You’ve got to admire the cheek of a director who calls his film simply Australia. It implies that what is going on in it is comprehensive enough, or at least symptomatic enough, to evoke the continent at large. Can it possibly live up to such a grandiose announcement of intention? There have been plenty of films named for cities (New York, New York [Martin Scorsese, 1977], Barcelona [Whit Stillman, 1994], most recently Paris [Cédric Klapisch, 2008]), but summoning a city seems a modest enterprise compared with a country or a continent (please sort us out, Senator Palin). D.W. Griffith in 1924 and Robert Downey Sr in 1986 had a go with America: neither director is today remembered for his attempt to aggrandize the personal into the national.

What we indubitably get in Baz Luhrmann’s new film is Australia as landscape – but landscape of a restricted kind. Does Luhrmann believe that it is only Dorothea Mackellarland (all ‘sweeping plains’ and ‘ragged mountain ranges’ and ‘droughts and flooding rains’) that the world at large will recognize as Australia? What he shows us is gorgeous beyond the shadow of a doubt – gorgeous, that is, to look at on a huge screen rather than to live in. It is, though, hardly the ‘Australia’ that most of its inhabitants will know intimately, living as we do in our urban fastnesses, but the pictorial arts have done their bit in instilling it as one of the sites of our yearning.

Perhaps it’s really a love story at heart, a love story in a huge setting that overpowers its fragile forays into intimacy. The film is wildly overlong at 165 minutes (are directors paying attention to my efforts to have films limited to ninety minutes and to their losing a finger for every minute over?), and, whatever its virtues, none of the film’s preoccupations are developed in such a way as to earn this running time. As a love story, and I’ll come back to this, Australia might easily become Luhrmann’s Ryan’s Daughter (1970), and look what that did to David Lean’s career.

But maybe Luhrmann’s real concern, the subject of portentous captions fore and aft, is the plight of Australia’s Aborigines and especially the tragedy of the ‘Stolen Generations’. Or the clash of the conflicting values of Aboriginal earth knowledge and white man’s greed and insensitivity? Or the idea of English upper-crust hauteur being humanized by rugged Australian values? Or the notion of Australia’s being pulled into nationhood by its response to foreign invasion?

Clearly this is a film in which a lot is going on, and further examination may indicate that Luhrmann has bitten off more than he can chew in the course of one, albeit mammoth-length, film. Coherence and dramatic development may be imperilled in the process.

None of the above is written in the spirit of one soured off by the massive hype that has surrounded this film, as if it were perhaps to put the Australian industry on a new international footing. I write as one who has greatly admired Luhrmann’s output to date. Think of the mixed modes of Strictly Ballroom (1992, musical crossed with mockumentary procedures), the transplanting of Shakespeare, verbally intact, from old Verona to twentieth-century Venice Beach, California, in Romeo + Juliet (1996) and the hybrid pyrotechnics of Moulin Rouge! (2001). These are each in their own way the work of a risk-taker, of an iconoclast with the courage (and capacity) of his iconoclasm, from concept to execution. Luhrmann has been that rare phenomenon in Australian cinema: one who has been willing to upset preconceptions and follow his own imaginative convictions with panache and persuasion.

His new film, though, may well be his most conventional to date, in spite of all the high-sounding verbiage that has been spilled in its promotion. For instance, the press kit tells us:

Australia is a metaphor for the feelings of mystery, romance and excitement conjured by a distant, exotic place where people can transform their lives, spirits can be reborn, and love conquers all.

Luhrmann himself has said of his wish to make an ‘epic’ of the kind he loved as a child:

I wanted to create a cinematic work that would be similarly inclusive because I feel passionately about having more inclusiveness in our lives. Bringing people together brings comfort to the heart and soul in this unpredictable world.[1]Australia, production notes, p.3.

Well, in box office terms he may well be proved to have achieved his aim, but in doing so I’d say he has sacrificed the dash and daring and sharpness of his earlier films.

Revisiting the epic

I’ve written elsewhere of what seems to be a resurgence of popular genres in recent Australian cinema,[2]Brian McFarlane, ‘Groupings and Gropings in Australian Cinema: Adi Wimmer’s Australian Film Cultures, Identities, Texts’, Overland, no. 193, Summer 2008, pp.95–96. drawing attention to the Antipodean spin given to the likes of the Western, the musical, the teen movie and the biopic. In view of this, I was interested to see what Luhrmann would make of the epic, a costly genre not common in Australian filmmaking. I wonder, though, whether he has actually made anything new and distinctive of the genre, and on the whole the answer seems to be ‘no’.

It’s not actually clear what he means by epic, citing as he does such disparate works as Gone with the Wind (Victor Fleming, 1939), Lawrence of Arabia (David Lean, 1962) and Titanic (James Cameron, 1997). Does he use the term simply to summon up very long, sprawling, expensive works? If so, then, yes, Australia qualifies. If, however, it refers to a work in which ‘the style is appropriately elevated to the greatness of the deeds’[3]Sylvan Barnet et al., A Dictionary of Literary Terms, Constable, London, 1964, p.60. that carry the narrative, then that requires only a qualified answer here. So does the extent to which the film conforms to the Brechtian idea of ‘the objectivity of epic narrative’,[4]M.H. Abrams, A Glossary of Literary Terms, 4th edition, Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1981, p.52. in which the events are put before us so as to encourage criticism rather than acceptance of the social conditions represented in the drama. To turn more specifically to the idea of the ‘film epic’, Jeffrey Richards has recently argued for the importance of the way historical epics give ‘the events a contemporary resonance by constructing them as an explicit commentary’ on the events of the period in which they are made.[5]Jeffrey Richards, Hollywood’s Ancient Worlds, Continuum, London, 2008, p.1.

It is not Luhrmann’s fault if the film has been trumpeted in ways that would have made the Second Coming seem disappointing, but as he is on record as wanting to produce a work in the epic mode, it is not inappropriate to consider what that might mean and how far the film lives up to such expectations. If Australia does exhibit epic characteristics, its lineage is less those films to which the descriptor is usually applied than that of the large-scale Westerns. Its cattle drive inevitably recalls Red River (Howard Hawks, 1948) and its scenic grandeurs invoke the memory of such Fordian masterworks as The Searchers (John Ford, 1956) and Cheyenne Autumn (John Ford, 1964), the interracial conflict of these latter also echoed in Australia. There is even a cultured outback drunk, Kipling Flynn (Jack Thompson), whose lineage stretches at least back to Thomas Mitchell in Stagecoach (John Ford, 1939).

If Australia does exhibit epic characteristics, its lineage is less those films to which the descriptor is usually applied than that of the large-scale Westerns.

But while there are some stunning shots of a vast herd of cattle as it is being driven to the port of Darwin, as a ‘Western epic’ the film lacks the power and threat of The Proposition (John Hillcoat, 2005), the previous Australian film which sought to revitalize the Western genre in a new location. Essentially, the film shows interest in some Big Themes but doesn’t sufficiently articulate them in terms of character and action.

A curious lack of chemistry

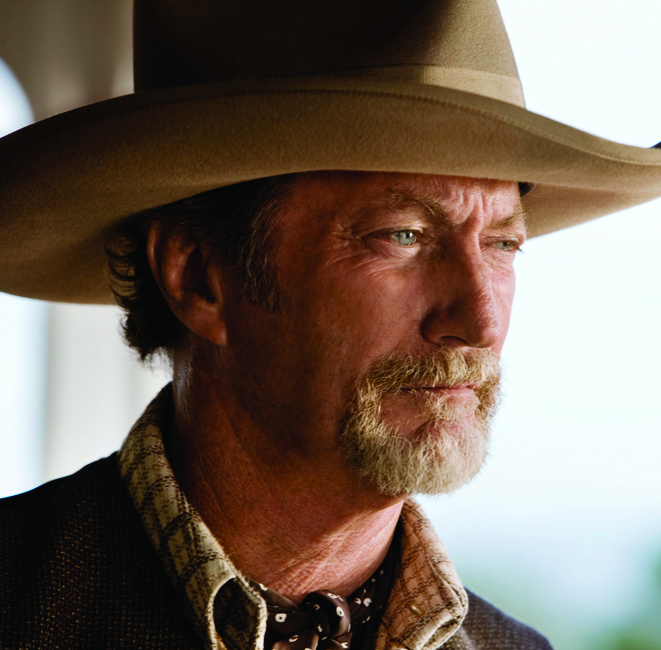

How does Australia measure up as a love story? It clearly counts on the star power of Nicole Kidman and Hugh Jackman in this respect, but they are at the service of a screenplay that delineates and motivates them too meagrely. As everyone probably knows by now, Kidman plays a haughty English aristocrat, Lady Sarah Ashley, who comes to Australia in 1939 to see what her husband has been up to and to sell their huge outback property, the aptly if not subtly named ‘Faraway Downs’. She arrives in Darwin, where she is appalled at some very macho Australian behaviour that at one point involves her lingerie being scattered in the dusty street. To get to ‘Faraway’ she is driven by Jackman, a very independent type, not about to be cowed by an uppity English milady, and who answers only to ‘Drover’, a name that announces his work and perhaps his legendary status.

There is something very familiar in the way these two are being set up as a potential couple. You can almost imagine how the initial scenario might have read: ‘There was antagonism between them from the start’, as if they were some latter-day John Wayne/Maureen O’Hara duo. When Drover is not making such suave remarks to her as ‘I wouldn’t have it on with you if you were the only tart left in Australia’, he is offering philosophical gems like ‘In the end the only thing you really own is your story, so live a good one’. Well, gosh, how true. He is also presented, in all his rugged masculinity, as a man of liberal principles, correcting Sarah when she speaks of ‘the natives’. She will naturally come to rely on his drover’s capacities when she decides to move her cattle to Darwin to be shipped off for food for the troops, thus outwitting unscrupulous neighbouring cattle baron King Carney (Bryan Brown), who has his eye on Faraway. Drover, in his turn, will come to admire Sarah’s resilience and her maturing sympathies. At least, that’s what the screenplay (the work of such distinguished hands as Ronald Harwood, Richard Flanagan and Stuart Beattie – a cook or two too many?) seems to have in mind.

Sarah and Drover simply don’t work as a romantic couple, and this is as much due to the scripting as to the curious lack of chemistry between them. Kidman does well enough as Lady Ashley stalking about her English stately home in her stylish riding attire, barking out orders. She is described by someone as ‘a genuine aristocrat’ when she arrives in Darwin, and someone else, to signal the tough new world she’s come to, pronounces her ‘Not a bad-looking sheila’. One of the film’s oppositions is epitomized there in the contrasting modes of appraisal. This will be echoed, again none too subtly, in Drover’s long-held wish to ‘mate an English thoroughbred with an Australian bush brumby’, for which of course we read the two leads.

Their first kiss, ushered in with huge close-ups, is curiously devoid of passion, and there is a sex scene shot discreetly enough not to offend your Auntie Joan.

Kidman’s initially convincing accent soon wobbles somewhat, and disappears altogether with a speed that is scarcely credible. And talking of ‘speed’, her changes of heart are too arbitrary: you’d think that, in so long a film, there would have been time for a more believable softening of her brittle imperiousness. Jackman certainly looks like a leading man, is given a chance to display his well-muscled torso, and is a persuasive action hero, dealing authoritatively with cattle and stroppy pub types, but the script just doesn’t give him much help with the more intimate moments. Their first kiss, ushered in with huge close-ups, is curiously devoid of passion, and there is a sex scene shot discreetly enough not to offend your Auntie Joan. As if to compensate for this, it is followed – and this sort of editing move is par for the film’s course – by a wild tracking shot that takes in the post-‘wet’ renewal of the landscape.

The look and feel of Australia

The landscape of outback Australia is perhaps peculiarly amenable to the epic treatment. Again and again, the film offers vistas of craggy outcrops and endless dusty tracts (or of Darwin harbour) that are simply breathtaking to look at, but one becomes tired of having one’s breath taken away so predictably. By this I mean not only that one begins to intuit a vast panorama coming on, but also the ways in which these shifts of scale are rendered. A comparatively small moment will almost inevitably cut to a huge long-shot that seems to take in an area the size of Tasmania; not only that, cinematographer Mandy Walker can’t resist pulling up for these wide overhead shots, so that the camera’s procedures assume the status of nervous tic. This sounds ungrateful for some imposingly lit and composed vistas, but accompanied, as they too often are, by David Hirschfelder’s too-emphatic musical score, you begin to feel you are being coerced into admiration.

As to the look and sound of the film, the production and costume design by Luhrmann’s partner and collaborator Catherine Martin are less strikingly in evidence than in some of their earlier films but still contribute substantially to the film’s pleasures. Personally I have little knowledge of how women were dressing in the period of the film, but Martin’s designs skilfully differentiate among Kidman’s elegant raiment (on and off horseback), the ladies of the Darwin social ascendancy and the Aboriginal women in their unassuming dresses. And as to production design, Martin gives Faraway a look of credible English influence at work in an unlikely setting, describing how she set out to ‘achieve the major textural changes the homestead undergoes from the dilapidated state we first see it in, to the green oasis it eventually becomes’.[6]Australia, op. cit., p.5. Similarly, her recreation of various Darwin settings (in Bowen, Queensland, to be exact) in the period leading up to the Japanese invasion gives off an air of both authenticity and foreboding. Her work in fact is the key continuity with Luhrmann’s earlier films, and award nominations are surely as inevitable as they are deserved.

The sound of the film is less securely achieved, whether in some false notes struck in the dialogue or in the utterly eclectic scoring which takes in Cole Porter’s ‘Begin the Beguine’, ‘Waltzing Matilda’, snatches of Beethoven and, I was assured, Elgar, as well as the symbolically charged ‘Over the Rainbow’. Whereas musical eclecticism had served Moulin Rouge!’s drama and fantasy so well, here it gives a merely distractingly polyglot effect. Nevertheless, one of the most memorable moments in the film is that set in the open-air cinema at Darwin with The Wizard of Oz (Victor Fleming, 1939) playing, and Garland’s singing of that song to that mixed audience hints at possibilities and longings that confer an emotional intimacy and a thematic potency that ring truer than the film’s bigger ‘statements’.

The idea that the epic film should resonate with contemporary importance has perhaps been paid too heavy-handed a service in Australia’s dealings with Aboriginal life and its representation. The concept of the ‘Stolen Generations’ is one of the significant ideological issues of our time, but the film’s explicit foregrounding of it in opening and closing captions suggests that the liberal point of view hasn’t been tellingly enough dramatized in the film’s narrative texture. In fact, it has. The character of Nullah (Brandon Walters), the ‘half-caste’ child who is always in danger of being snatched away into the care of no doubt well-meaning even if misguided missioners, encapsulates the sense of non-belonging. Even so, the film feels a need to let him emphasize his problem of not ‘belonging’ anywhere, as if it didn’t trust the drama of the narrative to make this point. This is not to question the film’s liberal sentiments, chiefly articulated by Drover, whose Aboriginal wife has died because ‘white’ hospitals wouldn’t treat her tuberculosis, or in the pitiable abuse to which ‘half-caste’ children (cries of ‘creamy’) are routinely subjected. Further, one applauds the eloquent presence of such notable Aboriginal actors as David Gulpilil, as Nullah’s grandfather, often depicted in iconic postures that recall Gulpilil’s first appearances in Walkabout (Nicolas Roeg, 1971); David Ngoombujarra, memorable pawn in the legal game of Black and White (Craig Lahiff, 2002), as Drover’s offsider; and, very winning, young Walters as the child caught in the middle. Their performances make redundant the spelling out. It is a pity because it is the situation of Aboriginal life and beliefs in the society that has marginalized them that gives the film its chief claim to the epic in the Brechtian sense.

As suggested earlier, the love story and the mixed-race conflict are only two of the film’s narrative elements. As well, there is a drama about inheritance, the brittle Sarah determining to save Faraway Downs with the help of Drover. There is the Anglo-Australian theme, not merely sketched in the Sarah–Drover skirmishes, but also in the mixed attitudes to the arrival of an English aristocrat and in the Aussie bully trying to take over the English-owned station (and from whom had the English owner taken it over in the first place?). The threat of war brings of course a heightened tension to all the plot’s strands, without actually imbuing them with a coherence of purpose that would give shape to the film’s epic intentions. The attack on Darwin is brilliantly staged and shot, but its function as the plot’s deus ex machina is both oddly arbitrary and strangely muted.

One doesn’t want to sound grudging about so eagerly awaited a film event from a major Australian filmmaker, and there are certainly things to admire about Australia. Compared though with the way Luhrmann made riotous eclecticism work so enchantingly for him in the patent artificialities of Moulin Rouge!, I have to say that, for me, the eclecticism in narrative motifs, casting and music of the new film remains a collection of scattered ambitions and effects. The breath, as I said earlier, is often taken by the film’s physical grandeurs, but the heart is rarely stopped.

Endnotes

| 1 | Australia, production notes, p.3. |

|---|---|

| 2 | Brian McFarlane, ‘Groupings and Gropings in Australian Cinema: Adi Wimmer’s Australian Film Cultures, Identities, Texts’, Overland, no. 193, Summer 2008, pp.95–96. |

| 3 | Sylvan Barnet et al., A Dictionary of Literary Terms, Constable, London, 1964, p.60. |

| 4 | M.H. Abrams, A Glossary of Literary Terms, 4th edition, Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1981, p.52. |

| 5 | Jeffrey Richards, Hollywood’s Ancient Worlds, Continuum, London, 2008, p.1. |

| 6 | Australia, op. cit., p.5. |