Raging Fire (2021), the recent Hong Kong martial-arts police actioner starring Donnie Yen Ji-dan, is something of a bitter pleasure. The film was only released in July last year, almost two years after shooting wrapped. During that period, its director, Benny Chan Muk-sing, died of cancer at the age of fifty-eight.

While few would claim that Chan was a major director on the level of, say, Johnnie To Kei-fung or Tsui Hark, he could be relied on for the kind of solid, entertaining action films on which Hong Kong cinema’s reputation is based. His career started in television at TVB, the station that the Shaw Brothers film studio transformed itself into, and went on to include features such as Big Bullet (1996), Gen-X Cops (1999), New Police Story (2004) and The White Storm (2013).

Raging Fire is the type of film Hong Kong used to turn out with seemingly effortless mastery. The straight-arrow cop and his team are hampered by a corrupt, pusillanimous bureaucracy as they go up against a group of baddies as stylish as they are ruthless. Cars, motorbikes, explosives, assault rifles, fists, legs and, yes, even a statue of the Virgin Mary become weapons to be deployed with an exuberant lack of restraint. Much pain is inflicted before good triumphs and bad is punished, in line with mainland China’s censorship guidelines.

But then, instead of the customary blooper reel we expect from Hong Kong films, Raging Fire’s end credits feature a black-and-white tribute to Chan. While watching the film alone in an empty cinema, it seemed appropriate to yield to a pessimistic mood and ask: is this the end? After all, we’re living through major realignments of Hong Kong social fabric, the international order, the prospects of a post-pandemic cinema and, perhaps most importantly, Australia’s relationship to China. We may well be bidding goodbye to more than just Chan.

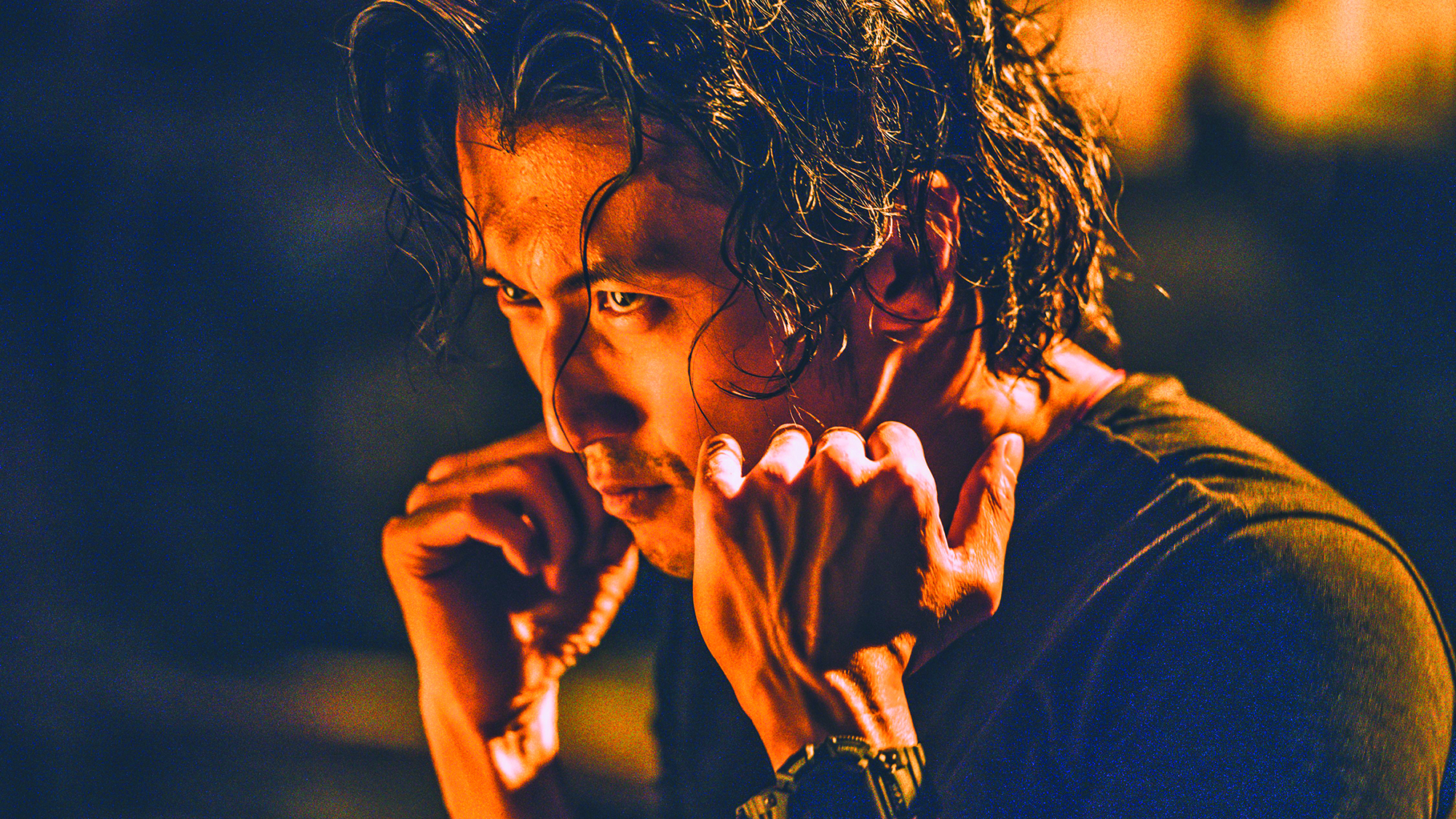

Hong Kong’s is a film industry built around headline actors, but, like Bollywood, it has been finding it hard of late to come up with a new generation of stars. Yen is fifty-nine, and Raging Fire co-star Nicholas Tse – once the rebellious youth of Hong Kong cinema – is now in his forties; he is better known these days as a celebrity chef on the telly. Andy Lau Tak-wah just turned sixty, and Jackie Chan (as if anyone cared anymore) is sixty-eight and lost amid the wastelands of commercial mainland cinema and the politics of its masters.

Hong Kong, with a population under a third the size of Australia’s, has always relied on other markets for its audience – most notably Taiwan, then Japan, and lately mainland China, which is now the main game with other overseas markets largely gone. Although Raging Fire, like many of Benny Chan’s films, bears the production logo of Emperor Motion Pictures (a film company spawned, in inimitable Hong Kong fashion, by a jewellery business), it had a variety of mainland co-producers. The film has grossed over US$205 million worldwide, with an overwhelming US$202 million of that total coming from China. (In Australia, it managed a mere US$57,000.)

A few years ago, Chinese film companies were throwing money around like drunken sailors. But now Chinese money is increasingly being spent on the mainland as it develops its own stars and directors who are happily – if seldom competently – making their own blockbusters. Commercial Hong Kong directors are more likely to be found these days working on the mainland. The latest monsters at the Chinese box office are the Korean War movie The Battle at Lake Changjin (Chen Kaige, Dante Lam & Tsui, 2021) – which boasted impeccable Communist Party credentials and took in nearly US$900 million at the domestic box office – and its sequel, The Battle at Lake Changjin II (Tsui, 2022).It is significant that two of these films’ three directors, Tsui and Lam, are Hongkongers. And earlier last year, another Hong Kong–based director, Andrew Lau Wai-keung – of Infernal Affairs (2002) fame – had a considerable hit with Chinese Doctors (2021), a film mythicising the valiant efforts of Wuhan’s medical staff to contain COVID-19.

These predictions that Hong Kong cinema will be swallowed whole by the People’s Republic of China have been around for a while – though, given the events of the last couple of years, perhaps we should be talking about the end of Hong Kong, rather than just the end of Hong Kong films. One of the things that drew many of us to the city and its cinema was that it was a place with the space to be radically different. However, as we head into the new Cold War – at least, we have to hope it will stay cold – there seems decreasing space for that difference. Contrary to international hopes of economic liberalisation leading to increasing political liberalisation, Xi Jinping’s government is intent on holding together a country that it views as liable to fall apart along regional, ethnic or religious fault lines, or through the excesses of the market forces that have been unleashed.

Hong Kong does not have a long tradition of democracy, but the protest movement of the past couple of years have led to societal polarisation. The economic transformation of China has been felt very unevenly in Hong Kong: a younger generation sees their opportunities receding as property values skyrocket and their neighbourhoods are priced out of their capacity. Yet while our media outlets tend to report only this side of things, there are many others in the city who respond to the nationalist appeal of the mainland government, and who see that the best way to stability and prosperity is to not antagonise the dominant political forces.

So, perhaps, we should instead be talking about the end of Hong Kong screen culture. Given recent events, commercial genre films start to look rather conservative in filling the streets with fantasy gunfights rather than the protest movement, while their stars (such as Yen) post National Day messages on social media. Young filmmakers, who have less to lose, are less likely to come out of TVB now and more likely to come out of the universities, where lurk political protest and art cinema. Cannes last year screened Revolution of Our Times (Kiwi Chow, 2021), a low-budget documentary sympathetic to the protest movement. Don’t expect to see a film like that anytime soon at the Hong Kong International Film Festival (HKIFF) – state-supported cultural institutions, like movie stars, have to know which side their bread is buttered on.

Of course, those who proclaim the end of things in cinema have a way of looking silly very quickly. In bidding goodbye to Chan, and goodbye to the Hong Kong cinema of my youth, maybe I’m just saying goodbye to my youth – and while grumpy old fanboys are left with their DVD collections, something new is always coming into being. Let us hope that, for a city and a cinema enduring precarious times, endings can yet turn into beginnings.