There are two ways to watch Kriv Stenders’ Red Dog films. The first is with cynicism at full throttle – in that case, you’ll most likely have a lousy time, and you have my sympathies. The second is to take them on their own terms and embrace them for what they are. The original Red Dog (2011) took the various tall tales about a remarkable hound that roamed around mining communities in Western Australia and wove them into a self-conscious legend. The follow-up, Red Dog: True Blue (2016), begins with a father (Jason Isaacs) and his kids watching Red Dog in the cinema. One of the kids catches Dad crying at the film’s climax and, when he’s being put to bed, he asks his father what had caused him to burst into tears. After a bit of prodding, Dad reveals that Red was actually his dog when he was young – and that the pup’s real name was actually Blue.

Cue: secret origin story.

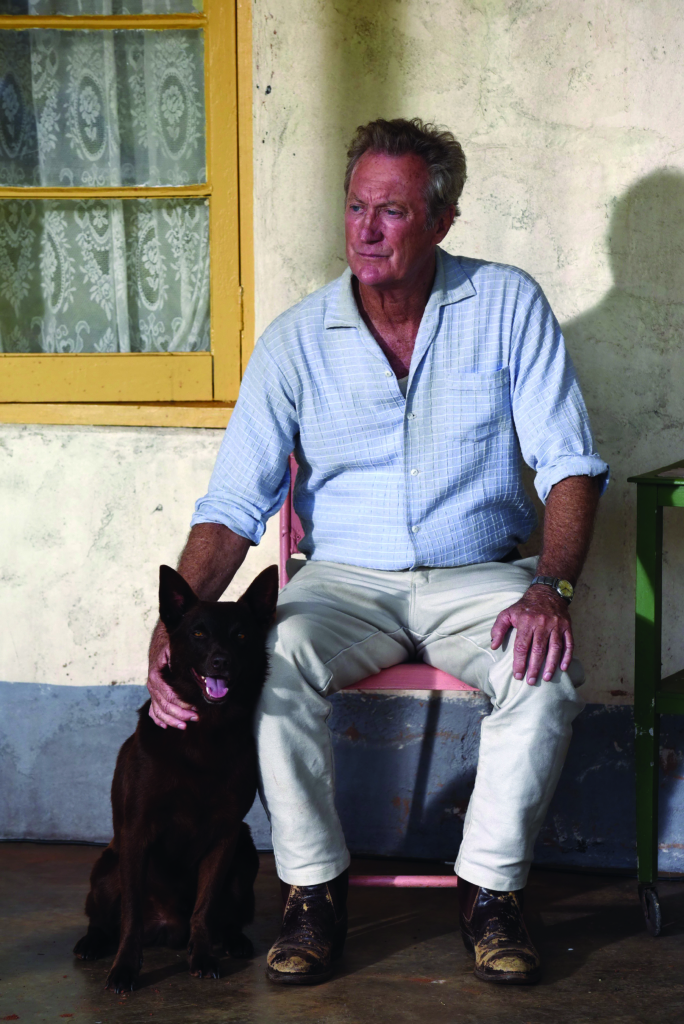

Dad’s name is Michael ‘Mick’ Carter and, when he was a boy (played by Levi Miller), his mother suffered a breakdown following his father’s death. She’s confined to an institution, and he’s shipped off to the care of his gruff grandpa (Bryan Brown). Grandpa has an enormous farm out in Pilbara country, where the dirt is red and the sky goes on forever. There’s no-one for Mick to really be friends with, though, and it’s only when a cyclone rages across the landscape that Blue is discovered, almost like some miraculous Moses beached halfway up a tree. Mick rescues the dog and, naturally, they become inseparable, with the rest of the film depicting their adventures.

It’s important to note that, as with its predecessor, True Blue is not remotely interested in presenting us with the Australia of reality. And that’s fine. Rather, like the worlds evoked by Crocodile Dundee (Peter Faiman, 1986), Strictly Ballroom (Baz Luhrmann, 1992), The Castle (Rob Sitch, 1997) and, the big daddy of them all, Australia (Baz Luhrmann, 2008), there’s a mythic quality to the film that a lot of people mistake for corniness. You can understand why, of course. Everything about these films is done in broad strokes. The humour is broad. The faces are broad. The ambitions are broad (you’ll note that all of them are box-office hits). But that’s because they’re doing fairytales, and it’s extremely tricky to do fairytales with a straight face. We live in cynical times, when irony is king. Put a foot wrong and it’s very easy to dismiss a deliberate archetype (such as Brown’s Grandpa) as a shallow stereotype.

Part of the reason True Blue’s strategy works, though, is that – like the original – it’s carefully set in a bygone age. We can believe in Mick, Grandpa and the amazing adventures of Blue because they exist in an Australia that simply doesn’t exist anymore. The film takes place in 1967, a time when we can kid ourselves that men were more manly, that dogs could be discovered halfway up trees, and that mythic events could still transpire in out-of-the-way places if you looked hard enough. Like an ad for the National Party – and True Blue is ravishingly photographed – we’re encouraged to think of Grandpa’s station as innocent, simple and beautiful. It’s a place where hard, honest toil is rewarded, a place to literally escape from confusing, shameful, unsettling things like familial mental illness.

Like the worlds evoked by Crocodile Dundee, Strictly Ballroom, The Castle and, the big daddy of them all, Australia, there’s a mythic quality to the film that a lot of people mistake for corniness.

But the more important reason the film works is that, well, there’s nothing cynical about the way the story is told. Which is not to imply the filmmakers don’t know exactly what they’re doing. Both of the Red Dog films are full of jokes, and the fact that they’re presented as tall tales means we’re never meant to take them entirely seriously. Yet, when the chips are down and these mythic films reach their Big Iconic Moments, there’s no winking.

And, as a country boy from way back, I have to tell you: that’s refreshing. Not because I want the outback and its people mythologised any more than they already are, but because, in an age of Trump, Brexit and the resurgence of Hansonism, it strikes me that one of the reasons that rural communities have been gunning for revolution is the way they’re always depicted in the media as bumpkins, murderers, bigots or clods. I’m not denying such people exist – of course they do and, aside from the murderers, I’ve known examples of every type. What may surprise you is that, despite their faults, they’re still basically good people, precisely because they’re richer than the one-word rural stereotype. They’re casually racist until their sons marry a Filipino or their daughters marry a Pacific Islander. They’re homophobic until a pair of lesbians takes over the struggling general store and makes it somewhere worth shopping again. They’re suspicious of climate change but, because nobody watches the weather like farmers, they know the seasons have become progressively drier over the last forty years. In short, there’s more to these people than how they vote every electoral cycle – and, when I see a film like True Blue, I see the best of them reflected there. The daggy jokes. The people struggling to do their best in tough circumstances. The straightforwardness. Is it any wonder, then – despite the critical sniffiness that often attends them – that these mythic films do so well, especially out in the regions?

In choosing to set their story in 1967, the filmmakers are both celebrating and witnessing the last gasp of that bygone age … For a twenty-first century viewer – for whom the film already looks like the good old days – the message is clear: nostalgia ain’t what it used to be.

What’s really interesting is that, in choosing to set their story in 1967, the filmmakers are both celebrating and witnessing the last gasp of that bygone age. His cattle station may look like a perfect edifice but, in one scene, Grandpa looks around during a party and remarks, ‘This is how it looked in the old days. When the camp was full. Smelled of sweat and hard work.’ The irony is that even a film that seems so nakedly nostalgic can declare that the good old days are long gone. For a twenty-first century viewer – for whom the film already looks like the good old days – the message is clear: nostalgia ain’t what it used to be.

There’s also an ever-present chill in the air, the kind that ultimately killed off the dinosaurs. The young folk are caught up in the two sociopolitical cross-currents of the time: Bill (Thomas Cocquerel) bears the scars of a Vietnam tour, while his would-be girlfriend, Betty (Hanna Mangan Lawrence), yearns to join the Summer of Love. The filmmakers even insist on a rendition of Bob Dylan’s ‘The Times They Are a-Changin’’ at one point just to be sure you haven’t missed their theme and, while it’s the closest they come to hitting a bum note, the overall guileless tone ensures they just get away with it. On the more subtle side of the ledger is the fact that – despite the cast largely conforming to the outback Anglo-Saxon stereotype – the filmmakers are still careful to include an actor with an Asian background, several Aboriginals in supporting roles, and even sneak in two characters that are quietly gay. Couple this with Betty’s determination to define herself outside the traditional ‘girlfriend’ or ‘wife’ role, and it’s clear the green shoots of progressivism are peeking through the red dirt.

The film also plays a nuanced game regarding land rights, with the story maintaining an ongoing thread about who owns the station and what happens when ‘traditional’ owners are disrespected. Mick is careful to point out that the station rests on Aboriginal land and, when he later disrespects one of the elders by ‘taking his soul’ from its resting place, disaster strikes. Rather than retribution falling on Mick, however, fire rages towards the station itself, and it’s only Mick’s realisation that he’s to blame that saves the day. As with Mick Dundee’s (Paul Hogan) ‘bushman tricks’ or Nullah’s (Brandon Walters) ability to stop charging cattle in Australia, it’s during moments like these that True Blue walks its finest line. Nobody wants to see Aboriginal customs disrespected and, as the film sends its hero into a literally mythic cave to complete his journey, I did worry that I was watching a white man’s version of black spirituality.

The good news is that, although the result is hardly Ten Canoes (Rolf de Heer & Peter Djigirr, 2006), I suspect that’s partly the point. Nobody mentions it in the film, but 1967 was the year when the referendum was held to declare Aboriginals full citizens[1]See ‘The 1967 Referendum – Fact Sheet 150’, National Archives of Australia, 2017, <http://www.naa.gov.au/collection/fact-sheets/fs150.aspx>, accessed 1 May 2017. – and this political sea change is reflected in the character of young jackaroo Taylor Pete (Calen Tassone) beginning to think about campaigning for land rights. We don’t see the political or cultural complexities of why he’d elect to follow such a path, but that’s because it would jar with the mode of storytelling the filmmakers have chosen to adopt. As the date suggests, we’re at the birth of a moment, a hinge point in Australian history, all viewed through the eyes of a whitefella boy. It’s enough that Mick comes to understand the link between Aboriginal people and the land when he takes the old man’s soul, and it’s enough when Taylor Pete rubs red dirt on Mick’s hands at the story’s end, linking him to the place forever.

Complicating the theme further is the appearance of mining magnate Lang Hancock (John Jarratt). Whereas the thread about Aboriginal land rights is presented as a good thing – or, at the very least, something farmers need to coexist with – Lang is depicted as a different kind of change altogether. At first, it appears that he’ll simply be presented as a kind of historical celebrity, albeit one that Blue takes an atypical dislike to. However, he then proceeds to tell Grandpa that his farm is going to be bought out in ‘the public interest’, and we realise that Lang’s been chosen specifically to represent the new threat facing landowners: bullying miners.

Of course, the notions of Aboriginal land rights and farmers’ land rights are hardly the same thing – but, as a film like The Castle cheekily points out, the ‘vibe’ of a personal connection to property can definitely … well, feel similar. The real-world Hancock certainly discerned this same vibe, remarking:

Nothing should be sacred from mining whether it’s your ground, my ground, the blackfellow’s ground or anybody else’s. So the question of Aboriginal land rights and things of this nature shouldn’t exist.[2]Lang Hancock, quoted in Michael Coyne & Leigh Edwards, The Oz Factor: Who’s Doing What in Australia, Dove Communications, Melbourne, 1980, p. 68, emphasis in original.

Nor was he shy, as his portrayal in True Blue demonstrates, about demanding that government support his cause. Once again, 1967 is presented as a hinge moment, with the arrival of Big Mining the first straw in the wind that has ultimately culminated in the strange political storm that is the coal-seam-gas industry versus the Lock the Gate Alliance. On one side, you have Barnaby Joyce, leader of the National Party and supposed champion of country folk, cosying up to Hancock’s daughter, Gina Rinehart.[3]See Fergus Hunter, ‘Barnaby Joyce Grilled over Gina Rinehart Donations’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 7 September 2016, <http://www.smh.com.au/federal-politics/political-news/barnaby-joyce-grilled-over-gina-rinehart-donations-20160906-grafbm.html>, accessed 1 May 2017. On the other, you have farmers – generally conservative by nature, but not terribly keen on their water being flammable – alongside the Greens and shock jocks like Alan Jones.[4]See Phillip Coorey, ‘At the Coalface: Jones and Greens Together in Mining Fight’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 20 October 2011, <http://www.smh.com.au/environment/at-the-coalface-jones-and-greens-together-in-mining-fight-20111019-1m85u.html>, accessed 1 May 2017. Strange bedfellows indeed.

But then, ultimately, it’s these kinds of complications beneath the surface of True Blue that make it so rewarding. It’s a film that feels intensely nostalgic – but, as anyone familiar with the roots of that word is aware, ‘nostalgia’ is a compound of the Greek terms for homecoming (nostos) and pain (algos). Thus, rather than the sepia tinge of a historical never-never land, True Blue presents us with a genuinely wrenching moment in time and refuses to shy away from the fact that change can be a positive thing. It’s a film that begins with a man crying and not wanting to admit it, and ends with a boy yelling at a dog to leave him alone when he actually wants it to stay. Naturally, it’s going to get to you if you’re a dog lover, but it was the penultimate scene – when Mick says goodbye to Grandpa – that really snuck under my defences. The old bloke is too inhibited to hug or kiss him, settling for a handshake instead, and I’m sure that some critics would actually prefer such a ‘subtle’, emotionally constipated response. The thing is, though, having known so many men like that – so trapped by their own silly rules of masculine behaviour – it’s this failure as a human being that’s more heartbreaking than Mick’s departure. Much like Mr Stevens (Anthony Hopkins) in The Remains of the Day (James Ivory, 1993) or Newland Archer (Daniel Day-Lewis) in The Age of Innocence (Martin Scorsese, 1993), you want to shake these men by the lapels, to impress upon them that it’s okay to step outside the manners and mores they’ve spent their whole lives observing. That it’s okay to speak up, to show emotion. To cry.

But perhaps that’s why people like that need films like Red Dog: True Blue. They need to go and see films like this so they can cry quietly in the dark. And then, when the lights come on, they can pretend it never happened. Until someone asks them to tell a story all about the pain that is homecoming.

https://village.roadshow.com.au/red-dog-true-blue

Endnotes

| 1 | See ‘The 1967 Referendum – Fact Sheet 150’, National Archives of Australia, 2017, <http://www.naa.gov.au/collection/fact-sheets/fs150.aspx>, accessed 1 May 2017. |

|---|---|

| 2 | Lang Hancock, quoted in Michael Coyne & Leigh Edwards, The Oz Factor: Who’s Doing What in Australia, Dove Communications, Melbourne, 1980, p. 68, emphasis in original. |

| 3 | See Fergus Hunter, ‘Barnaby Joyce Grilled over Gina Rinehart Donations’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 7 September 2016, <http://www.smh.com.au/federal-politics/political-news/barnaby-joyce-grilled-over-gina-rinehart-donations-20160906-grafbm.html>, accessed 1 May 2017. |

| 4 | See Phillip Coorey, ‘At the Coalface: Jones and Greens Together in Mining Fight’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 20 October 2011, <http://www.smh.com.au/environment/at-the-coalface-jones-and-greens-together-in-mining-fight-20111019-1m85u.html>, accessed 1 May 2017. |