High Ground (Stephen Maxwell Johnson, 2020) is an arresting and immersive film that uses the genre of the western to bring Australia’s past to life. It has been a long time coming for Johnson; while his journeyman career has included music videos and television work, he has not directed a feature film since 2001’s Yolngu Boy. High Ground has been well worth the wait, however. Its international premiere at the Berlin International Film Festival in February 2020 yielded international sales to Playtime in Europe, Samuel Goldwyn Films in the United States and Madman locally, shortly before global film exhibition ground to a shuddering halt. High Ground’s COVID-safe gala at the Adelaide Film Festival in October 2020 had the air of a truly special occasion: David Gulpilil, Rolf de Heer and Jack Thompson were among the guests to take their seats in the audience, while producer/actor Witiyana Marika and the film’s extended cast performed a ceremonial welcome. Johnson, with some understatement, explained that ‘the film will do the talking’. A work born of genuine collaboration and exchange, High Ground has much to say, and will doubtless be the most discussed Australian film of the year once it has received its local theatrical release in January 2021.

The film opens with a soaring aerial shot over spectacular Arnhem Land scenery, immediately transporting us to a landscape that feels prehistoric, even as the on-screen title places the narrative in 1919. At the centre of the film is two men. We are introduced to the first, Gutjuk, as a child (Guruwuk Mununggurr) as he watches his family hunt wallabies. The harmonious idyll of silent feet on the forest floor is contrasted with the crashing intrusion of horses. The second, Travis (Simon Baker), is a sniper returned from World War I, now working as a Northern Territory police officer. Travis, too, is first seen at a distance, observing Gutjuk’s family through the crosshairs of his rifle, providing cover as his team advance on the waterhole, responding to complaints of purloined livestock. The mirroring of the watcher and the watched establishes the bond that will subsequently develop between the two men. When confrontation breaks out on the ground, Travis’ offsider Eddy (Callan Mulvey) loses his nerve and opens fire, and the scene turns into a bloodbath, with the officers indiscriminately massacring the Indigenous family. Travis demonstrates his own autonomous moral code by wading into the waterhole to rescue the surviving Gutjuk – much to the disapproval of Eddy.

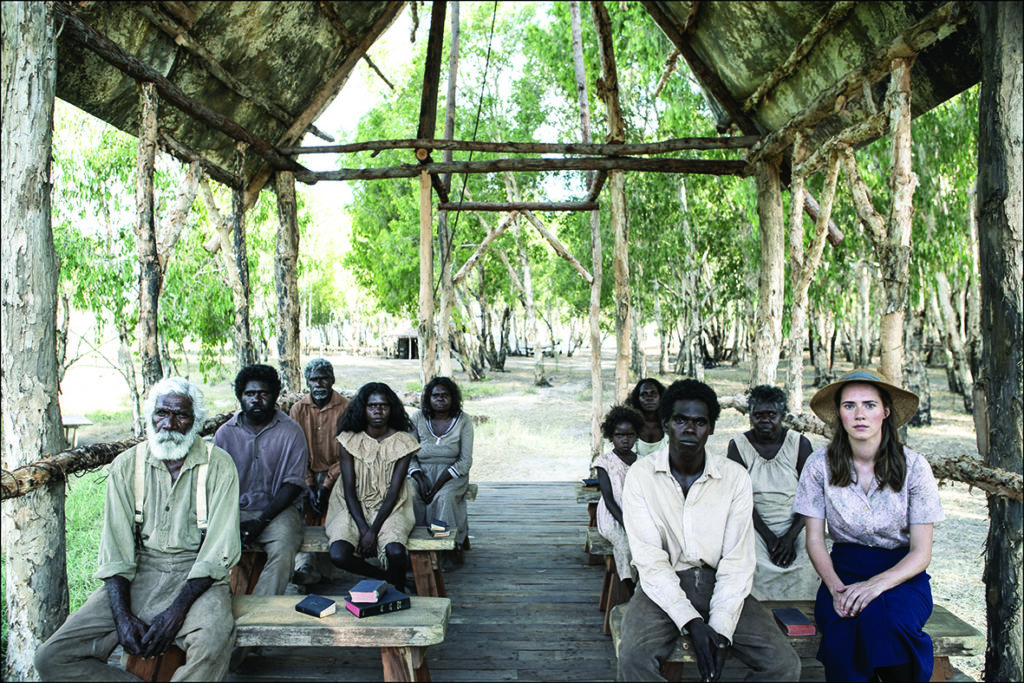

The plot resumes twelve years later. Gutjuk (played as an adult by Jacob Junior Nayinggul) has been raised under the anglicised name Tommy, and is living as a station hand at the East Alligator River mission reserve with the compassionate Claire (Caren Pistorius) and her brother, pastor Braddock (Ryan Corr). Travis and Eddy have maintained a mutual code of silence over their complicity in the massacre; the past resurfaces, however, when they are summoned by their commander, Moran (Thompson), who brings warnings that a ‘wild mob’ is wreaking havoc across the country, killing livestock and burning stations. The leader of these outlaws is Baywara (Sean Mununggurr), an uncle of Gutjuk’s who is rumoured to be another survivor of the massacre. Moran knows that there was more to this bloody incident than was officially reported, and dispatches Travis to quash this potential resistance before the distant commissioner begins asking questions.

Travis surprises Eddy by eschewing the latter’s assistance on this mission (‘I won’t make the same mistake twice’), and instead enlists Gutjuk as his tracker, assuring the young man that he intends to bring his uncle in alive, and will show him the mercy that will otherwise be shunned if they fail in their mission. Gutjuk accompanies Travis, but harbours secret plans to defect and turn Travis over to Baywara.

In a thematically resonant scene, Travis and Gutjuk begin to develop a shared code of respect. As a show of trust, Travis hands his rifle over to Gutjuk and teaches him how to shoot. Gutjuk is frightened by the gun, but willingly enters this ritual of masculine instruction after Travis explains, ‘When you’ve got the high ground, you control everything.’ By returning to point-of-view shots through the rifle’s sight, the film reiterates one of its central themes: the power inherent within the gaze. This is reinforced visually throughout the film, particularly when the world is viewed down the barrel of a gun, or through the lens of a coloniser’s camera: each a technological intervention that can violently recast the narratives of history.

The film opens with a soaring aerial shot over spectacular Arnhem Land scenery, immediately transporting us to a landscape that feels prehistoric, even as the on-screen title places the narrative in 1919.

The film establishes the power of perspective in key exchanges. When Travis is taken captive, he is depicted in wide-shot framings, emphasising his disempowerment and underscoring his status as an interloper in a land that is not his own. Later, in the film’s centrepiece, elder Dharrpa (Marika) and police commander Moran enter into tense negotiations over which law will determine Baywara’s fate. Their faces fill the frame in extreme close-up, addressing the camera directly as they argue for their respective cultures of justice. Each claims sovereignty and the rule of law within this land; the irreconcilability of their positions sets the narrative on its tragic path.

Johnson invokes a series of structural repetitions that gain resonance throughout the film. Dharrpa and Moran are both patriarchal authorities, attempting to shape the futures of their respective charges, Gutjuk and Travis. For Travis’ part, he has witnessed the horrors of war, and carries these memories with him as he attempts to fulfil a mission that he knows, on some level, is impossible. Gutjuk, too, is caught between cultures, between his mission upbringing and the ancestral land, evident in his two names. Even among his people, the path forward is not clear. Dharrpa urges him to be one with nature and embrace his traditional way of life – ‘to listen to the wind and the sky’, and to ‘walk softly’. Meanwhile, the renegade Gulwirri (Esmerelda Marimowa) explains how she defied the repressions of her own mission upbringing, telling Gutjuk, ‘Your anger is all you have.’

In her limited screen time, Gulwirri is one of the most striking characters in the film, bluntly piercing the posturing of others, and spurring Gutjuk towards acts of guerilla resistance. Her character evokes the indomitable spirit of Kameraigal leader Barangaroo, as she is characterised in Inga Clendinnen’s history of early contact Dancing with Strangers. Indeed, the film’s peripheral characters are among its most memorable: sunbaked police officer Walter (Aaron Pedersen), for instance, brings some bedraggled humour to the film; and through Thompson’s commanding performance, Moran reveals the implacable moralism undergirding the colonial project, rationalising its inevitable brutality as the work of ‘bad men […] clearing the way for others to follow’. Thompson’s presence in this film is all the more remarkable given that, throughout the location shoot, he was receiving dialysis from the non-profit Purple House remote health service after each day’s filming wrapped, as revealed in the 2019 Australian Story episode ‘Back on Track’.[1]See ‘Back on Track’, Australian Story, available at

<https://www.abc.net.au/austory/back-on-track/10811402>, accessed 2 November 2020.

As for Baker, High Ground cements his symbolic homecoming after his directorial debut and starring turn in Breath (2017), following the better part of two decades in American television. His character of Travis is something of a cipher for the film’s non-Indigenous audience, and there’s an air of revisionism in his and Gutjuk’s relationship. Writing in Screen Daily after the film’s Berlin premiere, critic Wendy Ide noted:

The decision to equally foreground a white man’s story might lead to some criticism, particularly as that character’s actions and attitude seem as much informed by contemporary guilt and desire for reparation as they are by period accuracy.[2]Wendy Ide, ‘High Ground: Berlin Review’, Screen Daily, 24 February 2020, <https://www.screendaily.com/reviews/high-ground-berlin-review/5147533.article>, accessed 2 November 2020.

By returning to point-of-view shots through the rifle’s sight, the film reiterates one of its central themes: the power inherent within the gaze.

The prevailing attitudes of the day are more accurately represented in the seething prejudice of Travis’ adversary Eddy, especially when he bluntly tells Claire that they ‘can’t share this country’. The film’s most powerful evocation, though, is of this country itself, encompassing an array of spectacular locations in Kakadu National Park. Stylistically, the film works in an impressionistic mode. Its sound design is overwhelming; even its quiet moments are teeming with insects and animal life. Sound conveys the devastation of ballistic impact when moments of violence erupt, and the film regularly shows the curiosity of animals encountering the aftermath of deadly confrontations. Such moments emphasise the triviality of human foibles in the face of indifferent nature while simultaneously revealing the interconnectedness of all things, in a manner that recalls The Thin Red Line (Terrence Malick, 1998). The invocation of the Queensland-shot war film may not be totally incongruous, as the years separating Johnson’s High Ground from Yolngu Boy nearly equal Malick’s storied hiatus between Days of Heaven (1978) and The Thin Red Line.

Johnson’s earlier film dealt with cultural disconnection and rediscovery in contemporary times. High Ground shares these themes to an extent by exploring the attitudes and misunderstandings (well-intended and malevolent alike) that wrench the people from their land. At various times, its characters speculate aloud on the circumstances that have made them, and whether they might have led different lives under different ones. The films share key creative talent: screenwriter Chris Anastassiades; former casting director and now producer Maggie Miles; and Yothu Yindi members Marika and the late Dr M Yunupingu, who were cultural advisers for both films. But High Ground also reveals how much has changed in the last two decades of the Australian film industry. The film carries the badge of Bunya Productions and producer credits for that company’s David Jowsey and Greer Simpkin; in recent years, Bunya has forged an impressive track record in Indigenous film and television. Mystery Road has invested the police procedural with resonant postcolonial themes across two seasons on ABC TV, and it is hard to avoid comparing High Ground to Bunya’s recent Sweet Country (Warwick Thornton, 2017); Thornton’s and Johnson’s films each employ the iconography and narrative conventions of the western as a means of interrogating Australia’s violent past. More broadly in terms of recent Australian screen works, one is also reminded of The Nightingale (Jennifer Kent, 2018), which inflects similar themes with generic trappings: namely, the abject grotesquerie of Gothic horror.

Johnson’s reference points are present, but never overstated. As Travis and Gutjuk set out on their journey to find the wild man whose madness threatens to undermine the colonial project, the film invokes Apocalypse Now (Francis Ford Coppola, 1979)and its literary antecedent, Joseph Conrad’s 1899 novella Heart of Darkness – a link made explicit in High Ground with the appearance of a farmer named Kurtz (David Field). Johnson’s visual storytelling invests simple images with profound meaning: a powerful crocodile, bound, constrained and photographed; the unfinished, open-air church at the East Alligator River mission; a Bible slipped into a saddlebag on the way to a violent showdown; and a spearhead that changes hands, connoting the authority of law and the restoration of justice. So too do the film’s locations acquire meaning as the characters return to them, misunderstandings and miscommunications pile up, and cycles of violence and retribution recur. These moments of ugliness play out against a backdrop of awe-inspiring natural beauty.

In its collaborative mode of production, and in its adherence to multiple perspectives, High Ground is a film ingrained with a deep respect for the land and its cultures. It seeks to relitigate the senselessness of Australia’s frontier wars, while reminding us of the unmatched beauty of this country. It asks us to observe the same.

Endnotes

| 1 | See ‘Back on Track’, Australian Story, available at <https://www.abc.net.au/austory/back-on-track/10811402>, accessed 2 November 2020. |

|---|---|

| 2 | Wendy Ide, ‘High Ground: Berlin Review’, Screen Daily, 24 February 2020, <https://www.screendaily.com/reviews/high-ground-berlin-review/5147533.article>, accessed 2 November 2020. |