Cinema and surveillance: the connection is far too direct to be called a metaphor. What is the purpose of a camera if not to capture the images of those who pass in front of the lens, whether or not they realise they’re being monitored? In one sense, a model of total surveillance is supplied by any ordinary fictional narrative film; within the limitations imposed by censorship, the camera is able to follow the characters wherever they go, even or especially in their most private, intimate moments. This, however, creates a curious paradox: any quasi-realist film that foregrounds the theme of surveillance within the narrative also tends to emphasise the limits of surveillance, since no technology in the real world has the power and freedom of a camera-eye moving through a fiction.

The point has not been lost on the New Zealand–born, Australian-based filmmaker Jonathan Ogilvie, who in 2017 completed a PhD on what he calls ‘cineveillant’ films, a coinage referring to ‘films that incorporate the tropes of surveillance in both form and narrative’.[1]Jonathan Ogilvie, ‘From Rainy Soho to Sunny Kings Cross: Remapping and Contemporizing Joseph Conrad’s The Secret Agent’, in Casie Hermansson & Janet Zepernick (eds), Where Is Adaptation? Mapping Cultures, Texts, and Contexts, John Benjamins Publishing Company, Amsterdam & Philadelphia, 2018, p. 324. One part of Ogilvie’s thesis consisted of the screenplay for his own contribution to the genre: the since-completed feature Lone Wolf (2021), originally set in Sydney but ultimately relocated to the inner north of Melbourne,[2]ibid. which premiered at this year’s International Film Festival Rotterdam. The formal conceit of Lone Wolf – an ambiguous, unhelpfully generic title, which could be applied to several characters – is that the main narrative has been pieced together from material captured by cameras within the fiction: primarily CCTV footage, but also records of Skype calls and videos shot on smartphones.

In practice, the effect is less austere than it sounds, since Lone Wolf is also a kind of pulp fiction, and Ogilvie allows himself a certain leeway within his self-imposed framework. For all the shots that peer down on the characters from restrictive high angles, individual scenes play out just as legibly as they would in a conventional drama, and the dialogue is no harder to make out. Nor does the technique evoke an Orwellian nightmare in which there is no escape from the camera’s oppressive gaze; in a sense, almost the opposite seems to be the case. By restricting himself to events that could semi-plausibly have been recorded, Ogilvie creates a piecemeal, abstract cinematic universe distinct from our own – and thus, as a low-budget filmmaker, supplies himself with an alibi for the fact that sections of the story are not shown on screen.

By restricting himself to events that could semi-plausibly have been recorded, Ogilvie creates a piecemeal, abstract cinematic universe distinct from our own.

There is another paradox lurking in Lone Wolf. This is a political thriller set in present-day Australia, tackling the highly topical subject of terrorism and the measures taken to prevent it. But it’s also an adaptation of a classic work of literature, Joseph Conrad’s The Secret Agent – first published in 1907, when, technologically, at least, surveillance was a far cry from what it is now. By Ogilvie’s account, his interest in Conrad’s novel was above all formal, stemming from the hunch that his ‘cineveillant’ interests could readily be explored through a narrative where the characters are ‘constantly under the scrutiny of the London Police’. But as he also acknowledges, a degree of social commentary is inherent in the updating process, which requires some consideration of how modern Australia resembles Conrad’s London – along with how it doesn’t.[3]ibid., pp. 324–6.

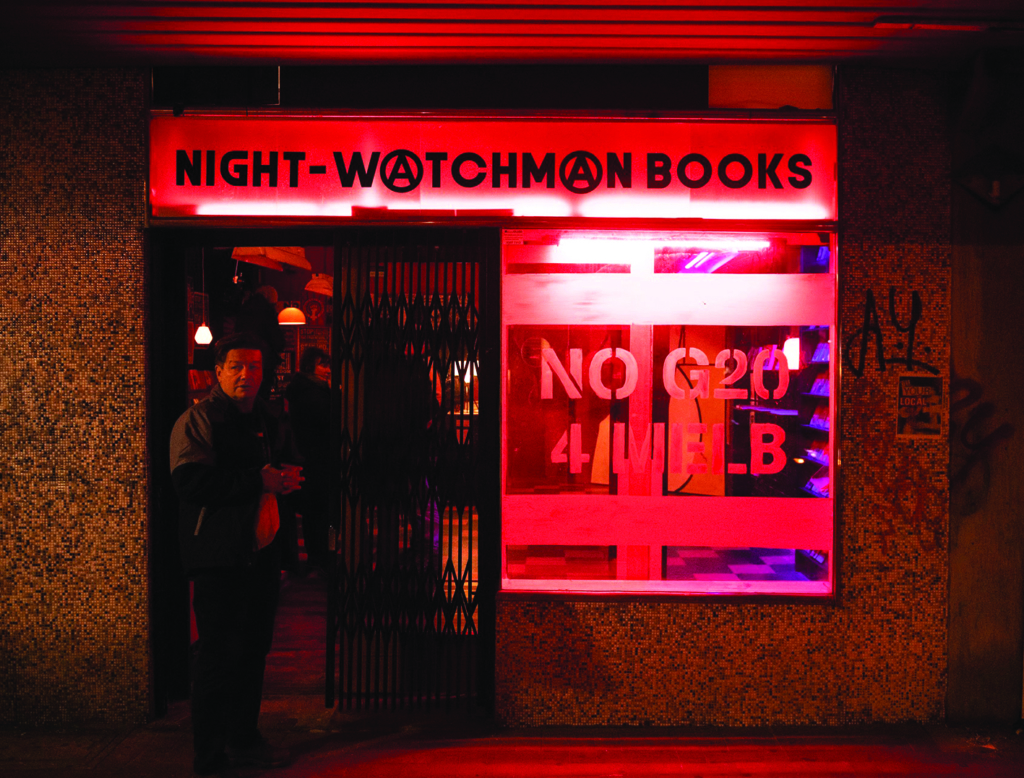

Terrorist attacks were certainly not unknown in Conrad’s day, even if the term ‘terrorism’ was not yet in wide use; as Conrad explains in his preface to the novel, its plot was inspired by an incident in 1894 in which the Royal Observatory in Greenwich was targeted by an anarchist bomber.[4]Joseph Conrad, ‘Author’s Preface’, The Secret Agent: A Simple Tale, Vintage Books, London, 2020 [1907], pp. xxi–xxii. From this arose the imagined character of Adolf Verloc (understandably renamed ‘Conrad Verloc’ in Lone Wolf), a seedy supposed anarchist who operates a run-down pornographic bookshop in a London backstreet, a cover for his mostly ineffectual plotting. This in turn masks his real work as an informer in the pay of the British government, who use him to stage an ‘outrage’ that will justify a crackdown on radical groups.

While Conrad’s portrayal of Verloc and his fellow anarchists is heavily ironic, his view of the forces of law and order is hardly less so; as he spells out in the book’s preface, he had no desire to ‘legitimize’ either side.[5]ibid., p. xxv. But The Secret Agent is not solely, or perhaps primarily, a political novel – Ogilvie aptly describes it as a tale of ‘the domestic gone rogue’,[6]Ogilvie, op. cit., p. 324. a theme personified by Verloc’s younger wife, Winnie, whose loyalty to her husband stems partly from the support he provides for her mentally disabled younger brother, Stevie. The book culminates in Stevie’s accidental death when he’s used as a pawn in a bomb plot; the anguished Winnie in turn kills her husband and then attempts to flee, before succumbing to despair and drowning herself on the way to France.

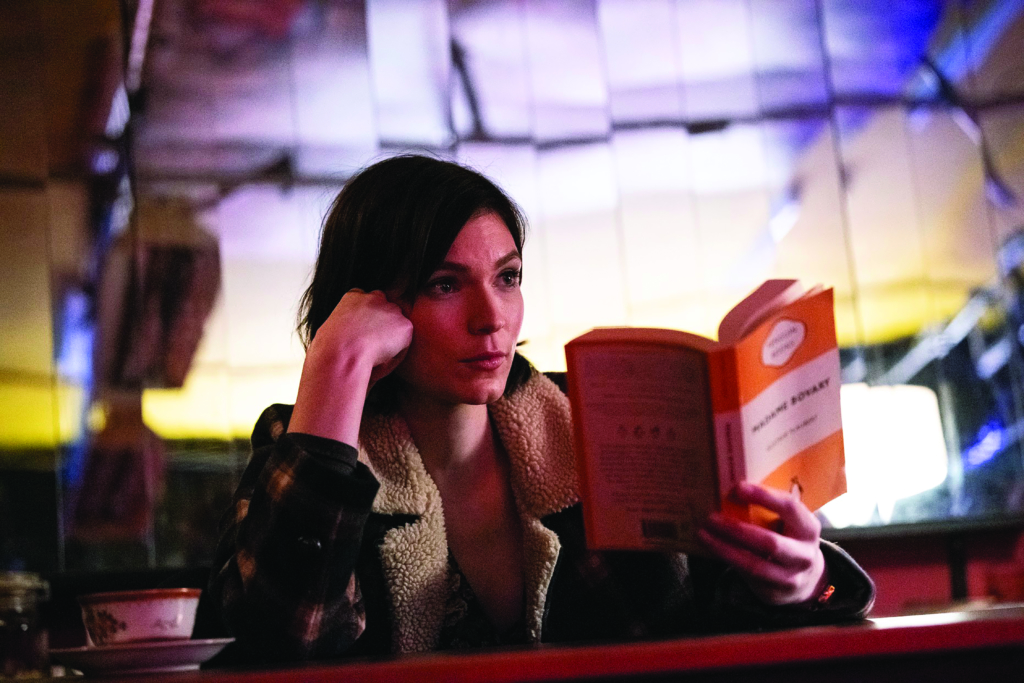

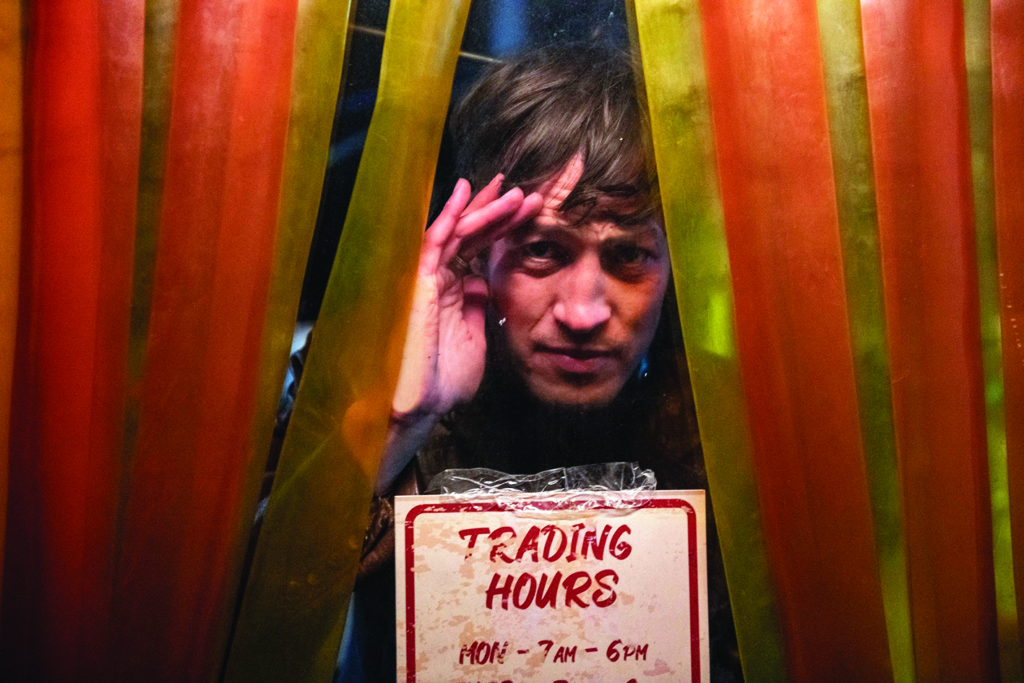

One of the striking things about Lone Wolf is how closely Ogilvie manages to follow this grim plot, which in modern dress retains a superficial credibility, even if the characters tend to be far less vivid than Conrad’s literary gallery of grotesques. Verloc’s mainly deserted adult bookshop, for instance, could conceivably still exist in the backstreets of Melbourne’s inner-north suburb of Brunswick – and the stolid Verloc (Josh McConville) himself is recognisably the antihero of the book, even if he’s morphed into a former musician whose look is half bruiser, half hipster. In the twenty-first century, the devotion of his girlfriend Winnie (Tilda Cobham-Hervey) is a little harder to fathom – though as with her equivalent in the novel, it’s clear that she’s motivated partly by concern for her brother Stevie (Chris Bunton), who has Down syndrome in this version of the story.

One of the striking things about Lone Wolf is how closely Ogilvie manages to follow Conrad’s grim plot, which in modern dress retains a superficial credibility, even if the characters tend to be far less vivid.

Of Ogilvie’s departures from the source material, two are especially significant. The first is the film’s ending, which allows Winnie an improbable second chance. The second is a new framing story: the footage that comprises the main part of the film is presented as an audiovisual dossier compiled by the police sergeant Kylie Heat (Diana Glenn), drawing primarily on footage from cameras she has secretly installed in Verloc’s shop (which is also his home). ‘I’ve shuffled some events and fast-forwarded to heighten the drama,’ she promises her corrupt superiors, the toadying Assistant Commissioner (Stephen Curry) and the villainous Minister of Justice (very broadly played by Hugo Weaving, sporting the kind of beard favoured by few Australian politicians since Barry Jones).

There is a sort of weary crudity to this portion of the film, which we are evidently not meant to take too seriously. All the same, the effect is to soften Conrad’s disillusioned vision into a more audience-friendly brand of melodrama: Heat gradually emerges as a heroine, whereas nothing of the kind could be said of her dogged but unsympathetic male equivalent in the book. She might also be considered some kind of stand-in for Ogilvie, since within the fiction she’s the primary author of the film we’re watching; while she maintains she didn’t examine the footage recorded by the security cameras till after the fact, a couple of anomalous zooms imply that an unseen witness is at least occasionally monitoring events as they occur.

That said, Heat is not the only character in Lone Wolf with a filmmaking bent. Another is Stevie, envisaged as a David Attenborough fan who uses his smartphone to shoot his own ‘nature documentaries’ about the strange behaviour of human beings. This is another not-exactly-successful storytelling device – not just because Stevie’s faux-naif commentary tends to be knowing to a fault, but because it’s less than fully clear how Heat winds up with the footage after Stevie is killed by a bomb he unwittingly delivers to Fitzroy Gardens, for what Verloc intends as a ‘victimless atrocity’.

Plot holes aside, Stevie’s death offers yet another variation on the theme of surveillance: when he disappears off screen during the lead-up to the explosion, any viewer will fear the worst; although Winnie, who believes he’s on a supervised fishing trip, doesn’t initially fret when he fails to answer her calls. What this brings home is that Lone Wolf is not precisely an anti-surveillance film – the vulnerable Stevie genuinely requires constant monitoring for the sake of his own safety. This is clear from other angles as well: it’s Heat’s surveillance of Verloc that enables her final, triumphant take-down of the minister, which ironically appears to seal the fate of his mooted anti-privacy laws.

In restricting the film to a certain number of camera angles and locations, Ogilvie turns it into a game played with the seen and unseen, what can be shown and what cannot.

As this suggests, the political project of Lone Wolf remains ambiguous: Ogilvie is scarcely interested in exploring the loosely anarchist philosophies espoused by Verloc and his mates, though we’re allowed to sympathise with Winnie and Stevie’s shared commitment to animal rights. Nor, on the other hand, does the film quite accord with Ogilvie’s stated aim of avoiding the ‘judgmental manipulation of conventional coverage’[7]ibid., p. 329. in a manner intended to parallel Conrad’s detached, ironic narrative voice (though Conrad himself does not, in fact, shrink from issuing clear judgements). In practice, Ogilvie’s chosen form has a different effect: in restricting the film to a certain number of camera angles and locations, he turns it into a game played with the seen and unseen, what can be shown and what cannot.

This too seems carried over from Conrad’s novel, which has its own calculated elisions – starting in the first chapter with the description of Verloc’s shop, in which the nature of the merchandise is clearly indicated but not explicitly described. Ogilvie on this front is almost equally discreet, yet the film’s whole tone is inflected by the notion of pornography kept under wraps: scattered throughout are odd hints of the salacious, which can be blunt but generally stop short of full disclosure. The minister is glimpsed on Skype having his way with his ‘rent boy’ Toodles (Jim Coulson), while the scenes of Verloc and Winnie in bed together don’t proceed beyond foreplay, encouraging speculation on what further unseen material might have been captured by Heat’s cameras.

All this is paid off, after a fashion, in the film’s two ‘money shots’, which deliver the goods in terms of horror rather than sex; as such, they seem intended to make up for all the previous gaps in the narrative, including the elision of the crucial moment when the bomb goes off. The first of these shots comes in the aftermath of the explosion, and is shocking enough to prompt a rethink of what Ogilvie is up to in general: the sight of Stevie’s bloody remains on a bench in the morgue, unrecognisable from the likeable character we’ve come to know. The second shot shows Verloc’s dying agony after he’s stabbed by Winnie, who remains beside him in bed as blood oozes from his mouth; this too is shocking, especially following the sight of her masturbating him under the covers a few moments earlier.

What comes through here is less pathos or social criticism than a kind of amoral showmanship, inviting comparison with the most celebrated earlier screen adaptation of The Secret Agent: Alfred Hitchcock’s Sabotage, which updates the action to its own present day of 1936. As is generally recognised, this is one of the best films of Hitchcock’s British period – though, in a sense, it has little to do with Conrad, whose plot is altered and streamlined for the filmmaker’s own purposes. The political dimension of the narrative, for instance, is cynically dismissed: in Hitchcock’s film, Verloc (Oskar Homolka) and his fellow terrorists are portrayed as crooks, pure and simple. Nor are we told much about the mysterious forces higher in the chain of command, though a Scotland Yard superintendent (Matthew Boulton) indicates they’re far too powerful to be worth pursuing.

This leaves space for other concerns: the inspired move of Sabotage is to make Verloc the manager not of a bookshop but of a cinema (though he, too, may dabble in pornography, judging from a fleeting comment about the films he allegedly screens after dark). Thus the film becomes something close to a Hitchcockian self-portrait; Verloc is, literally, a showman, under orders to astonish the city with a truly dramatic big bang. Hitchcock takes this metaphor and runs with it, filling the film with ironic reflections on the relation between artist and audience – in contrast to Ogilvie, whose nearest equivalent to Hitchcock’s Greek chorus of Londoners is a carriageload of train passengers immersed in their phones.

All the ironies of Sabotage lead up to the film’s climax, in which Verloc hides his bomb in a can of film that his unwitting brother-in-law Stevie (Desmond Tester) – here, a child, rather than an intellectually disabled young man – is dispatched to deliver to Piccadilly Circus, only to be waylaid by one spectacle after another. The death of this Stevie, who takes an entire busload of Londoners with him, is a shock on a different level from anything in Lone Wolf – and one that Hitchcock later claimed to regret, feeling it went too far for his public.[8]See François Truffaut, Hitchcock/Truffaut, Simon & Schuster, New York, 1967, p. 76. Not long after, he would depart for Hollywood, where he would bring his own showmanship to another level, while avoiding the danger of having his explosions go off too close to home.

Ogilvie, for his part, still seems to be grappling with the question of how to stage a ‘victimless atrocity’: that is, how to use limited resources to seize attention, without either stranding us in boredom or pushing things too horrifically far. In this light, the most telling image in Lone Wolf might be the overhead shot of the miniaturised Tudor village in Fitzroy Gardens, which appears deserted at the outset as it accompanies Ogilvie’s writer/director credit, and reappears much later as part of a split-screen montage, with Verloc now lurking about. In those narrow, empty streets, we might sense another image of an abstracted world, and, beneath that, the fear that troubles so many filmmakers in Australia and beyond: that perhaps, after all, nobody is watching.

Endnotes

| 1 | Jonathan Ogilvie, ‘From Rainy Soho to Sunny Kings Cross: Remapping and Contemporizing Joseph Conrad’s The Secret Agent’, in Casie Hermansson & Janet Zepernick (eds), Where Is Adaptation? Mapping Cultures, Texts, and Contexts, John Benjamins Publishing Company, Amsterdam & Philadelphia, 2018, p. 324. |

|---|---|

| 2 | ibid. |

| 3 | ibid., pp. 324–6. |

| 4 | Joseph Conrad, ‘Author’s Preface’, The Secret Agent: A Simple Tale, Vintage Books, London, 2020 [1907], pp. xxi–xxii. |

| 5 | ibid., p. xxv. |

| 6 | Ogilvie, op. cit., p. 324. |

| 7 | ibid., p. 329. |

| 8 | See François Truffaut, Hitchcock/Truffaut, Simon & Schuster, New York, 1967, p. 76. |