Innumerable pages of academic literature have been devoted to making sense of the Cronulla Riots; the events have seemingly been interpreted through every lens imaginable. Scholars have tapped into the tensions the confrontation exposed regarding issues of national identity, belonging and competing masculinities.[1]See, for example, Nahid Afrose Kabir, ‘The Cronulla Riots: Muslims’ Place in the White Imaginary Spatiality’, Contemporary Islam, vol. 9, no. 3, September 2015, pp. 271–90; Scott Poynting, ‘What Caused the Cronulla Riot?’, Race & Class, vol. 48, no. 1, July 2006, pp. 85–92; and Scott Poynting, Paul Tabar & Greg Noble, ‘Looking for Respect: Lebanese Immigrant Young Men in Australia’, in Mike Donaldson et al. (eds), Migrant Men: Critical Studies of Masculinities and the Migration Experience, Routledge, New York & London, 2009, pp. 135–53. A commonly cited instigation for the riots is white Australians’ discussion of ‘those wogs’ on ‘our beaches’, harassing ‘our women’ in ways that are altogether ‘un-Australian’.[2]See Ryan Barclay & Peter West, ‘Racism or Patriotism?: An Eyewitness Account of the Cronulla Demonstration of 11 December 2005’, People and Place, vol. 14, no. 1, 2006, pp. 75–85; and ‘Case Study Four: The Cronulla Riots – The Sequence of Events’, Reporting Diversity website, <http://www.reportingdiversity.org.au/cs_four.html>, accessed 1 November 2016. Additionally, a number of creative works have attempted to weigh in on the discussion, including Anne Zahalka’s The Girls #2, Cronulla Beach, a photograph that mirrors her earlier series centring on Bondi,[3]‘The Girls #2, Cronulla Beach’, Art Gallery of New South Wales website, <https://www.artgallery.nsw.gov.au/collection/works/398.2011/>, accessed 1 November 2016. and Suzie Miller’s All the Blood and All the Water, a play inspired by real conversations the playwright had with rioters on both sides of the ostensible divide.[4]Louise Schwartzkoff, ‘Mateship up Against Tribal Mentality’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 29 April 2008, <http://www.smh.com.au/news/arts/mateship-up-against-tribal-mentality/2008/04/28/1209234762131.html>, accessed 1 November 2016. It is amid all this conversation that Abe Forsythe’s Down Under (2016) attempts to situate itself, bringing a comedic dimension to a much-discussed and highly polarising issue. Certainly, some reviewers have considered the film’s comedic approach an effective way to lighten a significantly heavy topic,[5]See, for example, Luke Buckmaster, ‘Down Under Review – Gusty Black Comedy About Cronulla Riots Tackles Racism Head on’, The Guardian, 16 June 2016, <https://www.theguardian.com/film/2016/jun/16/down-under-review-gutsy-black-comedy-about-cronulla-riots-tackles-racism-head-on>, accessed 1 November 2016; and Paul Byrnes, ‘Down Under Review: Cronulla Riots Comedy a Daring, Welcome Blast of Fresh Air’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 11 August 2016, <http://www.smh.com.au/entertainment/movies/down-under-review-cronulla-riots-comedy-a-daring-foulmouthed-blast-of-fresh-air-20160810-gqp1oc.html>, accessed 1 November 2016. yet such a privilege may only be accessible if you’re a white male in Australian society.[6]For a contrasting perspective, see Amal Awad, ‘Down Under Review: Cronulla Riot Racism Comedy Swings, Misses’, SBS Movies, 7 August 2016, <http://www.sbs.com.au/movies/review/down-under-review-cronulla-riot-racism-comedy-swings-misses>, accessed 1 November 2016.

The film was both written and directed by Forsythe, whose earlier credits include appearances in TV series Always Greener, miniseries Marking Time and the 2003 comedy feature Ned (which he also directed). Described as a ‘black comedy’ and set in the aftermath of the Cronulla Riots, Down Under is ‘the story of two carloads of hotheads from both sides of the fight destined to collide’.[7]StudioCanal, Down Under press kit, 2016, p. 2. Beyond this, the film is a difficult text to explore, primarily because it sets out to do so much yet achieves so little. In his director’s statement, Forsythe earnestly puts forward a premise that is sociologically sound: ‘As a nation’, he suggests, ‘we all tolerate or participate in an informal, throw-away kind of racism […] We think it’s harmless so we don’t actually do anything about it.’[8]Abe Forsythe, ‘Director’s Statement’, in ibid., p. 4. His introduction leaves us thinking that his film will be a challenge to the kinds of everyday microaggressions experienced by minorities, or a broader discussion of race and racism in contemporary Australia. The sad reality, however, is that, despite all its good intentions, Down Under fails to shed new light, or even reflect old intelligent glimmers, on a widely debated issue. Instead, it reveals its lack of deep consideration, which is disappointing for a satire on this topic. As for the comedy, the film often misses the mark by failing to contextualise the levity during moments of excruciating narrative discomfort.

Down Under opens with a series of clips showing the real-life Cronulla Riots, then cuts to Hassim (Lincoln Younes) expressing a desire to turn his life around. He appears to be working diligently, studying hard and generally keeping out of trouble, when his old friend Nick (Rahel Romahn) turns up, enquiring as to where Hassim’s younger brother might be. Afraid his sibling might be one of the riot’s casualties, Hassim reluctantly joins Nick and wannabe rapper D-Mac (Fayssal Bazzi) to head to The Shire, where they will seek retaliation for the ‘Leb- and wog-bashing day’. Along the way, the boys pick up Nick’s uncle Ibrahim (Michael Denkha), a devout yet eccentric Muslim.

Despite all its good intentions, Down Under fails to shed new light, or even reflect old intelligent glimmers, on a widely debated issue. Instead, it reveals its lack of deep consideration, which is disappointing for a satire on this topic.

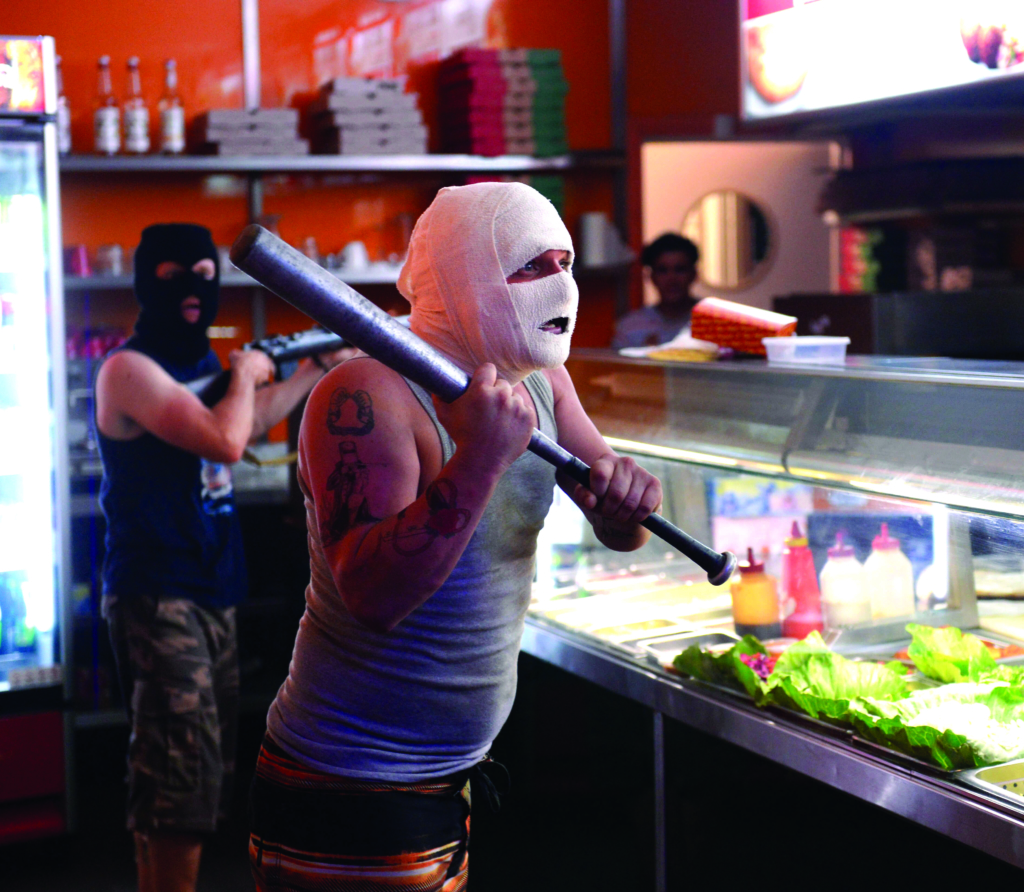

Also out on the hunt is an equally odd troupe consisting of Jason (Damon Herriman), the only member of his cohort who seems genuinely determined to seek revenge; the dim-witted Ditch (Justin Rosniak), who spends the majority of the film with a bandage wrapped around his head, and declares his love for Ned Kelly through his collection of tattoos; Shane (Alexander England), better known as ‘Shit Stick’, who desperately wants nothing to do with the ‘wog-bashing’; and Shane’s younger cousin Evan (Christopher Bunton), who has Down syndrome and provides a voice of reason amid the chaos.

The hooliganism and unrelenting bickering of the two groups are the source of much of the film’s hilarity. And, while Hassim, Shane and Evan each express hesitations about violently attacking others, their companions prove less concerned by the brutality of this approach. In an especially touching scene – one of few that affect a sense of genuineness – Evan asks Shane during a car chase whether he should dislike his friend, who happens to be Lebanese, even though he’s really nice. Shane pauses, considers the logic behind Evan’s question, then concedes that chasing ‘Lebs’ around is an utterly stupid pastime. This, of course, doesn’t prevent the film’s inevitable confrontation on a deserted beachside cliff-face in the dark of night, during which the two groups maim one another mercilessly. At the conclusion of this scene, Hassim receives a call from his brother, who lets him know he’s in the Gold Coast with some ‘chicks’ and apologises for not being in touch earlier because his phone had died. The revelation that his brother is okay brings with it the realisation that Hassim’s (reluctant) involvement in the chase through The Shire – originally spurred by feelings of kinship – was, in fact, for nothing.

Undoubtedly, here, the film is attempting to conjure some kind of ironic hilarity: while one brother was being beaten on Sydney’s glorious beaches after people who look like him were seen approaching women who didn’t look like them, the other was frolicking on Australia’s northern beaches with ‘chicks’ and having the time of his life. The audience, however, cannot feel the full force – or, perhaps, any force – of this irony because the concept is poorly translated. It is overacted, the point is laboured and didactic, and the comedy is lost. Indeed, as a comedy so adamant to reveal the harsh realities of racism, Down Under does so only with the insight of a primary school Harmony Day play: its conclusion is simply that we are all the same, though perhaps sometimes misunderstood. The film’s trailer even boasts the tagline ‘Culture divided them, ignorance brought them together’. I appreciate the intention behind using humour, particularly as self-deprecation – laughing at our own expense – is a quintessentially Australian tendency. Unfortunately, in a story that pits two culturally distinct groups against one another, the ‘our’ unavoidably becomes divided into a ‘them’ and an ‘us’. Laughing at race-based conflict only works when there is an acknowledgement of society’s unequal distribution of power, and when humour is directed at groups who aren’t historically marginalised – neither of which Forsythe’s film does.

As a comedy so adamant to reveal the harsh realities of racism, Down Under does so only with the insight of a primary school Harmony Day play: its conclusion is simply that we are all the same, though perhaps sometimes misunderstood.

Moreover, Down Under ignores the cultural differences and structural inequalities that lead to the kind of aggression we witnessed at Cronulla, instead reducing the encounter to one in which groups of incompetent young men merely assert their masculinity. The film’s most notable depiction of this problematic machismo sees Shane’s father, Graham (Marshall Napier), hand him a shotgun for use when shooting ‘wogs’. Shane and Evan express reluctance, but are pressured into joining the ‘hunt’; both feel the only way to prove their own worth is to prove that others are worthless. Yet, without contextualising how and why these young men feel the need to assert their masculinity in aggressive ways, and how and why their motivations differ from those of their disenfranchised minority counterparts, the film places both groups on equal footing – thereby erasing the realities of historical and political disadvantage. Down Under even verges on humour that is, unfortunately, quite offensive. The later revelation that Ditch’s covered face is hiding a Ned Kelly–inspired tattoo that resembles a burqa detracts from the cultural significance of this form of dress for women in certain parts of the world. Making jokes about the way minorities in the West uphold their cultures’ traditions harks back to the days of overt racism. This kind of comedy doesn’t ‘bring us together’; it marginalises and alienates groups that are already marginalised and alienated, particularly with respect to outward appearance. It gives the ignorant licence to laugh at things they don’t like or understand, without necessarily interrogating why. And, while good comedy can certainly make us feel uncomfortable, it should also encourage us to explore the reasoning behind our discomfort.

Arguably, part of the reason Down Under falls flat is that its creative team is itself not particularly diverse. For its multicultural cast, Down Under ought to be commended; it demonstrates that actors from ‘Other’ backgrounds are not that difficult to come by, and that inclusion is indeed possible. Forsythe might grasp that broader society has a long way to go in terms of minority inclusion and understanding – this is evident in his film’s underlying concept – but he seems to have neglected how this is reproduced in the very industries we engage with daily. In the case of cinema, it is not enough to simply have actors of ‘Middle Eastern appearance’ mouth lines written for them; for a film like Down Under to be successful – in storyline, in humour and in combating the racism it condemns – the key creatives need to possess the very voices that they write. To do otherwise is to have an underrepresented, underprivileged group inauthentically lip-sync a story that is not their own.

In telling the story of a particular moment in Australian history, Down Under has aimed for the right thing by attempting to include the perspective of the Other. But, ultimately, it lacks punch, finesse and understanding. It assumes that Australians are ready to laugh at an issue of great sensitivity, thereby negating its responsibility to account for the political context within which the film is being released. Given the ongoing marginalisation of Arabic-speaking and Muslim groups as well as the rise of Islamophobia, it should be evident that the sentiments that fuelled the Cronulla Riots are not uncomfortable truths of the past to be looked on and laughed at from our current progressive state, but rather unfortunate realities that still exist today.

Endnotes

| 1 | See, for example, Nahid Afrose Kabir, ‘The Cronulla Riots: Muslims’ Place in the White Imaginary Spatiality’, Contemporary Islam, vol. 9, no. 3, September 2015, pp. 271–90; Scott Poynting, ‘What Caused the Cronulla Riot?’, Race & Class, vol. 48, no. 1, July 2006, pp. 85–92; and Scott Poynting, Paul Tabar & Greg Noble, ‘Looking for Respect: Lebanese Immigrant Young Men in Australia’, in Mike Donaldson et al. (eds), Migrant Men: Critical Studies of Masculinities and the Migration Experience, Routledge, New York & London, 2009, pp. 135–53. |

|---|---|

| 2 | See Ryan Barclay & Peter West, ‘Racism or Patriotism?: An Eyewitness Account of the Cronulla Demonstration of 11 December 2005’, People and Place, vol. 14, no. 1, 2006, pp. 75–85; and ‘Case Study Four: The Cronulla Riots – The Sequence of Events’, Reporting Diversity website, <http://www.reportingdiversity.org.au/cs_four.html>, accessed 1 November 2016. |

| 3 | ‘The Girls #2, Cronulla Beach’, Art Gallery of New South Wales website, <https://www.artgallery.nsw.gov.au/collection/works/398.2011/>, accessed 1 November 2016. |

| 4 | Louise Schwartzkoff, ‘Mateship up Against Tribal Mentality’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 29 April 2008, <http://www.smh.com.au/news/arts/mateship-up-against-tribal-mentality/2008/04/28/1209234762131.html>, accessed 1 November 2016. |

| 5 | See, for example, Luke Buckmaster, ‘Down Under Review – Gusty Black Comedy About Cronulla Riots Tackles Racism Head on’, The Guardian, 16 June 2016, <https://www.theguardian.com/film/2016/jun/16/down-under-review-gutsy-black-comedy-about-cronulla-riots-tackles-racism-head-on>, accessed 1 November 2016; and Paul Byrnes, ‘Down Under Review: Cronulla Riots Comedy a Daring, Welcome Blast of Fresh Air’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 11 August 2016, <http://www.smh.com.au/entertainment/movies/down-under-review-cronulla-riots-comedy-a-daring-foulmouthed-blast-of-fresh-air-20160810-gqp1oc.html>, accessed 1 November 2016. |

| 6 | For a contrasting perspective, see Amal Awad, ‘Down Under Review: Cronulla Riot Racism Comedy Swings, Misses’, SBS Movies, 7 August 2016, <http://www.sbs.com.au/movies/review/down-under-review-cronulla-riot-racism-comedy-swings-misses>, accessed 1 November 2016. |

| 7 | StudioCanal, Down Under press kit, 2016, p. 2. |

| 8 | Abe Forsythe, ‘Director’s Statement’, in ibid., p. 4. |