The concept of the Stolen Generations is likely impersonal, distant, even archaic to many non-Indigenous Australians. After the Apology (2017) puts a face to the thousands of women and men dispossessed by successive Australian governments in the twentieth century. The first feature documentary from author and activist Larissa Behrendt, it gives a voice to the Aboriginal families still being displaced by current methods of forced child removal. But the film’s greatest asset is its dedication to deep listening – a spiritual skill that requires presence, empathy and resilience from all parties. It’s hard work, and everyone’s got to do it.

On 13 February 2008, then–prime minister Kevin Rudd issued a long-awaited formal apology to Australia’s Stolen Generations: the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples removed from their families by Church and state from 1869 to 1969. Rudd’s action, as per his speech, sought to ‘turn a new page in Australia’s history by righting the wrongs of the past’.[1]‘Apology to Australia’s Indigenous Peoples’, Parliament of Australia website, 13 February 2008, <http://parlinfo.aph.gov.au/parlInfo/search/display/display.w3p;query=Id%3A%22chamber%2Fhansardr%2F2008-02-13%2F0003%22>, accessed 6 February 2018. Just two months into his prime ministerial appointment, he sparked standing ovations across the country – from the lawns of Parliament House to community centres, such as that in Redfern[2]‘Apology Day at Redfern’, Sydney Oral Histories, City of Sydney website, <http://www.sydneyoralhistories.com.au/stories/apology-day-at-redfern>, accessed 6 February 2018. – with his progressive gesture.

Ten years and three iterations of Parliament later, After the Apology makes a case that the Australian Government is creating another stolen generation. Despite Rudd’s words of remorse, forced child removal has not decreased since his deliverance. In fact, as the affecting documentary shows, Aboriginal children are still taken from their kin and transferred to out-of-home care at alarmingly high rates. Shortly before Rudd’s speech, there were 9054 Indigenous kids in out-of-home care across the country; by 2016, that number had risen to 16,816.[3]Figures cited in After the Apology. This is not in line with any broader national trends, as Indigenous children are ten times more likely to be removed from their families than their non-Indigenous counterparts.[4]ibid.

After the Apology follows four grandmothers – Suellyn Tighe, Hazel Collins, and sisters Jenny and Debra Swan – who take on the welfare and judicial sectors in a bid to get their grandchildren back. Along the way, they meet countless families dislocated by the racist policies and procedures greasing the cogs of this traumatic practice. So the four women set about fundamentally changing the system, with Behrendt documenting their feat.

Behrendt translates collective anger, grief and intergenerational trauma for the screen with tact and solidarity … Tighe, Collins and the Swan sisters are treated with the utmost respect and compassion, which they return to the filmmaker through their candid disclosures.

The Grandmothers Against Removals (GMAR) movement has a call to arms heard throughout the film: that ‘Sorry’ means ‘you don’t do it again’. This maxim reminds us that sincere apologies aren’t just symbolic. They require action and amends, attitudinal and behavioural change. But, in the decade since Rudd’s apology, it seems to have been business-as-usual at the New South Wales Department of Family and Community Services (FACS). As for the rest of Australia, we tuned in to the televised broadcast then went back to work, or flicked over to Kerri-Anne. We may have heard what was happening, but did we really listen? After the Apology wields such uncomfortable home truths, not to wound, but to wake us. It’s time to pay attention.

Hearing

Behrendt is the professor of Indigenous research at the University of Technology Sydney, and is an author of fiction and nonfiction. Her first documentary, the NITV-commissioned Innocence Betrayed (2013), followed the justice-seeking families of three murdered Aboriginal children, whose killer was never convicted. In her capacity as a lawyer, Behrendt herself worked on the small-town case in the early 1990s. She returned to Bowraville twenty years later as a documentarian, determined to show how the justice system had failed the families of Colleen Walker-Craig, Evelyn Greenup and Clinton Speedy-Duroux. The case remains unsolved.

As a director – and a Eualeyai and Kamillaroi woman – Behrendt translates collective anger, grief and intergenerational trauma for the screen with tact and solidarity. With a background as a barrister that challenges clichéd notions of lawyers being duplicitous money-grubbers, Behrendt is able to beget brutally honest revelations from her subjects, who are evidently more than just ‘subjects’ to her. In After the Apology, Tighe, Collins and the Swan sisters are treated with the utmost respect and compassion, which they return to the filmmaker through their candid disclosures. With their hopes repeatedly dashed by FACS, the grandmothers – and numerous other women and men featured – obviously long for someone who’ll just listen to them and take their grievances seriously.

This is palpable in several observational scenes documenting a ‘town hall’–type meeting between frustrated mothers and FACS employees. In a sterile community centre, the women lay bare the lies and errors that led to their dependants being forcibly removed. Even as the discussion reaches fever pitch, the administrative mouthpieces sit with uniform poker faces, contractually obliged to show no mercy. Desperate to feel truly heard, one particularly ferocious mother could be characterised as shrill, bossy, hysterical.

It’s exactly this type of reductive, paternalistic and ethnocentric thinking that got this whole mess going, over a century ago. In an interview at her home, Jenny Swan explains that Aboriginal culture is matriarchal; this is inherently at odds with white Australia’s patriarchal ideologies that drive law, policy and governmental procedure. Behrendt clearly gets this. Her identity as an Aboriginal woman – one whose grandmother was a member of the Stolen Generations, and whose father grew up in an orphanage – means she has a level of lived experience necessary to identify with the women’s stories.[5]Larissa Behrendt, ‘Director Statement’, in Pursekey Productions, After the Apology press kit, 2017, p. 31. She also has the national platform to amplify their accounts beyond the walls of a conference room, which she accomplishes with integrity, understanding and vision.

After the Apology features talking-head interviews, observational sequences, archival footage, still photography, text on screen, dramatic monologues and animation … When viewed as a homogenous whole, they illustrate the duration and scope of the national epidemic of child removals.

Seeing

After the Apology features talking-head interviews, observational sequences, archival footage, still photography, text on screen, dramatic monologues and animation. Such eclecticism is a bold move, and some elements are naturally more effective than others. When viewed as a homogenous whole, though, they illustrate the duration and scope of the national epidemic of child removals.

On 11 May 1995, a national inquiry to investigate the enduring effects of removing Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children from their families commenced. Two years later, a 680-page report titled Bringing Them Home revealed the experiences of 535 Indigenous people devastated by forced child removal.[6]Australian Human Rights Commission, Bringing Them Home, April 1997, available at <https://www.humanrights.gov.au/publications/bringing-them-home-report-1997>, accessed 6 February 2018. In After the Apology, some of these gut-wrenching submissions are performed as monologues delivered to-camera: Bianca Cruse, a Cabrogal woman of the Darug nation, embodies three different teen girls, each taken from their families in the 1960s. She recounts episodes of bullying, rape and systematic dehumanisation while fixing her gaze on the viewer. Though the experiences she portrays are historical, her contemporary dress and modern, urban surrounds speak to the abiding consequences of these traumas. The result is startling.

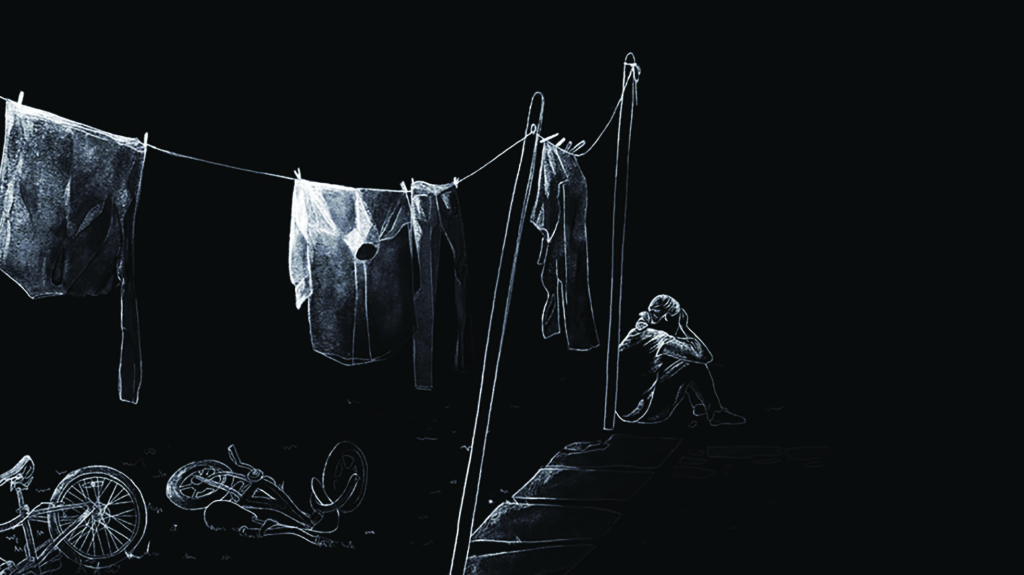

In contrast to this heightened realism sit several animated sequences that feel comparatively ethereal. Behind a rotoscoped veneer, Donna, Kerry, Audrey and Barbara describe their recent experiences of having children and grandchildren essentially stolen. In several cases, the state community services department had been given false information about the women’s families, with the babies taken on the basis of drug use, animal faeces, apparent abuse or neglect – even though these reports were later found to be incorrect.

Then the bricks that make up Donna’s house crumble around her hollow, grey and black form. Audrey sits cross-legged in negative space, overshadowed by skyscraper stacks of legal paperwork. A coiled phone lead snakes across the screen, connecting Barbara and her granddaughter like an umbilical cord. Text on screen, in English and Pitjantjatjara, punctuates the voiceover.

In jarring opposition, Kerry’s audible crying is belied by her stoic face, rendered expressionless through the rotoscoping process. By only partially depicting the women’s images, their privacy is respected. They may present as ghosts, but it helps them retain some dignity while digging through their trauma on screen. The aesthetic reflects the utterly surreal nature of their situations.

Directed by Marieka Walsh, these scenes – almost expressionist in style – join the likes of Waltz with Bashir (Ari Folman, 2008), Last Day of Freedom (Dee Hibbert-Jones & Nomi Talisman, 2015) and Tower (Keith Maitland, 2016) as cinematic works that use animation to illustrate stories of immeasurable suffering.[7]The history of animated documentary dates back to at least 1918, with Winsor McCay’s short The Sinking of the Lusitania; see Tim Dirks, ‘Animated Films’, AMC Filmsite, <http://www.filmsite.org/animatedfilms.html>, accessed 6 February 2018. The chapters Donna and Barbara have even been released as standalone shorts, with the latter nominated in the Best Short Animation category at the 2017 AACTA Awards. Donna screened at TEDxSydney on 16 June 2017,[8]Donna, TEDxSydney website, <https://tedxsydney.com/film/donna-2017-film-program/>, accessed 6 February 2018. reinforcing the polyvalent ways true stories can be disseminated and received.

Deep listening

Also on the TEDxSydney line-up that day was emeritus professor Judy Atkinson, an expert on the transgenerational effects of trauma on Indigenous communities. Her talk, ‘The Value of Deep Listening – the Aboriginal Gift to the Nation’, holds the key to processing After the Apology. ‘There is an anger across this nation we choose not to acknowledge,’ says Atkinson in the opening moments of her address. It’s a ‘distressed discontent that is growing’.[9]Judy Atkinson, in ‘The Value of Deep Listening – the Aboriginal Gift to the Nation’, TEDxSydney, 16 June 2017, available at <https://tedxsydney.com/talk/the-value-of-deep-listening-the-aboriginal-gift-to-the-nation-judy-atkinson>, accessed 6 February 2018. Such anger, she argues, is a by-product of immeasurable – though not insurmountable – grief. She believes we can address this misery and shame, as a nation, by committing to the practice of ‘deep listening’.

Deep listening – or dadirri, to the Ngangikurunggurr people – denotes an inner stillness, silence and readiness to listen without judgement.[10]Many Aboriginal languages have words that mean similar things; see ibid. As artist and Daly River elder Miriam-Rose Ungunmerr-Baumann puts it:

Dadirri recognises the deep spring that is inside us. We call on it and it calls to us. This is the gift that Australia is thirsting for. It is something like what you call ‘contemplation’. When I experience dadirri, I am made whole again.[11]Miriam-Rose Ungunmerr-Baumann, ‘Dadirri: Inner Deep Listening and Quiet Still Awareness’, Next Wave website, 2002, <http://nextwave.org.au/wp-content/uploads/Dadirri-Inner-Deep-Listening-M-R-Ungunmerr-Bauman-Refl.pdf>, accessed 6 February 2018.

In this way, deep listening can be practised on one’s own by tuning in to the environment: heeding the breeze, the birds, whatever you find, or whatever finds you. It’s similar, in a sense, to meditation. In her TEDx talk, Atkinson describes times when she’s enacted deep (and active) listening to foster intimacy, trust and a sense of community with near-strangers. Listening is the key to healing, she says, noting that ‘with listening comes responsibility’.[12]Atkinson, op. cit.

Curiously, when After the Apology premiered at the Adelaide Film Festival in 2017, it did not close with a call to action. A series of title cards detailed positive outcomes from GMAR’s campaign: FACS has adopted the group’s guiding principles for necessary cases of child removal in New South Wales; Tighe has regained custody of her grandchildren. But the audience wasn’t then encouraged to sign a digital petition, proliferate a social-media hashtag or join a virtual ‘conversation’ online. This is atypical of contemporary social-justice documentaries, and action-oriented viewers may see it as a missed opportunity.

As Atkinson notes, however, ‘I have learned [that] my impatience, my need for action – and I’m an “action person” – is not a virtue when healing has to happen. It takes time.’[13]ibid. As Archie Roach’s bittersweet ‘Mr T’ rolls with After the Apology’s closing credits, it’s worth contemplating Atkinson’s suggestion that we begin ‘the work of deep listening […] in contemplative, reciprocal relationships’.[14]ibid.

Apologies are a dialogue. Once initiated, they require an ongoing commitment from the offender to make reparations. After the Apology illustrates the Australian Government’s lack of accountability in this area, perhaps owing to our national fear of acknowledging the trauma from which our country arose. Behrendt creates a space for non-Indigenous viewers to sit with such an abhorrent, shameful history and confront their discomfort to depths with which they will likely be unfamiliar. After the Apology is our chance to truly, deeply listen to stories about one of Australia’s worst mistakes – to ensure we don’t do it again.

http://www.pursekey.com.au/after-the-apology

Endnotes

| 1 | ‘Apology to Australia’s Indigenous Peoples’, Parliament of Australia website, 13 February 2008, <http://parlinfo.aph.gov.au/parlInfo/search/display/display.w3p;query=Id%3A%22chamber%2Fhansardr%2F2008-02-13%2F0003%22>, accessed 6 February 2018. |

|---|---|

| 2 | ‘Apology Day at Redfern’, Sydney Oral Histories, City of Sydney website, <http://www.sydneyoralhistories.com.au/stories/apology-day-at-redfern>, accessed 6 February 2018. |

| 3 | Figures cited in After the Apology. |

| 4 | ibid. |

| 5 | Larissa Behrendt, ‘Director Statement’, in Pursekey Productions, After the Apology press kit, 2017, p. 31. |

| 6 | Australian Human Rights Commission, Bringing Them Home, April 1997, available at <https://www.humanrights.gov.au/publications/bringing-them-home-report-1997>, accessed 6 February 2018. |

| 7 | The history of animated documentary dates back to at least 1918, with Winsor McCay’s short The Sinking of the Lusitania; see Tim Dirks, ‘Animated Films’, AMC Filmsite, <http://www.filmsite.org/animatedfilms.html>, accessed 6 February 2018. |

| 8 | Donna, TEDxSydney website, <https://tedxsydney.com/film/donna-2017-film-program/>, accessed 6 February 2018. |

| 9 | Judy Atkinson, in ‘The Value of Deep Listening – the Aboriginal Gift to the Nation’, TEDxSydney, 16 June 2017, available at <https://tedxsydney.com/talk/the-value-of-deep-listening-the-aboriginal-gift-to-the-nation-judy-atkinson>, accessed 6 February 2018. |

| 10 | Many Aboriginal languages have words that mean similar things; see ibid. |

| 11 | Miriam-Rose Ungunmerr-Baumann, ‘Dadirri: Inner Deep Listening and Quiet Still Awareness’, Next Wave website, 2002, <http://nextwave.org.au/wp-content/uploads/Dadirri-Inner-Deep-Listening-M-R-Ungunmerr-Bauman-Refl.pdf>, accessed 6 February 2018. |

| 12 | Atkinson, op. cit. |

| 13 | ibid. |

| 14 | ibid. |