Jaws II, Rocky II, The Pink Panther Strikes Again, and now The Empire Strikes Back … why this current spate of sequels?

One’s immediate response might be to sneer that producers, directors and writers have run out of new ideas, and so are cashing in on the old ones. Given the generally uninspiring state of today’s American cinema, there is doubtless some truth to this.

But sequels have always been with us, in one form or another. Back in the 30s, for instance, Four Daughters led to (surprise!) Four Wives; in the 40s Mrs Miniver begat The Miniver Story; in the 50s Father of the Bride was followed by Father’s Little Dividend. Television series often work on the same multiplication principle; The Nancy Walker Show came from Rhoda which came from The Mary Tyler Moore Show …

Clearly, then, there is something basic about the notion of a sequel, something which responds to the needs and the nature of commercial cinema (or television). One explanation of the phenomenon is obvious but important: getting an audience. Every film is released in the hope of securing a large audience. Often this can be a gamble, a case of hit and miss. But a sequel like The Empire Strikes Back is already assured of at least a part of the original Star Wars audience. It does not have to ‘grab’ this audience from scratch.

As proof of this one need only compare the advertising and promotion of Star Wars to that of The Empire Strikes Back. The first campaign was elaborate and expensive, attempting to counter the obvious ‘risk’ element of the film: would a modern audience, which had patronised ‘realist’ films like The Godfather, be attracted to a science-fiction/fantasy epic? But the gamble paid off. The advertising for the sequel does not need to hard-sell. All it has to do is let its waiting audience know that the film exists and is ready to be consumed. With perhaps a slight reminder of what they enjoyed in the first film, and the promise of more of the same.

Same – but different

But there is a trap in this. If a sequel is merely ‘more of the same’ it cannot hope to recapture the original audience. Hence the paradox involved in a film like The Empire Strikes Back: it must be the same film as Star Wars but it must also be a different film. To simply repeat the same situations, the same characters, the same narrative pattern would be to produce a completely redundant object. But at the same time, to make a sequel that was too different – if, say, Empire was a musical in which the entire cast had switched roles so that the heroes were now the villains and vice-versa – would be to make a film that was completely unrecognizable in relation to the original.

Take a good look at the film’s title: The Empire – a name familiar to those who have seen the first film, indeed only to them – Strikes Back – a different emphasis, a new twist, a new narrative question: is the Empire strong enough, this time, to defeat the heroes? The film would not be half as attractive if its title was The Empire Gets Beaten Again, for that would be just regurgitating Star Wars.

Clearly, the film has not abandoned its major characters or its essential subject matter, the struggle between the Empire and the Force. In fact, it is precisely because the original film based itself upon such a narrative pattern that it can be indefinitely extended: now one side has the upper hand, now the other … always the same basic situation but always a different balance of power. Only when one of the protagonists is entirely wiped out can the series end. (One can see a comparison here with, for instance, the plots in Marvel Comics, where a struggle between two groups is continued for years and years over hundreds of issues).

All films are sequels

If sequels have always been an integral part of the cinema, there is another, even broader explanation. In a sense, all films – all commercial films, at least – are sequels, for they too play this game of sameness and difference. What is a film buff if not one who forever goes to the movies knowing he or she will receive the same pleasure, re-live the same experience?

But, you will object, films have a great diversity of subjects and styles, and no individual filmgoer receives the same amount of pleasure or enjoyment from every film – quite the contrary. That is certainly true. But what we are looking for is the ‘common denominator’ across the entire range of commercial product. In a sense, a tacit contract has been signed between the film industry and the filmgoer. A film will basically be a certain kind of object; we will always know a commercial film when we see one. We run no risk of coming across something utterly unfamiliar to us.

This contract is in fact drawn up negatively, on the basis of what films will not be: boring, hard to follow, displeasurable, confusing. Commercial films tell clear stories from a clear viewpoint, they are paced and edited so that the viewer cannot slacken off or lose interest. The Empire Strikes Back would be a good example of a film made to this contract by the rules of professional filmmaking.

As filmgoers, or even film critics, we get locked into a system, placed on the conveyor belt: the next film is a sequel to the last film, sufficiently different to be interesting, sufficiently same to be reassuring. This is why, if we happen to stumble upon an ‘experimental’ or avant-garde film (by, say, Stan Brakhage or Chantal Akerman) that does not comply with the terms of the contract, which is too different, we are likely to reject it out-of-hand with a comment like “it’s not a film!” That is only because we think we know what ‘a film’ is – the only films are those which play by the rules. And perhaps Metro, by concentrating mainly on conventional short and feature films, helps to reinforce this blinkered attitude (please take note of the provocation!)

Genre films as sequels

“Preconstruction involves the ready-made positions of meaning that a film may adopt … genre is a major factor of preconstruction” (Stephen Heath).

What Heath, one of the writers in the progressive film journal, Screen, is pointing to here is the way genre films also, and especially, create a desire in us to see the ‘same’ film over and over again, with the necessary amount of difference or variation each time. Someone who is a fan of westerns, or science-fiction films, knows roughly what he/she is going to encounter in any particular instance of the genre: in this sense the films are ‘preconstructed’, ready-made.

In westerns, for instance, a basic generic element is the gunfight. Thus many westerns declare their generic identity – and thus claim their audience – by flaunting this element in their very titles: Gunfight at the OK Corral, The Gunfighter, Guns in the Afternoon, Forty Guns … If a western promised such an element but then did not deliver, it would risk frustrating and alienating a major part of its stable audience. (Of course, many ‘modern’ westerns, such as those by Arthur Penn, for instance Little Big Man or The Missouri Breaks, play precisely upon this kind of frustration.)

I am not saying that every conventional genre film follows the same fixed pattern, has the same characters and situations. Genres must be thought of as ‘pools’ of material: an individual genre film picks out some elements and not others to work with, and arranges them in particular ways. This goes for the science-fiction genre as for the western; The Empire Strikes Back could be related, for example, to these three generic elements, to judge how concerned it is with each:

1. Other worlds – space travel.

“‘SF’ is a genre whose strength comes from its imaginative powers, its ability to create societies in which alternative laws of action and behaviour can be displayed.” (Terry Curtis Fox). Much science-fiction is based on the question: what is beyond earth? What happens once we pass out of its limits? Earth stands for safety, for what is known and can be controlled. Space travel is both literally and figuratively a ‘leap into darkness’, and hence the film titles which stress this voyaging outwards, the leaving behind of earth: 2001 A Space Odyssey, Twenty Million Miles To Earth, Destination Moon.

Thematically, films concerned with this aspect of SF often deal with the loss of earth-bound identities and social structures once outer space and/or other civilisations are encountered – Dark Star, for instance, in which the astronauts lose their sanity, or 2001. Relevant in this regard is the role that the family, and particularly the presence of a father-figure, play in Star Wars and Empire. Is the family-structure questioned, reaffirmed, replaced by another structure?

2. The Alien.

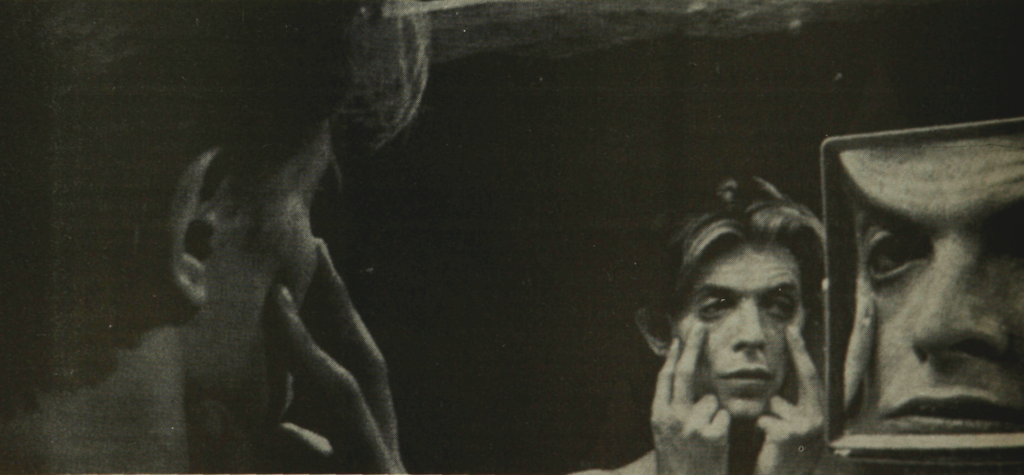

What has fascinated and motivated SF creators for a long time has been the idea of imagining a person utterly different from an earth-defined human being, someone ‘other’ than the norm to which we are acquainted. Films in this category include Alien, The Man Who Fell to Earth and The Thing.

Aliens are open to wide interpretation. Often they are simply figures of evil, the ‘villains’ that can be opposed to the earthling heroes, such as in Star Wars. But they can also stand for other social systems on earth itself – Communism for instance, in Invasion of the Body Snatchers (both old and new versions). Or, to take a Freudian line, they can symbolise repressed sexual drives (David Bowie’s bisexual alien in The Man Who Fell to Earth being the outstanding example of this).

3. Technology.

Science fiction’s attitude towards technological progress has always been ambivalent. On the one hand, technology opens up the universe and makes us its masters; man can live in harmony with the products of technology (i.e. C3PO and R2D2 in Star Wars). On the other hand, technology rampant can overwhelm and destroy man, escaping from our control – 2001, The Andromeda Strain, Westworld.

This problem takes on a new twist in Empire, for the film is itself a product of super technology on the production level (effects, sets, gadgets). The very existence of the film, plus its popularity, imply a celebration of space age advances, whatever the explicit message of the film’s content.

Why all these detours away from the film itself? While doubtless any individual film can and should be discussed in its own terms, I want to stress here that a film is also con-textual and inter-textual – in other words that it has a clear and recognisable place within the domain of commercial cinema, and that it borrows from many films in many ways. For this is not only a question of what goes to make up The Empire Strikes Back as a film. It is also a question of why we feel we want to see it, what prompts us to pay money to see it.

WORKBOOK

1. Before seeing the film: What do you think might happen – how will the Empire strike back? How will the film end? (compare your guesses with the film once you have seen it).

2. Also before seeing the film: What did you like in Star Wars that you would like to see more of? What did you dislike that you think should be left out of the sequel?

3. Look at the newspaper advertising for Empire. How much does it tell you about the film? How much does it presume you already know?

4. Do you think the film is ‘professional’, well-made? What kinds of things make it professional? What would an unprofessional film look like?

5. Try to list as many ‘typical’ science fiction elements as you can, from your knowledge of both films and books. How many of these appear in Empire? How many do you think could be fit into a single film?

6. What is the film’s attitude toward technology and space travel – are these things safe or threatening?

7. Can you find elements from other genres (e.g. fairy tales, war films) apart from SF in the film?

8. Discuss the ‘villains’ in this film. Are they like the baddies in other sorts of films – westerns, war films, etc? Can the hero and heroine also be related to other films in this way?

9. Imagine you had to plan the third film in the series. In what direction would you take the story? What would you retain from the first two films, and what would you change?

10. If you want to sample unconventional, ‘rule-breaking’ films, consult the National Library catalogue, which contains a comprehensive selection of avant-garde cinema, including Stan Brakhage’s films.