In September 2018, a forty-year-old Sydney man allegedly drove to the home of a thirteen-year-old boy and sexually assaulted him on the front lawn. The attacker and victim had reportedly connected on a hook-up app, exchanging photos and personal information before the teenager eventually ceased contact. News coverage suggested that the man, who was charged with sexual intercourse without consent, only stopped when the boy’s mother came running out of the house, having heard his screams.[1]See Mark Reddie & Jonathan Hair, ‘Sydney IT Manager Accused of Raping Schoolboy He Met on Grindr Is Granted Bail’, ABC News, 4 October 2018, <https://www.abc.net.au/news/2018-10-04/alleged-grindr-rapist-has-bail-continued/10337620>, accessed 28 October 2019. By contrast, Australia has also seen incidents in recent years of straight teenagers using gay-dating apps to lure same-sex-attracted older men to public places before robbing, threatening or assaulting them. In more than one instance, the young attackers viewed themselves as vigilantes, motivated by both homophobia and a desire to take action against, in the words of one assailant, ‘faggots and paedophiles’.[2]The quote is cited in Tim Clarke, ‘Perth Man Pleads Guilty to Five Brutal Bashings in Which He Lured Gay Men Through Dating App Grindr’, The West Australian, 17 November 2017, <https://thewest.com.au/news/wa/perth-man-pleads-guilty-to-five-brutal-bashings-in-which-he-lured-gay-men-through-dating-app-grindr-ng-b88661754z>; see also Megan Gorrey, ‘“I’m the Paedophile Hunter”: Canberra Teen Grindr Scammer Avoids More Jail Time’, The Canberra Times, 1 November 2017, <https://www.canberratimes.com.au/story/6026539/im-the-paedophile-hunter-canberra-teen-grindr-scammer-avoids-more-jail-time/>, both accessed 28 October 2019.

Matters of sex and age hold particular sensitivities in the queer community; many grow up hearing religious leaders claim, falsely and from the pulpit of hypocrisy, that homosexuality and paedophilia are inextricably linked. The recent international phenomenon that is Call Me by Your Name (Luca Guadagnino, 2017), which received criticism for its depiction of an ostensibly consensual relationship between a seventeen-year-old and a twenty-four-year-old,[3]See Jeffrey Bloomer, ‘What Should We Make of Call Me by Your Name’s Age-gap Relationship?’, Slate, 8 November 2017, <https://slate.com/human-interest/2017/11/the-ethics-of-call-me-by-your-names-age-gap-sexual-relationship-explored.html>, accessed 28 October 2019. is proof positive that this division is far from reconciled.

These complex concerns, which encompass ethical, sociocultural and political considerations, come to the fore in Samuel Van Grinsven’s confident, highly aestheticised debut feature Sequin in a Blue Room (2019). The micro-budget, Sydney-set film is very much a product of its time and place, addressing contemporary anxieties around the use of hook-up apps, connection in the digital age, queer teenage sexuality, drug use and more. It also pinpoints a highly specific concern of the newest generation of gender- and sexually diverse (GSD) youth, who are able to come of age – and come into their sexual selves – in an unprecedentedly tolerant, if not necessarily accepting, society, while also being offered queer-designated spaces to do so alongside their peers using the most uniting factor in their lives: the internet.

The film’s pared-down narrative follows sixteen-year-old Sequin (talented newcomer Conor Leach), who finds himself escaping the heteronormative misunderstandings and mendacity of his home and school life through increasingly adventurous, and eventually dangerous, experiences with older men orchestrated through a location-based hook-up app. His single father (Jeremy Lindsay Taylor) attempts to reach out to him, sensing the distance between them growing as Sequin’s secret life becomes more all-consuming. At the same time, Sequin’s classmate Tommy (Simon Croker) develops a crush on him, seeing the potential of a connection with a peer. Tommy’s wholesome, clumsy attraction to Sequin lends the otherwise-risky film an anodyne respectability, a conventionally romantic cloud hanging over its more transgressive notions. Nevertheless, Tommy’s presence enhances the tension between sexual maturity and identity as experienced by Sequin, who finds himself rapidly accumulating sexual experiences but struggling to properly process his sense of self.

If Sequin in a Blue Room is emblematic of anything, it is the past successes in, recent failures of and future possibilities for Australian queer film and TV. From the popular screen adaptation of Timothy Conigrave’s memoir Holding the Man (Neil Armfield, 2015) to similarly Sydney-set misfires like Teenage Kicks (Craig Boreham, 2016), Australian films about cisgender gay and bisexual men – easily the most frequently produced in the local queer sphere – have struggled to engage with queer aesthetics beyond the bare necessities demanded by their narratives. Other contemporary examples such as the features Downriver (Grant Scicluna, 2015) and Cut Snake (Tony Ayres, 2014), the 2016 miniseries Deep Water and the telemovie Riot (Jeffrey Walker, 2018) have been grounded – and perhaps curbed in their overarching queerness – by genre conventions, historicity or both. All of these works, as does much of our national cinema, exist in the considerable shadow of Australian film’s 1990s boom; however, far more than most comparative works, Sequin in a Blue Room feels as if it’s conversing with and a continuation of the likes of The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert (Stephan Elliott, 1994), Head On (Ana Kokkinos, 1998) and The Sum of Us (Kevin Dowling & Geoff Burton, 1994). The arguable temerity of what could be deemed Australia’s ‘Cinema of Marriage Equality’ often saw films burdened by the government-funded gloss of respectability that was at odds with the boldness of the New Queer Cinema boom that preceded them; with the societal issue of same-sex marriage largely settled and Australia’s anti-queer voices further changing targets to attack trans and gender-diverse people, Sequin in a Blue Room could herald a return to a queerer cinema – a new movement of films that enmesh queer creators, audiences, characters, aesthetics, politics and more in a dazzling, agitative rush.

Because of all this, and perhaps as a result of it being Van Grinsven’s graduate film from the Australian Film Television and Radio School’s Master of Arts Screen: Directing program, Sequin in a Blue Room feels less concerned with reflecting established norms and appealing to a typically homogeneous queer-film-festival audience than with establishing a distinct visual style and investigating ideas around identity and connection. As Van Grinsven explains in his director’s note, his intention was to turn his gaze ‘inward’ at the ‘community as it is today’, especially with regard to the centrality of digital technologies in the lives of queer youth, rather than presenting an image of it to the outside world:

I grew up as part of the first generation of young queer people to come of age with social media and hookup app communication. From Googling what it meant to be gay to joining ‘Gay Teen Chat Rooms’ and talking to strangers from around the world. From having to learn about gay sex from internet pornography to meeting my first boyfriend on Myspace. Every part of my coming of age as a queer person has been informed by the internet. The good and the bad.[4]Samuel Van Grinsven, ‘Directors Statement’, in Sequin in a Blue Room press kit, 2019, p. 2.

Sequin in a Blue Room is entangled in the questions of how the internet acts as a queer space, how it plays a role in self-construction and -acceptance, and how virtual space intersects with physical queer spaces. In 2007, sexuality scholar Vikki Fraser described social-networking platforms such as the now-defunct Mogenic as ‘the bar in the bedroom’: spaces where queer youth were able to tap into ‘those discourses previously restricted to the public queer space – the queer space of Oxford St, Darlinghurst, the bars, and beats’.[5]Vikki Fraser, ‘Gay Ghettos for the New Millennium: Oxford Street Meets Mogenic.com and the Question of Queer Space’, paper presented at Queer Space: Centres and Peripheries, University of Technology Sydney, Sydney, 2007, p. 3, archived at <https://web.archive.org/web/20091112035223/http://www.dab.uts.edu.au/conferences/queer_space/proceedings/online_fraser.pdf>, accessed 28 October 2019. The accessibility of the internet, and the individualised experience it offers, paved the way for the rise of hook-up apps in the queer community; within just a generation, the nature of that online space shifted dramatically. Whereas once-popular sites for GSD teenagers like Mogenic and The Gay Youth Corner – neither of which survived the shift into the smartphone age – offered what Fraser termed a ‘private space for public interaction, affirmation, exploration, visibility, and, for some, rejection’,[6]ibid., p. 3. today’s queer youth are increasingly capable of community-building in the open, both off- and online. Sequin’s excursions into the apartments of older strangers are, in a sense, means for him to explore both his sexuality and its sociocultural functions, as part of what researcher Sam Miles considers a contemporary ‘reconfiguration of sex at home as a new imbrication between domestic and public spheres rather than just an expression of, or retreat into, private space’.[7]Sam Miles, ‘Sex in the Digital City: Location-based Dating Apps and Queer Urban Life’, Gender, Place & Culture, vol. 24, no. 11, 2017, p. 1605, available at <https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/0966369X.2017.1340874>, accessed 28 October 2019.

Sequin in a Blue Room feels less concerned with reflecting established norms and appealing to a typically homogeneous queer-film-festival audience than with establishing a distinct visual style and investigating ideas around identity and connection.

Sequin’s path in the narrative reflects Van Grinsven’s fascination with the technologically facilitated fusion of the public and the private as well as the impact that locational apps have on how young people discover their sexuality. According to Fraser, ‘along with providing an initial point of contact with a “practice community”, [queer] spaces have implicit expectations of appropriate presentation underlying belonging and involvement’.[8]Fraser, op. cit., p. 2. Despite this, Sequin lies about his age, saying he is eighteen in order to use the app and infiltrate the spaces he does. Paradoxically, the restrictions of some newer online spaces can preclude younger queers from reaching out to one another as a result; in Sequin’s case, he instead finds himself drawn to ‘The Blue Room’, a private sex party he discovers through an app.

Sequin in a Blue Room treads a precarious line. It is at once encouraging and wary of its central character’s exploratory instincts. The film faces up to the contemporary reality of queer teen sexuality in a way few segments of today’s society – outside of local queer artists, LGBTQIA+ media and community organisations that focus on the sexual and mental health of GSD people – do. As exemplified by the aforementioned rape case, the standard response from authorities is to remind parents to discuss online safety with their children; this is alluded to in Van Grinsven’s film, which shows Sequin’s father to be patient, caring and empathetic. But, while discussion of online safety can contribute to young people’s harm avoidance,[9]See Marika Guggisberg, ‘Children Can Be Exposed to Sexual Predators Online, so How Can Parents Teach Them to Be Safe?’, The Conversation, 27 August 2019, <https://theconversation.com/children-can-be-exposed-to-sexual-predators-online-so-how-can-parents-teach-them-to-be-safe-120661>, accessed 11 October 2019. it may not offer them sufficient insights into their sexual inquisitiveness and impulses[10]See Karen L Blair & Sara MacKay, ‘When Straight Parents Are Lost on Queer Sex’, Psychology Today, 29 November 2018, <https://www.psychologytoday.com/ca/blog/inclusive-insight/201811/when-straight-parents-are-lost-queer-sex>, accessed 28 October 2019. – not to mention counterbalance their orientation having been historically erased or demonised for the sake of conservative respectability. The emotional damage wrought by the latter often reverberates well into adulthood,[11]See Jack Drescher, ‘The Closet: Psychological Issues of Being In and Coming Out’, Psychiatric Times, vol. 21, no. 12, 1 October 2004, <https://www.psychiatrictimes.com/cultural-psychiatry/closet-psychological-issues-being-and-coming-out>, accessed 11 October 2019. and can manifest in (sometimes risky) behaviour like that exhibited by Sequin.[12]See, for example, Darcel Rockett, ‘Gay and Bisexual Male Teens Use Adult Dating Apps to Find Sense of Community, Study Shows’, Chicago Tribune, 18 May 2018, <https://www.chicagotribune.com/lifestyles/ct-life-lgbtq-teen-grindr-use-20180517-story.html>, accessed 28 October 2019.

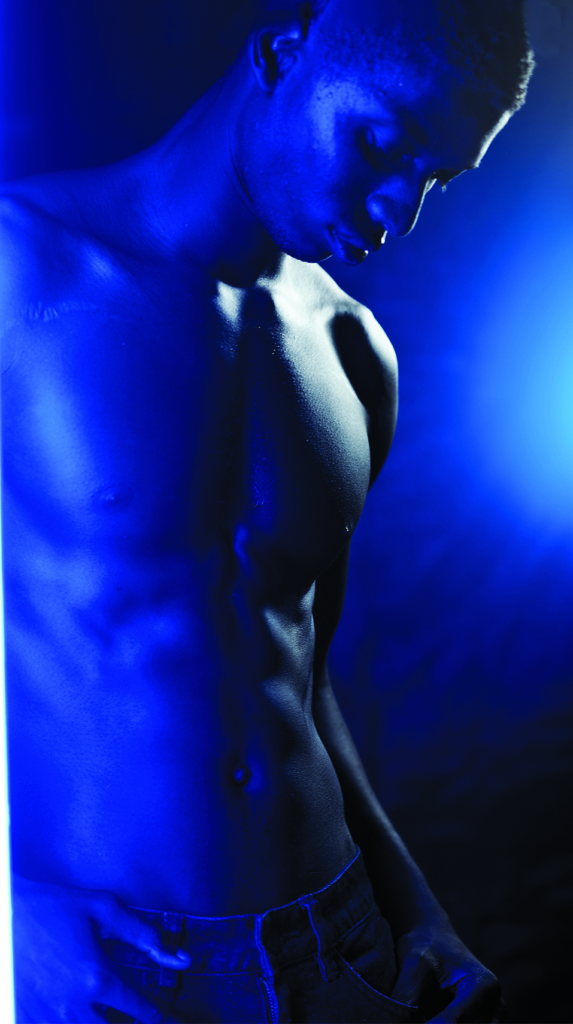

Given the extensive opportunities for self-exploration afforded by online spaces, Sequin’s curiosity about The Blue Room is no surprise. Beautifully realised by production designer Anna Gardiner and shot by cinematographer Jay Grant, the venue – a cavernous vacant level of a nondescript building – is draped in plastic sheeting and bathed in sensuous blue light. When combined with composer Brent Williams’ and sound designer Audrey Houssard’s work, the visual and aural space conjured feels indebted to queer-cinema pioneers like Gregg Araki and Gus Van Sant, cited as influences by Van Grinsven,[13]Frazer Bull-Clark, ‘Sequin in a Blue Room – an Interview with Samuel Van Grinsven’, 4:3, 14 June 2019, <https://fourthreefilm.com/2019/06/sequin-in-a-blue-room-an-interview-with-samuel-van-grinsven/>, accessed 28 October 2019. as well as to their descendants such as Xavier Dolan. Through Sequin’s eyes, we experience the excitement and trepidation that come from entering such a space – feelings that are only heightened as it is effectively where the first public (if still functionally private) voluntary expression of his sexuality is to take place.

There, Sequin encounters both past hook-up B (Ed Wightman), a much older man who has developed a fixation on him, as well as Edward (Samuel Barrie), a mysterious, handsome stranger over whom Sequin himself obsesses after he is told to meet outside the room. The ultimate results of both of these fixations are somewhat predictable. B’s unhealthy obsession soon intersects with Sequin’s real life in invasive, confronting ways. Sequin’s own desire for the ultimately unattainable Edward – who is of African descent – borders on fetishisation as a result of Sequin’s selfish presumptions and inexperience in discerning true intimacy from casual attraction. Though it is made clear that the headstrong, entitled Sequin lacks the literacy to understand the latter issue, it’s similarly unclear whether the film itself is acknowledging the uncomfortable, destructive nature of this one-sided dynamic.

The Edward plotline does reveal Sequin in a Blue Room’s attempt to mirror the ethnic diversity of real-world Sydney’s gay community, even if the film ultimately neglects to examine how the more complex facets of its supporting characters’ identities intersect with their sexualities, as well as with its protagonist’s own privileged identity as a young, thin, white, conventionally attractive cisgender gay male.[14]Another theme for which the film chooses mere representation over interrogation of broader social concerns is drug use. As with Teenage Kicks before it, Sequin in a Blue Room brushes up against the prevalence of crystal-methamphetamine use in the queer community – shown through Sequin’s encounter with the drug – but goes no further. Yet it has been found that, from 2014 to 2017, around 15 per cent of Australian queer men had recently taken the drug, with one in six reporting the acceptability of its use among friends and peers. See Shawn Clackett et al., Flux: Following Lives Undergoing Change – 2014–2017 Surveillance Report, The Kirby Institute, Sydney, 2018, pp. 40, 42, available at <https://kirby.unsw.edu.au/sites/default/files/kirby/report/Flux-2014-2017-Report.pdf>, accessed 28 October 2019. This is not to say that the film is unconcerned with these elements. Sequin’s ability to access highly sexualised, adult spaces, for example, is established as being partly a result of those characteristics. Similarly, the introduction of Virginia (Anthony Brandon Wong) as a somewhat objectified ‘fairy godmother’ figure, initially via fraught and illicit circumstances, further problematises Sequin in a Blue Room’s racially diverse casting, even in spite of the maternal warmth of Wong’s performance. The film’s non-white characters are marginally established beyond Sequin’s perception of them and provided thinly drawn inner lives that, if given more primacy, may have made for potent commentary on the contrast between the experiences of dominant queer individuals and queer folks from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds.

Sequin in a Blue Room treads a precarious line. It is at once encouraging and wary of its central character’s exploratory instincts. The film faces up to the contemporary reality of queer teen sexuality in a way few segments of today’s society do.

The existence of a diverse cast hints that Van Grinsven and co-writer Jory Anast are seeking to address the contradictions of a generation who are immersed in diversity, but are slow to examine it in a community wherein deep-seated racism and racial stereotyping run rife and reinforce entrenched, exclusionary social dynamics.[15]See, for example, Lungol Wekina, ‘My Race Is Not Your Fetish’, Tharunka, 15 February 2018, <https://tharunka.arc.unsw.edu.au/my-race-is-not-your-fetish/>, accessed 28 October 2019. But, whether it’s a result of limited scope or a tentativeness on the part of Van Grinsven and co. to speak ‘on behalf of’ queer people of colour in Australia, the film feels satisfied with offering uninterrogated visibility. Sequin in a Blue Room’s reluctance or resistance when it comes to mining the deeper significance of ‘diversity’ inhibits it from unearthing more varied, rarely examined sub-themes around identity and inequality. While, for example, we get to see Sequin’s response to B’s toxic behaviour, the absence of an actual encounter between Sequin and Edward outside The Blue Room – Sequin sees but a brief glimpse of his romantic interest’s home life after stalking him to his front door – illustrates the film too lightly brushing off Sequin’s own idée fixe as a myopic folly of youth rather than, perhaps, examining the more destructive element it could have been.

These elements are noticeable chiefly because the stylistic and narrative components of Sequin in a Blue Room are so well realised. Van Grinsven’s first film – appropriate for its academic background – feels like a thesis statement undergirding the evolution of Australian queer cinema. By exploring terrain that better aligns with the realities of today’s young viewers in a manner that also caters for the established local festival audience,[16]As attested to by Sequin in a Blue Room being awarded financial assistance from the Queer Screen Completion Fund in 2019 and subsequently winning the Audience Award for Best Feature at that year’s Sydney Film Festival. Van Grinsven presents both makers and moviegoers with the possibility of a bolder path forward for queer cinema.

While the film may continue to wrestle with the contentious line between examining and pathologising sexual adventurousness until its concluding moments, it feels appropriately reflective of major generational shifts within the queer community. Sequin in a Blue Room depicts how the constantly evolving societal contexts for sexual self-discovery cause major shifts in how young queer people’s identities are formed, performed and understood, and subtly challenges the nature of past, existing and as-yet-unformed spaces through which GSD youth can move beyond longstanding external limitations.

https://www.sequininablueroom.com

Endnotes

| 1 | See Mark Reddie & Jonathan Hair, ‘Sydney IT Manager Accused of Raping Schoolboy He Met on Grindr Is Granted Bail’, ABC News, 4 October 2018, <https://www.abc.net.au/news/2018-10-04/alleged-grindr-rapist-has-bail-continued/10337620>, accessed 28 October 2019. |

|---|---|

| 2 | The quote is cited in Tim Clarke, ‘Perth Man Pleads Guilty to Five Brutal Bashings in Which He Lured Gay Men Through Dating App Grindr’, The West Australian, 17 November 2017, <https://thewest.com.au/news/wa/perth-man-pleads-guilty-to-five-brutal-bashings-in-which-he-lured-gay-men-through-dating-app-grindr-ng-b88661754z>; see also Megan Gorrey, ‘“I’m the Paedophile Hunter”: Canberra Teen Grindr Scammer Avoids More Jail Time’, The Canberra Times, 1 November 2017, <https://www.canberratimes.com.au/story/6026539/im-the-paedophile-hunter-canberra-teen-grindr-scammer-avoids-more-jail-time/>, both accessed 28 October 2019. |

| 3 | See Jeffrey Bloomer, ‘What Should We Make of Call Me by Your Name’s Age-gap Relationship?’, Slate, 8 November 2017, <https://slate.com/human-interest/2017/11/the-ethics-of-call-me-by-your-names-age-gap-sexual-relationship-explored.html>, accessed 28 October 2019. |

| 4 | Samuel Van Grinsven, ‘Directors Statement’, in Sequin in a Blue Room press kit, 2019, p. 2. |

| 5 | Vikki Fraser, ‘Gay Ghettos for the New Millennium: Oxford Street Meets Mogenic.com and the Question of Queer Space’, paper presented at Queer Space: Centres and Peripheries, University of Technology Sydney, Sydney, 2007, p. 3, archived at <https://web.archive.org/web/20091112035223/http://www.dab.uts.edu.au/conferences/queer_space/proceedings/online_fraser.pdf>, accessed 28 October 2019. |

| 6 | ibid., p. 3. |

| 7 | Sam Miles, ‘Sex in the Digital City: Location-based Dating Apps and Queer Urban Life’, Gender, Place & Culture, vol. 24, no. 11, 2017, p. 1605, available at <https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/0966369X.2017.1340874>, accessed 28 October 2019. |

| 8 | Fraser, op. cit., p. 2. |

| 9 | See Marika Guggisberg, ‘Children Can Be Exposed to Sexual Predators Online, so How Can Parents Teach Them to Be Safe?’, The Conversation, 27 August 2019, <https://theconversation.com/children-can-be-exposed-to-sexual-predators-online-so-how-can-parents-teach-them-to-be-safe-120661>, accessed 11 October 2019. |

| 10 | See Karen L Blair & Sara MacKay, ‘When Straight Parents Are Lost on Queer Sex’, Psychology Today, 29 November 2018, <https://www.psychologytoday.com/ca/blog/inclusive-insight/201811/when-straight-parents-are-lost-queer-sex>, accessed 28 October 2019. |

| 11 | See Jack Drescher, ‘The Closet: Psychological Issues of Being In and Coming Out’, Psychiatric Times, vol. 21, no. 12, 1 October 2004, <https://www.psychiatrictimes.com/cultural-psychiatry/closet-psychological-issues-being-and-coming-out>, accessed 11 October 2019. |

| 12 | See, for example, Darcel Rockett, ‘Gay and Bisexual Male Teens Use Adult Dating Apps to Find Sense of Community, Study Shows’, Chicago Tribune, 18 May 2018, <https://www.chicagotribune.com/lifestyles/ct-life-lgbtq-teen-grindr-use-20180517-story.html>, accessed 28 October 2019. |

| 13 | Frazer Bull-Clark, ‘Sequin in a Blue Room – an Interview with Samuel Van Grinsven’, 4:3, 14 June 2019, <https://fourthreefilm.com/2019/06/sequin-in-a-blue-room-an-interview-with-samuel-van-grinsven/>, accessed 28 October 2019. |

| 14 | Another theme for which the film chooses mere representation over interrogation of broader social concerns is drug use. As with Teenage Kicks before it, Sequin in a Blue Room brushes up against the prevalence of crystal-methamphetamine use in the queer community – shown through Sequin’s encounter with the drug – but goes no further. Yet it has been found that, from 2014 to 2017, around 15 per cent of Australian queer men had recently taken the drug, with one in six reporting the acceptability of its use among friends and peers. See Shawn Clackett et al., Flux: Following Lives Undergoing Change – 2014–2017 Surveillance Report, The Kirby Institute, Sydney, 2018, pp. 40, 42, available at <https://kirby.unsw.edu.au/sites/default/files/kirby/report/Flux-2014-2017-Report.pdf>, accessed 28 October 2019. |

| 15 | See, for example, Lungol Wekina, ‘My Race Is Not Your Fetish’, Tharunka, 15 February 2018, <https://tharunka.arc.unsw.edu.au/my-race-is-not-your-fetish/>, accessed 28 October 2019. |

| 16 | As attested to by Sequin in a Blue Room being awarded financial assistance from the Queer Screen Completion Fund in 2019 and subsequently winning the Audience Award for Best Feature at that year’s Sydney Film Festival. |