It’s 2014. I’ve been conducting interviews for Metro for over ten years. A last-minute reassignment sees me handling the new Spierig Brothers thriller, Predestination. This is good news. I loved their first feature, Undead (2003), and although their sophomore effort Daybreakers (2009) had its flaws, it certainly didn’t lack ambition. If they’ve managed to adapt Robert A Heinlein’s 1959 short story ‘—All You Zombies—’ successfully, then Predestination could be a corker. I sit down to watch the film with my wife. She’s got no idea what it’s about, so I’m determined not to give anything away.

*

It’s 2003. I’m heading in to my first interview for a magazine called Metro. I’ve never done an interview before, and frankly I’m a little worried. I’m talking to the directors of Undead, two brothers by the name of Peter and Michael Spierig. They’d seemed like perfectly nice guys at the screening, but the thing nagging at me is that they’re identical twins. Put simply: when I’m transcribing their voices later on, how am I going to be able to tell which is Peter and which is Michael?

As it turns out, the answer is simple. Clearly, the brothers have done this before, and ask whether I’d like them to say their names before each comment. Relieved, I respond that that would be marvellous. We have a great chat, and my maiden interview is completed with no hassles whatsoever.

*

It’s 1992. I’m seventeen years old and I’m reading Robert A Heinlein’s ‘—All You Zombies—’. The story isn’t very long, but it completely blows my head apart. I’ve read time-travel stories before, but never one quite as ruthlessly transgressive and imaginative as this. It involves two men, the Unmarried Mother and the barman, conversing in a bar, the former telling the latter ‘the best story ever told’. He begins by saying, ‘When I was a little girl,’ and we flash back through his life as a woman, revealing her upbringing in an orphanage, her whirlwind romance with an older man and her subsequent pregnancy. However, after she gives birth, the doctors inform her that she’s actually in possession of male and female sex organs, and that complications during surgery have necessitated a sex change.

Then the time-travelling starts and things get really weird.

*

It’s 2014. I’m sitting down for my second interview with the Spierig Brothers, and they look exactly the same as they did in 2003. Predestination has just had its Australian premiere at the Melbourne International Film Festival (MIFF), and it’s clear to me that the film is by directors who have matured. Undead was the work of young men with something to prove – all flashy cameras and cartoon characters. Daybreakers was the transition piece, a hugely ambitious film that attempted to build an original world with the aid of Hollywood money, but never quite pulling it off. Predestination, for all its genre trappings, is a departure from the Spierigs’ earlier films in that it not only resolutely features three-dimensional characters, but is also the first time the directors have ventured into adaptation. I begin by asking why they did that.

‘There’s something wonderful about adapting another person’s work,’ says Peter,

because it changes your voice as a writer. And that was the thing we learnt doing this: that Heinlein’s voice is all through the film. It’s interesting because you feel like there’s another person involved as you’re writing. You lay his words out, and then you try to write in his style of language.

The interesting thing for me is just how much of Heinlein the brothers have taken. The author is one of the giants of science fiction, but surprisingly little of his work has been adapted for film – and certainly nothing as faithful as this. Indeed, during the first half of Predestination, part of me wondered whether the brothers had erred by remaining faithful to the source text in that much of their film is simply one person telling another a story. In a world where screenplay gurus remorselessly screech ‘Show, don’t tell’, the Spierigs have elected to do the opposite, and I wasn’t sure whether I could trust my own reaction to their choices. This is partly because ‘—All You Zombies—’ made such an early impression on me. Unfortunately for the Spierigs, I still remembered exactly where all the rabbits were hidden in Predestination’s magic show, and I therefore couldn’t be quite as impressed the second time around. That said, even as the familiar story unfolded, I was struck by both the strength of the acting and the directors’ bravery in simply allowing conversation to carry so much screen time.

Predestination, for all its genre trappings, is a departure from the Spierigs’ earlier films in that it not only resolutely features three-dimensional characters, but is also the first time the directors have ventured into adaptation.

I tell the Spierigs that, to me, Predestination feels like a film with two halves, the first of which is extremely talky. Exposition is often deathly – I recently switched off the pilot of Extant when a doctor clumsily informed her patient about information both of them already knew – and I ask whether it was difficult writing something with so much set-up. Michael answers that a lot of people had told them not to structure their script like that.

They kept saying, ‘Your first act is fifty minutes long,’ and it’s absolutely not […] but people assume it is. I love that idea. I think it’s a bold idea to tell so much of somebody’s story in the bar – particularly when the film starts and you’re assuming it’s going one way, and you get to the bar and you go, ‘What is happening now? Where did that other story go?’ […] I love watching films where I have no idea where it’s going to go. What is this all about, and how does this all intertwine?

Personally, I don’t mind the poke in the eye to the structure police, and I agree that Predestination scores because of both its unconventional characters and its unusual story. But, personal opinion aside, did the Spierigs struggle with writing that expository section?

‘I think, in this case, it’s so ingrained in the short story, the nature of this person telling a story,’ Peter explains.

I love the idea that this person says, ‘I’ve got the best story you’ve ever heard,’ and so they’re telling that story to win a prize. It’s not just ‘I am a doctor and this is what I do’; it’s storytelling. It’s the character saying, ‘Listen to my story.’ So I think, in that sense, the expositional element works, and I also think the movie has so many complex ideas that certain things need to be laid out – like, ‘This is my character. This is who I am. This is my life. I was a little girl when this happened’ – because there’s so much complex stuff coming. But, I don’t know, I love a lot of [Martin] Scorsese stuff with tremendous amounts of voiceover and it works brilliantly. It just depends. If the audience is engaged in the story, [and] they want to hear that story being told, then it’s fine.

*

It’s 2014, one week after the interview is complete. I’m re-reading ‘—All You Zombies—’ to see how it holds up. It’s still a seminal piece of work, but it’s marred by a flaw common to much science fiction of its age: it’s all ideas and very little heart. The mechanics of the story are simply that: we’re not invited to dwell on how the Unmarried Mother’s romance with her older, male counterpart actually occurred, thereby dodging its implausibility, and the ultimate motivations of the narrating barman are left murky. There is a final soliloquy that hints at pathos, but on the printed page it feels gnomic, as though Heinlein has approached something emotional and then recoiled into mystery, terrified he might reveal too much.

*

It’s 2014. I’ve finished watching Predestination with my wife. I’m finding it hard to make up my mind about the film. Certainly, the Spierigs circumvent a lot of the short story’s problems, partly through necessity. ‘—All You Zombies—’ is far too brief to sustain feature length, and so the film’s second half expands on the notion of a time-travel agency, thereby forging into new territory that I can’t predict. Perhaps oddly, given the subject matter, it feels more traditionally written. There’s a romance (albeit the supremely unusual one that Heinlein refuses to illustrate); there’s thriller-type stuff involving the hunt for a bomber, and plenty of time-travel twists. Two days later, I ask the brothers whether that second half of the film was easier to craft.

‘No, I think the second half was harder,’ says Michael, ‘because so much of that bar stuff had already been laid out for us.’

Heinlein had done a very good blueprint for that. Obviously, how everything starts to intertwine, he [already] wrote, but adding in a whole other layer […] that whole scene in the university [in which the male Unmarried Mother meets and falls in love with his younger, female self, both played by Sarah Snook], there was nothing really written there. They meet, and that’s about it in the short story. So […] you assess what you think Heinlein wanted to get out of the scene, which is obviously [that] people fall in love. Okay, you fall in love with yourself – that’s a really hard thing to try to write.

After this admission, the Spierigs laugh – but they also confess to being terrified when it came to actually shooting the date scenes. The good news is that these are the most satisfying sections of Predestination, partly because they’re so sweet, but also because you can appreciate the degree of difficulty it took to execute them. After all, a literary creation can exist perfectly credibly in our own imaginations. We can imagine scenarios in which the Unmarried Mother romanced his female self and only realised in retrospect what had occurred. Predestination, however, asks the audience to believe in an actor playing both roles. We can see Snook rather than simply imagining the perfect version of her character/s, and, if her performance/s or the special effects make-up fails, then the whole scenario becomes a bad joke.

‘Until [Snook] came on board, we really had no idea whether it was going to work. And she handled it with such a delicate, intelligent, well-researched approach,’ says Michael. ‘I mean, one of her friends was going through the change – female to male – and she spent a lot of time with that person researching.’

‘But talking more about identity and things like that – who that person is,’ Peter clarifies. ‘Not so much the physical, but the mental, the social aspects of that.’

*

It’s 2003. Michael welcomes the audience to the MIFF screening of Undead, introducing it as a ‘piece of truly independent Australian cinema’. A couple of days later, I begin my conversation with them by asking what that statement meant.

‘When I said “truly independent Australian cinema”,’ Michael clarifies, ‘I mean [that] our film was financed entirely without any sort of government assistance whatsoever.’

‘Or studios, or anything like that,’ adds Peter. ‘Basically, we pulled the money directly out of our own pockets.’

I enquire whether they tried to get any film-funding assistance; they chorus ‘no’ in almost perfect unison. Could the lack of local horror movies be attributed to an elitist bent in the funding bodies?[1]The Spierigs’ 2003 responses that follow were first published in Dave Hoskin, ‘The Sharing of One Brain: A Conversation with the Spierig Brothers’, Metro, no. 138, 2003, p. 24.

‘We personally have been told from government funding bodies that we shouldn’t be making genre pictures,’ reveals Michael. ‘That they’re best left to the Americans … which doesn’t make sense to me, because the Japanese make some pretty damn good genre pictures.’

‘And the Europeans,’ laughs Peter.

‘I don’t know why we don’t make genre pictures,’ Michael continues. ‘There’s a huge market out there for it, and genre pictures are a lot easier to sell overseas than pretty much any other type of movie if you don’t have major stars.’

*

It’s 2014. The conversation is winding down. I can’t help reminding Peter and Michael about the statements of their younger selves, and I ask them what they think has changed since then, both in the industry and in themselves as directors.

‘I think, for us, our interests have shifted,’ Peter says.

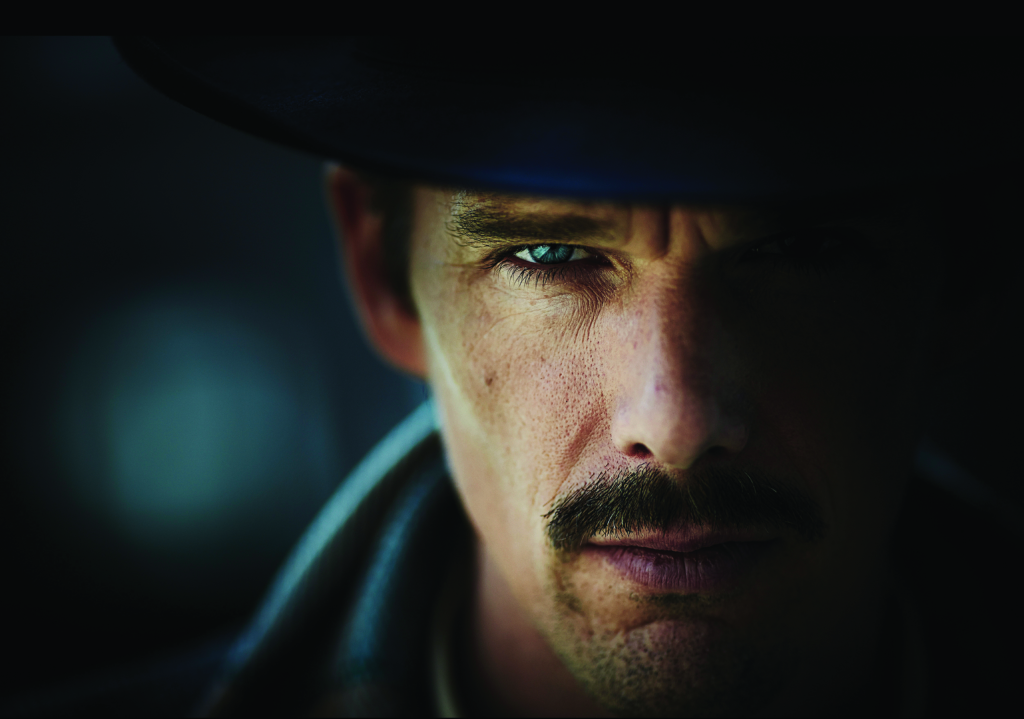

I love Undead. It’s a beautifully flawed splatterfest. It’s so rough around the edges, but I love that – I’m so proud of that film; it was so hard to make. But am I going to get excited about blowing up zombie heads for a month? These days, I don’t know. What Michael and I loved about Predestination was that it’s about performance, and it lives or dies by its performances. We’ve grown to really love working with actors and having that collaborative relationship […] and working with Ethan [Hawke, who plays the barman and whom they’d previously worked with on Daybreakers] is like that – we’re all working together to build a performance, build a story.

‘What Michael and I loved about Predestination was that it’s about performance, and it lives or dies by its performances.’

– Peter Spierig

They note that there was a small flood of genre filmmakers that broke through in their wake – Aussie horror showing a particular uptick – but it’s the really big cinematic picture that has changed in the last ten years.

‘Undead was a film that got released theatrically all over the world. Today, that wouldn’t happen,’ offers Michael.

That film would not go theatrically around the world today, and that’s simply because the landscape of what it means to play in a cinema has changed so that there’s less and less indie films, unfortunately, that get theatrical releases, and the whole [video-on-demand] market has become a massive thing for the smaller movies. It seems like there’s more and more huge films, and it’s just harder to break through those behemoths.

Peter reflects, ‘Ten years ago, when we did Undead, there were a lot of Australian films that were … bleak.’

‘The bleak suburban drama,’ Michael adds.

‘It definitely has changed and I think that’s a good thing,’ Peter concludes. ‘It’s just a question of whether audiences actually go and see those films, and that’s the hardest thing of all. We’re doing more genre pictures, but are audiences wanting to see them?’

*

It’s 2014, three weeks after the interview has concluded. I’m re-reading my transcript and thinking about how Michael and Peter have changed since 2003. I remember them starting my first interview by offering to mention their names before each comment, and I’d noticed they didn’t bother doing that this time. I can’t say I blame them. It was a minor courtesy that probably got tiresome after a while, and I’m sure I’ll figure out how to attribute who said what.

Then I look at the transcript carefully.

I note just how casually they keep mentioning each other’s names all the way through our conversation. And I smile.

As Predestination demonstrates, the twin directors have gotten better – more subtle – at what they do.

http://www.pinnaclefilms.com.au/Product/Details/5ba7f4e8-d08a-4c4c-871c-a11100ec8a63

Endnotes

| 1 | The Spierigs’ 2003 responses that follow were first published in Dave Hoskin, ‘The Sharing of One Brain: A Conversation with the Spierig Brothers’, Metro, no. 138, 2003, p. 24. |

|---|