Japanese Story, the second feature film from the writer/director/producer team of Alison Tilson, Sue Brooks and Sue Maslin, recently opened the 52nd Melbourne International Film Festival. As with their feature debut Road to Nhill (1997), Japanese Story could be broadly described as a road movie. But while both films foreground the physical and emotional journeys of their respective characters, they also expand the genre in surprising directions. Where Road to Nhill is in equal parts road movie, black comedy and geriatric drama, the cross-cultural romance at the heart of Japanese Story reconfigures the genre in a rather different way.

The first images in Japanese Story bear a striking resemblance to the opening scenes in Road to Nhill. In both films, a series of aerial shots depict the countryside – the Western Australian Pilbara Desert and rural Victoria respectively – from a deliberately aestheticized perspective. The wide, brown land, abstracted into a series of pleasing patterns and textures, is gradually reduced to a human scale. It is a view of the landscape that has a longstanding tradition in the Australian cinema, foregrounding as it does, the ambivalent attractions of a vast and at times unforgiving continent.

From Jedda (Charles Chauvel, 1955) to Walkabout (Nicholas Roeg, 1971), Priscilla Queen of the Desert (Stephan Elliott, 1994) to The Tracker (Rolf de Heer, 2002), characters in Australian films have experienced both tragedy and epiphany in the setting of the Australian outback. As Sue Brooks has observed:

A really popular story in Australia is that people go into the desert and something happens to change their lives. A lot of films do it, maybe because Australians have profound emotional connections with the desert.[1]Catherine Bremer, ‘Japanese Story twist takes Cannes by surprise’, The Age, 22 May 2003, <https://www.theage.com.au/entertainment/movies/japanese-story-twist-takes-cannes-by-surprise-20030522-gdvqwy.html>.

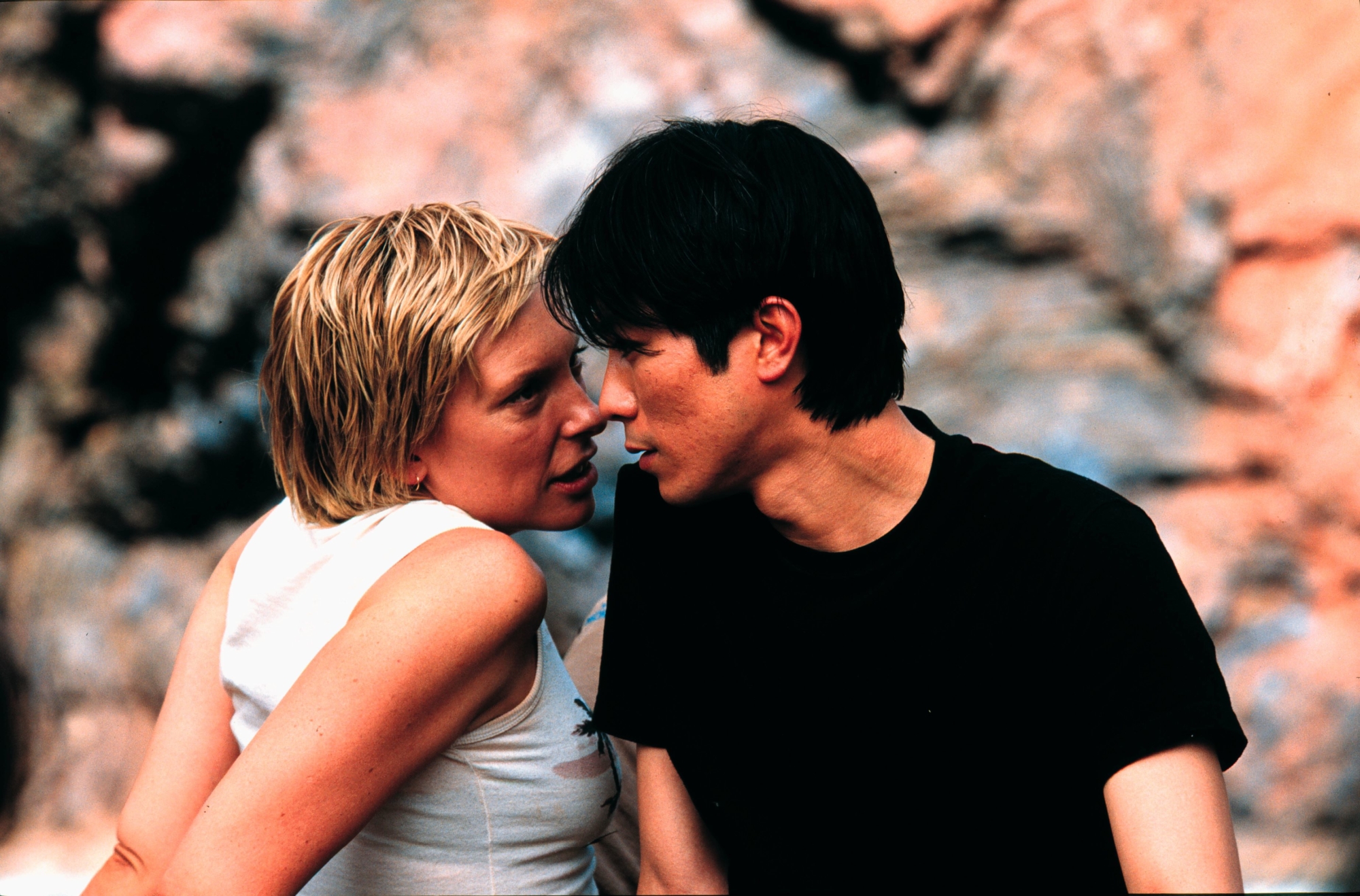

In her take on this formative national narrative, Alison Tilson places an improbable duo in a contemporary outback setting. Australian geologist Sandy Edwards (Toni Collette) and Japanese businessman Tachibana Hiromitsu (Gotaro Tsunashima) are thrown together by force of circumstance. Sandy has reluctantly agreed to show Hiromitsu around the Pilbara region, hoping he will be interested in the geology software she has been developing with her business partner Baird (Matthew Dyktynski).

The two are temperamentally unsuited from the start. Impatient with what she sees as Hiromitsu’s excessive formality, Sandy is riled by the latter’s condescending assumption that she is merely his driver. She describes him to Baird as ‘boring, and a jerk’. Hiromitsu’s assessment is even less flattering. He tells a work colleague Sandy is loud, aggressive and very stubborn; by implication, the antithesis of her decorous Japanese counterparts.

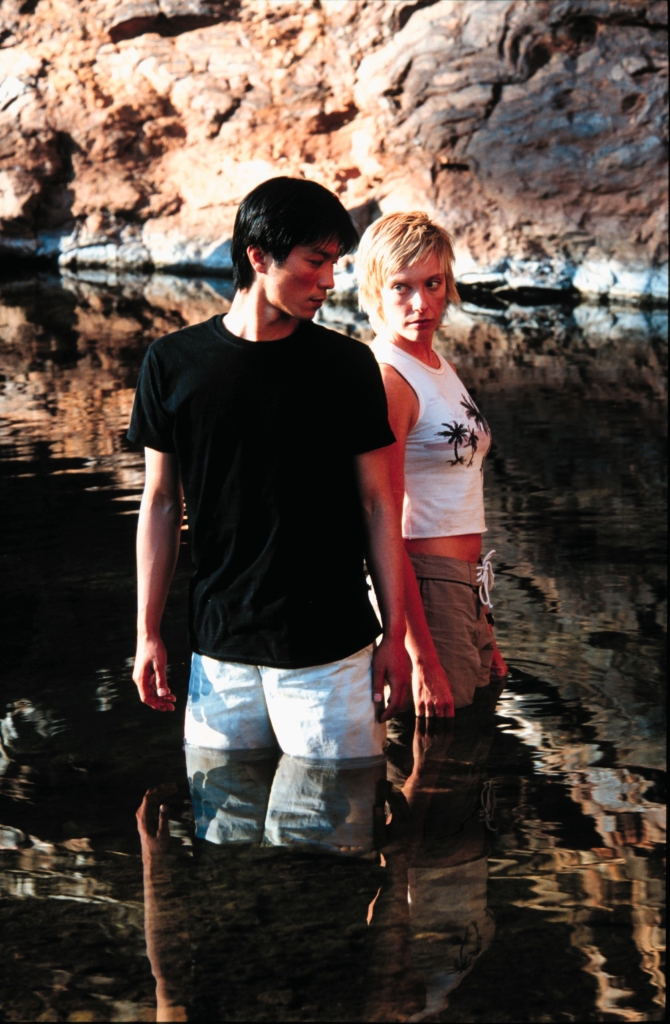

The trip strikes almost immediate trouble when Hiromitsu insists they take the road less traveled, and their four wheel drive vehicle becomes intractably bogged. When Sandy’s efforts to retrieve the car fail, Hiromitsu’s well developed sense of pride will not allow her to call for help. Stranded overnight in the sub zero temperatures of the Pilbara Desert, the two barely speak. Working together the next morning, they eventually free the vehicle and resume their trip. The incident functions as an epiphany of sorts, a shared and strangely liberating experience that begins to draw the two characters together.

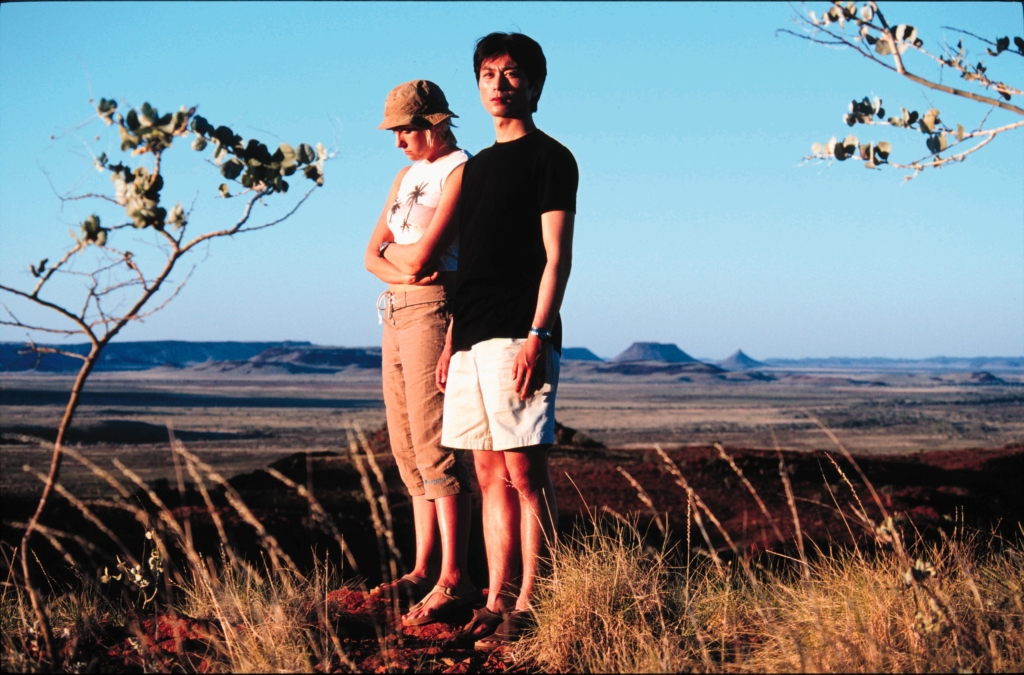

As the journey progresses, taking in spectacular stretches of the Pilbara desert and a vast mining complex, Sandy’s animosity lessens and Hiromitsu’s reserve dissipates. They gradually realize that the emotional ties that bind them are greater than the cultural differences dividing them. The shocking event which then occurs, has ramifications that reverberate from the Pilbara to Kyoto.

While Japanese Story fits self-evidently into the road movie tradition, a genre with numerous Australian examples, generic considerations are perhaps a less interesting way of approaching the film. It is the cross-cultural framework and the dramatic oppositions represented by the lead characters, which offer a more productive way of contextualizing the film.

Isolating a Japanese and Australian character in the outback is a dramatic device that is not without precedent in contemporary Australian cinema. Two recent films, Heaven’s Burning (Craig Lahiff, 1997) and The Goddess of 1967 (Clara Law, 2001), have featured young Australian-Japanese couples, who for various reasons, find themselves traveling through the remote Australian countryside.

In the former, young Japanese honeymooner Midori (Youki Kudoh), fakes her own abduction and then becomes inadvertently caught up in a Sydney bank robbery. Taken hostage, she is saved from certain death by the getaway driver Colin (Russell Crowe). The two then embark on a Bonnie and Clyde-inspired robbing spree across rural NSW, with the police and Midori’s jilted husband in hot pursuit. In the course of the journey, Midori is rapidly transformed from a demure, conventionally dressed Japanese woman into an anarchic, peroxide blonde, gun-toting bank robber. Midori’s emotional liberation is complete when she and Colin fall in love, but the romance, as in the best Bonnie and Clyde tradition, is inevitably doomed.

The Goddess of 1967 also employs a criminal premise in order to literally drive its two lead characters into the Australian outback. JM (Rikiya Kurakawa) is a young Tokyo salary man, whose solitary life is ameliorated by his dreams of owning a classic, late 1960s model Citroen, the legendary DS. Finding one for sale online, he travels to Australia to finalize the purchase. As with Midori, JM becomes embroiled in the aftermath of a violent crime and flees in the DS, accompanied by a young, blind Australian woman, BG (Rose Byrne).

To find the Citroen’s owner, they travel deep into the Australian outback, ‘to a place not on the map’. Along the way, JM and BG encounter strange, surreal landscapes, confront personal demons and ultimately fall in love. As with both Hiromitsu and Midori, JM undergoes a personal transformation. And as with the former two characters, it is arguably the liberating effect of the outback, as much as the company of his Australian friend, which effects this transformation.

In each of the aforementioned films, the dramatic catalyst is twofold; the pairing of a Japanese and Australian character, and the couple’s subsequent retreat into the remote Australian countryside. The coupling of Japanese and Australian protagonists is, in many ways, an expedient move. In terms of national character, the potential for conflict could not be more extreme. Notions of Japanese formality, strict social etiquette and a conscientious work ethic find their antithesis in the famed (or infamous) Australian inclination towards informality, relaxed social customs and a correspondingly laid back lifestyle.

While these are questionable assumptions around national character and identity, they establish useful disparities between the central protagonists, in terms of language, behaviour and belief. In Heaven’s Burning, Midori’s conservative appearance and initial reticence provide a perfect foil for Colin’s rugged, macho self-possession. In The Goddess of 1967, JM is the emotionally restrained product of an aggressively urban Tokyo existence, in marked contrast to the excitable, unsophisticated, backwoods- born and bred BG.

In Japanese Story, the differences between Hiromitsu and Sandy are spelt out in predictable fashion. When he first appears, Hiromitsu is immaculate in suit and tie, regardless of the fact he is driving alone in the heat of the outback. Hiromitsu photographs himself and the landscape obsessively, and exchanges business cards and social niceties with extreme deference. He is quickly established as that most conventional of Japanese character types, a contradictory mix of arrogance and extreme civility.

Early scenes with Sandy indicate that she is a smart, assertive if somewhat abrasive personality, a woman who speaks her mind and has the no frills, Bonds and Blundstones wardrobe to match. At a loss in the kitchen but adept with off road vehicles and sophisticated software, Sandy talks fast, smokes relentlessly and doesn’t stand on ceremony.

The fundamental distinctions in character and appearance established in early scenes, are an accurate indication of the disappointingly blunt articulation of cultural difference found throughout Japanese Story. But more of that later. What is equally, if not more telling, is the lack of conviction that ultimately characterizes the relationship between Sandy and Hiromitsu.

Once they have overcome a night in the desert and their mutual antipathy, Sandy and Hiromitsu’s growing rapport is established through a series of exchanges that supposedly bridge the cultural and emotional distance between them. A few subtleties of language and culture are thus ironed out over a greasy meal at a roadhouse cafe. Shortly thereafter, the two spend the night together. While the sex scene and its awkward aftermath are handled with considerable originality and sensitivity, it is the earlier failure to persuade us that these two characters have really connected that undermines the cross-cultural romance at the heart of Japanese Story.

The failure to convince us of a genuine affinity between Sandy and Hiromitsu can be traced to problems with individual characterization. Despite the considerable amount of screen time devoted to establishing the central characters, Sandy and Hiromitsu remain frustratingly opaque. While Hiromitsu is initially presented as a compendium of stereotypically Japanese attributes, there is some attempt to develop his character. In the course of the film, Hiromitsu sheds both his formal attire and some of his emotional reserve. We learn, albeit in a limited fashion, about his family life and aspirations. This is not the case with the Collette’s character, whose perspective ultimately dominates Japanese Story.

Present in virtually every scene, Sandy carries the psychological weight of the narrative. It is clearly her emotional trajectory that centres the film. From early, establishing scenes, Sandy is marked as something of a troubled personality. There is a rebarbative quality to her character, manifested in her defensive encounters with work colleagues, friends and particularly, her mother (Lynette Curran). While there is an occasional, fleeting reference to her past history (a personal as well as professional relationship with Baird), very little back story is revealed.

Put simply, Sandy is an unlikeable character with whom it is consistently difficult to identify. It is never made clear why she is such a brittle personality and subsequent events, which test her character in every conceivable way, do not work to sufficiently engage our sympathies with her dilemmas. Producer Sue Maslin has suggested that Sandy’s work as a geologist represents the metaphoric equivalent of her emotional journey.[2]Sue Maslin, Press Kit, Japanese Story, p. 5. In both a personal and professional sense, the aptly named Sandy therefore deals only with the surface of things, but is eventually forced to reckon with what lies beneath. While this is an appealing enough metaphor, particularly in the symbolic setting of the ancient Pilbara Desert, the film never quite manages to persuade us that Sandy is any more credible as an emotionally complex individual than she is as a geology software expert.

Sandy’s equivocal appeal may also have something to do with Collette’s performance, which is uneven to say the least. In early scenes she seems ill at ease, overplaying Sandy’s abrasiveness (which may contribute to her character’s strongly unsympathetic first impression). In later, emotionally demanding moments, there is a forced, almost self-conscious quality to her performance. A versatile actor, who in recent times has made a vivid impression even in minor roles (her extraordinary, scene-stealing turn in The Hours, [Stephen Daldry, 2003]), Collette’s work in Japanese Story is a strangely ambivalent effort.

The equivocal appeal of the central characters in Japanese Story might also be explained by the way in which they are consistently required to denote cultural difference. Despite the film’s emphatic title, Japanese Story offers a surprisingly circumscribed approach to the notion of difference that the Japanese characters, Hiromitsu in particular, are made to represent.

Hiromitsu’s ‘Japaneseness’ is repeatedly reduced to simplistic symbols or self-evident platitudes. Thus, Japanese pride is signified by Hiromitsu’s refusal to accept help when the car is bogged; Japanese orderliness by his excessive neatness. The Japanese penchant for business card exchange is played out in scenes involving Hiromitsu and mining workers which take on a near farcical quality.

Gazing at the vast panorama of the Pilbara Desert, Hiromitsu is made to observe that ‘Australia has lots of space and no people while Japan has many people and no space’. A singularly reductive distinction between the two national cultures, it is one of a series of rather prosaic observations on the subject of cultural difference that characterize Japanese Story.

While The Goddess of 1967 is in some respects a problematic film, Clara Law’s Japanese protagonist conveys genuine psychological complexity. JM’s take on Japanese life contrasts with Hiromitsu’s pedestrian assessment. A series of intriguing flashbacks, incorporating atmospheric cinematography and exquisite graphics, reinforces JM’s observation that ‘Living in Tokyo is like living on Mars’. An intriguing character, JM’s ‘Japaneseness’ is defined as much by his obsession with a French screen hero and his car (Alain Delon in Jean-Pierre Melville’s Le Samourai, [Melville, 1967]) as any stereotypically nationalistic traits.

If the central characters in Japanese Story struggle to command our full attention, the Australian landscape has no such difficulty. Described by cinematographer Ian Baker as the third ‘lead character’ in the film, the varied and spectacular locations in Japanese Story are used to full and dramatic effect.[3]Ian Baker, Press Kit, Japanese Story, p. 11. From the lyrical opening aerial shots to the flat but stunning vistas on the endless open roads, the Westen Australian outback dominates the frame. As with Heaven’s Burning and The Goddess of 1967, the landscape in Japanese Story has a tangible effect on the foreign protagonist in the story. Speeding through the deserted countryside in Heaven’s Burning, Midori’s ecstatic ‘I can breathe, I can breathe’, is echoed in Hiromitsu’s equally heartfelt, ‘there is so much space and my heart is open’.

This emphasis on the landscape also reinforces the connection between Japanese Story and the first Tilson/Brooks/Maslin collaboration, Road to Nhill. While the latter takes place in the rural rather than remote Australian countryside, and features a large ensemble cast, it shares a number of formal and thematic preoccupations with Japanese Story. As noted earlier, both films are informed by elements of the road movie genre. Unsurprisingly, the catalyst for action in both films is a car ‘incident’.

In Road to Nhill, a car with four older female passengers overturns. The spectacular accident generates a complex, multi-strand narrative, each story invested with comedy and pathos. While humour defines the film for the most part, Road to Nhill’s understated tone of melancholy culminates in a tragic and moving denouement involving one of the characters.

Tilson’s screenplays for both Road to Nhill and Japanese Story are arguably underpinned by a concern with mortality. The opening scene in Road to Nhill has Phillip Adams intoning, in mock serious, voice-of-God style, about the one certainty in life – death. In early scenes in Japanese Story, Sandy’s mother obsessively scans the obituary notices, collecting tributes to dead friends in a scrapbook that she hopes will eventually become the memorial to her own life. Her response to Sandy’s dismissive attitude is to observe that ‘death is a part of life’, a part that can’t be avoided.

While it is difficult to discuss Japanese Story in this context without revealing significant plot developments, the latter part of the film, as with Road to Nhill, is preoccupied with intense emotional and psychological reckoning in the aftermath of a tragic event. In Japanese Story, it is this ‘third act’ which ultimately offers the most substantial and dramatically satisfying moments in the film.

The title of Tilson’s screenplay is curious, even vaguely misleading – why ‘Japanese’ Story? It is a tale told more particularly from Sandy’s perspective – an Australian Story. There is also a certain, and perhaps deliberate, naïveté in the title. In its simplicity it suggests something generic, uncomplicated, even fable-like; a ‘story’ with a proper beginning, middle and end. The ambiguous title is in fact an accurate indication of the film-makers’ ambitions.

As a road movie, Japanese Story makes a dramatic departure from the form; as a romance, it imposes a startling twist on the conventional romantic trajectory. The film-makers attempt to both present a simple story and complicate a number of generic structures. But where Road to Nhill successfully juggled comic and dramatic registers, Japanese Story ultimately falls short of both the formal and emotional complexity it clearly aspires to.

Endnotes

| 1 | Catherine Bremer, ‘Japanese Story twist takes Cannes by surprise’, The Age, 22 May 2003, <https://www.theage.com.au/entertainment/movies/japanese-story-twist-takes-cannes-by-surprise-20030522-gdvqwy.html>. |

|---|---|

| 2 | Sue Maslin, Press Kit, Japanese Story, p. 5. |

| 3 | Ian Baker, Press Kit, Japanese Story, p. 11. |