With The Nightingale (2018), her follow-up to the acclaimed The Babadook (2014), writer/director Jennifer Kent contributes to the ongoing cinematic process of reframing Australia’s closely held mythology around colonisation and nationhood as one rooted in a genocidal war of attrition. While the most recent, and stark, manifestation of this process was seen in Warwick Thornton’s Sweet Country (2017), we can also look to older examples such as John Hillcoat’s The Proposition (2005), Rolf de Heer’s The Tracker (2002), Fred Schepisi’s The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith (1978) and more. Yet, while The Nightingale does follow in the footsteps of these grim historical dramas, it is also, arguably, angrier and more ambitious. A relentlessly confronting and violent drama in the rape-revenge model, the film seeks not just to dramatise the inherently oppressive policies enacted by British invading forces during Australia’s colonial period, but to contextualise them as part of an ongoing campaign of subjugation against Indigenous peoples and other minorities – women, immigrants, those in subservient roles.

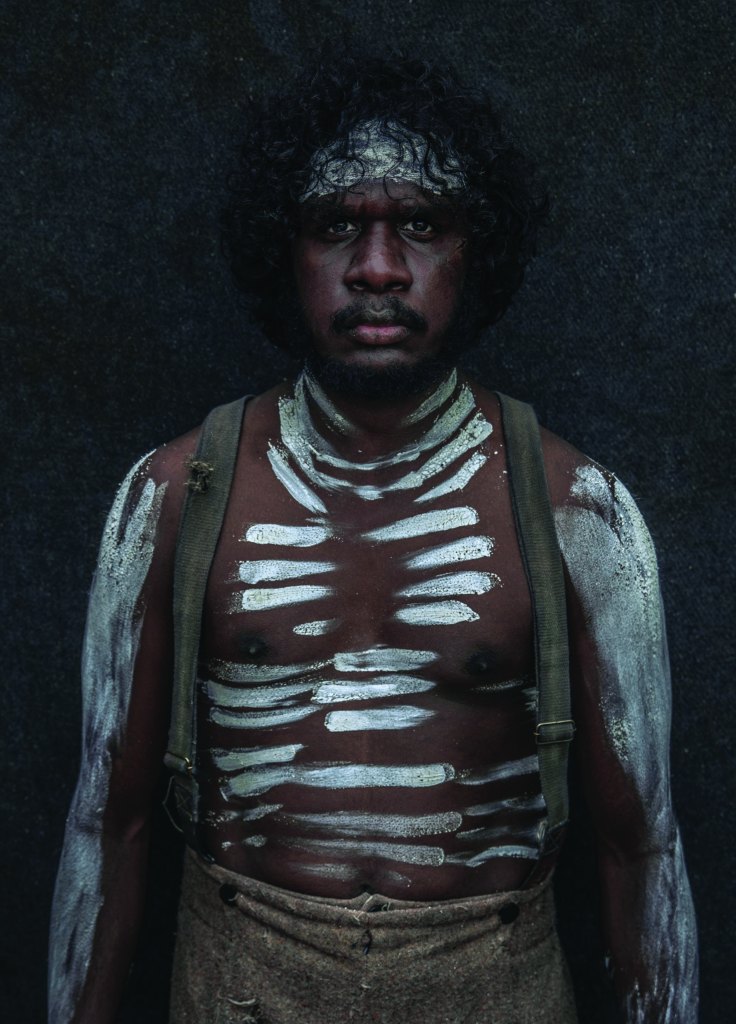

Set in 1820s Van Diemen’s Land (now Tasmania), The Nightingale tells the story of Irish convict Clare (Aisling Franciosi). Although married to freed convict Aidan (Michael Sheasby), with whom she has an infant daughter, she is kept in a state of effective sexual slavery by Lieutenant Hawkins (Sam Claflin), the officer in charge of the local garrison, who refuses to finalise her emancipation after she has finished her sentence. Frustrated after he is turned down for an expected promotion and angered after a drunk Aidan accosts him, Hawkins and his men rape Clare and viciously harm her family, before departing for a punishing overland trek to Launceston in a last-ditch attempt to appeal his promotion. Clare, bent on vengeance, takes Aidan’s horse and sets off in pursuit, enlisting the aid of a reluctant, belligerent Aboriginal tracker, Billy (Baykali Ganambarr). Their journey takes them into the heart of the ‘Black War’, a genocidal campaign against Indigenous Tasmanians.[1]See Greg Lehman, ‘Tasmanian Gothic: The Art of Australia’s Forgotten War’, Griffith Review, issue 39, 2013, pp. 193–204, available at <https://griffithreview.com/articles/tasmanian-gothic/>, accessed 3 June 2019.

The Nightingale is, shockingly and necessarily, even more brutal than it sounds on paper. In terms of graphic content, its tonal precursors are not the sweeping period dramas of yesteryear but deliberately provocative exploitation films – Meir Zarchi’s I Spit on Your Grave (1978), which follows a similar rape-revenge plotline, or Gaspar Noé’s Irreversible (2002), which counters what its director has viewed as a cavalier attitude towards sexual violence in mainstream cinema by presenting a rape in as unflinching a manner as possible.[2]‘If you do a movie with a rape and don’t show it, you hide the point … the thing is that if you show it in a disgusting way, you help people to avoid that kind of situation.’ See Gaspar Noé, quoted in Geoffrey Macnab, ‘“The Rape Had to Be Disgusting to Be Useful”’, The Guardian, 2 August 2002, <https://www.theguardian.com/film/2002/aug/02/artsfeatures.festivals>, accessed 3 June 2019. Certainly, The Nightingale’s depictions of violence – sexual or otherwise – are just as horrifying as anything seen in these rather notorious earlier works. But the seriousness of purpose with which Kent approaches them brings to mind the literary works of Cormac McCarthy, whose novels such as 2006’s The Road (adapted into a 2009 film, directed by Hillcoat) and 1985’s Blood Meridian combine linguistic lyricism and thematic complexity with frequent, stunning instances of brutality.

The film seeks not just to dramatise the inherently oppressive policies enacted … during Australia’s colonial period, but to contextualise them as part of an ongoing campaign of subjugation against Indigenous peoples and other minorities – women, immigrants, those in subservient roles.

Kent’s film is as carefully constructed as any of McCarthy’s novels. The soundtrack is bereft of non-diegetic music, the director steadfastly refusing to cue our emotions with an intrusive score (though Jed Kurzel – who also scored Justin Kurzel’s 2011 Snowtown, Ridley Scott’s 2017 Alien: Covenant and more – is still credited as composer). Director of photography Radek Ladczuk, who also worked on The Babadook, eschews the widescreen vistas and painterly landscapes typical of historical epics, instead employing the Academy ratio to lock the narrative and its characters into a confining, claustrophobic frame. And, despite the tactile sense of authenticity with which Alex Holmes’ production design and Margot Wilson’s costumes imbue The Nightingale’s world, Kent frequently fills the screen with human faces – almost invariably contorted in fear, pain, anger and hate.

Most often, it’s Clare’s face that we are focused on, Franciosi skilfully conveying the character’s rage and agony through her expressions. These sentiments are both overwhelming and wholly understandable. Even before the deplorable events that function as The Nightingale’s inciting incidents, Clare is downtrodden and abused: she is forced to sing for the entertainment of visiting army officer Captain Goodwin (Ewen Leslie) and berated by another female servant of a slightly higher station. The latter may seem like a minor interaction, but the film is extremely interested in hierarchies of power, which, in this universe, are essentially hierarchies of cruelty and oppression. The scullery maid has almost no power, but what she does have she uses to abuse Clare. Similarly, the ambitious Hawkins is cowed by Goodwin, and visits his frustrations on his own men, most notably the venal Sergeant Ruse (Damon Herriman) and the reluctant but still culpable Jago (Harry Greenwood). The evils depicted in The Nightingale are not individual, even though they are carried out by individual characters. They are systemic, self-replicating and cyclical. This last point is driven home when Hawkins casually takes an orphaned convict boy under his wing, arming him with a pistol and indoctrinating him into the culture of violence and authority in which he is serving as an officer.

And yet, although she is raped, beaten and left for dead, Clare does not occupy the lowest possible rung in the world of The Nightingale. She is, after all, white; the plight of the local Indigenous people, foregrounded through the character of Billy, is infinitely worse. The war of extermination is presented to us in the most forthright of ways – black bodies strung from trees, captive Aboriginal men casually shot in the head by white guards, a native woman kept as a sex slave, an infant child left to presumably starve in the bush. Indigenous characters simply run when they see white men coming, knowing that their most likely fate is to be shot on the spot.

As the film progresses, our protagonist pair come to understand one another, finding not solace in each other’s stories of horror … but a kind of communion in their righteous and well-earned hatred of their common oppressor.

Clare is complicit in these racialised acts of cruelty, even treating Billy as barely human when they first meet; Billy responds with unconcealed hostility and scorn towards her. As the film progresses, our protagonist pair come to understand one another, finding not solace in each other’s stories of horror (during one sojourn, Billy recounts the massacre of his entire family), but a kind of communion in their righteous and well-earned hatred of their common oppressor. Kent cannily draws parallels between Billy’s and Clare’s experiences and heritages. In one scene, after being described as ‘English’ by her companion, Clare bristles and angrily declares herself Irish – a protest that calls to mind the centuries-long subjugation inflicted by the former group on the latter. In an earlier scene, Clare and Aidan speak Gaelic when they are in their own humble hut – linguistically demarcating themselves from the English-speaking military/settler class – while, throughout the film, Billy and the other Indigenous Tasmanians speak palawa kani.[3]Theresa Sainty, a staff member at the Tasmanian Aboriginal Centre’s Language Retrieval Program, describes palawa kani as a ‘composite language’ that ‘literally translates as “Tassie black fella talk”’; see Causeway Films, The Nightingale press kit, 2018, p. 20. These mirrored aspects of their respective cultures tie the pair together: beyond a history of conquest by (and subsequent hatred for) the English, they share a vibrant oral and musical tradition as well as a strong desire to live the same way as their forebears.

The pair also share a mystical and spiritual dimension. Billy speaks of his totem, Mangana (the blackbird), aligning himself with its freedom and strength. For her part, Clare has nightly visions of her husband and child, which turn nightmarish as she begins enacting her vengeance. And in a particularly powerful parallel – and opposition – Clare and Billy are interwoven through avian designations. Clare’s singing makes her valuable to the officers: she is the ‘nightingale’ of the title (a nickname given her by Hawkins), a captive songbird. Billy, on the other hand, is a pest to be exterminated: his acts of identification with his bird totem, dancing to and singing the song of the Mangana, are initially presented as barbaric and strange. Gradually, however, we are invited to connect the two, and to see them as essentially similar in their oppression and Othering.

While it is clearly modelled on the revenge-thriller formula, The Nightingale refuses to endorse violence – not even the violence that Clare inflicts on her tormentors. Catharsis is steadfastly withheld. In fact, when Clare is first able to attack and murder one of the soldiers, her victim is the remorseful Jago, whom she stabs to death in an excruciatingly drawn out and sickening sequence. As viewers, we are primed by Clare’s grim journey into the wilderness, by her dogged determination to see justice done, to feel some kind of victory when she takes down her first victim. Instead, we are utterly horrified.

This carefully calibrated response speaks to Kent’s intentions and craft. In her director’s statement, the filmmaker notes:

I wanted to tell a story about violence. In particular, the fallout of violence from a feminine perspective. To do this I’ve reached back into my own country’s history. The colonization of Australia was a time of inherent violence[:] towards Aboriginal people, towards women, and towards the land itself, which was wrenched from its first inhabitants. Colonization by nature is a brutal act.[4]Jennifer Kent, ‘Director’s Statement’, in Causeway Films, ibid., p. 4.

Although it is set in a specific time and place in Australian history, The Nightingale functions as an indictment of all forms of colonialism, all forms of oppression and, ultimately, violence itself. While Kent’s positioning of Clare at the centre of the narrative already emphasises female agency, its rape-revenge arc also – much like that in other rape-revenge works from this country – interrogates Australia’s valorisation of the ‘wild colonial boys’ mythology and macho assertions of power.[5]See Alexandra Heller-Nicholas, ‘Fair Games and Wasted Youth: Twenty-five Years of Australian Rape-revenge Film (1986–2011)’, Metro, no. 170, Spring 2011, pp. 86–7. Moreover, the film’s colonially themed precursors in Australian cinema, although frequently dealing with similar topics and coming from a similar political and cultural angle, nonetheless indulge in the catharsis of righteous retribution – recall: Sam Kelly (Hamilton Morris) slaying the rapist Harry March (Leslie) in Sweet Country, Jimmie Blacksmith (Tom E Lewis) taking vengeful retribution against his oppressors in The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith, or the biblical fratricide of The Proposition. By contrast, while The Nightingale goes to extreme lengths to detail the horrors endured by its protagonists, thereby leaving us in no doubt about the motivations fuelling their rage, its refusal to excuse their own violent actions means they are held accountable in a way that few other works have had the courage to do. If, as the film frequently illustrates, the violence is systemic, then all who participate in the system are culpable.

Which means that, by the film’s own moral system, there can be no happy ending for The Nightingale; to indulge in such would be counter to all that has gone before. In fact, Kent goes so far as to toy with the notion of anticlimax. While Hawkins is killed by Billy, who eventually learns that his entire tribe has been eradicated by the English, we know by this point that such an act does not bring an end to the cycle of oppression; indeed, the inequalities our society is faced with almost 200 years later crystallise the reverberating effects of not just the soldiers’ aggression, but also Billy’s and Clare’s quests for revenge. ‘[T]he arrogance that drives [colonisation] lives on in the modern world,’ Kent reflects. ‘For this reason, I consider this a current story despite [it] being set in the past.’[6]Kent, op. cit., p. 4.

The Nightingale ends abruptly. Having fled Launceston after the killing of Hawkins, with Billy seemingly mortally wounded, the pair watch the sun rise over the ocean. Billy’s injury aside, we’re given very few indications as to what will come next – there is no sense of conclusion, no denouement, and certainly no genre- or period-appropriate ride into the sunset. Given our knowledge of the ultimate futility of all that has preceded this scene, there seems to be no other possible conclusion than simply ceasing the telling of this string of horrific events – which is exactly what the film does, suddenly cutting to the credits with no fanfare. It’s as if, by modelling, the film invites us, too, to sever our connection to the cycle of power and violence of which we are part; instead of grappling for the next rung in the hierarchy, we must seek to step off it.

This ending is a brave choice, and The Nightingale is a brave film. Following on from the success of her horror film debut, it would have come as no surprise if Kent had continued in a similar vein and genre. Instead, she has delivered a work of uncommon ambition and thematic scope – one that doesn’t turn away from shocking and potentially alienating its audience in service to its own unshakable moral compass.

Endnotes

| 1 | See Greg Lehman, ‘Tasmanian Gothic: The Art of Australia’s Forgotten War’, Griffith Review, issue 39, 2013, pp. 193–204, available at <https://griffithreview.com/articles/tasmanian-gothic/>, accessed 3 June 2019. |

|---|---|

| 2 | ‘If you do a movie with a rape and don’t show it, you hide the point … the thing is that if you show it in a disgusting way, you help people to avoid that kind of situation.’ See Gaspar Noé, quoted in Geoffrey Macnab, ‘“The Rape Had to Be Disgusting to Be Useful”’, The Guardian, 2 August 2002, <https://www.theguardian.com/film/2002/aug/02/artsfeatures.festivals>, accessed 3 June 2019. |

| 3 | Theresa Sainty, a staff member at the Tasmanian Aboriginal Centre’s Language Retrieval Program, describes palawa kani as a ‘composite language’ that ‘literally translates as “Tassie black fella talk”’; see Causeway Films, The Nightingale press kit, 2018, p. 20. |

| 4 | Jennifer Kent, ‘Director’s Statement’, in Causeway Films, ibid., p. 4. |

| 5 | See Alexandra Heller-Nicholas, ‘Fair Games and Wasted Youth: Twenty-five Years of Australian Rape-revenge Film (1986–2011)’, Metro, no. 170, Spring 2011, pp. 86–7. |

| 6 | Kent, op. cit., p. 4. |