According to F Scott Fitzgerald there are no second acts in American lives, but filmmaker Stephan Elliott has demonstrated that there can be in Australian lives. After the enormous success of The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert (1994) he suffered more than a decade of severe personal and professional setbacks, which included two box office disasters and a near-fatal skiing accident. During the recovery process, throughout which he had to relearn how to walk, Elliott began the second act of his life by working on the highly successful stage musical version of Priscilla and his well-received 2008 adaption of Noël Coward’s play Easy Virtue.

Now, Elliott explains, he no longer feels he has anything to prove. With his sixth feature film, A Few Best Men (2012), he simply wanted to make something fun: ‘It’s a big silly piece of nonsense and if people laugh then I’m happy.’ But the more he talks about the cultural stereotypes that he undermines and exaggerates in A Few Best Men, the more there is a sense that beneath the silliness is a sly critique of the way Australians view themselves.

The story about a wedding that goes off the rails thanks to the behaviour of the best man and groomsmen was originally set in London before Elliott came on board and relocated the action to the Blue Mountains. The script by Dean Craig, who also wrote Death at a Funeral (directed by Frank Oz in 2007 and remade by Neil LaBute in 2010), had been doing the rounds in Hollywood for close to ten years. According to Elliott, Craig was initially devastated when he saw The Hangover (Todd Phillips, 2009), which charted similar terrain. But it turned out to be the catalyst for finally allowing A Few Best Men to get made, since The Hangover cemented the popularity of what Elliott sees as a new subgenre of wedding films:

Wedding films have been working for years for girls. There was an old rule in Hollywood that no wedding films can fail. But basically they were just for girls. Then when Wedding Crashers [David Dobkin, 2005] came along it suddenly invented this entire new genre, which is wedding movies for boys. So the girls could go because they could still get the wedding and the boys could go for the bad behaviour. It is a new genre that has only recently been born and it’s just right for the plucking.

Changing the location from England to Australia was something that Elliott had to fight for, but the end result is a film that is an inverse of ocker comedies such as The Adventures of Barry McKenzie (Bruce Beresford, 1972). In such films the English are typically portrayed as prim, refined and uptight while the ‘invading’ Australians are crude, loveable larrikins. In A Few Best Men it is the Australians who are proper and upper class while the English characters represent anarchy, disrupting social norms.

Elliott’s decision to give the English characters qualities usually associated with Australians is in part due to his experiences living in the UK:

Trust me – they’re yobs. I love the English dearly, but central London just turns into a shit fight Thursday, Friday and Saturday night. It’s a really yobbish culture. So I decided this time I was going to make a film about good-looking Australians with good manners and nice teeth, who have money – and we all know these people – and for the first time ever I was going to make the English the yobs. So it was quite a flip. I can’t wait to see how the film is going to go down in England.

I decided this time I was going to make a film about good-looking Australians with good manners and nice teeth, who have money – and we all know these people – and for the first time ever I was going to make the English the yobs.

– Stephan Elliott

Not only was Elliott keen to show a side of the English that better resonated with his own experiences, but also to advance the way Australians view themselves:

Enough of the cultural cringe. I think it’s time to grow up a bit. If you tried to make The Castle [Rob Sitch, 1997] now I think people would go, ‘Okay, enough already.’ It’s time to change. We’ve got to move on. The country is moving.

As further evidence of just how prevalent the stereotype of the boorish Australian is, Elliott describes how American test audiences were completely fascinated by his portrayal of the affluent Australian family in A Few Best Men:

The Americans didn’t realise that these types of Australians existed. The whole world is going down and meanwhile Australia has one of the strongest economies in the world. Guess what? We are actually sophisticated.

It is likely that UK audiences won’t respond too badly to the portrayal of the English characters as reckless buffoons. While such caricatures are unusual in Australian cinema they are common in England’s self-deprecating culture. Most interesting will be how Australians respond to seeing themselves in a film where they are mostly portrayed as uptight, materialistic conservatives obsessed with status and keeping up appearances; Elliott has previously ridiculed the way Australians perceive themselves and it didn’t go down well.

Elliott’s first film after the enormous success of Priscilla was Welcome to Woop Woop (1997). If A Few Best Men challenges the Australian cringe by completely rejecting it, Woop Woop challenges the cringe by pushing it to its most grotesque extremes. The film, about an American who is held captive by the deranged inhabitants of an Australian country town, is essentially a comedic version of Wake in Fright (Ted Kotcheff, 1971) with some of the nightmarish imagery of The Cars That Ate Paris (Peter Weir, 1974) thrown in. Perverse, ugly and savage in its parody of Australian values and culture, it has since been described as career suicide for Elliott.

Woop Woop’s timing was terrible – it was at the wrong place in history. When Pauline Hanson, who was in office at the time, announced that she liked it, I realised that the joke had gone terribly wrong.

– Stephan Elliott

The problems with Woop Woop were numerous and mostly out of Elliott’s control. It was taken off him by the studio and recut so that a lot of the really harsh commentary was removed, resulting in a confused and diluted film. It was also released at a time when Australians were simply not ready for what it had to say about them:

Priscilla’s timing was brilliant – it was exactly the right point in time. Woop Woop’s timing was terrible – it was at the wrong place in history. When Pauline Hanson, who was in office at the time, announced that she liked it, I realised that the joke had gone terribly wrong. I mean, the joke was Pauline Hanson. I was going for the jugular, saying ‘This has got to end.’

Elliott now considers Woop Woop an unfinished project that he still intends to return to. In the meantime, exaggerating cultural clichés to the point of absurdity is one aspect of Woop Woop that Elliott has extended to A Few Best Men. Most striking is the establishing shot of Sydney in A Few Best Men where a blood-splattered surfboard with a big shark bite taken out of it can be seen floating in the harbour. It makes sense that when asked, Elliott lists filmmakers such as Jacques Tati and Blake Edwards as his influences, since in their own ways they also used physical comedy and cultural stereotypes for the purposes of satire and social commentary. But Elliott’s greatest influence is an Australian performer who appeared in many of the original ocker comedies that A Few Best Men playfully undermines.

The biggest comic influence I’ve ever had is Barry Humphries [who appears in Woop Woop]. I’ve met President Clinton and I wasn’t nervous at all. I meet Barry Humphries and I get nervous, because I realise how much of an effect he had on me as a kid. He pioneered a style of humour. We’re watching it die off now because people don’t want to know about it, but it’s still very funny.

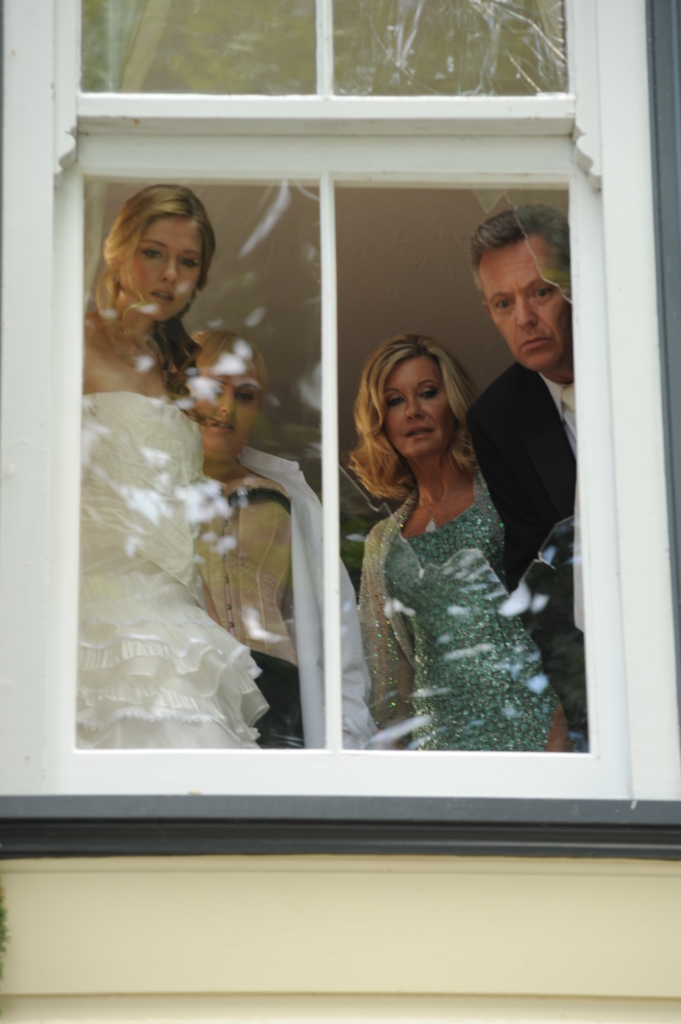

Elliot speaks affectionately about the Best Men cast and is especially fond of Olivia Newton-John, whom he has known for years. Newton-John plays the mother of the bride who finally lets loose during the wedding. ‘She’s an uptight wife who’s got a miserable life married to a miserable husband and she just goes mad,’ says Elliot. ‘We’ve all been to this wedding. Every one of us has been to this wedding.’

Another important role in the film is that of the best man, which is played by Kris Marshall, the English performer who appeared in Love Actually (Richard Curtis, 2003) as the young man who travels to the US to pick up women. Elliott and Marshall have a striking resemblance so for years after Love Actually came out people would ask Elliott for his autograph: ‘I got so sick of being told “I loved you in Love Actually”.’ When Elliott ran out of time to make his on-camera debut as the butler in Easy Virtue, he figured he would do the next best thing and offer the part to Marshall. As it turned out, not only do Elliott and Marshall look alike, but they are ‘terrifyingly, frighteningly similar’. The only direction from Elliott that Marshall required was, ‘Just play me.’ So far it has only been two films that the pair have worked on together, but there is the potential for them to forge a productive director–actor relationship.

The other reason that Elliott was unable to play the role of the butler in Easy Virtue was because he was still on crutches – still learning to walk after breaking his back, pelvis and legs in his 2004 skiing accident. ‘Learning to walk again – you see it in movies, but trust me, it’s really scary,’ he says. ‘It takes longer than a learning-to-walk montage.’ Not that Elliott blames the lull in his career exclusively on the accident. After the poorly received Woop Woop came Eye of the Beholder in 1999, a thriller starring Ewan McGregor and Ashley Judd that was also a critical and commercial failure. ‘Eye of the Beholder knocked me around so badly. I dropped the ball after that one,’ admits Elliott. ‘I lost my house, I lost the shirt off my back and I lost my confidence. So I was out there lost for a while.’

After the accident Elliott was told he was going to die and when that didn’t happen he was told he was never going to walk again. Elliott proved doctors wrong on both counts, leading to a new surge of confidence that allowed him to start making films again.

I had a life-changing moment where I was told I was going to die. I go back to that every now and then when things are getting too stressful and too weird. I have a grounding moment and I can go back and say, ‘You know what? You can do anything. And who cares?’ I can get yelled at now – and you do get yelled at as a director. I get yelled at all the time. I just sit there and smile. It doesn’t hurt anymore. It’s quite liberating! ‘Keep screaming, tell me when you’re finished.’ I’m not frightened anymore. That’s the most interesting thing that’s come out of it. I’m actually not frightened of anything – except Barry Humphries.

After all that has happened to Elliott since making his feature film debut Frauds in 1993 (starring Hugo Weaving, Josephine Byrnes and singer Phil Collins), how does he feel about still being referred to as the writer and director of The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert?

It bugged me for about a decade – really bugged me and drove me mad. The other thing about it is that I never made any money out of it. I was a kid, I signed a napkin. I got paid a flat fee and the film went on to make hundreds of millions of dollars. So that didn’t help either. And then I was just known as the Priscilla guy.

Elliott learned to embrace his legacy after receiving some blunt advice from Richard O’Brien, the actor and writer forever known for creating the cult musical The Rocky Horror Show, and co-writing and acting in the film adaptation The Rocky Horror Picture Show (Jim Sharman, 1975).

Richard O’Brien slapped me across the face and said, ‘Steph – how many people, even the most famous directors in the world, have got a Priscilla? It’s a gift. It’s not a ball and chain, it’s a gift. Maybe it’s all you’ll be remembered for, but you know, half your luck!’ That stuck with me for a bit. By the time we put Priscilla on stage, I had learned to love the old bird again. And now she just is what she is and she’s great. Yes, I will always be the Priscilla guy and I’ll never be able to live up to it. Since the accident I’m not even going to try.

Elliott is embracing this second act of his life. He sounds like he had the time of his life making A Few Best Men – but when you get him talking about its underlying social critique, not to mention his passion for one day completing Welcome to Woop Woop in the way it was supposed to be, there is the distinct suggestion that behind the joviality is a fiery cultural commentator. Of course, nothing is ever perfect, and even having made peace with his legacy as the Priscilla guy comes with a downside: ‘Whenever I hear the first bars of “I Will Survive” I want to throw up.’