As highlighted throughout Mark Hartley’s entertaining, exhaustive documentary Not Quite Hollywood: The Wild, Untold Story of Ozploitation! (2008; M158), Australian genre films faced substantial prejudice during their rise in the 1970s and 1980s. After all, they had the misfortune of being released around the same time as such celebrated Australian New Wave titles as Picnic at Hanging Rock (Peter Weir, 1975; M35, M149, M193) and My Brilliant Career (Gillian Armstrong, 1979; M157). In the documentary, critic and social commentator Phillip Adams even admits: ‘Most of us were very snobby about genre films – there’s no question about it. You didn’t approve of them.’

This would perhaps explain Metro’s meagre coverage of genre during this period. Significantly, pre-eminent existential shocker Wake in Fright (Ted Kotcheff, 1971) didn’t receive analysis until almost a decade after its release – though it’s perhaps also worth mentioning that the film’s original print was lost for forty years. In this particular piece from 1980, however, Dennis Bowers regarded it as ‘undoubtedly one of the best films to have been made in Australia’, applauding how it extended on its overemphatic source novel to skilfully conjure subtle ambiguity that invited the viewer to draw their own interpretations (M51). Decades later, a 2009 analysis would shower similar praise on the now-recognised classic, with Dave Hoskin suggesting that the initial neglect of the film was justified by how too close for comfort its depiction of aggressive Aussie hospitality was for local cinema-goers of the time (M162). And, in 2017, Gabrielle O’Brien acknowledged howWake in Fright profoundly reshaped our national cinema outlook and actually inspired the budding auteurs of the Australian renaissance (M193).

In 1999, the essence of a cinematic ‘Australianness’ was discussed in an extensive interview with George Miller, who reflected on his original Mad Max series (1979–1985) and how it projected a quintessential alternative to the sanitised sense of national identity presented in those renowned 1970s period films (M123). In a similar vein, delving deep into the production history and hostile critical reception of the notorious Turkey Shoot (Brian Trenchard-Smith, 1982), a 2009 piece considered how, by that point in Australian cultural history, the Ozploitation period had become heralded as a golden age of local cinema (M162). This is arguably due to not just Hartley’s aforementioned eye-opening documentary, but also the success of homegrown genre products like Wolf Creek (Greg McLean, 2005; M145, M148, M150).

The point is that we’ve come a long way since the critical snobbery of the 1970s. In 2009, Metro published a two-part ‘Beyond the Cringe: Ozploitation and Australian Paracinema’ special feature (M161, M162). And, in 2014, the magazine dedicated close to half of its 180th issue to a one-off ‘Horror Down Under’ section, which paid serious attention to contemporary films like Wolf Creek 2 (McLean, 2013), The Babadook (Jennifer Kent, 2014)and Hartley’s own 2013 remake of Richard Franklin’s Ozploitation classic Patrick (1978). It also shed light on a slew of underappreciated 1980s genre films that were overlooked even in Not Quite Hollywood itself, and offered insights into horror distribution, reception and success both locally and overseas.

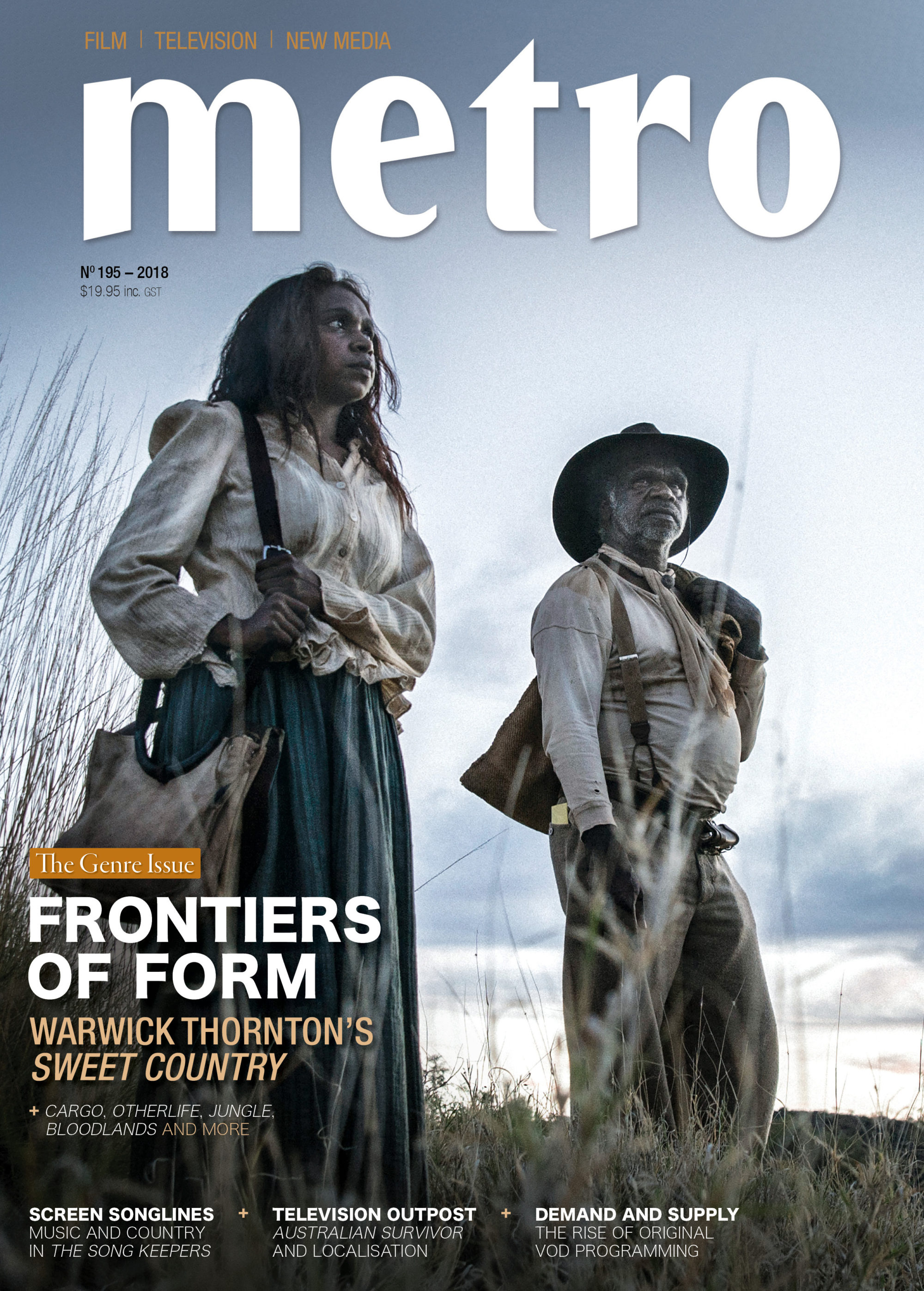

A spiritual successor to ‘Horror Down Under’ was 2018’s ‘Spotlight on Genre Film’ special-feature in issue 195, headlined by Warwick Thornton’s acclaimed western Sweet Country (2017). It also included, among other things, discussions on the rich cinematic world of Aussie sci-fi OtherLife (Ben C Lucas, 2017), the ‘quintessentially Australian’ zombie flick Cargo (Yolanda Ramke & Ben Howling, 2017), Albanian–Australian co-production horror title Bloodlands (Steven Kastrissios, 2017) and Canberra-shot sci-fi Blue World Order (Ché Baker & Dallas Bland, 2016), along with a retrospective essay on noir classic Dark City (Alex Proyas, 1998).

And it’s personally rewarding for this Queenslander to see that the reach of Australian genre has broadened, with the emergence of productions set in Brisbane and the Gold Coast over the past decade. These have seen accompanying attention in the pages of Metro: from an appreciative analysis of the inventively original world building of vampire flick Daybreakers (The Spierig Brothers, 2009; M164) to an interview with the director behind Chinese-box-office success story Bait (Kimble Rendall, 2012), which called for an increase in Aussie genre filmmaking to attract foreign markets and boost our industry (M175).

Fortunately, emerging filmmakers have been listening – and enthusiasm for the wild, untold stories of Aussie genre films shows no signs of dying soon.