A while ago, a group of friends and I stayed up all night at a farm. At first, we were just hanging out in the farmhouse, listening to music, talking. Later, we walked up a nearby hill, topped with a copse of trees. That night everything seemed imbued with some profound meaning, somehow deeper than itself: the trees spectral and almost sentient, the pond at the bottom of the hill seemed altogether larger, its banks not dry and dusty. The darkness threatened to unveil shadowy forms at any moment.

The sense of immanence (as philosophers would call it) that I felt that night has stayed with me since then, and it is something I think of as particularly related to night-time, when things seem somehow ‘other’. In the morning the sun rose, the high stratus clouds pink and windswept, everything suddenly clear and cold and alive. The world was altogether changed. In fact, it seemed to be another world, a brilliant replica superimposed upon the night-time one. We sat in a field, the night having passed us by, and one of my friends said, ‘It’s sad that we don’t get to experience watching the sunrise more often.’

Shimmering surfaces

The documentary Night (Lawrence Johnston, 2007) attempts to cover just this sort of philosophical and emotional terrain. Opening with spectacular images of a storm and sunset, Night promises much. The opening reflections from Ross Gibson are:

Well, a sunset for me is a – it’s a wonder – and what I love about it is the way that it exists because of that basic condition of darkness coming back, light and dark are constantly surprising each other, I think. It’s like they vie with each other for twenty minutes … or so, and we just stand around and look at that negotiation.

‘Well, a sunset for me is a – it’s a wonder – and what I love about it is the way that it exists because of that basic condition of darkness coming back, light and dark are constantly surprising each other.’

– Ross Gibson

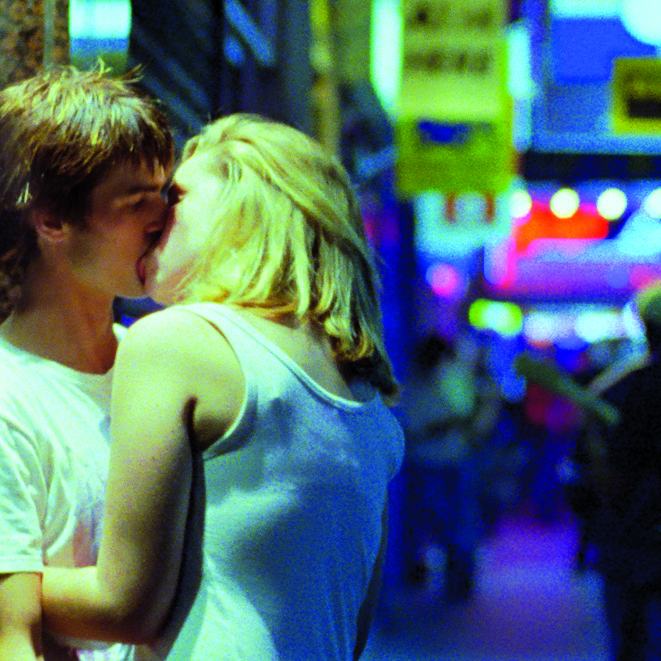

What emerges over the following hour and a half is a series of reflections by people (including Christos Tsiolkas, Avril Carruthers, Bill Henson, Jane Guy, Declan Kelly, Neneh Owen-Pozzan, Jarnie Blakkarly, Paul Capsis, Justin Strunk, Dai Le, Robert Herbert, Phil James, Emma Magenta, George Gittoes, Polly Staniford, Phil James, Ross Tognolini, Louis Kennedy and Geoff Barron) on the meaning of night, accompanied by images. This is not a bad combination. The best of the images evoke feelings within us: we see (and one of the interviewees notes) how people become more intimate at night. We see lovers kiss, partners hold hands. We see the rituals of dress and fashion: groups of young women with heels and clothes, men with stylish or style-less open-collared shirts. We see that night is a particularly social time. And yet it is also a particularly anti-social time. Most murders, we discover, happen at night. In all of this, there are arresting and beautiful images. In its best moments, Night provokes us to see the world anew. These moments are somewhat akin to sitting at a window at night, and watching the world pass by. It is a rare experience: usually, we have somewhere to go, people to meet, something to do. The chance to simply sit and watch allows time and space for reflection, to really notice the details: the light, the body language of people, their clothes, the sounds of cars and the wind.

But although thought-provoking, Night wants to delve beneath the surfaces into the meaning of all these things. Its technique for doing so is its interviewees, who discuss what night means to them. They talk about drinking too much alcohol, experiencing night as children, driving taxis. The relation between the images and the commentary is not direct; rather, the interviews parallel the images. There is, it must be said, a paucity of depth to these comments. As Adam Elliot describes:

I think after four or five drinks I feel fabulous. Trouble is I want that feeling to continue so I’m someone who likes to stay out till the bitter end, till it’s daylight, and then spend the next twelve hours having anxiety attacks and bouts of depression because the night’s brought too many pleasures.

In its best moments, Night provokes us to see the world anew. These moments are somewhat akin to sitting at a window at night, and watching the world pass by.

It’s not that there is nothing to relate to here, simply that this moment comes and goes without much investigation. There is no indication why, short of relating it to our own experience, this should have much significance. The film doesn’t help this by giving no indication of who these people are. It’s as if the filmmakers simply asked their friends on the spur of the moment.

Of course, one of the hazards of philosophy is its tendency to tread the line between profundity and banality. More specifically, pop philosophy dictums such as existential or Zen notions of being (‘you are what you do … man’) or postmodern subjectivity (‘create your own reality … man’) threaten to dissolve into philosophy’s equivalent of fast food: it looks like food, the pictures make it look like food, but you’re filled with a decidedly empty feeling when you’ve finished it. The point is that in Night the aphoristic reflections of the interviewees tread just this line. If you sit down and really think about their comments, they do, in fact, merit attention. The problem is that it is the job of the documentary to lead us deeper into these questions, to help us think them through, to show us possible answers. Instead it skates over them as if they were self-evident, as if they were simply a flat surface. One of the most interesting moments in the film, for example, is when Phil James notes that in the early days of the colony, Sydney would have been shrouded in darkness at night. Night was not, therefore, a time of work. It would also have been a time of danger:

Electricity was founded with the mission to roll back the darkness, roll back the night and – and bring civilization to the colony. Most activity then would’ve only been able to have been conducted during daylight hours. At night people would’ve gone back into safety, into their homes or wherever they were living and very little activity would’ve been conducted at night. I imagine that the streets of the colony in those days were quite dangerous places. Light would’ve made the streets safer and for people to – to use them and – and as a result of that more people would have travelled at night, used the streets, visited each other and the like.

Suddenly we are asked to imagine a world before electric lighting, where in winter at 6pm, for example, you would be at home and would not go out. The rhythms of life – of the body itself – have changed, says one commentator. But this moment is over too soon, without much investigation, and we are back to shots of cars passing along city streets.

Suddenly we are asked to imagine a world before electric lighting, where in winter at 6pm, for example, you would be at home and would not go out. The rhythms of life – of the body itself – have changed, says one commentator.

If Night could be described as a montage sequence with accompanying reflections, it also suffers from a lack of structure. What is the organizational principle of the documentary? As far as I can see, there is none. There are many that could have been used. The film might have been divided into different aspects of the night: early night, mid-night, early morning. It might have traced the shifts that occur over this period. Alternately, it might have investigated the ways in which modern and pre-modern societies experienced and viewed the night. Had this been the case, it might have been an argument about modern society (here I’m thinking of an argument like that put in Marshall Berman’s wonderful book All That is Solid Melts into Air: The Experience of Modernity), in which he describes the transformation of modern Paris (and in another chapter, the construction of St Petersburg) by modern society.

Finding a way

Night suffers, in other words, from a lack of argument. A film – any film – must have something to say. I’m not here being instrumentalist, suggesting that this is all that a film needs, but it is a precondition for a good one. And it is definitely a precondition for a compelling documentary. Unfortunately, we leave Night without any sense of the filmmakers’ vision. The film is impressionistic.

But even then, even without an effective structure, Night limits itself unnecessarily in its subject matter. The concept of a documentary on night-time is a great one. There are so many rich possibilities that could be covered. You could explore the myths of day and night of different civilizations, showing how such myths embody meanings about what it means to be alive, and everyday life in those times. The most powerful god in Egyptian mythology is Ra, the sun god. This is not by accident, for the sun was crucially important to the growing of the crops that were critical to the survival of such agricultural societies. The Vikings, on the other hand, have the following myth:

Two riders named Day and Night were charged with guiding the sun and moon on their daily journey across the sky. They were pursued by a wolf intent on devouring them and from time to time, it did catch them in his mouth. Because of the cries of the terrified people of Midgard, the wolf released them, only to pursue them once again.[1]See Jim Cornish, The Viking Creation Myth, <http://www.stemnet.nf.ca/CITE/v_creation.htm>, accessed 1 December 2007.

Such myths are replete with narrative and metaphorical resonances. Investigations into historical notions of night and day might then give way to an exploration of contemporary ideas and the transformation of these ‘myths’ under the pressure of industrial society. There are, for example, the enduring terrors of the night, descendents from medieval ignorance, such as the vampire (which cannot survive the sunlight), which have now become resonant myths of modernity in works such as Richard Matheson’s wonderful novel I Am Legend (to be released shortly as a film and also filmed as The Omega Man [Boris Sagal, 1971]). The novel tells the story of Robert Neville, the last person alive in a world of vampires. Neville is surrounded in his house, only able to go out during the day. He spends his time recalling the painful past, the death of his wife and daughter; drinking; killing vampires during the day as they sleep; and trying to find the scientific basis to the effectiveness of garlic, wooden stakes and light in killing vampires. What Matheson touches is all the unbridled alienation and fear of suburbia. Not only are the neat little houses and the cars and lawns a profoundly lonely and isolating experience, but Matheson takes us to the logical end point: not only do we feel distance from our neighbours, but they are in fact horrifying night-creatures seeking to suck our blood.

Perhaps this takes us too far from the subject of the night, and yet it seems to me to be suggestive in the way that Night is not. The score is not enough to invest the admittedly beautiful imagery with the depth it searches for. Night, then, must be considered a film of missed opportunities.

If you are happy to sit back and let the images roll over you, and listen to the grandiose soundtrack; if you have a restless imagination and are able to generate from the images your own thoughts about the meaning of night (and this was my personal experience); then the film will be enjoyable. But in terms of offering us the filmmaker’s vision of the world, in terms of providing us with a new picture of the meaning of day and night, sadly, Night leaves us in the darkness.

Endnotes

| 1 | See Jim Cornish, The Viking Creation Myth, <http://www.stemnet.nf.ca/CITE/v_creation.htm>, accessed 1 December 2007. |

|---|