Sometime in the twenty-first century, photographer Sandy Edwards pores over a contact sheet containing multiple variants of an image captured decades earlier: a group shot of thirty or so women gathered in the New South Wales bush. The occasion, we’re told, was a discussion weekend organised in 1978 by the Feminist Film Workers, a collective spun off from the Sydney Women’s Film Group, made up in turn of members of the larger Sydney Filmmakers Co-operative (SFC). On the day, Edwards says, it took a while to agree on an appropriate pose – ‘who should stand where, who should be in the middle, who should be on the sides’.

This debate over what face to turn to posterity is recounted around an hour into John Hughes and Tom Zubrycki’s documentary Senses of Cinema (2022), a valuable if necessarily partial survey of the alternative filmmaking practices that flourished in Australia over the crucial period from the late 1960s to the mid 1980s. In this context, Edwards’ memories take on a reflexive significance beyond her own immediate intentions – a trick that is characteristic of Hughes, a less straightforward filmmaker than he first appears when it comes to crafting polysemic essays from disparate materials old and new. Senses of Cinema itself is another group portrait, featuring some of the same individual subjects as Edwards’ photos; though decisions about whom should be centred or sidelined are, in this case, out of their hands.

How should Senses of Cinema be framed in turn? We could set it alongside Mark Hartley’s rambunctious Not Quite Hollywood (2008) as a polemical alternative to orthodox critical accounts of the so-called Australian new wave.[1]The one interview subject to appear in both Not Quite Hollywood and Senses of Cinema is the droll producer Richard Brennan, who recalls his involvement with Mad Dog Morgan (Philippe Mora, 1976) in the former documentary and The Love Letters from Teralba Road (Stephen Wallace, 1977) in the latter. Or we could position it as the latest of Hughes’ deep dives into the local archive, following Film-Work (1981) and Indonesia Calling: Joris Ivens in Australia (2009). Like these earlier Hughes works, Senses of Cinema is artfully made but qualifies as film history more than film criticism, while pursuing a political goal above all: not to champion an alternative pantheon of Australian filmmakers or even a specific mode of filmmaking, but to document the existence of spaces where various modes could coexist and sometimes converge.

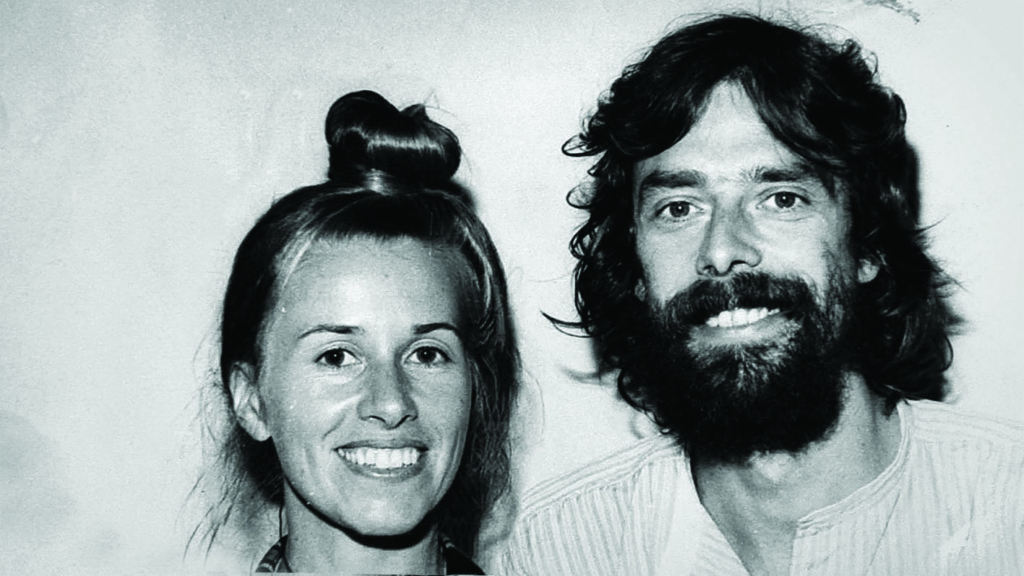

Indeed, Hughes and Zubrycki might be said to have renewed the notion of convergence in their own way, as first-time co-directors coming from somewhat dissimilar though comparably lengthy solo careers (their combined filmmaking experience totals around a century). It’s tempting to assume that Hughes took the lead in this, given that he receives sole script credit and that Senses of Cinema fits snugly into his oeuvre, whereas affinities with Zubrycki’s observational documentaries such as Molly & Mobarak (2003) are much less apparent. Still, here we have two politically engaged Australian non-fiction filmmakers of the same generation who have weathered changing fashions while maintaining a focus on the socially marginal – in short, there’s no reason to suppose this wasn’t a genuine meeting of minds.

Regardless, Hughes and Zubrycki’s approach is very much a pluralist one, as is signalled in their title – and, before we go any further, it may be worth spelling out that Senses of Cinema the documentary has no direct link with the venerable online film journal of the same name, founded in Melbourne in 1999.[2]Full disclosure: I was once a co-editor. See Senses of Cinema, <https://www.sensesofcinema.com/>, accessed 30 October 2022. Still, those in the know may perceive in its title a nod to the continuity and diversity of grassroots Australian film culture across the second half of the twentieth century and beyond, with ‘culture’ defined in a manner that encompasses not just the making of films but equally their distribution and reception.

The specific roots of Ubu lay in the libertarian/anarchist tradition of the Sydney Push; both the Sydney and Melbourne co-ops inherited a modified version of that ethos, relying ultimately on government funding but allowing filmmakers a degree of independence.

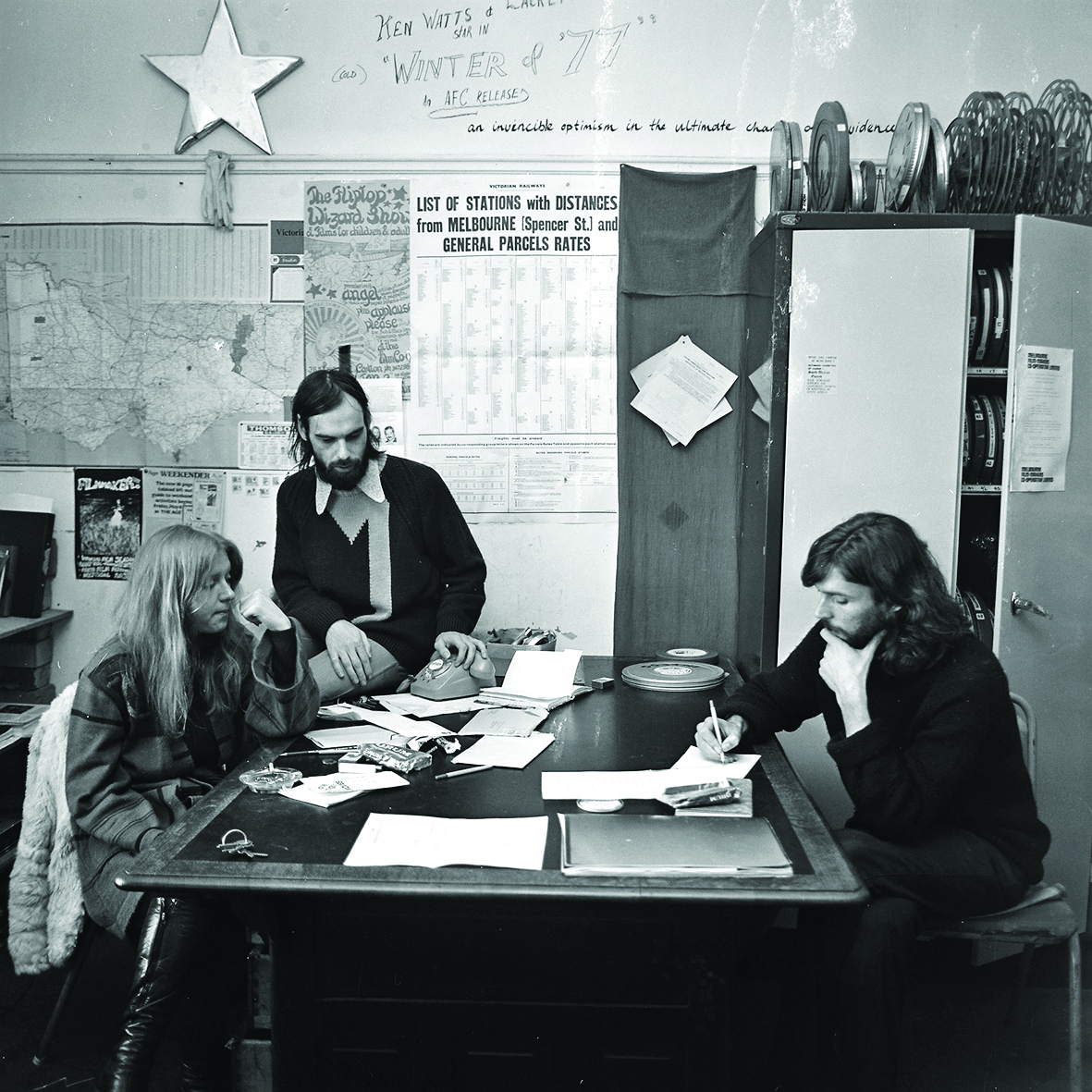

No culture can survive without institutions, and Senses of Cinema the film presents itself as a history of two such institutions in particular: the SFC, which emerged around 1970 from the ashes of the ‘underground’ collective Ubu Films; and the shorter-lived Melbourne Filmmakers Co-Op, founded the same year.[3]For more on this history, see Peter Mudie, Ubu Films: Sydney Underground Movies 1965–1970, University of New South Wales Press, Sydney, 1997, pp. 13–7. As Hughes points out in a useful 2015 article published in Senses of Cinema (the journal), these were the most prominent Australian filmmakers’ co-operatives – though far from the only ones – and part of a movement then gaining pace around the world. As the article also notes, the specific roots of Ubu lay in the libertarian/anarchist tradition of the Sydney Push; both the Sydney and Melbourne co-ops inherited a modified version of that ethos, relying ultimately on government funding but allowing filmmakers a degree of independence from both the commercial film industry and the state.[4]John Hughes, ‘A Work in Progress: The Rise and Fall of Australian Filmmakers Co-operatives, 1966–86’, Senses of Cinema, no. 77, December 2015, <https://www.sensesofcinema.com/2015/australian-film-history/australian-filmmakers-co-operatives/>, accessed 28 October 2022.

What did these co-ops, sustained by paid staff but also by the efforts of their members, actually do? They brought filmmakers together, allowing them to pool equipment and resources. They mounted festivals and regular screenings at their own venues (primarily on 16mm film, then the default ‘alternative’ medium). They maintained film libraries, renting out prints to educational institutions and other interested groups. They facilitated the sale of prints. They organised conferences. They offered training workshops. They lobbied funding bodies. They published journals that spread the word about all this activity while serving as broader platforms for debate and criticism.[5]See John Cumming, The Films of John Hughes: A History of Independent Film Production in Australia, Australian Teachers of Media, St Kilda, Vic., 2014, pp. 19–40; Barrett Hodsdon, Straight Roads and Crossed Lines: The Quest For Film Culture in Australia from the 1960s?, Bernt Porridge Group, Shenton Park, WA, 2001; Hughes, ibid.; Mudie, op. cit.; Lena Lester, ‘Melbourne Filmmakers Co-operative Ltd.’, Metro, no. 35, Autumn 1976, p. 22; Jennifer Stott, ‘Independent Feminist Filmmaking and the Sydney Filmmakers Co-Operative’, in Annette Blonski, Barbara Creed & Freda Freiberg (eds), Don’t Shoot Darling! Women’s Independent Filmmaking in Australia, Greenhouse Publications, Richmond, Vic., 1987, pp. 118–126; Albie Thoms, ‘Ten Years of the Sydney Filmmakers Co-op – Part One: The Beginnings’, Filmnews, April 1976, pp. 5–9; Thoms, ‘Ten Years of the Sydney Filmmakers Cooperative – Part Two,’ Filmnews, December 1976, pp. 16–22; and Marek Zaylor, ‘Melbourne Filmmakers Co-op’, Filmnews, July 1976, p. 11. In short, they opened up possibilities beyond those available to individuals going it alone – including, in some cases, the possibility of making the leap into the mainstream, though this was far from a universally shared dream.

Senses of Cinema does not purport to cover all this activity in detail, but an impressive amount is packed into less than ninety minutes, including a wide range of clips interwoven with present-day commentary from old hands. That is, ‘present-day’ very loosely speaking, since some of this material was evidently shot long before the film’s 2022 premiere: one of the first voices we hear belongs to Sydney co-op manager turned industry player Phillip Noyce, seen on an LA studio lot directing one of the first episodes of the 2011–2015 US network TV series Revenge, which a decade on must be just about due for a reboot. Marking time between set-ups, Noyce fondly looks back to the life-changing day when, as a teenager, he first caught sight of an Ubu poster; from there, we jump to Ubu co-founder Albie Thoms presumably at his home in Sydney, still in his trademark hippie cowboy regalia (crimson shirt, black waistcoat) in what must have been one of his final interviews before his death in 2012.

All this forms part of a montage that, like much of the film, is organised dialectically, in a manner whose full meaning depends on the viewer’s knowledge of facts not spelled out – in this case, the contrast between Noyce’s and Thoms’ respective career trajectories, especially from the 1980s on. A different dialectic is spelled out when Thoms summons a fond memory of his own: the Ubu screening when his abstract, handmade film Bluto (1967) was shown along with the agitprop newsreel President Johnson’s Visit (Kit Guyatt & Christopher Cordeaux, 1966).[6]The latter film was primarily known by its alternative title, Vietnam Report, at the time of the screening. As Thoms recollects it, these weren’t just items on the same bill but literally projected side by side, merged into a single ad hoc two-screen work predestined to blow minds: ‘The two seemed to be in absolute synchronisation, the flickering colour reflecting the agitation of the protesters.’ To illustrate the point, he holds both hands out in front of himself, cueing Hughes and Zubrycki to re-create the original juxtaposition before our eyes: surging bodies on the left, dancing squiggles on the right.

Thus reconstituted, the twinned image functions like a rebus, signifying a moment when separate forms of radical cinema were felt to be in harmony. Already, though, the documentary has hinted at just how fleeting this harmony would be. A five-second clip from the underground ‘classic’ Boobs-a-Lot (Aggy Read, 1968) is enough to indicate that the macho Ubu mindset was on a collision course with second-wave feminism – prefiguring one central strand of Senses of Cinema, which tracks the rise of feminist (and queer) filmmaking within the co-ops to the occasional discomfort of at least some of the old guard. Another, sometimes intertwined, strand deals with what Hughes has termed ‘the emergence of Indigenous authorship’,[7]Hughes, op. cit. initially for the most part in films signed by white directors – one example being Noyce’s fascinating if not wholly coherent Backroads (1977), in which Indigenous activist Gary Foley agreed to star on the condition that he could ignore the scripted dialogue and supply his own.

Viewing all this through a modern identity-politics lens, it’s hard to bracket off the irony that Senses of Cinema is itself a film made by a couple of old white guys; Hughes and Zubrycki seem as aware of this as anyone, which may account for some otherwise curious aspects of their approach. Both were actively part of the co-op movement from the mid 1970s on – Hughes in Melbourne, Zubrycki in Sydney – and, on one level, Senses of Cinema acknowledges this connection with perfect candour: clips from their works are woven into the montage, and their names are spoken by interviewees. Yet while the film does without a ‘voice of God’ narrator, it equally eschews any overt first-person perspective; it comes as a mild shock when director Peter Tammer, reminiscing about the early days of the Melbourne co-op, addresses his unheard off-camera interlocutor as ‘John’. It’s as if Hughes and Zubrycki were conscientiously declining to take ownership of the co-op story – although Senses of Cinema in its entirety is their version of that story, and can’t be otherwise.

This leaves a good deal open to speculation, at least for viewers (like this writer) who can’t themselves claim insider status. All up, the Sydney co-op gets significantly more screen time than the Melbourne one. That may not be wholly unreasonable, given the abrupt 1977 demise of the latter, marking the end of an era (if not the end of independent Melbourne filmmaking as such). Harder to parse, though, is the specific logic dictating who gets a guernsey and who doesn’t, especially when it comes to the Melbourne scene. Of the Melbourne co-founders, we hear from Tammer and Fred Harden but not from Bert Deling, even though a young Hughes worked on Deling’s radically self-negating Dalmas (1973).[8]See Cumming, op. cit., p. 31. Hughes described the experience as ‘extraordinary’, and has elsewhere called the film ‘remarkable’. See Hughes, ibid. Avant-gardists such as Corinne Cantrill and Michael Lee, who both withdrew from the Melbourne board after 1972,[9]Hughes, ibid. likewise fail to make the cut – though the name ‘Cantrill’ flashes past on the typed minutes of a board meeting, visible for all of three seconds.

Clearly, choices had to be made; but, for just that reason, it doesn’t hurt to cross-reference the picture offered by Senses of Cinema with other sources. One such source might be John Cumming’s invaluable 2014 study The Films of John Hughes: A History of Independent Screen Production in Australia, which records that the Melbourne co-op in the early 1970s was to a degree internally split, with Hughes as a member in no doubt about where he stood: his focus was, as Cumming puts it, on ‘the political use of film’, while he remained ‘skeptical about experimental cinema associated with the American avant-garde’.[10]Cumming, op. cit., pp. 32–4. Cumming himself cautions against making too much of this;[11]ibid., p. 34. and, certainly, there’s been ample time for Hughes’ thinking to evolve in the decades since. But, just as certainly, there’s some relationship between Hughes’ and Zubrycki’s firsthand experiences of the co-op era and how they view that period in hindsight – and not much about that relationship can be gleaned from Senses of Cinema, at least not without a good deal of decoding.

As for lessons that might be drawn for the future, here the film is a little more explicit, offering a few options via different interviewees. As a one-time co-op member turned new-media artist, Helen Grace argues that, in the online realm, the co-op logic of self-distribution has triumphed: getting your stuff out there without waiting for permission has become the new normal. On one level, this is inarguably true – but also perhaps not all that meaningful, given that the technological, cultural and economic challenges of holding screenings in rickety fire-hazard theatrettes or dispatching film prints to workers’ discussion groups remain several universes away from those of trying to get noticed on TikTok.

More persuasive is the documentary’s argument that the strength of the co-op movement – in this, very much unlike the internet – sprang from its creation of a degree of solidarity between people with little in common apart from being, in one way or another, ratbags: that is, true believers in projects inimical to the mainstream. Filmmaker and scholar Jeni Thornley tells the peace-and-love version of this tale, in which the mingling of avant-gardists, feminists and social-documentary types created a ‘broad palette’ of approaches that, to an extent, became the common property of all. Stephen Wallace, now known as the director of features such as Stir (1980) and Turtle Beach (1991), puts it somewhat differently, stressing the bracing effect of ongoing clashes between camps or individuals who never did see eye to eye. ‘You had to cope with their arguments. They challenged you all the time. You tried to challenge them.’

More persuasive is the documentary’s argument that the strength of the co-op movement sprang from its creation of a degree of solidarity between people with little in common apart from being, in one way or another, ratbags.

Thoms, for one, grew sick and tired of being challenged, judging by his expression as he recalls the ‘neo-Marxist’ do-gooders who in the end got the better of him: the hurt grin of a kid who took his cricket bat and went home. Still, lurking beneath the air of grievance might be a touch of grudging respect for any kind of bolshie, bloody-minded attitude, even coming from the other side. Probably, a Thoms of today would have no reason to be in the same room with the modern equivalent of a feminist film collective; probably, in many ways, that’s for the best. But these were different times, when we weren’t all nodes in a global distribution network by default, and alliances and enmities alike were forged in the face of the sheer bloody difficulty of getting anything done.

None of it, of course, was ever just about the movies. If you hunt online, many of the titles namechecked in Senses of Cinema are more readily available than ever before, free on YouTube or streamable from other platforms at no great cost – something to be grateful for, no question. But, however miraculously preserved these may be, all you’re getting are traces, afterimages of the thing that was, the irrecoverable past itself. Mostly, Hughes and Zubrycki are too high-minded for gossip, but a moment as funny as anything in Not Quite Hollywood supplies at least a glimmer. ‘There was a lot of free love and swapping of partners,’ pioneering documentarian and cinematographer Martha Ansara recalls of the co-op milieu, before we cut to the white-haired, mild-mannered Tom Cowan musing on the same theme: ‘Well, I think it was terrifically good at cross-fertilisation.’

As if mentally playing back what he’s just said, Cowan scrambles to clarify: ‘You know, meeting all those people that, um, came around …’ The thought trails off, and, rather than dig himself any deeper, he settles for affirming that these were, indeed, good times. At least, good for the most part: he wasn’t so happy about that one party where the punch was spiked with LSD. The culprit’s name is bleeped out, but watching the film at the Melbourne International Film Festival with a mostly older crowd, I sensed some stifled giggles. Sometimes, evidently, you just had to be there.

https://sensesofcinemafilm.com.au/

Endnotes

| 1 | The one interview subject to appear in both Not Quite Hollywood and Senses of Cinema is the droll producer Richard Brennan, who recalls his involvement with Mad Dog Morgan (Philippe Mora, 1976) in the former documentary and The Love Letters from Teralba Road (Stephen Wallace, 1977) in the latter. |

|---|---|

| 2 | Full disclosure: I was once a co-editor. See Senses of Cinema, <https://www.sensesofcinema.com/>, accessed 30 October 2022. |

| 3 | For more on this history, see Peter Mudie, Ubu Films: Sydney Underground Movies 1965–1970, University of New South Wales Press, Sydney, 1997, pp. 13–7. |

| 4 | John Hughes, ‘A Work in Progress: The Rise and Fall of Australian Filmmakers Co-operatives, 1966–86’, Senses of Cinema, no. 77, December 2015, <https://www.sensesofcinema.com/2015/australian-film-history/australian-filmmakers-co-operatives/>, accessed 28 October 2022. |

| 5 | See John Cumming, The Films of John Hughes: A History of Independent Film Production in Australia, Australian Teachers of Media, St Kilda, Vic., 2014, pp. 19–40; Barrett Hodsdon, Straight Roads and Crossed Lines: The Quest For Film Culture in Australia from the 1960s?, Bernt Porridge Group, Shenton Park, WA, 2001; Hughes, ibid.; Mudie, op. cit.; Lena Lester, ‘Melbourne Filmmakers Co-operative Ltd.’, Metro, no. 35, Autumn 1976, p. 22; Jennifer Stott, ‘Independent Feminist Filmmaking and the Sydney Filmmakers Co-Operative’, in Annette Blonski, Barbara Creed & Freda Freiberg (eds), Don’t Shoot Darling! Women’s Independent Filmmaking in Australia, Greenhouse Publications, Richmond, Vic., 1987, pp. 118–126; Albie Thoms, ‘Ten Years of the Sydney Filmmakers Co-op – Part One: The Beginnings’, Filmnews, April 1976, pp. 5–9; Thoms, ‘Ten Years of the Sydney Filmmakers Cooperative – Part Two,’ Filmnews, December 1976, pp. 16–22; and Marek Zaylor, ‘Melbourne Filmmakers Co-op’, Filmnews, July 1976, p. 11. |

| 6 | The latter film was primarily known by its alternative title, Vietnam Report, at the time of the screening. |

| 7 | Hughes, op. cit. |

| 8 | See Cumming, op. cit., p. 31. Hughes described the experience as ‘extraordinary’, and has elsewhere called the film ‘remarkable’. See Hughes, ibid. |

| 9 | Hughes, ibid. |

| 10 | Cumming, op. cit., pp. 32–4. |

| 11 | ibid., p. 34. |