It is not a woman in the nude that is indecent, but a woman whose skirts are tucked up that is …

– Diderot

From an indeterminate source in my childhood I had been exposed to the idea that some distinction could be made between nudity and nakedness, one I later discovered came from the art historian Kenneth Clarke. Nudity is about exposure, it requires a kind of revelation of the body from concealment. Nakedness is the way we are born. It was the more innocent state of nakedness I was driving at when, somewhere in my discernible prepubescence, I levered my bicycle up my suburban street and hurtled back down naked from the waist up. The pleasure taken was not purely sensual or tactile but more in the rebellion. And rebellion and nudity were linked together in the Australian cultural imagination in the seventies.

In the suburbs that followed the Yarra river out of Melbourne there were outposts of skinny-dipping hippies still purposively not looking at their ‘going nude’ and, it seemed to me peeping from the other bank, achieving considerable success at being ‘naked’. It gave me scope for a reasonably innocent self-display: I could be one of them I decided, though perhaps a little misplaced pedalling up and down a suburban bitumen strip. Indeed, I had an idea that nudity was geographically specific and I was interested to stretch the geography of this nakedness: Can you be nude in suburbia? Is it the location that makes you indecent? I looked to the response from my neighbours in order to suss out what being naked and feminine meant. And, sure enough, Mrs. Smith from across the road was scandalised that a girl should go ‘topless’ and make a spectacle of herself with such overt disregard for decency. Partly through its appropriation as pornographic, nudity was otherwise linked to indecency, against which an enduring Australian sexual conservatism defined and asserted itself as decent.

Most poignant for this ten-year-old was that I was abjectly breastless and would remain sulkily so until all of sixteen. I thought that having no breasts might help me get away with nudity and I rather wondered how one can be topless and breastless at the same time. For Mrs. Smith both my being a girl and my being naked were over-determined as pornographic. Being breastless would have no bearing on the overriding way of making sense of feminine nudity – as topless. That is to say, by 1976 a dominant cultural sensibility of feminine nudity in Australia had emerged that would come to invest itself increasingly in the very meaning and possibilities of what I call feminine visibility; that is, how women are publicly visible, and therefore how they can participate in the public realm, the male realm, and ultimately the realm of political presence and cultural participation.

At base this was a sexualisation of the feminine that for many women was not unwelcome and indeed, could assist in elaborating a feminist/hippy construction of the liberated natural. It fitted with Germaine Greer’s sexually autonomous and active woman, and it was at this stage still marked with a certain rebellion. However, throughout the next two decades, the association between liberation and nudity began to ring hollow for many women. While feminine nudity and display had initially seemed to bring about a sort of democratisation of the sexual (anyone’s got it), the increasing strictures of this nudity in the media, in terms of youth and beauty, started to set up a new elite of the ‘sexy’. A resistance to the new elite and to the increasing commercialisation of feminine nudity was heard in the feminist catch cries of ‘sexual objectification’ and ‘media exploitation of women’.

At about this point American anti-porn feminists such as Gloria Steinem set up a distinction within the phenomena of feminine nudity between ‘erotica’ and ‘pornography’. It was widely influential here, as was Andrea Dworkin’s analysis of pornography as masculine violence, control and possession of women; and Robin Morgan’s slogan ‘pornography is the theory, rape is the practice’. In retrospect, this argued for a continuation of the separation between ‘good’ and ‘bad’ feminine sexuality, which in turn constructed an absolutism about feminine nudity and how it was anchored to male desire and pleasure, that seemed to advocate a profound sexual and visual conservatism. Unfortunately, their opponents, the pornographers, while claiming to liberate sexuality were also becoming absolute about feminine nudity and by extension the sexuality it was now said to embody. Through pornography, feminine nudity was earmarked by sexism, every glimpse of breast became bolted down to its relation to ‘the male gaze’. It seemed feminine nudity, like ‘wives’ and ‘mothers’, could never be independent of its relation to men and to male appraisal again. What I want to ask here is, between the two vying versions of nudity, that of anti-porn feminism and that of pornography, what happened to variant meanings of feminine nudity in Australia?

Limiting the View

Back in 1976, and not without a sense of having highly intensified zones on my still scrawny and scratched little body, I pulled on a skivvy and wondered how most women managed the difference between drawing attention to these zones for themselves and, out of the blue, having their attention drawn back to them by men, often with hostility. Some overall feminine potential was being remarked on when a boy stuck a stick up my uniform while passing me on a railway bridge. Or, even more frighteningly, when a rat-faced man in a purple panel van scoured the fringes of the bush for me as I fled from some recognition he’d made of me that luckily I’d already sensed was malevolent. As the trucks hooted and business men on trains looked without letting up, I started to feel a little stuck in some triangular definition of my youth, femininity and visibility, that allowed for no interventions of my own. And since my girlfriends insisted that my going ‘topless’ at the local swimming hole was exactly the same as being a playboy model, I knew with real sadness that my nudity was no longer available to me as a site for resistance … or even self-declaration. Feminine nudity, largely thanks to the very media that was claiming to liberate sexuality, had become definitionally stuck, both in how it defined women as culturally valuable and as cultural participants, and in how nudity was defined as necessarily feminine and therefore sexualised.

More recently than 1976, my friend’s daughter pulled a stunt of rebellion similar to my own, which made use of normally covered body parts. By 1993 the possible interpretations of nudity/nakedness in Australia had grown more limited; similarly, she was operating within available interpretations to enact a sort of naughtiness rather than commit a moral outrage to conservative suburban values. At kindergarten, she approached the front of her class for ‘Show and Tell’ to reveal her behind. Keenly interested in the response, she peered around her bottom to see two teachers vacating the room, unsuccessfully suppressing their laughter, and her classmates rolling on their bellies in fits. She was both delighted and, I think, vindicated. What a feminine bottom had meant to her up to that point, I’m guessing, was an almost unjust visual privileging of pneumatic and tanned, barely post-pubescent buttocks and a cultural exiling of all others of less display-potential to tracky-dacks. For her, bottoms were potentially transgressive of the opposition sexy/not sexy; they were an intensely comic site when inappropriately let out into light.

Mooning, of course, is nothing new to boys and men. I couldn’t count the number of times hired buses of, I think, bucks’ night-boys have ‘in-my-faced’ their beer engorged bottoms. Mooning, like nudity, however, is gendered. Instead of being a boysie statement of indifference to social mores, or associated with flashing, perversion and criminal perpetration, for women it rarely gets nasty, it is stuck in ‘cutesie land’ and can hardly help to be viewed as sexually provocative, a visually rhetorical ‘how about it?’ In the limited logic of Western display, feminine nudity can only be about one thing, and this corresponds with the other, still largely singular and conservative version of that ‘one thing’ (sexuality) in mainstream pornography. In this restricted exhibition space, sex and nudity have become tautological. Why would a woman show her breasts? The possible replies to this question have been censored down into a singular plausibility: to sexually excite a male audience. Mainstream heterosexual pornography then works as a definitional limit on nudity and on sexuality.

Taking Culture Onto/Into the Body

Along with this standardisation of feminine display, or what feminists have named a ‘regime of viewing’ which informs everyday ways of seeing women, there is also the standardisation of the feminine body itself. Right at the point when women were demanding public presence and visibility at the end of the last century, the way women were to look became organised around a definition of sexual appeal to do with race, youth and beauty which excluded most women. It also literally standardised the feminine body into sizes, and the margins of variability in the feminine body narrowed in spite of the corset being discarded. Since the beginnings of ‘ready-to-wear’ fashion in the twenties, and its imperatives of normative sizing, Western women have practised new forms of body moulding, which integrated previously removable orderings of the body such as the corset, and relocalised or internalised them into an individual will over the body itself. These new forms of dieting and eurhythmies were hailed then by the burgeoning ‘health is beauty’ movement as ‘muscular corsets’ to replace those of whale bone and metal. Dress liberation had done something curious to the feminine body. Inadvertently, it was asking through new practices and regimes in ‘the care of the self to internalise the strictures that had held the body in place in the Edwardian and Victorian periods. The ‘hygiene and health’ and ‘beauty’ movements of modernity made a new and startling admission about the body; that it was a cultural artefact, that it was debarred from experiencing itself as a biological and natural innocence. It could never again be naked; like Simone de Beauvoir’s ‘made and not born women’, the body had become nude and not naked.

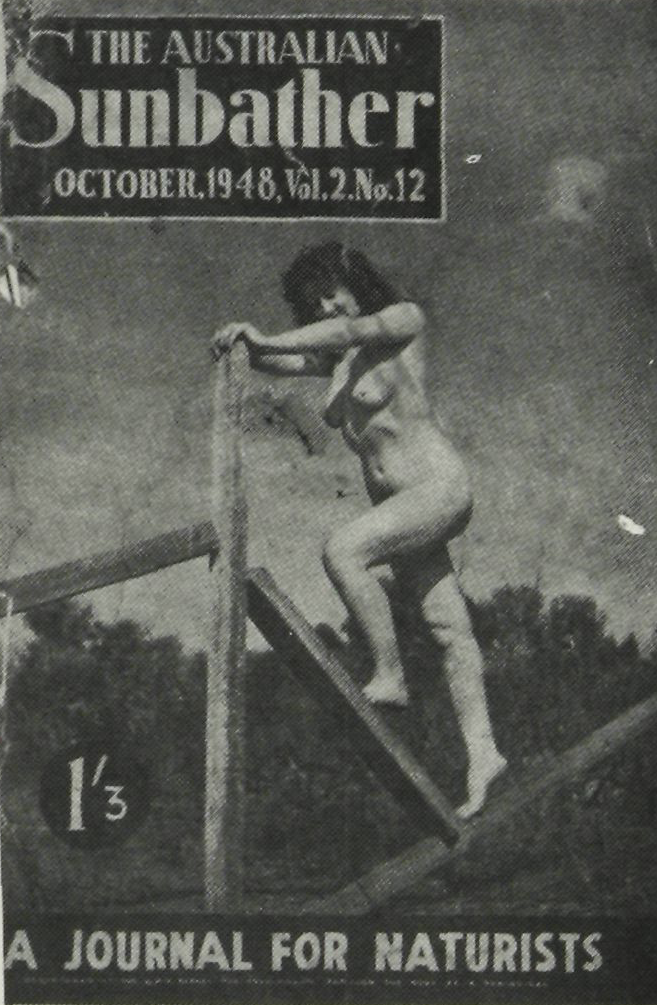

The logic of feminine display and appeal took up a similar fascination in the body as the margins of decency and nudity were being redrawn around bare arms and backs, and rising hemlines. In magazines such as The Bulletin, with its very masculinist leanings, an attempt to rein in the meanings of feminine visibility and pin it down to sexual appeal rather than public presence was exerted in its cartoons drawn by D. H. Souter and its half-scathing, half-visually riveted editorials and articles. This reduction and simplification of feminine visibility was to receive an enormous boost some decades later with mainstream, heterosexual pornography’s reduced version of feminine nudity.

More contemporarily, interventions into the body such as piercing and tattooing have adopted in the West new renditions of ‘sexy’ in drawing together again the motifs of display, marginality and resistance. Similarly, such practices once again mark out the impossibility of ‘nakedness’ as a natural alternative to the culturally beleaguered body. Even my own topless cycling antics were hardly innocent, drawing upon ideas about nudity which were inherited from different smatterings of art history such as the romantics, popularised pseudo-Freudian ideas about ‘repression’, anti-urban hippy statements and feminist sexual emancipation. That is, my ‘nakedness’ was in fact a cultural and political montage. For all its ‘good’ intentions of nakedness, I was nude.

Body piercing and tattooing reiterates the claims of British urban punks against those of Californian hippydom: the natural, naked self is derided as a naivety and the culturally marked body is flaunted as a visual and logical extension and a bodily inclusion of, and participation into, culture. It is the recognition that none of us can live outside cultural and political terms of reference. Given that this enactment, though perhaps not conscious realisation, of the body as irreversibly cultural began with twentieth century modernity, it seems remarkable, a century on, that both anti-porn feminists and pornographers still wish to claim their own versions of a natural or more truthful feminine nudity and sexuality.

Pleasure and Feminine Display

Getting back to the specifics of feminine visibility, a similar attempt at political innocence sets the tone of Naomi Wolf’s The Beauty Myth. In her heartfelt and very compelling (over)view of women’s universal visual subordination she leaves out a vital and, to me, very obvious presence: our ‘complicity’, though I’d rather call it pleasure. Are all women who take pleasure in appearing really just a bunch of suckers for male control? Surely we need a more sophisticated understanding if we are to helpfully tackle the down-side of eating disorders and, more broadly, to understand the significance of feminine visibility to women’s cultural and political inclusion and participation. Just what does feminine visibility mean to women?

If we understand that real pleasure and legitimation are felt by women finding an audience and notoriety because of their being-looked-at (Kate Fischer is a classic, self-generative and, at times, wonderfully ‘brazen’ example), and if we acknowledge that women themselves are doing billions of dollars worth of magazine-looking and cosmetic-buying, then the old claims of ‘women as sex objects’ begins to describe something more specific to women’s desires and pleasures than previous explanations embodied in an audience of whooping, power-bolstered men. I wouldn’t go so far as to argue on the strength of this evident pleasure that feminine visibility has achieved a ‘free-for-all’ kind of political nakedness or innocence. Even if women are looking and buying on the precepts of their potential ‘to-be-looked-at’ too, on the precepts of the pleasure in their own sexualised display, this doesn’t redeem table-top dancing as being, say, really a site for the expression of an egalitarian business world where women executives can butter up their clients too. That many women participate in their sexualised display doesn’t by extension make pornography exempt from criticism.

Rather, it points to the need to complexify the terms of the discussion, and the need for us to critically look at the operations of feminine nudity that allows for pleasure-in-appearing and yet can still recognise its cultural and political inheritances as well as its different determinations of power. In my view, feminism needs to think with and beyond its often intense theorisations of woman-as-spectacle and as ‘object-to-be-looked-at’, through to a notion of feminine visibility which can think about display from the other side of the picture, or screen. That is, to ask what it is for women to appear? How has display, exhibitionism and visibility been worked into feminine identity since the advent of photography, cinema, commodity culture and women’s new modern public presence?

While I have argued above that we are, or dominant white culture is, coming out of a period of reduced ways of seeing women, there are still many different contexts of this seeing which then set the stage for and sometimes limit its possible meanings. I would argue that ‘lesbian chic’ has provided a new point of permission, or identification (or is it appropriation?), to heterosexual feminist women invested in their own sexualised display. Yet, true to its impermanent form, meaning wriggles into new guises in different venues or exhibition spaces: Are snaps of sleaze ball nudity still performing the same claims for gay and lesbian visibility and cultural presence in Picture magazine?

This last New Year’s Eve I was caught, inadvertently, in the incommensurable meanings of lesbian display and a heterosexualised controlling gaze. The performative spaces or localities of nudity overlapped ironically after I had been at a gay and lesbian dance party outside Byron Bay. As a currently practising heterosexual I have to confess I wondered whether in donning a completely transparent top I was colonising the display techniques of lesbian dance-party strut. And I have to add that in amongst the difficulties of queer inclusiveness and my own discomfort at heterosexuals sometimes shrugging off an acknowledgment of their own privileges in plonking themselves within this category, I also feel enormous pleasure and relief at the sites of safe, unharassed display gay and lesbian club and dance spaces set up. These are questions I raise a little shyly, always a bit self-conscious about interloping into these spaces. But the specificity of this display was almost burned into my flesh after the dance when I was pulled over by 16 fiercely heterosexual cops to be breathalysed. The ranks were meaningfully asked, ‘Which of you officers would like to breath-test this young lady?’ I inwardly shrank back; ogling became a clear device of authority and control when I was mock-warned that I had a negative reading. Confused, I asked what that meant and was told it meant I had to go with these officers and ‘do whatever they said’. Yuck! My hands shook when I restarted the car.

Still, while we may ponder backwards and forwards between the display/exposure sites of a naked women on a dog collar, Sharon Stone’s rather confusing version of voluntary strip-searching in Basic Instinct, Lesbian chic-raunch, and Roseanne’s breast reduction, the operations of power are vacillating wildly. Power doesn’t work in only one direction – from oppression to subordination – in feminine visibility. Yet, for all of this, the operability of youth, weight and idealised beauty seem to remain the same and this needs a critical gaze. Even at lesbian dance parties it seems younger, sleek women have a greater prerogative to display. All of which makes Kaz Cook’s axiom ‘You Are Not Your Buttocks’ one relieving and still confronting cultural moon, and leaves for Madonna one last action of mainstreamed radicalism: simply that she grow old and still take off her clothes.

Prising Open the Porn Debate

I’m arguing here that we consider feminine nudity as in fact culturally indebted and politically invested, and we take to its pleasures and its uses a history of the ways that it operates and performs power. It’s a long task and one I’m beginning as an alternative to past activism in the pornography debate. Indeed, I would argue that the pornography debate makes this complexity and rethinking about feminine nudity, particularly its uses of power, virtually impossible: it is a system of speaking placements that cannot make sense of new approaches. In this arena the discussion is pre-ordered from speaking positions which have to deal with the spectre of causality and harm: that pornography causes violence, for proven harm is the only liberal basis for state intervention into ‘speech’. There is very little space to suggest the usefulness of thinking about feminine nudity as having a history, and that mainstream pornography has determined its conditions of visibility which are now, as a result, anchored down to a conservative and unexplorative world view. More dangerously, a world view which claims to have the only authorised version of feminine nudity and positions all alternative views as sexually ‘repressed’.

I want to take up this accusation. It was ironic that in expressing the hope for intrusions into this world of dated 1950s ‘tit and arse’ cheesecake, the hope for something more (‘more’ not being ‘the truth about sex’), something that spoke of the same unknowability that desire itself speaks, that this risked the accusation of being sexually repressed. The paradoxes of the statement struck me then while the polarisations were massing on either side of the pornography debate. Exactly who authors a standard of sexual success with the confidence that can then allow them to diagnose alternative voices with sexual repression? And isn’t the very attempt to author such a standard of sexual success both supreme arrogance and perversely self-defeating? Because, isn’t a standard of sexual success a fixed definition of sexuality with an inflexible outline in bold that refuses innovation, challenge and resignation into play and potential? For me this is precisely ‘repressive’, and it’s these sureties and definitional limits that I’d argue need to be resisted more than anything else in mainstream pornography.

Exactly like some parts of anti-porn feminism, mainstream heterosexual porn wants to assert a definitive version of sex and to be the final author of what constitutes legitimate, even permissible, feminine nudity. Ironically, both anti-porn feminism and pornography insist they have the more accurate version of sexuality, and the outcome for both is that they are prescriptive and dismissive of alternative versions. Mainstream pornography (as a self-conscious industry and visual practice) wants to pin down feminine nudity to a single purpose: male arousal. Against contesting definitions of this feminine display it calls upon specious notions of sexual liberation as a way to claim, ultimately, that they have the certified (by their own hand) version. Having put up their own sexual and visual umbrellas, mainstream porn wants to argue that it is fighting valiantly ‘under’ the shadow of sexual repression.

Their new incarnation of the charge of ‘wowserism’, or repressed/repressive, is that of the ‘politically correct’. To speak as someone who resists political correctness is to speak as though you have no political allegiances, which is a disavowal as well as an illusion. The censoring accusation of political correctness is also an abnegation of a usually conservative ideology, hoping to pretend that simply because your politics fits in with the status quo and is therefore mostly invisible, really you don’t have a politics or a correctness of your own. Within the pornography debate, 9 times out of 10 it is a conservative sneer, an indictment of the new right attempting to look marginalised and therefore radical. While aspects of feminism have rigidified, as other feminists were the first to identify and resist, ‘political correctness’ is more often the new cultural-critical cringe. In the pornography debate it’s a handy device of exclusion to a forum that wants to reiterate its truths over and over again to invited and unchallenging members.

But, as suggested above, some feminist approaches to pornography have been in danger of making the same mistake. The local pub changed hands recently after another attempt of erotic dancing failed to spin a dollar. Yet the new owner has regurgitated the old faithful of topless barmaids between, I suppose, the domestically negotiable hours of 5 and 7pm. Not so many years ago a feminist objection might have made itself felt with women demonstrating out the front, arguing that women are more than just ‘sex-objects’. We were ourselves stuck within our own feminist iconography, an irreconcilable distinction made by nineteenth century feminists between women being out of their homes and publicly visible to achieve cultural participation and demand political representation, and those frivolous and narcissistic ‘flappers’ just out to exploit their hard won freedoms, look gorgeous and have fun. Again, ‘good’ and ‘bad’ feminine visibility.

As women have become themselves producers of images of women the uses of feminine nudity and display have complexified. Witness the mutable power relations in Jane Campion’s The Piano (1993): that the slow strip was bound up in an economic bartering was clear, though whether this automatically removed Ada (Holly Hunter) from experiencing her own pleasure and bargaining power was less certain. Witness also the scene in Muriel’s Wedding (1994) in which Muriel/Mariel’s (Toni Collette) hilarity at having her clothes wrenched off and the beanbag accidentally emptied beneath her is a charming dismissal of the more conventional certainties of Hollywood sexual passion (read prowess). It allows for the rare chance that desire might be, among other things, helpless and even comic. Like nudity, and the ways in which desire attaches to nudity, it might (with any luck) never be definitively experienced or understood.

It seems that the meaning of objectification has for now escaped the old orderings and slipped out into less concrete interpretations. These slippages create room for some Utopian projections here: imagine ‘topless’ describing more than a restricted view of restricted feminine body types for a restricted male audience. However, in terms of hetero-mainstream viewing – the dominant vision and version after all – we still have some way to go. Unexpectedly, it has been Paul Verhoeven’s Showgirls (1995) which has asked, without answering, the confusing bundle of questions that artist Jeff Koons also asked in his performance-marriage to porn star and Italian member of parliament Cicciolina: How does the pornographic merge with art? At what point in this definitional untangling can women as sexualised objects of display claim a site for artistic integrity, for pleasure and for their sexualised display being clearly outside the precincts of a visual whoring? What if, as in Showgirls, these boundaries are never assertable? Where does this leave the object-woman? How should she act? And, what should she wear when supposedly not attracting a lucrative and legitimising male gaze?

Cluttering the Landscape of Feminine Visibilities

The best tactic in the face of this certainty about what an (always tanned and pert) bottom or bosom (or feminine nudity) can mean is to confuse and upset those definitions. I have a new, perhaps less naive, rendition of my topless cycling stint: a group of friends enter the local pub between 5 and 7pm, sit down and without looking for any response calmly remove their ‘tops’, go to the bar and order their drinks. They’re on the wrong side of the sexual and economic divide, they’re not having a go at the barmaid, they ignore the men. Indeed, some of the friends are men. Worse, their breasts sag, they’re uneven, they’re randomly too big or too small or not there, some however, are just like the barmaid’s (the point not being that her breasts ‘lie about women’ and that theirs somehow manage to ‘tell the truth’). I’d wager a guess now that they’d be asked to leave. But, when they refused what kind of charge could the police lay on them? Involuntarily stripping in a nightclub without ‘tasty’ police attendance? Indecent exposure?

I’m not completely convinced that this would change the Australian ‘face’ of nudity. Reserving largish doubts I maintain the hope, however, that it would at least introduce confusion. It would elaborate the boundaries of what is the dominant Australian cultural version of feminine nudity, and thereby draw attention to its own ‘repressions’.