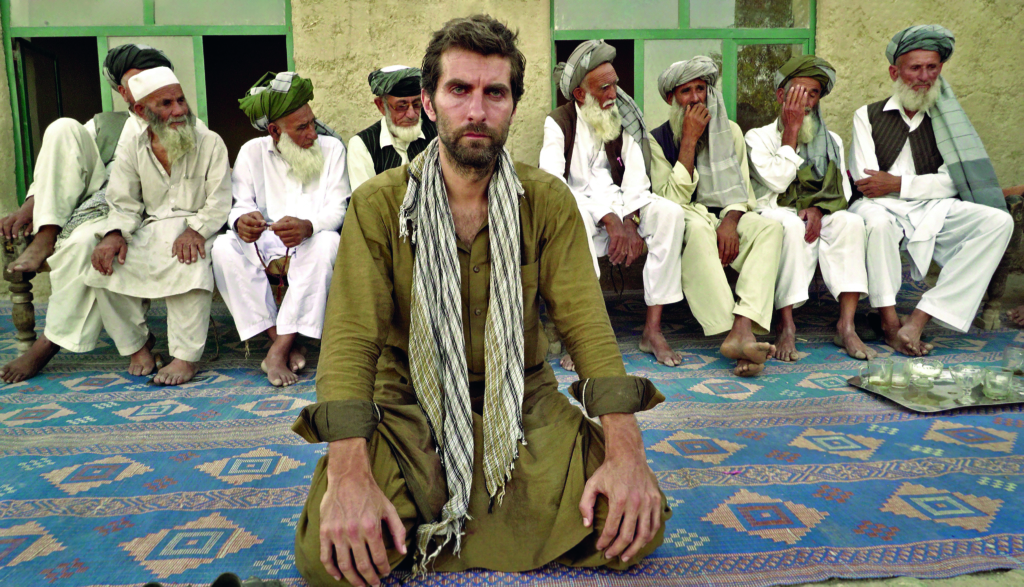

In Jirga (Benjamin Gilmour, 2018), an Australian undertakes a perilous journey to return to the site of an Afghan firefight from three years earlier. Mike (Sam Smith) makes the difficult trip not out of professional duty, however, but out of personal need. Haunted by his past deeds – specifically, the accidental killing of an unarmed civilian during an evening raid of a village – the ex-soldier is driven to atone for his actions. When he presents himself before the court of tribal elders that gives the feature its name, he risks his life, should the jirga deem an-eye-for-an-eye retribution the appropriate course of action.

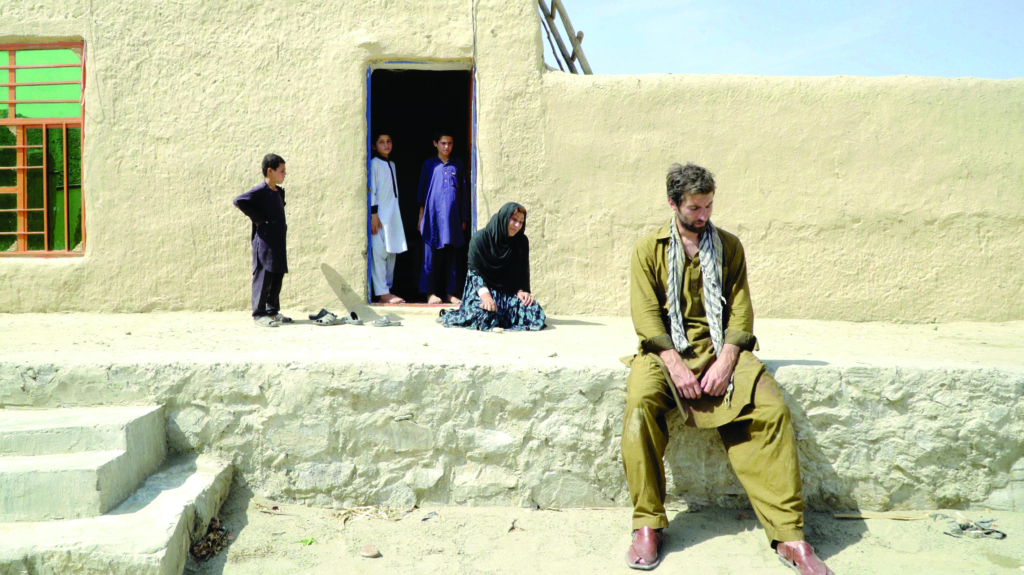

In charting Mike’s trek through often difficult, sometimes surprisingly beautiful Afghan terrain – from Kabul to Kandahar and beyond – as well as the emotional journey that he takes as he puts his fate at the mercy of others, the film also recounts his quest for redemption and restoration. But, more than that, the sensitive feature explores the idea of reclamation: of a man owning, rather than running from, his role in a horrific act, steadfastly facing the consequences and allowing everyone affected to move on.

Jirga marks the third feature effort in ten years by Gilmour, a paramedic-turned-filmmaker and an experienced world traveller. He has crafted a cinematic work that is the antithesis of stereotypical Hollywood war movies, depicting the conflict in the region more realistically and encouraging unity rather than animosity. It was also shot in secret in Afghanistan by Gilmour himself, travelling with Smith and no other crew, and boasts the air of authenticity that such a guerrilla approach brings. I speak to Gilmour about his inspiration for, intentions behind and experiences making this film.

Sarah Ward: What did you set out to achieve with Jirga?

Benjamin Gilmour: I think humans underestimate ourselves and underrate ourselves, and I think we’re actually capable of the extraordinary. We’re all capable of changing narratives in our own personal conflicts, since we are able to make extraordinary decisions that affect the lives of other people. With Jirga, I hope it demonstrates a wider strategy for peace in our own lives. Really, it’s a universal story that, I believe, is relatable because Mike – who has taken an action, albeit an accidental one, that has resulted in the death of another human being – could be any of us who have made mistakes in our lives and hurt others.

Even if you take that story out of the Afghan context, you still have this question around how far are we willing to go to make up for what we have done, to create some kind of healing, and not try and simply survive day to day with this enormous burden of guilt. It explores the themes of guilt and redemption that most human beings wrestle with to some degree.

‘People are really ready for it in this current world. They’re sick of that Donald Trump kind of rhetoric – the division and hatred, the ‘us and them’, the barriers and the borders and the walls … They’re craving films about reconciliation and how we can unite as human beings on this planet.’

—Benjamin Gilmour

People are really ready it for in this current world. They’re sick of that Donald Trump kind of rhetoric – the division and hatred, the ‘us and them’, the barriers and the borders and the walls […] People are frustrated with the resentment, hatred and xenophobia that come with that. They’re craving films about reconciliation and how we can unite as human beings on this planet.

You had travelled across sixty countries before you turned thirty, and worked as a paramedic both abroad and upon your return to Australia. Did you encounter many tales like Mike’s?

I’ve come across plenty of returned soldiers. When I first started as a paramedic in 1996, in those early days – and for most of the ten years of my career [after that] – the veterans that I would most commonly come across were in their eighties and nineties […] I would listen to their stories and their experiences of World War II. But then, in the mid 2000s (and I wasn’t the only paramedic to observe this), I more frequently started to come across damaged, broken soldiers from the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. Not all veterans suffer stuff in the same way, and some have done half-a-dozen tours [in] Afghanistan and seem to be unaffected. But there were certainly hundreds and hundreds of former soldiers out there who were suffering debilitating physical and mental injuries from those conflicts.

I was attending [to] those who had attempted suicides or had been taken to hospital for various physical or mental injuries […] It’s amazing how, if you’re a paramedic, people just open up to you straightaway. They’ve got their guard right down and it all gushes out. So there were stories that I was hearing that were very similar to the story of Mike.

The risk of killing civilians is high in Afghanistan because a lot of the raids are based on poor intelligence. They usually take place at night, when, even with night vision, visibility is poor. And the line between civilian and combatant in Afghanistan has always been blurry – [it’s] a tribal culture where, for thousands of years, tribesmen have owned weapons for the purposes of protecting their families. You’re putting Western soldiers into that environment, and it’s very frightening for an Afghan in that situation, seeing these scary, alien figures moving through their village at night with weapons and night-vision goggles on, in all these military outfits.

What invariably happens is that Afghans do what they’ve done for centuries and protect their families by firing. And you get people dying – ordinary people […] That man protecting his family in a small village in Afghanistan, is he a civilian or a combatant? To me, he’s a civilian who is armed. Most people would probably accept [that he’s] doing his best to protect his family.

There’s a vulnerability to Mike that makes him stand apart from other protagonists dealing with the impact of war. Do you see Jirga fitting in with or purposefully challenging the prevailing narrative in war films, particularly those made in the US?

There’s a distinction between the veteran in our film and some of the other soldiers in popular war films of recent years […] It’s pretty clear that [Mike is] a man who is living with guilt – and I imagine that his character is unable to function properly in society because of this burden – so it’s totally reasonable that he does have post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). But we really wanted the focus to be on his moral courage: the very clear and purposeful moral decision that he makes to buy a ticket as a civilian and return to Afghanistan, with the intention of finding the family of the man he killed. This is not a soldier who is disorientated, who is confused. He’s very clear about what he wants to do.

It’s probable that he has self-loathing about his actions, about what happened three years earlier [and] that he’s in denial about the risks. It’s not necessarily that he’s got a death wish, but the desire he has to repair the damage that he has caused is far greater than any care that he seems to have for his own safety […]

‘I’m really against the black-and-white, goodies-vs-baddies paradigm that has been espoused by Hollywood. It’s that narrative that we’re getting in everything from children’s animations to adult war films, and it’s so simplistic.’

—Benjamin Gilmour

So often, in war films, it’s frustrating. They frame the American – even an American soldier with PTSD – as the hero in a story against the Indians or the helpless, hopeless or brutal natives of whatever country the film is set in, whether it’s American Sniper [Clint Eastwood, 2014] in Iraq or others. I’m really against the black-and-white, goodies-vs-baddies paradigm that has been espoused by Hollywood. It’s that narrative that we’re getting in everything from children’s animations to adult war films, and it’s so simplistic. I don’t find it interesting at all, and I don’t find it realistic.

Jirga certainly gives a sense of what the distinctive landscape of Afghanistan looks like – a sense that is at odds with how other films portray the region. What were you trying to convey about the country, visually?

I love subverting expectations. Not in a way that’s fictitious, but in a way that’s realistic. You could apply that to the depiction of ordinary Afghans in Jirga. You could apply that to the depiction of the Taliban. And even the landscape – so, from a landscape point of view, the landscape is a character. We do have dry, dusty deserts in Jirga; there are those places in Afghanistan, and they’re very harsh environments. But there’s also valleys and provinces that could pass for the Swiss Alps that are full of fir trees and lush fields and beautiful rivers and fruit trees.

You may recall the segment in the film in Band-e Amir, on the swan boats. It is the most beautiful place I have ever been to in my life, and I had read about those lakes in old hippie traveller diaries because, originally, the film I wanted to make was about the hippie trail (which was an old overland journey that a lot of people took […] back in the 1960s and 1970s). During research for that particular film that I haven’t yet made – maybe one day – I read about this particular place. In 2013, I went on a reconnaissance trip to Afghanistan and visited it. I was just amazed by its beauty and this incongruous row of little, wistful, pastel-coloured swan pedal-boats left behind from Soviet times or even before.

I just love the opportunity in film to surprise the audience, and turn their stereotypes upside down and their expectations inside out.

You originally secured an investor for Jirga, cast Smith and planned to shoot in Pakistan, but then funding fell through. What challenges did that cause?

Venturing on to Afghanistan – the two of us, actor and director, with just a couple of phone numbers of locals that we’d been given – was a huge undertaking. It was really going out on a limb. I was very surprised that Sam agreed […] But I think we were in the mood. To return home and not explore the possibilities until the end would’ve had us always wondering how it may have turned out if we’d just had the guts to keep going.

When you’re in the moment, it’s really hard to see the positivity of changes like having your funding pulled, and sometimes it’s only revealed later. I realised later that this story was set in Afghanistan […] and, because I’m so passionate about authenticity, I needed to be true to authenticity across everything, including shooting the film where it was set. Audiences can smell artifice. They can sniff it out and have become very suspicious […] So it was a blessing that everything fell over in Pakistan. We got to shoot in Afghanistan, and we got all the naturalism and all the authenticity that came with doing that.

The fact that we had to shoot guerrilla-style added to the feeling of immediacy and rawness that the story demanded. If we’d had our full budget and we had proceeded with a professional cinematographer, it may have looked too slick – it may have looked like a perfume commercial. There were all these changes that, at the time, seemed to be nightmarish but ended up being good.

Also, without money, you improvise – and improvisation is creativity […] When you can’t fake things because you can’t afford to fake things, you can’t create sets and stitch fancy costumes and set things up. You’re reliant on whatever is there at the time […] When you can’t afford professional actors and you have to use non-actors whose lives are, in fact, very similar to the characters they are playing, what you end up with is this sense of reality.

Audiences who’ve been responding to Jirga so wonderfully have been commenting […] on that level of authenticity and reality that they’re experiencing while watching the film. Many are actually convinced that they’re watching a documentary until probably halfway through, and that’s exactly what we were trying to achieve.

Were there moments during shooting that you thought were too risky?

There were doubts all the time. But certainly, from my point of view, I had [put] those doubts out of my mind [so as to] just get on with the task. There’s also a certain point where you’re just in the thick of it, and there’s a problem with giving up when you’re halfway through a drama shoot because you know it would render everything you’ve done up to that stage pointless – you need it all done together. So the more you shoot, the more you realise that there’s no turning back.

That level of pressure and the war conditions that we were sometimes shooting in [are] the same mysterious pressure that people in crisis find brings out the best in humans. It certainly brings out the best in me. I feel that I’m at my best under that level of pressure and tension. In my work as a humanitarian in various disaster zones and as a paramedic encountering the occasional major incident, what you find in those crisis situations is that people are capable of the most extraordinary things and can draw on this powerful reserve.