As I work my way through each new edition of Metro, I see the contents grouped first into articles on Australian cinema and then into a focus on Asia. This suggests some sort of intellectual urgency or specificity of interest for Australians – a claim that Asian cinema ranks, or should rank, high on our cultural agenda. Given this auspicious occasion for Metro, it is appropriate to pause and examine that assumption.

The major pathway many Australians have taken to Asian cinema has been the fan route. Martial arts, anime and hero-gangster films have long led young moviegoers to seek out protagonists with big eyes and heroes who can kick their adversaries in the chest or mow down an army without reloading their automatic pistols. I remember the lights coming up after my first John Woo film and being amazed that all films were not like this. Suddenly, there were movies that moved, unfettered by restraint or considerations of good taste or pious moralism. There was a freedom here in which stylistic flourish and daring athleticism could find free rein.

The industrial effects of these films should not be sneezed at by Australians, either. The Madman distribution company grew out of Chinatown Video, a label set up to release VHS versions of Jackie Chan and Jet Li films. The business continues to be anchored on the demand for anime.

A second path to Asian cinema has been the arthouse, which, since the 1960s, has recognised a handful of major auteurs such as Akira Kurosawa and Satyajit Ray. Since 2000, I have followed Asian cinema through festivals around Australia but also in Hong Kong, Busan and Tokyo, reporting on them in the pages of Metro. Festivals not only group films so that you can grasp the general trends that are emerging, but also give you a reason to go places. While more and more people are content to have their movies come to them in their homes and on their tiny little devices, I am thankful that the pages of Metro remain open to those perverse enough to still want to go to movies – even when it involves a plane trip.

But festival films are also examples of casting off restraint. If Hong Kong’s Woo took up Sergei Eisenstein’s mantle in furthering the affective possibilities of montage, directors like Taiwan’s Hou Hsaio-hsien and Tsai Ming-liang have appeared at the other end of this spectrum, boldly exploring the potential of minimalism and long takes. Other major figures such as Hirokazu Koreeda, Jia Zhang-Ke and Apichatpong Weerasethakul have appeared in Japan, China and Thailand, respectively. While Japan has constituted one of the world’s great national cinemas for almost a century, other countries in East Asia have routinely shown a willingness to experiment that has been singularly lacking in this country. Asia has been marked by its embrace of the new. This seems fitting, given that there is nowhere in the world that has undergone such ferocious change in the last few decades as East Asia.

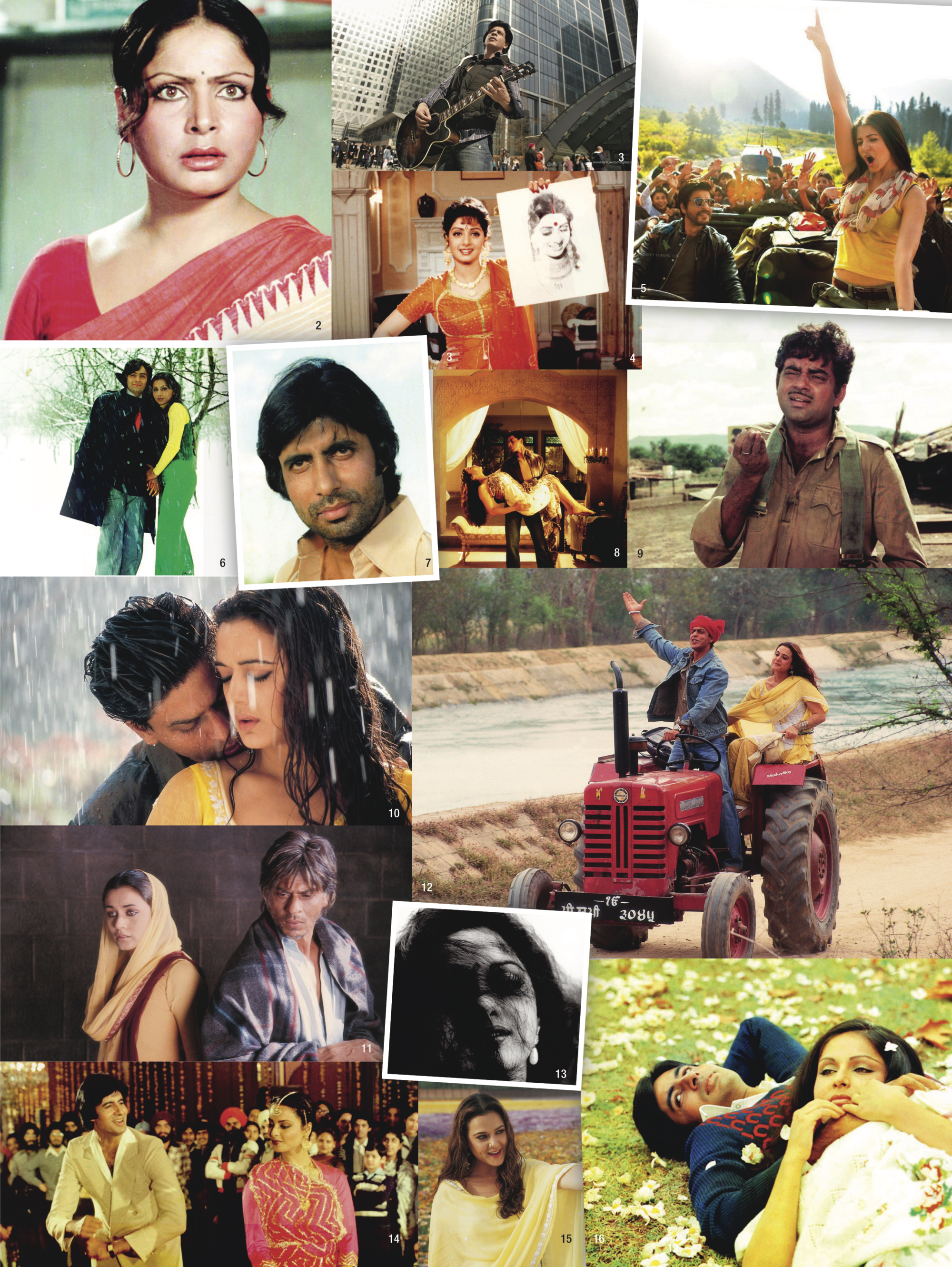

And, finally, there is a third pathway to Asian cinema that has only emerged strongly in Australia in the past few years: the surge in popular Asian cinema for diasporic and student audiences. As Motion Picture Distributors Association of Australia box-office figures show, Indian films of a variety of languages, along with Chinese and Korean films, now constitute fully one-third of all the films released commercially in this country. One-third! If we count among them co-productions such as The Meg (Jon Turteltaub, 2018) and Crazy Rich Asians (Jon M Chu, 2018), they account for almost 7 per cent of the Australian box office – significantly more than Australian films! To take up the rhetoric of Screen Australia: who is really telling our stories here?

As immigration from an array of countries increases, and as Australian tertiary education becomes more oriented towards a service provided for Asian students, our cinema-distribution landscape is being remade. Companies such as Mind Blowing Films, Southern Star, TangRen and China Lion release about five films each week, yet we rarely see any of them reviewed in the English-language press. These films don’t hang around in cinemas, and only a handful make it onto pay-TV or streaming services, but they are an undeniable part of Australian cinema; to pretend otherwise is to deny that the Asian communities of Australia are as Australian now as anyone else.

Certainly, challenges lie in the way of an integration of Asian films into Australian cinema. These are challenges that distributors, exhibitors, audiences and the press will need to face. And they are challenges that I will be keen to follow in Metro’s next 200 issues.