Described as a psychosexual thriller, Jane Campion’s In the Cut (2003) explores the intense sexual relationship between a creative writing teacher and a detective, set against the backdrop of a serial killer investigation in New York City.

The teacher, Frannie Avery (Meg Ryan), is a student of words, particularly slang, and her fascination with subway poetry betrays an insatiable curiosity that leads her into dangerous situations, including a relationship with a man she suspects is the killer. This connection between sex and death seems only to fuel her curiosity and her desire to take greater risks. In the Cut explores the darker side of romance and the particular dangers that the myths of romantic love pose for women.

Adapted from Susanna Moore’s 1995 novel of the same name, In the Cut is not your typical Meg Ryan film. This heroine is introverted and lives in the shadows; she is cool and reserved with rarely a smile, let alone the trademark perkiness we have come to associate with the Ryan persona. The muted brown tones of her hair and wardrobe assist in this transformation of sunny, blonde Americana into repressed sexual desire. While Ryan has previously taken detours from her star persona in dramatic roles such as the alcoholic wife in When a Man Loves a Woman (Luis Mandoki, 1994) and a stripper in Hurlyburly (Anthony Drazan, 1998), rarely has an on-screen image been so effaced as it is here, in Ryan’s incarnation of Frannie.

In the Cut is also not a typical genre film. The serial killer mystery plot is merely the skeleton upon which Campion hangs the clothing of desire, and this is the stuff from which she weaves a compelling, disturbing film. The ‘whodunit’ aspect seems almost irrelevant to the film’s primary purpose; indeed, the final revelation of the killer’s identity seems to be merely tying up loose ends, rather than providing a satisfying conclusion to the mystery. What is important, however, is the centrality of the whodunit question to Frannie’s desire, as lust and paranoia become intertwined.

As an exploration of female masochism, then, In the Cut is a typical Jane Campion film. Like Isabel Archer (Nicole Kidman) in The Portrait of a Lady (1996) or Ada (Holly Hunter) in The Piano (1993), Frannie is a woman who seems to desire her own subjugation at the hands of a powerful male. Yet as she did in these previous films, Campion is able to explore the disturbing nature of her heroine’s desires, while at the same time affirming the independent nature of this woman and the role of choice in her pursuit of the dark side of desire. It is clear that Frannie has chosen her own dark path, even though she may not know where it leads. Frannie’s path is signposted by her repeated encounters with quotations of poetry on subway posters, including a timely commentary from Dante: ‘for I had wandered off from the straight path’. Significantly, Campion has changed the ending of Moore’s novel, from one that was punitive and pessimistic, to one of survival. This change points to Campion’s own positive view of women’s sexual self-determination. She has described her alternative ending as ‘redemptive’ and I think this points to the optimism that is at the heart of Campion’s breed of feminism.[1]Jane Campion, radio interview, The Conversation Hour with Jon Faine and Jill Singer, 11am, 774 ABC Melbourne, 10 November 2003.

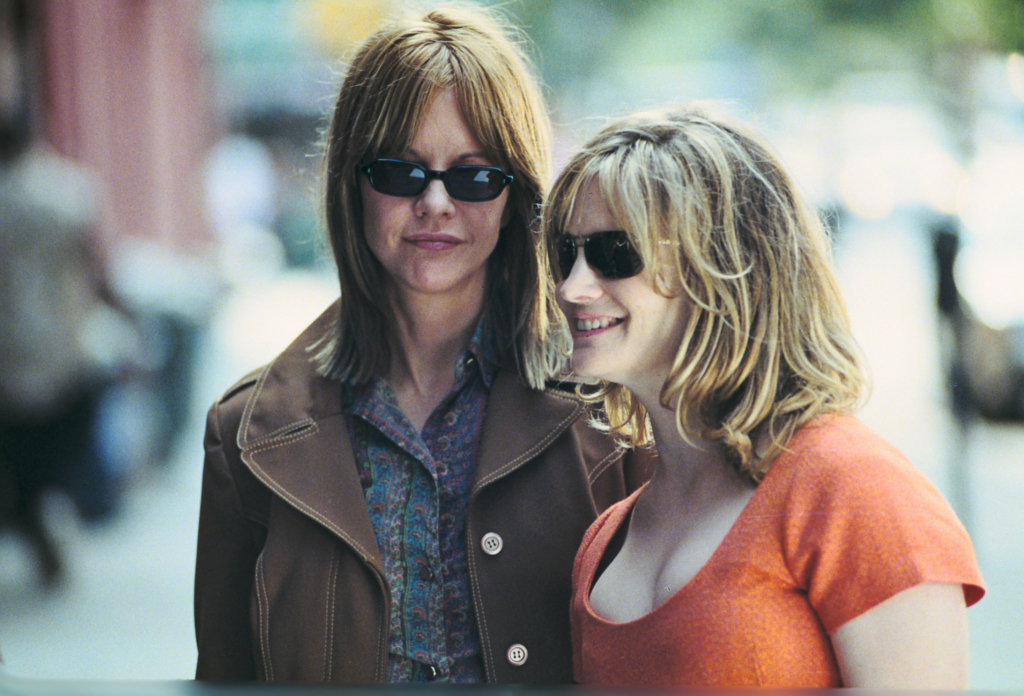

In the midst of such a dark, disturbing film, where the threat of violence against women seems constant, it is surprising to find such scenes of warmth and humour as the interactions between Frannie and her half-sister Pauline (Jennifer Jason Leigh). One of Campion’s trademarks is her insightful portrayal of sibling relationships, whether dysfunctional, as in Peel (1982) and Sweetie (1989), or affectionate, as in An Angel at My Table (1990). The physical intimacy and emotional connection between Frannie and Pauline recalls the close bond between Ada and her daughter Flora (Anna Paquin) in The Piano. The scenes between Ryan and Leigh provide sensuous respite from the threat of violence on the streets outside. As the girls chat and giggle about sex and clothes, the camera lingers on the surface of their skin, the curves of the female stomach, the feather-like touch of fingers. It is also in these scenes that Campion has the opportunity to explore further the myths of romantic love and the traps they lead women into. Unlike Frannie, Pauline throws herself headlong into amorous pursuits, to the point where she is taken advantage of and then discarded, and yet she still wants more. Despite the sisters’ ability to laugh at Pauline’s infatuation with a married doctor, there is also a melancholy tone that suggests their unspoken awareness that she has fallen victim to the promise of romantic love; as Pauline moans, ‘I just want a husband, is that too much to ask?’. In one scene, Frannie relates to Pauline the story of how her mother met their father, and then how ‘he killed her’ when he left – she died of grief. When Frannie imagines her parents’ courtship, Campion inserts sepia-toned period footage that recalls her surreal black and white travelogue in Portrait or the animated sequence that accompanies Flora’s vivid storytelling in The Piano. As Frannie journeys further into darkness, this fairytale scene is repeated with shocking images of violence against Frannie’s mother by the man she loves. The threat of violence in the courtship contract is made explicit in the modus operandi of the serial killer, who leaves a diamond engagement ring as his signature on each of the victims’ left index finger.

Like her portrayal of the intimate relationship between Frannie and Pauline, Campion is equally skilled at evoking the homosocial space of the detective squad, in the macho posturing of Detective Malloy (Mark Ruffalo) and his partner Rodriguez (Nick Damici). Each time Malloy is chatting up Frannie, Rodriguez interrupts and re-establishes his own bond with Malloy, most amusingly with a water pistol. Campion consistently finds the humour in these self-conscious assertions of masculinity. Kevin Bacon’s uncredited turn as a jilted boyfriend-turned-stalker also elicits laughter, albeit of the nervous variety, until his lovesick posturing takes on a tone of menace and imbalance that suggests, at least to the audience if not to Frannie, that he may be the serial killer. Alongside his recent powerful yet restrained performance in Clint Eastwood’s Mystic River (2003), it seems that Bacon, like Ryan, is continuing to evolve as an actor midway through his career as a ‘star’. Completing the circle of male characters (and potential suspects) is Frannie’s student Cornelius Webb (Sharieff Pugh), an African-American whose attempts at courtship seem, at least initially, to challenge stereotypes of interracial romance in film. Ultimately, however, these stereotypes are reinforced when Frannie rejects him after a drunken pass and he becomes violent and angry.

The film’s palette is dominated by brown and sepia tones, conveying a sense of New York’s grimy summer atmosphere. In what might be termed ‘film brun’, Campion and her Australian DOP, Dion Beebe, have created a daytime equivalent of the claustrophobic shadows associated with the nightscapes of film noir. Campion and Beebe also constantly play with focus within the hand-held frame, as objects and faces fade in and out of view, mirroring Frannie’s clouded vision and her dream-like state. The sex scenes between Ryan and Ruffalo are quite explicit but sensuously photographed and accompanied by a score that plots the rise and fall of Frannie’s passion. It is in bed that Frannie and Malloy have their most intimate and revealing conversations, and these are the moments where we see the extent to which Malloy has broken through Frannie’s cool detachment. After they first make love, she already seems a changed person, smiling and talking in a way that suggests she is beginning to open up. With openness comes vulnerability, however, and just as she begins to trust Malloy, Frannie becomes convinced he is lying to her. Thus the seeds of her paranoia and fear are sown.

In a recent interview, Campion observed that ‘all my best films have had a very divisive reaction, beginning with Sweetie. And I think that they’re strong and that people, if they don’t like them, they don’t [just] not like them, they really hate them! And if they love them, they’re really passionate about them’.[2]Campion, interview with Margaret Pomeranz, The Movie Show, SBS, 12 November 2003. The critical reaction thus far to In the Cut follows this pattern, with a range of responses from enthusiastic praise for Campion’s vision and her actors’ performances to harsh criticism, mainly directed at the execution of the thriller plot.[3]For example, both Pomeranz and David Stratton gave the film five stars (The Movie Show, SBS, 12 November 2003) and Mick LaSalle described it as ‘a near-great achievement’ (San Francisco Chronicle, 31 October 2003). In contrast, the UK press was generally dismissive of the film: see, for example, reviews by Peter Bradshaw in The Guardian, 31 October 2003, and Philip French in The Observer, 2 November 2003. The division is illustrated by the New York Daily News, which ran separate and opposing reviews by its two lead film critics on the same day.[4]New York Daily News, 22 October 2003. Jack Mathews and Jamie Bernard give negative and positive reviews respectively. Mathews writes ‘I hate the movie’, describing it as ‘banal Jack-the-Ripper melodrama’ and ‘Pure pulp … almost unbearably pretentious’. In contrast Bernard declares, ‘I love this movie’, and adds that ‘very few movies have evoked this kind of sexual longing mixed with dread and insecurity – especially from a female point of view’. This mixed reception confirms Campion as a film-maker who continues to challenge the audience and to push the boundaries of film-making; in this case, genre film-making. Some will view Campion’s engagement with genre as less than satisfactory, as her film fails to follow the basic conventions before overturning them. But this reading of the film is based on Campion’s treatment of genre solely in terms of plotting. In terms of getting at the heart of the genre’s thematic – namely fear of violence and death – Campion’s reworking of the detective/noir genre is more successful:

What I found really interesting about working in the noir framework was exploring fear and I think what’s great about noir and genre and detective genre films – what I found really liberating – was a way of being scary and frightening and investigating fear itself. That’s something we all live with – fear is very strong for us – but it’s in a framework that’s acceptable, a story like ours is supposed to be dark, it’s a place where you work that stuff out.[5]Campion, The Conversation Hour.

In the Cut is a film about passion and hatred which, in turn, like Campion’s earlier work, inspires passion and hatred. It confirms Campion’s reputation as one of the most debated auteurs of the last decade and while her work may not be seen on our screens again for some time,[6]Campion recently announced she is taking a four-year break from film-making, to spend more time with family and friends: ‘I just want more time without a schedule, I want time for me and my friends. I love film-making and not including film school, which was the most frantic of it all, I’ve had about twenty years in the industry, always preparing for something or finishing something else, and I’ve loved it but it’s so obsessive. I’ve had great friendships and maybe I will come back to it if anyone ever wants me to make a film again’ (The Conversation Hour). she will remain a key figure in future discussions of women and film, both in front of and behind the camera.

Endnotes

| 1 | Jane Campion, radio interview, The Conversation Hour with Jon Faine and Jill Singer, 11am, 774 ABC Melbourne, 10 November 2003. |

|---|---|

| 2 | Campion, interview with Margaret Pomeranz, The Movie Show, SBS, 12 November 2003. |

| 3 | For example, both Pomeranz and David Stratton gave the film five stars (The Movie Show, SBS, 12 November 2003) and Mick LaSalle described it as ‘a near-great achievement’ (San Francisco Chronicle, 31 October 2003). In contrast, the UK press was generally dismissive of the film: see, for example, reviews by Peter Bradshaw in The Guardian, 31 October 2003, and Philip French in The Observer, 2 November 2003. |

| 4 | New York Daily News, 22 October 2003. Jack Mathews and Jamie Bernard give negative and positive reviews respectively. Mathews writes ‘I hate the movie’, describing it as ‘banal Jack-the-Ripper melodrama’ and ‘Pure pulp … almost unbearably pretentious’. In contrast Bernard declares, ‘I love this movie’, and adds that ‘very few movies have evoked this kind of sexual longing mixed with dread and insecurity – especially from a female point of view’. |

| 5 | Campion, The Conversation Hour. |

| 6 | Campion recently announced she is taking a four-year break from film-making, to spend more time with family and friends: ‘I just want more time without a schedule, I want time for me and my friends. I love film-making and not including film school, which was the most frantic of it all, I’ve had about twenty years in the industry, always preparing for something or finishing something else, and I’ve loved it but it’s so obsessive. I’ve had great friendships and maybe I will come back to it if anyone ever wants me to make a film again’ (The Conversation Hour). |