedersen), who delivers a broken monologue almost directly to the camera, explaining his homelessness and alienation from his wife and children. The guts of the monologue are not verbal – Suicide Man is drunk and garbled. What is most clearly communicated is a depth of pain and loss. Though the film’s themes are spiritual, Suicide Man’s arc brings Spear’s most political themes to light: the destruction of Aboriginal people in a hostile sociopolitical system; the failure of services, charity and welfare; the sense of estrangement and rejection from an indifferent non-Indigenous world. Pedersen’s presence brings to mind two other films that similarly tackle the Indigenous plight of living between two worlds: Ivan Sen’s Mystery Road (2013) and Goldstone (2016).

The austerity of Spear’s settings … and the movement within them of Djali and his people clearly enunciate the film’s concept of existing between an Indigenous world of spirits and an inhospitable exterior world.

Many of the scenes in Spear are presented in abstracted settings: stage-like spaces in industrial contexts like Sydney’s Carriageworks and Cockatoo Island, where much of the indoor scenes were shot, which accentuate the narrative’s non-cinematic origins. The austerity of Spear’s settings – including a prison – and the movement within them of Djali and his people clearly enunciate the film’s concept of existing between an Indigenous world of spirits and an inhospitable exterior world. There are no domestic spaces, none of the usual settings we might expect of a coming-of-age drama – no bedrooms, kitchens, schoolrooms. Without the usual prop-loaded film sets, and with fairly generalist costume choices such as jeans and T-shirts, there are few clues as to where, exactly, Djali is and what is happening – deliberate ways of bringing the film’s open-endedness and narrative refusal into the level of art direction and set design. Likewise, without standard dialogue to hold onto, emotional beats are fortified instead through editing, as fluid cuts synchronise the music and choreography’s rhythms and flows. Apart from a few expansive establishing shots, the camera work remains decidedly human-scale, often just wide enough to capture groups of dancers, Djali among them.

With the exception of the Australian classic Jedda (1955) by Charles Chauvel, Page’s film makes few references to other works. Rather than an obvious continuation of existing cinematic currents, Spear is a steadfast departure from cinema history, an experiment using the talent and ideas of creative professionals whose expertise lies outside the film industry and who are finding new means of cinematic communication. What makes Spear an art film are its staunch refusal to conform to the established codes of narrative feature filmmaking, and its reliance on rhythm, non-verbal voices, blocking and music. In terms of cultural communication, this obtuseness allows for the presentation of information about ‘men’s business’ and Aboriginal law to a broader, non-Indigenous public in a way that is both authentic and intended to be felt rather than intellectualised.

Spear is a steadfast departure from cinema history, an experiment using the talent and ideas of creative professionals whose expertise lies outside the film industry and who are finding new means of cinematic communication.

Djali eventually moves back to more natural surrounds, with a series of female spirits guiding him to his culture, law and people. The film comes full circle on the coast, Sydney’s famous cityscape united with the wider ecology inside a larger visual frame. So, although Spear can be considered a narrative film with a beginning, middle and end, the precise nature of this narrative is not made explicit or literal. What we see is a coming-of-age story that simultaneously explores Indigenous masculinity, as part of the still-evolving dance-film canon.

Hitting the stage

As with many independent films, Spear’s distribution strategy began at film festivals, thereby pitching it to a traditional arthouse audience, before proceeding to a limited release in select ‘niche’ theatres. The 2015 Toronto International Film Festival played Spear in its ‘Discovery’ section, which gives audiences new experiences of world cinema and identifies directors to watch out for. Shortly after, the Adelaide Film Festival – having provided some production finance as part of its HIVE Fund program, in partnership with the Australia Council for the Arts, ABC Arts and Screen Australia – presented Spear’s Australian premiere as a gala screening in the filmmakers’ presence.

Beginning with film festivals was a riskier proposition than it may have seemed. Time-pressed screen critics can be notoriously sceptical of left-of-centre fare, and The Hollywood Reporter claimed that ‘more attendees at the first press-and-industry screening [at Toronto] walked out than stayed to the end’. That first review went on to describe Spear as ‘[b]eautiful but baffling […] it will impress initiates of the dance-on-camera scene but have little reach to other [audiences].’[1]John DeFore, ‘Spear: TIFF Review’, The Hollywood Reporter, 11 September 2015, <http://www.hollywoodreporter.com/review/spear-tiff-review-822273>, accessed 23 May 2016.Variety’s Eddie Cockrell was better able to make himself available to the film’s open-ended emotional drifts, describing the film as surmountably challenging to those willing to understand it – or, rather, willing to not understand it literally:

Audiences attuned to the film’s wavelength will respond fervidly, while distribs in search of something thematically unique and stylistically bold will take note. The film’s Toronto world preem should accomplish these tasks, gambolling the film to further fest play and beyond.[2]Eddie Cockrell, ‘Toronto Film Review: Spear’, Variety, 11 September 2015, <http://variety.com/2015/film/festivals/toronto-film-review-spear-1201590916/>, accessed 23 May 2016.

Reviews ranging from radiant to softly positive then followed in The Guardian,[3]Luke Buckmaster, ‘Spear Review – a Weird, Wonderful Milestone of a Dance Movie’, The Guardian, 19 October 2015, <http://www.theguardian.com/film/2015/oct/19/spear-review-a-weird-wonderful-milestone-of-a-dance-movie>, accessed 23 May 2016.The Sydney Morning Herald,[4]Jill Sykes, ‘Bangarra’s Spear Review: From Top End to Top of the Town’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 26 January 2016, <http://www.smh.com.au/entertainment/bangarras-spear-review-from-top-end-to-top-of-the-town-20160125-gmd874.html>, accessed 23 May 2016. The Australian[5]David Stratton, ‘Reviews: Eye in the Sky; Spear; London Has Fallen’, The Australian, 19 March 2016, <http://www.theaustralian.com.au/arts/review/reviews-eye-in-the-sky-spear-london-has-fallen/news-story/161a34d2438618e4353a4defbadd15cf>, accessed 23 May 2016. and younger, more niche presses like Junkee.[6]Emma Jukić, ‘Introducing Spear: A Must-see Film About Indigenous Experience in Modern Australia’, Junkee, 10 March 2016, <http://junkee.com/introducing-spear-must-see-film-indigenous-experience-modern-australia/74560>, accessed 23 May 2016.

The launch for Spear’s limited release this year took a different tack: distributor CinemaPlus opted to premiere at the Sydney Festival, a large mainstream interdisciplinary arts event held in January. Rather than screening at a commercial cinema, Spear was shown to an art-inclined audience in a traditional dance space – Bangarra’s home theatre – at the Opera House, just downstream from Cockatoo Island. At this event, Page told the audience:

What I didn’t want to do was forget the integrity of an audience watching a Bangarra film live, and how to take the spirit of that and put it into the medium of celluloid. I wanted to make sure that spirit continued on […] to cross that over into film. It’s deliberate: it’s the film I wanted to make, and I’m so proud that I stuck to that form and that idea.

Producer John Harvey then made a personal plea: ‘It’s a small film, and it really does depend on word of mouth from you.’ A month later, Spear would be taken beyond ready-made spaces altogether, and presented to an Indigenous audience during an open-air screening in the Northern Territory. ‘We’ve got a blow-up theatre screen,’ Page had said at the Sydney Festival. ‘We’ll give Spear back to the community.’

A national limited release followed in the usual arthouse locations like Dendy in Sydney, Melbourne’s Cinema Nova, Nambour Arthouse Cinema, and the National Film and Sound Archive of Australia’s Arc Cinema in Canberra. Alongside this theatrical season were a series of more ‘niche’ screenings at varied venues and events, often with Harvey appearing in person or on Skype for discussions with audiences, including the Museum of Old and New Art’s Festival of Music and Art (MONA FOMA) in Tasmania; the Burrinja Theatre and the Gasworks Arts Park Backyard Cinema, both in Victoria; the Screen Café in Parramatta, New South Wales; Geraldton’s Film Harvest and Leederville’s Luna Outdoor Cinema, both in Western Australia; Darwin’s Deckchair Cinema; and Country Arts SA’s Black Screen events. As the final part of this distribution jigsaw, the film was made available on Tugg, a cinema-on-demand platform catering for keen, under-served audience members who can ask theatres to host additional screenings of offered titles if enough viewers pre-purchase a ticket.

The right moves

What are the lessons here for Australian filmmakers? What other creative solutions might help small, unusual films find a life both inside and outside the cinema space? The guiding intelligence of Spear’s outreach was to present the film in different spaces for different audiences in a targeted manner; a hybrid film needs hybrid distribution. This approach thus saw Spear move systematically from film-festival audiences and critics, to art and dance audiences such as those at the Sydney Festival, before moving into directed general exhibition as part of a limited release in cinemas.

Some critics have aligned Spear with the classic musical West Side Story (Jerome Robbins & Robert Wise, 1961),[7]See, for example, Cockrell, op. cit. in which choreography forms a core component of cinematic communication. There are also discernible parallels with Page’s work on Robert Connolly’s anthology film The Turning (2013), for which he directed a largely non-verbal story of Indigenous kinship against a natural environment. But I think Spear finds its most surprising parallel in Quentin Tarantino’s recent The Hateful Eight (2015). That film, a revisionist western, was distributed in a roadshow style as ‘The 8th Film by Quentin Tarantino’. Upon buying a ticket, cinema-goers were given a colour program containing glossy behind-the-scenes photos and notes on the film’s cast, format, theatrical release and production history. Eschewing digital projection, The Hateful Eight was shown in select cinemas on a 70mm film print, prefaced by a three-minute musical overture by composer Ennio Morricone and cleaved by a brief intermission, which gave cinema-goers time to fetch a cup of tea and swap opinions before the film had even ended. This exhibition approach was all about context: creating a series of frames and filters for audiences to interpret the film, and extending the film’s sense of a bloody good time into the manner of its presentation. This unique form of exhibition happened at only six theatres in Australia, a week before the film’s regular, digitally processed release at a larger number of theatres.[8]Campbell Simpson, ‘The Six Best Cinemas to Watch Tarantino’s The Hateful Eight in Australia’, Gizmodo, 15 January 2016, <http://www.gizmodo.com.au/2016/01/the-best-cinemas-to-watch-tarantinos-the-hateful-eight-in-australia/>, accessed 2 May 2016.

As with Spear, this kind of event-style engagement is a way in which filmmakers and distributors are making cinema-going indispensable and rarefied again in the age of streaming and digital disposability. Going back through film history, the precedent for event-style presentations is embodied by the aforementioned roadshow-release method in the US, which saw the delivery of such films as Gone with the Wind (Victor Fleming et al., 1939) and Ben-Hur (William Wyler, 1959), whose screenings were also cushioned by an overture, an intermission and a big colourful program. In this roadshow approach, the feature film was only one part of the evening’s events, and the cinema was a revered place for a glorious night out.

Event-style exhibition … emphasises the materiality of the cinema space and, often, the physical presence of the filmmaker, cast and crew – all to engage the core of what it means to be a member of the audience.

Today, the cinema is more usually a place for public solitude. A sameness has crept across the moviegoing experience: ostensibly arthouse chains like Dendy have adopted a multiplex business model, upgrading their cinemas with the same plush seats, upselling food and wine combos at the front desk, and programming the newest Superman instalments alongside more esoteric titles from the film-festival circuit. Event-style exhibition, however, emphasises the materiality of the cinema space and, often, the physical presence of the filmmaker, cast and crew – all to engage the core of what it means to be a member of the audience. This manner of presenting a film transforms a screening into a show – one that is bound by a specific moment in time – and returns cinema-going to an in-the-moment proposition.

Refocusing on the tangible moments of the film-viewing experience in an era of all-access digital distribution is more than a value-adding marketing proposition: it creates an entirely different path around a film through which an audience member comes to their sense of what watching a film encompasses. Event-style engagements are therefore emblematic of exhibition and distribution’s ability to produce a sense of occasion, specifically affecting the audience’s experience of a film and the culture of discussion and socialising that forms around cinema.

In these moments, the aesthetics of exhibition match a film’s content and themes with its viewing spaces; Spear’s outdoor Northern Territory outing, its projection in the Bangarra theatre and its gala screenings attended by its filmmaking team exemplify this. For Spear, exhibition and distribution were not just ways to sell tickets and recuperate the production spend – they functioned as ways to contextualise the film, to give it a space, a home and a setting for audiences to make sense of what is on screen. This contextualisation was all the more important, given the film’s refusal to direct audiences as to how to interpret it.

A film may be a piece of celluloid or a file on a hard drive, but it also lives in the spaces and contexts where it is exhibited and distributed. The way a film exists in an exhibition setting, the manner in which it is delivered to a live audience, how the feeling and the reception of the work changes from place to place – all these things become part of how cinema wraps itself around viewers and the means by which a text is brought to life.

As a unique narrative and visual text, each film requires a specific distribution and exhibition plan to best deliver it to its audience and to contextualise its reception. Spear’s distribution journey is very much like Djali’s: he is finding his own feet, his own voice and his own way between two worlds. Most publicly funded films must play in the theatrical market to attain production funds from Screen Australia, but there are other places for a screen text to dance through and extra-cinematic spaces to grow in and inhabit. Despite the history of roadshow presentations, event-style distribution in Australia is still being consolidated as a way to connect with audiences in a fractured digital-distribution landscape.

In Spear’s case, distribution is not complete – the film is yet to be released on DVD, television and online. Until then, the lessons for the makers of small, independent films will continue to unfold.

Endnotes

| 1 | John DeFore, ‘Spear: TIFF Review’, The Hollywood Reporter, 11 September 2015, <http://www.hollywoodreporter.com/review/spear-tiff-review-822273>, accessed 23 May 2016. |

|---|---|

| 2 | Eddie Cockrell, ‘Toronto Film Review: Spear’, Variety, 11 September 2015, <http://variety.com/2015/film/festivals/toronto-film-review-spear-1201590916/>, accessed 23 May 2016. |

| 3 | Luke Buckmaster, ‘Spear Review – a Weird, Wonderful Milestone of a Dance Movie’, The Guardian, 19 October 2015, <http://www.theguardian.com/film/2015/oct/19/spear-review-a-weird-wonderful-milestone-of-a-dance-movie>, accessed 23 May 2016. |

| 4 | Jill Sykes, ‘Bangarra’s Spear Review: From Top End to Top of the Town’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 26 January 2016, <http://www.smh.com.au/entertainment/bangarras-spear-review-from-top-end-to-top-of-the-town-20160125-gmd874.html>, accessed 23 May 2016. |

| 5 | David Stratton, ‘Reviews: Eye in the Sky; Spear; London Has Fallen’, The Australian, 19 March 2016, <http://www.theaustralian.com.au/arts/review/reviews-eye-in-the-sky-spear-london-has-fallen/news-story/161a34d2438618e4353a4defbadd15cf>, accessed 23 May 2016. |

| 6 | Emma Jukić, ‘Introducing Spear: A Must-see Film About Indigenous Experience in Modern Australia’, Junkee, 10 March 2016, <http://junkee.com/introducing-spear-must-see-film-indigenous-experience-modern-australia/74560>, accessed 23 May 2016. |

| 7 | See, for example, Cockrell, op. cit. |

| 8 | Campbell Simpson, ‘The Six Best Cinemas to Watch Tarantino’s The Hateful Eight in Australia’, Gizmodo, 15 January 2016, <http://www.gizmodo.com.au/2016/01/the-best-cinemas-to-watch-tarantinos-the-hateful-eight-in-australia/>, accessed 2 May 2016. |