In Dr Plonk and Passio, filmmakers Rolf de Heer and Paolo Cherchi Usai have assumed what might be called a revisionist stance by taking their craft back to the good old days of silent cinema. Relying solely on the interaction of projected black and white images and live music, de Heer and Cherchi Usai have forced themselves to explore to the foundations of their medium without the safety net or diversions offered by new technologies. The discoveries that both have made in this process point to contrasting but equally important values in cinema. Where de Heer’s film bears the rudimentary dynamics of visual storytelling, Cherchi Usai’s work surrenders its narrative autonomy to the more refined structures of music and text, exposing the illusion we attach to the moving image.

The Slapstick Apocalypse: Dr Plonk

Dr Plonk takes on a rather substantial subject for a slapstick comedy: it is a film about the end of the world. It tells the story of one Dr Plonk (Nigel Martin), an eminent Australian scientist who, a century ago, calculated the date of the apocalypse as being sometime in 2008. Unable to convince federal politicians with his mathematical formula, Plonk embarks on a scientific expedition to garner hard evidence. With the aid of Mrs Plonk (Magda Szubanski), his deaf-mute assistant Paulus (Paul Blackwell), and nutty dog Tiberius (Reg), Plonk constructs a time machine that will transport him to the world of the future. After a few hiccups along the way, he reaches his destination and sets out on his search for proof.

It doesn’t take the doctor long to be convinced of his theory’s validity. The Australia he observes in 2008 is rife with evidence of an imminent end. Heavily armed police swarm the streets in plague proportions while families sit silently in their living rooms, fixed motionlessly agape in front of the apocalyptic images generated by their televisions. Gripped by fear, politicians have become a protected species and are vigilantly guarded from the public. Geniality within public spaces is viewed with particular mistrust, especially if you are funny looking. Suspecting the worst of people is the order of the day in this future nation. As Plonk’s message of admonition to his successors becomes more and more desperate, he chooses to take extreme measures and gives up his chances of civic freedom in the process.

Though it all might sound a bit grim, Dr Plonk is a very funny film. Taking inspiration from Chaplin, de Heer delivers his serious social message with an array of visual gags and daft plot turnarounds that involve the audience in a pure and simple comic experience. Denying his audience sound and rapid cutting, he encourages us to attend to the possibilities of each shot. Who will enter the frame? What side of the frame will they enter from? Whose feet are those sticking out of the bottom right corner of the screen? Is Mrs Plonk in the room or has she gone to the kitchen? De Heer exploits these uncertainties by setting up our expectations and then subverting them. (Yes, he reveals, she was in the room, but not where you thought she was.)

Though it all might sound a bit grim, Dr Plonk is a very funny film. Taking inspiration from Chaplin, de Heer delivers his serious social message with an array of visual gags and daft plot turnarounds that involve the audience in a pure and simple comic experience.

At the film’s premiere on the festival’s closing night, this most primitive of comic strategies generated a playful and joyous response from the audience. A sudden clash of heads or boot up a derrière sparked howls of laughter rarely inspired by even the most sophisticated of satires. While perhaps merely indicative of the South Australian public’s preference, this enthusiastic audience response can also be explained by reference to the silent film’s participatory aspect. If a film entails fewer diversions – no spoken dialogue, fewer cuts and changes of angle and scene – the audience themselves will be obliged to assume a more active involvement with the unfolding action. They will watch more closely, make predictions and wait eagerly for the punch line. Indeed, the audience’s very posture will change. Normally slouched and reflective in the cinema, I noticed myself sitting upright, often leaning forwards to egg the comedy on. Some people in the cinema even shouted at the screen, behaving as if the projected images were real people. I was reminded here of the fear that audiences reportedly experienced on witnessing the Lumière brothers’ L’Arrivée d’un train en gare de La Ciotat in 1895. Confronted with the image of an oncoming train, they fled the makeshift cinema in panic. Could it be that films without sound are more real than those with? Most people have assumed the opposite.

The visual humour of Dr Plonk is aided and abetted by some wonderful acting. Unable to rely on the power of the voice, the film’s players use the limited means at their disposal to resurrect a forgotten, and perhaps superior, thespian art. Street performer Nigel Martin gives a terrific rendition as Plonk. His gestures and expressions skilfully walk the line between emphasis and overacting to punctuate and colour the action at just the right moments. Szubanski, as always, is a comic delight. Her ability to find new dimensions in self-ridicule seemingly knows no bounds. Heeding what is perhaps a cardinal rule of slapstick, de Heer also gives ample screen time to Reg the dog, whose acrobatics possibly outshine those of Rin Tin Tin.

The film’s score, composed by Graham Tardif, contributes equally to the carnival atmosphere. Reacting at once to the trips and tumbles, it mickey-mouses the screen action with a buoyantly syncopated arrangement of piano, accordion, violin and double bass. The highly talented Melbourne group The Stilletto Sisters performed the composition live at the film’s premiere, receiving at its end what seemed an endless shower of applause. Where the work of film composers today goes unrecognized by most, this event revealed the vitality of music as the natural kin of the projected image.

While not as culturally significant as Ten Canoes (Rolf de Heer, 2006), Dr Plonk reaffirms de Heer’s status as Australia’s most interesting narrative filmmaker. Supposedly, the idea for this film came with his discovery of 20,000 feet of expired film stock that he could not bear to waste. Shooting a film in black and white was the obvious solution. And so Dr Plonk was born. Young filmmakers overwhelmed by the many obstructions imposed by the industry can find much to learn in de Heer’s kind of pragmatism. Indeed, since its earliest days, most professional narrative filmmaking has been about the search for practical solutions. The output of silent pioneers like D.W. Griffith and Louis Feuillade testifies to this. They each made hundreds of films with the uncomplicated intention of telling a story with the materials at hand (and, of course, earning a living for themselves and their casts and crews). Working out of his own Adelaide-based production company, de Heer has now completed his eleventh feature, a remarkable number for an Australian filmmaker today, but eerily few when compared to the standards of the past. Whether he remains an irregularity in the Australian film industry will be an issue of real significance for feature filmmaking in this country. That is, of course, if we don’t all blow ourselves up in the meantime …

The Archivist Strikes Back: Passio

The second and more serious film of the pair, Passio is an arrangement of archival footage from the earliest years of cinema by the director of Australia’s National Film and Sound Archive, Paolo Cherchi Usai. New to filmmaking, Cherchi Usai is a highly distinguished archivist and scholar of film who is particularly interested in the history of our civilisation’s obsession with image production and consumption. Like many historians, Cherchi Usai has a fascination with the early silent period. (His book Burning Passions is perhaps the definitive text on the subject.) In cinema’s origins, I suspect, he hopes to discover the source of the enigma that has enraptured us all.

As the film’s opening credits make clear, Passio is ‘to be projected as an accompaniment to Arvo Pärt’s Passio Domini Nostri Jesu Christi secundum Joannem’ (‘The Passion of Our Lord Jesus Christ according to John’). Composed by Pärt in 1982 for choir and orchestral quintet, this musical piece is structured around a Latin recitation of the apostle John’s description of Christ’s arrest, judgement and crucifixion (John 18:01–19:30). It was the first significant religious piece composed by Pärt after he left his native Estonia, and remains his most widely cherished work. Choral conductor Paul Hillier directed the composition’s definitive performance in 1988. Hillier returned to the role of conductor at the Adelaide Town Hall to direct the Adelaide Chamber singers and members of the Adelaide Symphony Orchestra.

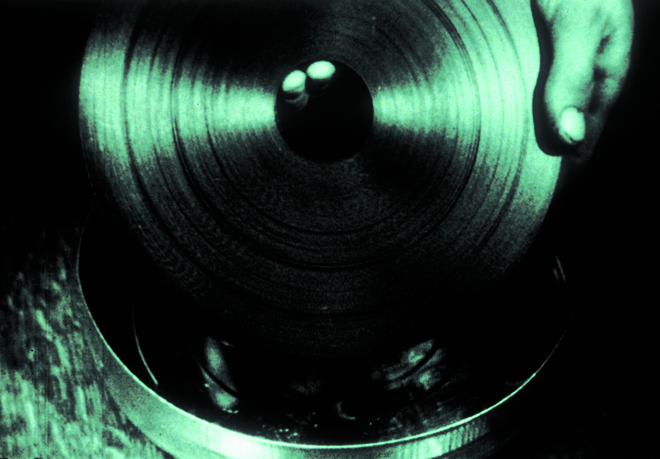

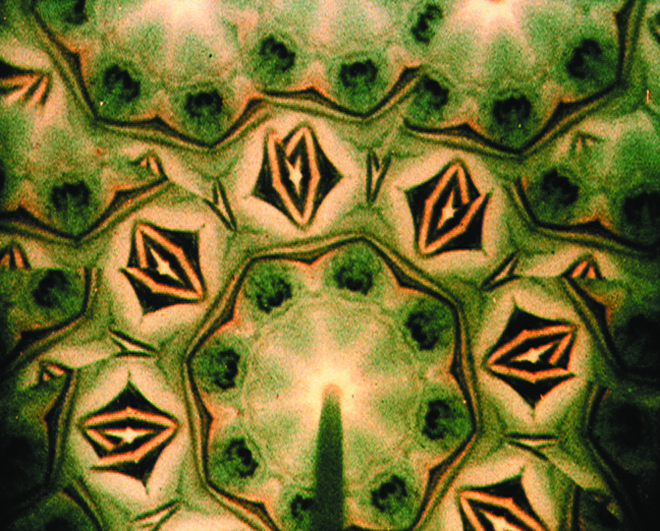

Cherchi Usai’s proclaimed goal for Passio is to forge a dialogue between image, music and text. At a rhythmic level he achieves this by splicing the film’s images, black screens and calligraphic script (written onto celluloid) in time with the music’s rigidly organised changes. (The length of notes and silences in Pärt’s score all accord with a highly systematised order based on the number of syllables in the Biblical text.) Cherchi Usai’s motivation behind the inclusion of certain images is, however, far more obscure. Juxtaposing footage of atrocities, salamanders and kaleidoscopes, the filmmaker’s selection process strikes the viewer as intuitive, even accidental – such is the unconventionality of this film.

Behind their apparent arbitrariness, though, Passio’s images do conform to a traditional hierarchy. It is no coincidence that John’s Gospel begins, ‘In the beginning was the Word.’ In referring directly to Pärt’s score as his structural guide, Cherchi Usai has consciously subordinated his visual arrangement to the music, in the same way that Pärt subordinated his composition to John’s scripture (and John’s in turn to the creating Word). Pärt himself has made this artistic principle clear, stating that the Gospel text is ‘more important than the music … the text is stronger and has given food for hundreds and thousands of composers, and it will continue so’.

Arriving well after the Word, the cinematic element of Passio is used to express new dimensions, definable perhaps as visceral dimensions. In his writings on film, Cherchi Usai emphasizes the organic nature of celluloid and its adhesives. For him, the matterof images is not a simulation, it is a chemical reaction projected by light. Rather than a tool of fiction, cinema for Cherchi Usai is a way of seeing this world anew. Accordingly, Passio reveals his commitment to the estrangement effect that so fascinated many pioneers of the early silent period. When captured on celluloid, the dimensions of physical existence can be magnified, warped and divided. The human body somehow escapes its routine forms, and when projected onto a screen jumps out of its skin to be reflected back to the audience as an infinitely more fascinating, disturbing or beautiful object. Passio brings this effect very much to the fore. Human flesh and bones, over a century old, are scrutinized and dissected. Like the film itself, the human body is presented as matter, as an organism that dies. It is a perspective that very few people today are willing to adopt.

Rather than a tool of fiction, cinema for Cherchi Usai is a way of seeing this world anew. Accordingly, Passio reveals his commitment to the estrangement effect that so fascinated many pioneers of the early silent period.

At its premiere during the opening weekend of the festival, Passio received radically mixed responses. For many, including myself, the simple experience of hearing and seeing such an unconventional and serious event within the confines of the city’s staunch Town Hall was itself sufficiently cathartic. For some others, the film’s images of human births, dead children and dissected eyeballs pushed the envelope well beyond tearing point. Attacked for the film’s visceral nature, Cherchi Usai has suggested an altogether different reason for the negative public response. From his perspective, far more disturbing to the contemporary audience is Passio’s visual arrangement itself. ‘What has been described as unsettling is the result of a different mental pattern,’ he has said.

But perhaps even more unsettling for the digital consumer is the mortality that Cherchi Usai has imposed on his creation. By printing only six reels (each hand-coloured in a different hue) and then destroying the negative, he has stayed true to his belief that each version of a film is a biological entity. In his words, ‘Every print of a film is a unique object with its own physical and aesthetic characteristics.’[1]Paolo Cherchi Usai, Burning Passions (revised edition), bfi Publishing, London, 2000, p.65. Like our bodies, Passio will eventually dissolve and be lost forever. Some will probably be glad to see it go. Others will remember its images with sober thanks.

Endnotes

| 1 | Paolo Cherchi Usai, Burning Passions (revised edition), bfi Publishing, London, 2000, p.65. |

|---|