In early 1915, international swimming champion Duke Kahanamoku held exhibitions at Sydney beaches to demonstrate the ancient Hawaiian sport of surfing to hundreds of onlookers.[1]See Russell Jackson, ‘Who Was Australia’s First Surfer? A Century-old Tale of Sailors, Spectators and a Duke’, The Guardian, 16 March 2017, <www.theguardian.com/sport/2017/mar/16/who-was-australias-first-surfer-a-century-old-tale-of-sailors-spectators-and-a-duke>, accessed 14 March 2021. When fifteen-year-old Isabel Letham volunteered to join him for a tandem ride, she cemented a place in history as one of the first Australians to ride Hawaiian style. While her exact place in the surfing timeline is debated – for a long time, she was considered the first ever Australian surfer, but this has since been disproven – we know that Letham went on to teach countless Californians and Sydneysiders how to swim, building a career around the water despite gender-based discrimination.[2]ibid.

Letham isn’t mentioned in Girls Can’t Surf (2021), Christopher Nelius’ documentary about female pro surfers in the 1980s and 1990s, but traces of her story echo throughout. Through archival footage and testimony from some of the biggest names of the era, the film presents a group of women who overcame intense hostility and discrimination to create a powerful surfing legacy.

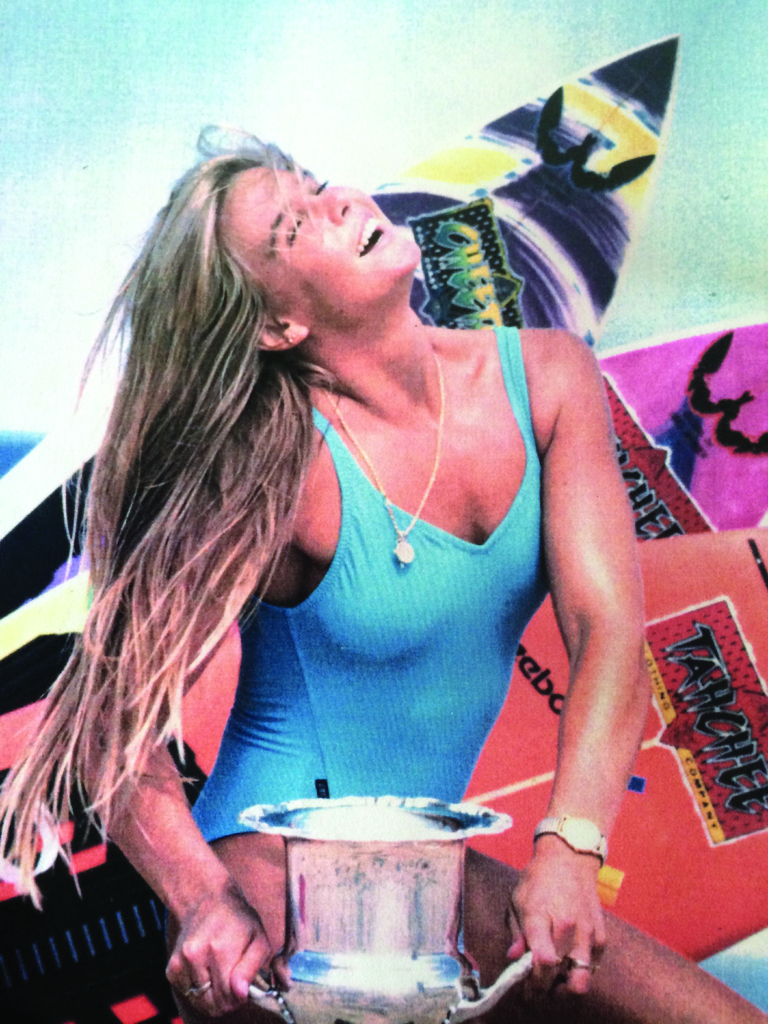

The hostility was at times brutal. New South Wales surfer Pauline Menczer, who entered the pro circuit in the 1980s, describes once being kicked in the stomach by a local male surfer. ‘They would yell out, “What are you doing out here? Girls should be on the beach! Get out!”’ she recalls in the documentary. West Australian surfer Jodie Cooper had a similar experience: in 1989, she was punched in the face by a male pro surfer because he didn’t want to share the waves.[3]See Reggae Elliss, ‘“Everyone Saw It but They Didn’t Want to Get Smacked in the Head”’, Surfing World, 14 June 2017, <https://surfingworld.com.au/jodie-cooper/>, accessed 21 April 2021. Resistance came at every level for these surfers, from aggression in the water to microaggressions in the contests. Being supplied with high-cut competition bathing suits might sound relatively innocuous until you learn that the discomfort and impracticality of the garments prohibited performance and, in at least one case, according to the documentary, led to injury.

The most obvious challenge for these women, however, was the pervasive financial discrimination they faced. Women on the pro circuit routinely earned a fraction of what their male counterparts were awarded: in 1991, the total prize money awarded to men was US$1.7 million, while for women it was just US$165,000.[4]‘Equal Pay, Equal Waves: Why Their Story Had to Be Told’, in Madman Films, Girls Can’t Surf production notes, 2020, p. 10. The disparity across all contests meant that just being able to compete was an enormous challenge. Menczer describes sleeping on the floors of international tournament hubs, and trying to sell marked-up American jeans in France just to pay her way.

The documentary convincingly uses the surfers’ push for better remuneration as its core narrative thread. Tracing the key events on this path in a roughly chronological order creates a powerfully coherent story that allows for important parallel issues to be touched on. It also means that the film’s concluding revelation – that competition prize money finally reached gender parity in 2019[5]See Saxon Baird, ‘Why Female Surfers Are Finally Getting Paid Like Their Male Peers’, The Atlantic, 14 April 2019, <https://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2019/04/how-female-surfers-won-pay-equity-fight/587065/>, accessed 21 April 2021. – is immensely satisfying.

Navigating the rip-tide

Girls Can’t Surf doesn’t set out to tell a complete history of women’s surfing, and it’s a better film for it. But this approach also inevitably raises questions, and the biggest one for me was the apparent lack of logical progression outside the events of the film. Which is to say: if Letham was surfing in 1915, albeit with some hurdles, how is it possible that such little progress was made over the seven decades between then and the events of the film? My confusion increased when I recalled that Sandra Dee happily surfed her way across cinema screens in 1959[6]As the titular protagonist of Gidget (Paul Wendkos, 1959). – evidently, women have been surfing all along. So how did things get so bad by the 1980s?

Researcher Leanne Stedman offers some insight into this paradox in her 1997 essay on the role of women in surfing,[7]Leanne Stedman, ‘From Gidget to Gonad Man: Surfers, Feminists and Postmodernisation’, The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Sociology, vol. 33, no. 1, 1997, pp. 75–90. arguing that the scene as a whole experienced a drastic change in the 1970s and 1980s as mainstream culture coopted its symbols, undermining the subculture’s ability to express a distinct collective identity. With the commodification of what had traditionally been a ‘“free” surfing lifestyle’,[8]ibid., p. 80. the subculture underwent what Stedman calls a ‘masculinisation’, which occurred alongside (and no doubt also contributed to) a ‘progressive exclusion of women’.[9]ibid., p. 81. When faced with the reality that surfing had crossed over into the mainstream, she argues, the subculture redefined itself to once again oppose dominant ideas – in this case, a ‘“mainstream” tolerance of feminists’.[10]ibid., p. 82.

Watching the events of the film play out with Stedman’s theory in mind lends weight to the oppression these women were facing. I don’t mean to imply that, without this knowledge, their plight is any less believable – the documentary paints an utterly convincing picture of a deeply misogynistic landscape – but that understanding the driving forces behind that sexism makes it look a lot less like passive resistance (an attitude of ‘we just want things to stay the way they are’), and a lot more like an active, sinister intention.

Ultimately, that intention was to put women firmly in their place, and to ensure that that place was far from the waves. That aim consistently emerges from the varied stories of oppression that the pro surfers tell throughout Girls Can’t Surf. The violence told them to stay out of the water; bathing suits designed primarily for sex appeal told them to remain objects rather than subjects; the financial barriers told them their talent had no value. The singular role that emerged for women in this subculture was one of passive objectification.

The women in Girls Can’t Surf recount how difficult it was to get sponsorship or significant media attention. According to Cooper, the media wanted them to ‘surf like a man and look like a woman’. She recalls approaching the major surfing magazines to try to get coverage, with little success:

They didn’t believe in it […] The only way you could get an article is once every two years when a magazine would go, ‘It’s about time we dust off the old girls story,’ and they’d do a story about the whole group.

South African–Australian surfer Wendy Botha, who won four world titles, describes getting press coverage as ‘sheer luck’. In 1992, she tried to work within the narrow parameters set by the media (and the surfing subculture) by posing nude for Australian Playboy. The move was unpopular with her peers. Elsewhere, Australian surfer Pam Burridge recalls being told that she needed to lose weight in order to gain more attention for women’s surfing; she went on to develop an eating disorder.

When Cooper was outed as a lesbian after fellow contestants found her journal on tour, she was dropped by her sponsor; she sums up their attitude at the time as, ‘She’s just another fucking dyke.’ Burridge, who won the world title in 1990, recalls making attempts to prove her heterosexuality – including acting as if she was okay with unwanted sexual advances from industry men – such was the fear of being marked a lesbian. And Menczer admits she still finds it hard to be open about being gay all these years later, having hidden it for so long.

Catching the curl

The Ocean Pacific Pro, which was held annually at Huntington Beach in California, was the biggest surfing competition in the mainland United States. In the early 1980s, though, its annual bikini contest was almost as famous, drawing hordes of onlookers who had little interest in surfing. According to sports scholar Douglas Booth, writing in the Journal of Sport History in 2001, Cooper ‘regularly criticized the [Association of Surfing Pros] in the 1980s for employing bikini-clad women to “decorate” the podiums during victory ceremonies’.[11]Douglas Booth, ‘From Bikinis to Boardshorts: Wahines and the Paradoxes of Surfing Culture’, Journal of Sport History, vol. 28, no. 1, Spring 2001, p. 9.

Stedman outlines how images of women in surfing magazines changed dramatically throughout the 1980s and 1990s, reflecting this shift towards explicit objectification. Through photographic techniques, she writes, the women in the magazine pages were prevented from ‘also acting as subject by returning the gaze of the (assumed male) viewer’. Whereas it was common to see images of women returning the gaze throughout the 1970s, Stedman argues, by the mid 1990s ‘the vast majority of pictures of women on the beach [were being] taken from behind, often from a distance using a zoom lens’.[12]Stedman, op. cit., pp. 83–4.

The insidious insistence that women in surfing culture be thin, conventionally attractive (usually blonde), sexualised/fuckable and devoted to worshipping the men can be seen in other cultural artefacts from the era, notably Puberty Blues. Both the 1979 novel, written by Gabrielle Carey and Kathy Lette, and Bruce Beresford’s 1981 film adaptation depict a culture in which the girls are relegated to the sand, keenly watching their surfing beaus on the waves and eagerly waiting to provide them with snacks, sex and adoration.

For Carey and Lette, who based the book on their own experiences and wrote it when they were still teenagers, their place in their local surfing community was abundantly clear.[13]See Hilary McPhee, Other People’s Words, Pan Macmillan, Sydney, Australia, pp. 152–4. The novel adds gravitas to Stedman’s research and the testimonies in Girls Can’t Surf: it is clear that, in many cases, male surfers banded together to create an exclusionary fraternity based on aggressive heterosexuality – the representation of the sexual entitlement of Puberty Blues’ male characters is particularly harrowing – and misogyny. The climax of the book sees the two young protagonists upend the social order and paddle out into the waves themselves. This small but powerful final triumph mirrors the pro surfers’ climactic achievement of pay parity at the end of Girls Can’t Surf. But while the documentary’s narrative might prioritise equal pay, questions around the capability of women surfers fuel one of its most potent topics.

Indeed, it’s right there in the title. Many of the women interviewed recall interactions with people who doubted their abilities, and archival footage of sceptical commentary reinforces this general belief; Australian pro surfer Nat Young found it acceptable to say that ‘the top surfer from any beach could beat any woman that [he had] ever seen’.[14]Nat Young, quoted in ‘Equal Pay, Equal Waves: Why Their Story Had to Be Told’, op. cit., p. 8. Research on women’s surfing supports the prevalence of such attitudes. Booth notes that ‘male surfers considered physical prowess a masculine trait and they deemed women comparatively frail, delicate, passive, and neurotic’.[15]Booth, op. cit., p. 6. Nelius’ documentary goes deeper on this point by offering a systemic foundation for this belief, at least in the 1980s and 1990s: during pro tournaments, the women would be sent out to surf when the conditions were deemed too poor for the men. This tactic was so prevalent that it pushed the women competing to breaking point in 1999, when organisers at the South African Jeffreys Bay contest tried to send them out to ride waves that were nearly non-existent. Instead, the female contestants sat on the shore and refused to compete. The precedent set by this action inspired other surfers to take a stand, ensuring that women would henceforth be able to surf great waves during competitions.[16]‘Equal Pay, Equal Waves: Why Their Story Had to Be Told’, op. cit., p. 10. Finally, the world could see these elite athletes at their best.

With this information, we can begin to understand that the question of whether women can adequately perform in a sport that has traditionally been dominated by men isn’t simply a matter of talent. The point is a vital one, reverberating through countless arguments over the perceived talent and value of women in other sports; ongoing debates about the AFL Women’s competition – with the lack of pathways historically offered to young players impacting performance standards – come to mind.[17]See, for example, Jade Haycraft, ‘Mark! Kick! Tackle! The Reality of Fast-tracking Women into Elite AFL’, The Conversation, 2 February 2018, <https://theconversation.com/mark-kick-tackle-the-reality-of-fast-tracking-women-into-elite-afl-91007>, accessed 12 April 2021.

It’s this point that elevates Girls Can’t Surf from a great documentary to an urgent one. As a standalone film, it hits every note with its powerful story of underdogs rising to triumph against the odds, its rapid pace that takes the viewer from one exciting anecdote to the next and its vibrant characters. As a piece of sporting history that shows the path women athletes took to achieve something as rare as equal pay, however, it provides an instructional example as well as a necessary beacon of hope for all the sports that are yet to reach that milestone. This urgency is compounded when we consider the historical context outside of the film, which reminds us that progress can easily slip backwards. Achievements are hard won; vigilance is essential. These are lessons that we still desperately need, both within and beyond sporting institutions – and Girls Can’t Surf is a mighty case study.

Endnotes

| 1 | See Russell Jackson, ‘Who Was Australia’s First Surfer? A Century-old Tale of Sailors, Spectators and a Duke’, The Guardian, 16 March 2017, <www.theguardian.com/sport/2017/mar/16/who-was-australias-first-surfer-a-century-old-tale-of-sailors-spectators-and-a-duke>, accessed 14 March 2021. |

|---|---|

| 2 | ibid. |

| 3 | See Reggae Elliss, ‘“Everyone Saw It but They Didn’t Want to Get Smacked in the Head”’, Surfing World, 14 June 2017, <https://surfingworld.com.au/jodie-cooper/>, accessed 21 April 2021. |

| 4 | ‘Equal Pay, Equal Waves: Why Their Story Had to Be Told’, in Madman Films, Girls Can’t Surf production notes, 2020, p. 10. |

| 5 | See Saxon Baird, ‘Why Female Surfers Are Finally Getting Paid Like Their Male Peers’, The Atlantic, 14 April 2019, <https://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2019/04/how-female-surfers-won-pay-equity-fight/587065/>, accessed 21 April 2021. |

| 6 | As the titular protagonist of Gidget (Paul Wendkos, 1959). |

| 7 | Leanne Stedman, ‘From Gidget to Gonad Man: Surfers, Feminists and Postmodernisation’, The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Sociology, vol. 33, no. 1, 1997, pp. 75–90. |

| 8 | ibid., p. 80. |

| 9 | ibid., p. 81. |

| 10 | ibid., p. 82. |

| 11 | Douglas Booth, ‘From Bikinis to Boardshorts: Wahines and the Paradoxes of Surfing Culture’, Journal of Sport History, vol. 28, no. 1, Spring 2001, p. 9. |

| 12 | Stedman, op. cit., pp. 83–4. |

| 13 | See Hilary McPhee, Other People’s Words, Pan Macmillan, Sydney, Australia, pp. 152–4. |

| 14 | Nat Young, quoted in ‘Equal Pay, Equal Waves: Why Their Story Had to Be Told’, op. cit., p. 8. |

| 15 | Booth, op. cit., p. 6. |

| 16 | ‘Equal Pay, Equal Waves: Why Their Story Had to Be Told’, op. cit., p. 10. |

| 17 | See, for example, Jade Haycraft, ‘Mark! Kick! Tackle! The Reality of Fast-tracking Women into Elite AFL’, The Conversation, 2 February 2018, <https://theconversation.com/mark-kick-tackle-the-reality-of-fast-tracking-women-into-elite-afl-91007>, accessed 12 April 2021. |