Seen any good movies starring disabled people lately? No? Well, neither has Rob McNamara, Public Education Officer at Yooralla, and he thinks it’s time for a change.

Rob is an articulate and engaging person – the fact that he glides into his office in an electric wheelchair is merely incidental and almost irrelevant. Rob spoke fluently and with humour about the way in which so-called “disabled” and/or “handicapped” people are represented in films.

Generally speaking, he suggested that they could be divided into two groups, the first of which he labelled The Villains. Most viewers are only too familiar with the chilling sound of Long John Silver’s or Ahab’s wooden leg, or the frightening sight of Captain Hook’s claw.

The two classic hunchbacks, Richard of Gloucester and Quasimodo of Notre Dame, are other examples of disabled people who are renowned for exciting fear and revulsion, despite their redeeming virtues of courage and loyalty. Richard III’s cry of “My kingdom for a horse” is after all, one of the most nobly brave moments in drama, as is Quasimodo’s equally Senecan scream of “Sanctuary!” – especially in Charles Laughton’s classic movie impersonation.

The message of such films is basic, and clear: disabled people are grotesque figures who inspire dread; they should be avoided at all costs.

Rob used an interesting term to describe the second group: The Super Crips. These are the characters who, both despite and because of their disability, are shown to be superhuman, and thus worthy of our admiration.

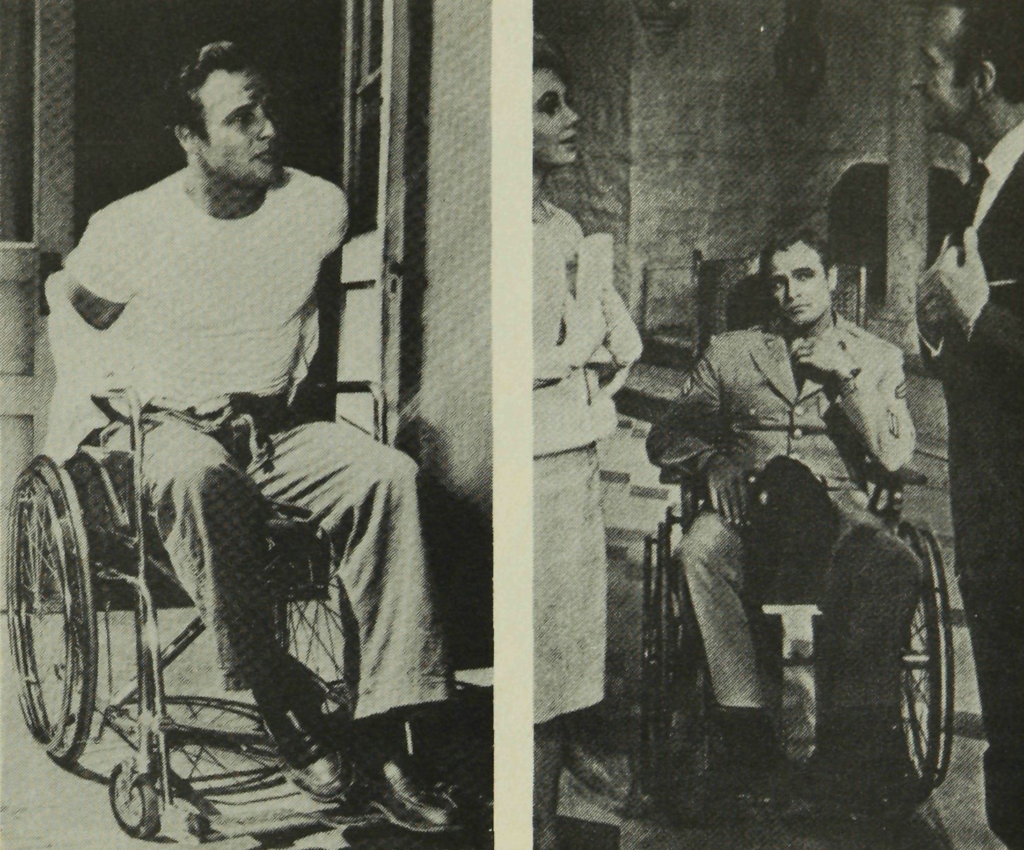

They nearly always, however, invite our pity at the same time. Remember the romance and heroism of Marlon Brando’s paraplegic veteran in The Men, or Jane Wyman’s blind woman in Johnny Belinda? And didn’t you cry when Walter Pidgeon, in John Ford’s How Green Was My Valley, persuaded the little crippled boy to “Get up and walk”? Or when so many different Heidis likewise convinced so many Fraulein Klaras that the ability to walk was merely a matter of willpower?

Window to the Sky went one step further – or changed the gait, at any rate: all cripples can ski, according to the successes of the beautiful heroine. Or they can skate – as in Ice Castles.

But any chance such films ever had for achieving some semblance of reality was ruined by their overriding sentimentality. A Patch of Blue‘s treatment of blindness was also marred by over-emotionalism, though the movie had other dramatic objectives, like highlighting racism in America.

Blindness also provides the basis of the plot for both Blind Terror and Butterflies Are Free. In Blind Terror we see Mia Farrow as an attractive, active and reasonably independent woman, but she still needs her boyfriend (Norman Eshley) to come galloping – literally – to the rescue in the end. Rob McNamara acknowledges a positive shift in Butterflies Are Free, in which the hero’s disability is actually treated with some humour: (“Felt any good books lately?” asks Goldie Hawn, after stumbling into “What are you – blind?”).

Rob’s pretty sceptical, too, about T.V.’s offerings, with a couple of exceptions. Raymond Burr’s wheelchaired detective, Ironsides was a classic Super Crip, surrounded by a cast dedicated to rhetoric and emoting.

The same criticism can be made of Leave Yesterday Behind, recently screened on the 9 network. Even Princess Leia (Carrie Fisher) could not save this one. The blurb from T.V. Week says it all: “A happy-go-lucky college athlete is paralysed in a polo accident, but with the help of a beautiful girl he learns to love and win again”.

Before we leave the violins and the schmalz, there is another genre of movies which Rob mentioned for a specific purpose. How can we forget those beautiful tragic heroines of Love Story, Sunshine and A Warm December, who continue to live “normally”, while knowing every week may be their last?

The similarities are obvious: audiences respond to the girls’ beauty and courage with pity and admiration. The trouble is that audiences also tend to confuse these terminally ill patients with disabled people who are simply getting on with their lives. Rob was anxious to point out the difference: “Disabled people are not sick. Some sick people may be disabled, but that’s just incidental”. He explained that rehabilitation programmes always stress this point: paraplegics and quadraplegics are encouraged to maximize what is left to work with, rather than to lament what is lost.

Rob then took some trouble to clarify the meanings of often mis-used terms. These definitions are those being used by the United Nations during the International Year of the Disabled Person – and note the preposition: it started out as for the Disabled Person, a shift of emphasis demanded by the disabled community.

Rob cited three terms: firstly, impairment, defining what is medically wrong with a person. Then disability – the consequence of impairment, usually involving some limitation of ability. And lastly, handicap – the relationship between the disabled person and the rest of society.

As Rob says: “You can do something about handicaps. Handicaps can disappear – disabilities can’t. No movies make this distinction clear, although some of the documentaries make the distinction between sick and disabled.

“It is society itself which reinforces, as well as responds to the cliches and sterEotypes of beautiful people”, Rob says. He objects to the way in which certain stereotyped images are exploited. For instance, whenever he wants to raise money (through, say, a Telethon), he has been told to find “a cute kid in calipers, preferably with an animal”.

He went on emphatically: “What we’re not getting on screen is adult, assertive, sexual, employed, ordinary, family, mobile people – who also happen to be disabled”.

But all is not quite as hopeless as it sounds. Firstly, on television there are a couple of exceptions to the rule of sentimentality. One is the American serial Kaz. This is the story of an ex-convict who studied law and graduated in prison. An early episode showed him encouraging a mildly retarded young man to give evidence at a trial. The witness retained his dignity and sense of humour in the face of considerable harassment, confidently assuring the prosecution that he was “slow … but sure.”

This clearly illustrates a particular perspective which is worth encouraging: namely that we all occupy a place on a continuum, ranging from the so-called sub-normal to the genius or super-normal. Whoever we may be, and whatever our physical and mental capacities, there will always be someone both ahead of and behind us on this continuum.

Television is also to be given credit for such powerful documentaries as the B.B.C’s On Giant’s Shoulders, the story of what happened to a seriously deformed thalidomide baby who was adopted by a middle-aged couple. Born without arms or legs, blind in one eye and with two flippers at the bottom of his torso, Terry Wiles could only be played by Terry Wiles.

He is not out to wrench at anybody’s heart strings. He knows and copes with his physical limitations, while his spirited personality and obvious love of life are what predominate.

His performance strikes a major blow of defiance. Who but he could play the part so authentically?

In similar vein is the programme Lefty, produced by James Thompson and Gina Rester. This uses a factoid technique to dramatize several months in the life of Carol Johnston, a one-armed gymnast. Carol, born with a shortened stump for her right arm, portrays herself. In fact, there are no professional actors in the one-hour programme, but all the participants are “acting” in an effort to capture moments from Carol’s past.

On the local scene, a young actress who was crippled in a car crash at the age of fifteen has managed to continue her successful career. Louise Phillip is currently seen in Cop Shop, playing the part of Claire, a wife and mother, who happens to be in a wheelchair.

Of all the feature films which Rob mentioned, he clearly considered one to be a major landmark. It is the award-winning Coming Home, starring Jon Voight as a paraplegic Vietnam veteran, and Jane Fonda as his girlfriend, with Bruce Dern as her husband.

There are several reasons why this movie is so important. Firstly, as Rob pointed out, “This is not a film about a cripple, but about the 60’s and war – specifically the Vietnam war.” Here at last is a disabled person who is shown to be both politically and sexually active. In fact, not only is Voight allowed to be sexual, which Rob says is significant in itself, but he is able to communicate sexually with an “able-bodied” woman – all without being romanticised.

Equally significant is the fact that he actually contributes to her growth as a person. Why has it so often appeared incredible that disabled people are able to give us something? (“Us”, in this case, being the odd people that the disabled community often refer to as straights or – better still – verticals and/or uprights).

Rob picks out favourite sequences in Coming Home, such as the rehabilitation scenes in the hospital. The depicted anger and frustration are very accurate, he says. He’d like to see the Voight character now. “In 1981 – theoretically the benchmark year for disabled people – that man is a dozen years older, and has no war to catalyze his anger.”

War has been a catalyst for minority interests before Vietnam, of course. In the last issue of Metro, the article ‘Films, Women and Work’ asked: “The women and work film – it’s wartime and suddenly women can do anything. Why did it take war to make inroads on entrenched attitudes to female employment?” (p. 30).

Rob agreed that disabled people may be facing struggles analogous to those already engaging women and blacks. Try these four arbitrary stages in the cinema’s reflection of the struggles: passivity; protest; over-compensation; liberation and acceptance.

Look at one actress, the same Fonda from Coming Home, progressing non-chronologically through the quartet from A Doll’s House to Barbarella to Klute to China Syndrome.

Or one actor, Sidney Poitier, known in the movie industry for years simply as Tom, who has gone from the cabin to A Patch Of Blue to besting Tracy and Hepburn in Guess Who’s Coming To Dinner? and on to swatting Steiger in In the Heat of the Night.

Woman and black people are no longer a novelty in films. Sex and colour seem, in the cinema’s more sanguine moments, to be becoming incidental. (Billy Dee Williams, for instance, at a recent Empire Strikes Back press conference in Melbourne, rolled over an Ocker question about token spades in outer space by replying, “I don’t consider myself to be playing a black man out there, or anywhere else. I consider myself an actor.”

The disabled have been through The Hunchback of Notre Dame to How Green Was My Valley to Coming Home. Rob is waiting for the quartet to be completed, so that disabled people in films will finally be taken for granted. He smiled: “We’re into consciousness-raising, you know.”

Perhaps an Australian actress will make the breakthrough. Louise Phillip’s role in Cop Shop has been mentioned already. She accepts very few inevitable restrictions to her career, simply because she is in a wheelchair.

Louise told Metro: “My job is to entertain people, and I’m not a disabled entertainer. Some producers and directors feel I’d be out of context, and I agree about period dramas or Shakespeare. But I simply do not see why I can’t appear in any contemporary work.” Louise is eager to get back to the stage, possibly with the Hoopla company. “What more immediate attention grabber could there be on stage than my wheelchair?” she asked in a tone which spontaneously combined the combative and the vivacious. “I’m way ahead of other actors from the moment I come on.”

Louise says people are bound to get past the wheelchair as the centre of attention. And she accepts Rob McNamara’s analogy with a dramatic character’s simply being female or black no longer automatically elevating them (in Tom Wolfe’s useful phrase) “to the level of theatre.”

Part of Rob’s work for Yooralla is to go out to schools and talk to classes. This is when documentaries are really useful. Rob only uses four or five films (“the only quality ones available,” he says, “though no doubt the I.Y.D.P. will produce many more, as film producers jump on the bandwagon.”)

The film he uses for classes up to about Year 10 is Get It Together. Set in America, it is about a paraplegic in a rehabilitation centre. Rob uses this for younger students because it is very up-tempo and positive in its approach – the hero gets round in his souped-up, cut-down wheelchair.

For more mature students, Rob uses the British documentary Like Other People (Kestrel Films 1974). The makers of this film, Ken Loach and Tony Garnet, are already well-known for their previous productions, Kes and Family Life.

The latter traces the causes and results of emotional repression in a teenage girl. In Like Other People, Loach and Garnet turn from psychological to physical deterioration.

The film looks at how a woman with cerebral palsy copes with everyday life, taking in such issues as family attitudes and employment problems. Rob says that viewers find the documentary particularly demanding, because the woman’s own voice is used, despite a speech impediment. Allowing the disabled to literally speak for themselves is a feature of nearly all the documentaries Rob mentioned: “Necessary for both credibility and integrity”, he says.

There is also a good children’s film available concerned with cerebral palsy, based on an Australian novel, Ivan Southall’s Let The Balloon Go. John Sumner is a young boy who struggles to achieve independence despite his disability and in the face of over-protective parents.

Rob made the point that children are far better able to cope with disabled adults than are adults – they ask all the questions adults are afraid to ask, and then get down to the serious business of going for rides in the wheelchair. Unfortunately, however, disabled children are generally made fun of or avoided by other children.

The major documentary Rob referred to is a recent Australian production called Pins and Needles. This was produced by Genni Batterham of Sydney, who applied to the Women’s Film Fund to make a film about multiple sclerosis and how it has affected her life.

Prior to this, Genni’s only filming experience was one month as an assistant film editor on Chopper Squad, but she went ahead with the project because “I knew a film had to be made”.

The Sydney Co-op’s promo of Pins and Needles describes it as “a brutally honest film”, in which Genni “incorporates her personal battle to come to terms with her disability with broader implications which have a bearing on all disabled people in this society”.

Pins and Needles takes a poignant look at the overall reactions, treatment and acceptance of disabled people. It shows the apparent lack of concern by government and other authoritative bodies for the one million disabled people of Australia, and raises many questions about the possibility of alternatives to the present situation.

Rob finds that the film works “at a very adult emotional level”. Once again, the viewer is asked to watch something which cannot be shrugged off as only a story. The actress is not going to return her wheelchair to the prop room and walk out of the studio at the end of the day’s filming.

Just as Rob pointed out the difference between illness and physical disability, here he stressed that multiple sclerosis is not synonymous with paraplegia. While a paraplegic – traumatically crippled, say, in a road accident — knows the extent of his/her disability and must learn to cope with that, the M.S. sufferer knows that his/her condition is always steadily deteriorating: “It is a disease, as well as a disability”.

Rob says the documentaries all demonstrate that disabled people are usually isolated from the rest of society. It is the average person’s lack of familiarity with any disabled people (especially on a one-to-one basis) which leads to the ignorance, fear and stereotypes that characterize the physically hostile environment.

When I asked him finally what sort of films should be made, Rob sounded as though he really wasn’t asking for much: “We need films which show that the disabled are people – ordinary people with ordinary needs, like income security, mobility and employment.”

Rob wanted a person’s disability not to be regarded as the critical element in his/her personality. He quoted approvingly an American advertisement he had seen, featuring a man in a wheelchair, seen from the back. “Those who didn’t know him”, ran the ad., “called him a cripple”. Then you see the man from the front, with F.D.R’s familiar pince-nez and cigarette-holder in evidence. “But those who did”, continues the text, “called him ‘Mr. President’.”

“What more can we ask?” Rob smiled disarmingly. “I think that to be ordinary would be lovely”.